By Dr Mary Lavelle and Dr Trisha Forbes

Restrictive practices in mental health inpatient care, as defined by the Mental Health Act 1983, – physical restraint (holding to prevent movement), seclusion in a locked room, and rapid tranquilisation – are among the most intrusive interventions used in healthcare. They are intended to keep people safe in high-risk situations, but their impacts are far-reaching and often harmful.

As highlighted by the Royal College of Nursing, in England, over 100,000 people are admitted to acute mental health wards every year, with 50–60% detained under the Mental Health Act due to severe psychiatric symptoms such as psychosis and high risk of harm. Northern Ireland does not publish comparable figures, but we have no reason to think rates differ substantially. In England alone, some 60,000 incidents of restraint occur annually – around six every hour.

The consequences are serious: people report trauma, fear, disempowerment, and dehumanisation; staff may suffer injuries, anxiety, and burnout, worsening retention. Restrictive practices are estimated to cost the UK £69 million annually, and in rare cases, physical restraint has resulted in fatalities.

The Policy Context in Northern Ireland

The Regional Policy on the Use of Restrictive Practices in Northern Ireland sets a clear expectation: these interventions must be minimised, used only as a last resort, proportionate, and compliant with human rights standards. The challenge is ensuring that these principles are realised consistently on the ward floor – especially in the context of high bed occupancy, staff shortages, and the increasing complexity of patient presentations.

Learning from the Communication and Restraint Reduction (CaRR) Study

We have recently conducted research on mental health wards in England, examining staff communication and ward approaches to restraint reduction in practice. The key message from the research is that compassionate, relational care that promotes service user agency, is the most effective way to prevent and defuse potential conflict and avoid restrictive interventions.

The study also found that embedding strategies to prevent and learn from incidents were also effective. However, in reality, staff often struggled to sustain these approaches. High workloads, administrative demands, perceived organisational priorities frequently pulled staff away from direct engagement with patients – the very thing that helps prevent incidents in the first place.

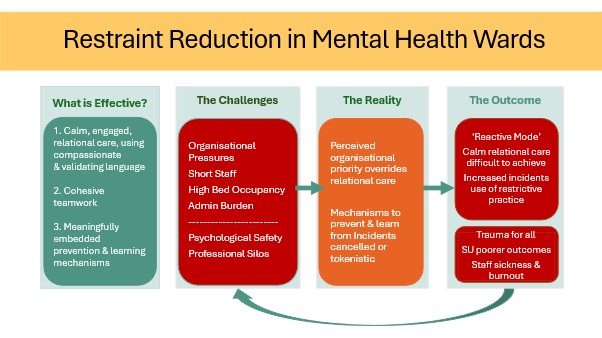

The implication is clear: reducing restrictive practices requires that organisational priorities and resources are aligned with compassionate, relational care. This alignment must be reinforced by compassionate leadership and a culture of psychological safety. Without these foundations, even the most dedicated and skilled staff are compelled to respond reactively rather than proactively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Summary of CaRR Study Findings in England

Why This Matters for Northern Ireland These findings resonate with the challenges we know exist in Northern Ireland. Our mental health wards face similar pressures to those in England: high patient turnover, staffing shortages, and frequent exposure to aggression and distress. While Northern Ireland’s Regional Policy provides a strong framework, turning it into everyday reality means addressing both the way staff interact with patients in high-risk moments and the organisational systems that support or constrain best practice.

The Communication and Restraint Reduction (CaRR) study in Northern Ireland

To build the evidence base for our own context, we are launching a Northern Ireland–based study that will examine de-escalation and restraint reduction on inpatient wards in HSC Trusts.

Specifically, the study will examine how staff prevent, respond to and learn from incidents of conflict and distress on inpatient wards in Northern Ireland. Our findings will provide regional evidence directly informing training, practice and policy.

Looking Ahead

Restrictive practices may never be eliminated entirely, but they can – and should – be rare, last-resort measures. Northern Ireland now has the opportunity to take an evidence-based approach, grounded in our own services, to significantly reduce their use.

Our upcoming study will not only measure what’s happening on our wards – it will explore how policy, organisational systems, and frontline practice can work together to create safer, more humane environments for both patients and staff.

The goal is straightforward but urgent: to ensure that every person in our mental health services is treated with dignity, compassion, and the least restriction necessary.

For further information regarding the CaRR Study please contact Mary Lavelle at Queen’s University Belfast.

About the Authors

Dr Mary Lavelle is a chartered Psychologist in the British Psychological Society and Senior Lecturer in the School of Psychology at Queen’s University Belfast. Mary completed her PhD at Queen Mary, University of London in 2012, where she employed 3D motion capture techniques to investigate social deficits in psychosis. From here, she held Research Fellow positions in King’s College London, Imperial College London.

Dr Trisha Forbes is a Research Fellow in the School of Psychology at Queen’s University Belfast. Trisha completed her PhD at Queen’s in 2018, which was a qualitative inquiry exploring young peoples’ perceptions of suicide in an area outside West Belfast, and their feelings of connectedness to the community. Trisha’s research interests are in mental health, the link between mental health and the arts, and how things may be improved for service users.

Leave a Reply