By SARAH McCLEAVE

The tale of Mlle Parisot’s London reception holds two further images to consider. The featured image is a portrait drawn by Arthur William Devis (1762-1822). Depicting her in the guise of Hebe, goddess of Youth, it is a tribute to Parisot’s grace and elegance; although the beauty of her figure is evident, the painter appears to celebrate rather than exploit the dancer. A contemporary report, however, could not refrain from alluding to Parisot’s disreputable entourage:

Devis is engaged upon a Portrait of the beautiful PARISOT. It is to be a whole length, and there is already an active competition between old Q. [Lord Queensbury] and Lord G[rosvenor] who shall be the happy possessor.

True Briton, 10 June 1796

The nudge and wink of the newspaper notice may also point to a scheme to finance the portrait, which as a full-length image would normally be commissioned by a funder with deep pockets. Is it likely that an auction was intended to sell the original image? We can safely assume that Parisot herself did not commission it: her salary at 300 guineas per annum would not stretch to such luxuries and she was also reputedly supporting her mother and sister in France.1) And yet we can understand why she might want to encourage such an enterprise: Gillray’s satirical print of May 1796 – in which she appears as a saucy nymph encouraging the attentions of the married Didelot – would have been very damaging to her personal reputation. A serious portrait and its subsequent engravings could promote her on more flattering terms. For Devis, an artist who has recently returned from India, this project may have been imagined as a means to establish himself in a crowded London market. The connection to engraver and publisher John Raphael Smith (1751-1812) would have been particularly welcome, for the older artist was highly regarded in his trade, with a very successful publishing business. While Smith’s role implies an anticipation that the engravings of this prominent stage performer would sell well, finding a buyer for the original portrait would have been a bit of a gamble: the nearest precedent we have in the London art market of the period is the 1782 full-length portrait of Giovanna Baccelli by Thomas Gainsborough — but Baccelli was at that time living with John Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset, who commissioned or paid for at least two further portraits and a sculpture of that dancer during the course of their relationship. Parisot, according to the press of her day, stoutly discouraged the attentions of her elderly admirers so they lacked a lover’s genuine interest in commissioning the portrait. Grosvenor was in fact an avid art collector, but a surviving catalogue of his collection does not list any images of Parisot.2) Queensbury was better known for his interest in women and horses, and the extent of his art collection (if any) is currently unknown.

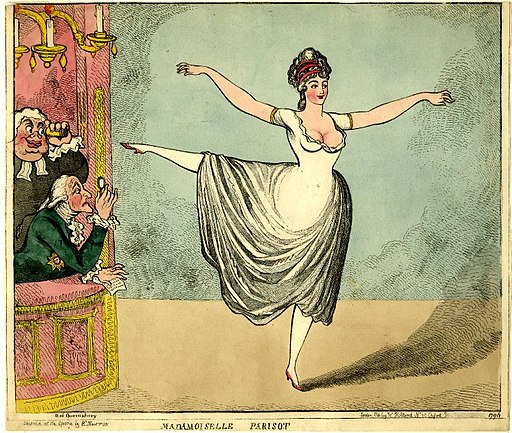

The racier image above, drawn by John James Masquerier, is a curious affair. According to the National Portrait Gallery, “John Masquerier was an accomplished portraitist who enjoyed a wide practice among the intellectual and artistic communities at the turn of the nineteenth century.” The bare bosom seems a direct reference to Parisot’s stage costumes rather than an inevitable feature of Masquerier’s style. (For comparison see his more respectful portraits of Emma, Lady Hamilton, or the actress/singer Rosoman Mountain, née Wilkinson.) Parisot’s bared teeth further suggests an intended salaciousness; it is difficult to credit that she would have willingly posed in this manner. Indeed, the portrait does not demonstrate the level of finish we find in the studio works by Masquerier, and it is plausible to speculate that he took a sketch of Parisot at the theatre, and when committing it to paint freely assigned a costume and facial expression that would maximise its commercial appeal amongst a certain clientele.

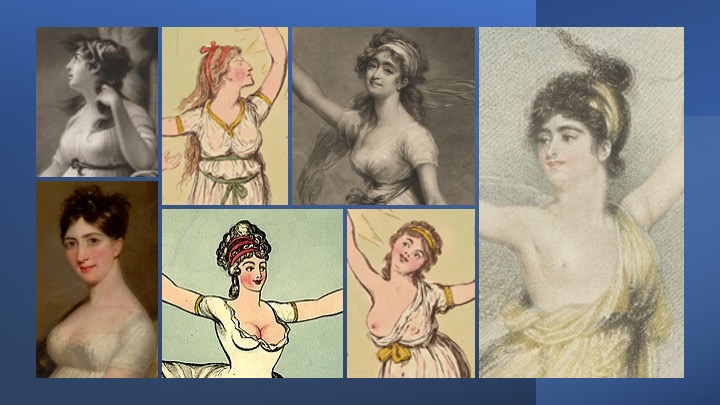

Parisot’s exploitation (this is a more apt word than ‘promotion’) in the visual arts is aptly conveyed by the image below, which conveys details of the bust portion of caricatures and portraits of herself and other female contemporaries as discussed in the blogs on this dancer. The Devis portrait suggests her artistic legacy; the remaining images tell us something of the times in which she lived.

- For Parisot’s salary, see the True Briton [1793], 21 Mar. 1796; for her family situation, see “News.” Oracle, 18 Aug. 1796. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, Gale. Accessed 21 Sept. 2021.

2. Westminster, R. Grosvenor., Young, J. (1820). A catalogue of the pictures at Grosvenor house, London: with etchings from the whole collection. London: Pub. by the proprietor.

Images

Devis, Arthur William (artist) and John Smith (engraver). 1797. “Mdlle. Parisot.” London. Harry Beard Collection, Victoria & Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1153387/h-beard-print-collection-print-devis-arthur-william/. Accessed 21 April 2021.

Masquerier, John James (artist) and Charles Turner (engraver). 1799. “Mademoiselle Parisot.” [London}: C. Turner. Harry Beard Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1153627/h-beard-print-collection-print-turner-charles/ Accessed 21 April 2021.

Next post

Emilie Bigottini will be the subject of the next post (March 2022).