By KEITH CAVERS

Two interesting points arise from a closer examination of Richard Newton’s caricature of Parisot. It would be natural to take at face value the engraved titling of this print:

Mademoiselle Parisot

Sketched at the Opera by Rd Newton

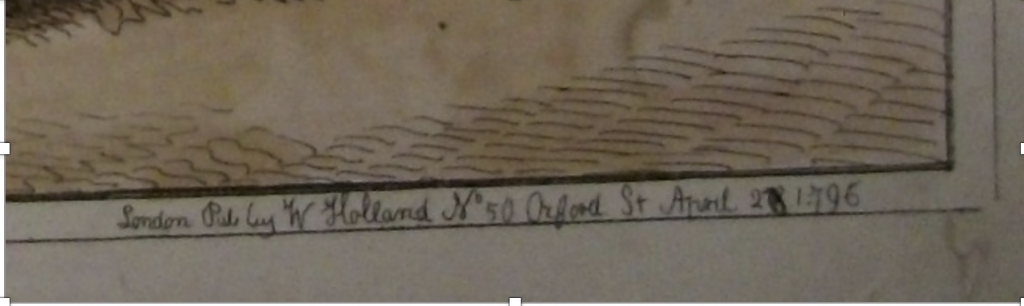

London Pub. by W Holland No. 50 Oxford St.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/48485001.

The impression in the British Museum adds the year 1796 but if you look closely (and you can!) you will see that the date is added in manuscript – though there is the ghost of an engraved date which certainly ends in a “6”. In the impression held in the Theatre Collection at Harvard the full date survives – “ … April 28 1796” though the “8” has been overwritten in ink to show an “0”. This is all very strange but if we apply George Chaffee’s dictum “Always read the image” I think we can explain away the anomaly in the engraved date.

If we look at the image – what do we see – we see Mlle Parisot dancing with two figures in the stage box but who are they? Well the British Museum impression, again in manuscript has the addition of “D. of Queensbury” and we might expect to see him as he appeared, and appeared readily identified, in a previous print which bears the titling “A Peep at the Parisot! with Q in the Corner!/ I Cruikshank / London Pub May 7 1796 by S.W. Fores No. 50 Piccadilly.” In that print he is also using a Dollond monocular to look up the dancer’s skirt. The second occupant of the box who is also observing the dancer through a glass is also readily identifiable – it is Shute Barrington (1734-1826), Prince Bishop of Durham – he whose intervention in a Lord’s debate on Divorce brought down a cascade of caricatures when he attacked French Opera Dancers

who by their allurement of the most indecent attitudes, and most wanton theatrical exhibitions, corrupted the people.

The Parliamentary Register, vol. 5 (London: J. Debrett, 1798). Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

The problem arises when we find that the noble prelate made his speech on 2nd March 1798, two years after the supposed engraving of the print!

I think that the solution is that Newton’s print was engraved in 1798 and fraudulently dated 1796 to match the Cruickshank caricature – subsequently the erroneous date was erased from the plate and in the case of the British Museum impression someone who knew of the existence of the earlier date simply attempted to restore it. It makes every pictorial sense that this print belongs with those of the well documented 1798 costume controversy.1

The Royal Collection contains a drawing which has been catalogued thus:

Mademoiselle Parisot, a ballet dancer, is watched by 2 old men, Duke of Queensbury and Barrington, Bishop of Durham (?). Copy of the print BM Sat. 8893.

I’m afraid I have not seen this drawing ‘live’ but (again through excellent internet access) I think that this is undoubtedly the original drawing by Newton for the print and not a copy made from it. It would make no sense to shift the figure in making a copy of the print and in any case the drawing is clearly very superior to the subsequent engraving and a most charming (and presumably more accurate) portrait of this dancer.

A Harvard impression gives “Oxford St April 20th [or 28th ] 1796″ which has been removed in the British Museum impression – I suspect that it was published in 1798 with a false date – hence its removal from the plate – why? Goodness knows.

Notes

- Rauser, Amelia. 2020. The Age of Undress: Arts, Fashion, and the Classical Ideal in the 1790s. Yale University Press, pp. 84-85. Editor’s note: This source betrays the conflation of events relating to Mlle Parisot in 1796 and 1798 as observed above by Cavers.

Next post

‘Portraits of Mlle Parisot’ by Sarah McCleave will appear on 27 February.