By Sarah McCleave

Marie-Anne Cupis de Camargo (1710-1770) is acclaimed as a female dancer who took on the most challenging aspects of contemporary dance technique, displaying a capacity to render jumps, entrechats (jumps with crossed feet), turns and beaten steps at a level normally confined to her male peers. Initially trained by her father in her native city of Brussels, the support of the Princesse de Ligne took Camargo to Paris where she studied under the famous Françoise Prévost. Father and daughter assumed a joint appointment at the theatre in Rouen before returning to the Paris Opéra in 1726 where Marie-Anne enjoyed a glittering career spanning 25 years – interrupted by a six-year sabbatical (1734/5-1740) at the behest of her then lover Louis de Bourbon, Comte de Clermont. Camargo rounded off her career with engagements at each of London’s patent theatres, dancing at Drury Lane theatre during the 1750-51 season and at Covent Garden theatre for the following two seasons.

It would be easy to fill several blogs with tales from Camargo’s colourful private life, but this would be to overshadow her considerable professional achievements.1 Of the anecdotes surrounding her, that of an early triumph at the Paris Opéra is worth repeating because it encapsulates the traits for which she became famed as a performer. The event occurred when she was a young dancer, and had been relegated to the corps de ballet notwithstanding a highly successful début on 5 May 1726. Camargo saw an opportunity when David Dumoulin missed his entry for a solo as a demon. According to the musicologist and critic François-Henri-Joseph Blaze (1784-1857):

Mademoiselle de Camargo, with a sudden inspiration that animated her, quit her rank, and launched herself into the middle of the theatre where she improvised the steps of Dumoulin, dancing with verve and with fancy, carried away by the admiration and enthusiasm of the spectators.2

Castil-Blaze, La Danse et les Ballets depuis Bacchus jusqu’à Mademoiselle Taglioni, p. 193.

Unlike her contemporary Marie Sallé, Camargo’s name seems to have resurfaced repeatedly after her retirement: she was the inspiration (title-role) for a number of comic operas or ballets in both France and Italy3; the naming of the Camargo society – an organisation founded in 1930 to foster British ballet – demonstrates that her legend resonated some 150 years after her death. This blog will consider Camargo’s fame as evidenced in portraiture.

The best known image of Camargo is the 1731 portrait drawn by Nicolas Lancret; it conveys some of the lightness and elevation of her dance style. By placing the dancer in a fête champêtre, Lancret draws on the pastoral associations of the locale and its attendant musician-shepherds to frame Camargo as that most available and willing of mythological females, the nymph. But Lafaye’s verses beneath the painting bring us back to Camargo the professional4: they are written in the first person, giving the dancer agency to claim her own originality and a technique matching that of two illustrious male dancers of the day, Jean Balon (1676-1739) and Michel Blondy (1676-1739).

Fidele au loix de la cadence

Je forme, au gre de l’art, les pas le plus hardis

Originale dans ma danse

Je peux le disputer aux Balons, aux Blondis.

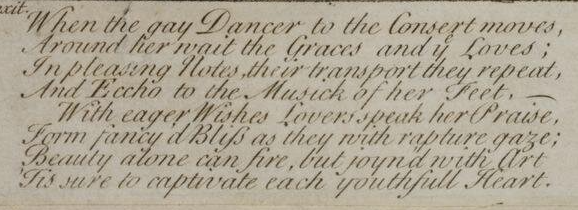

Lancret’s genre painting was engraved by at least four artists. The original issue was engraved by Laurent Cars and published in Paris.5 Garnier subsequently engraved a reversed image for London-based fraternal publishers Thomas Bowles II (c.1695-1767) and John Bowles (1701?-1779). This image included the original verse in French as well as a new poem in English.

The British Museum holds an exemplar of the Lancret (dated between 1730 and 1743) where the engraver and also the publisher chose to remain anonymous; this is thought to have been produced without consent during Lancret’s lifetime, and was the subject of a lawsuit.6 Francis Vivares (1709-1780) also engraved Lancret’s genre painting of Camargo for publication in London; the British Museum describes him as “one of the main links between the French and British print trades”.7 The British Museum dates this particular engraving (no image is available) very broadly between 1730 and 1780, noting that it is “reduced” from the Cars. Also reproduced is part of the verse, which is either a translation of a close paraphrase from LaFaye’s lines for the Lancret: “An original in my dance… The boldest steps wth. justice trip the ground.”8 It seems likely that the print would have been published during Camargo’s tenure as a dancer at the two patent theatres in London (so between September 1750 and May 1753), but this is conjecture.

Camargo was the subject of a half-portrait drawn by Jean Marc Nattier ( 1685-1766); this was subsequently “Printed in Paris, Published by Manzi, Joyant & Co.” The New York Public Library assigns this print a tentative date between 1890-1899; the biographical note for Manzi-Joyant supplied by the British Museum could suggest a date of 1907 or later, as the firm prior to that date was known as Jean Boussod, Manzi, Joyant & Cie. If so, this print of a dancer last active in 1753 was judged a commercial proposition for a printer to issue under Camargo’s name some 250 years after her retirement.

Nearly 50 years after her death, Camargo became the subject of a hand-coloured engraving, depicting her mid-step with her right arm raised. Drawn by Louis-Marie Lanté (1789-1871), it was engraved by Robert William Smart (1792-c.1832) and published by the London-based firm S. & J. Fuller on 1 April 1829. Lanté is best known as “the most prolific designer of the famous Journal des Dames et des Modes for which he drew fashion figures in watercolor”; he exhibited at the Paris Salons between 1824 and 1838.9 Another copy of this image, engraved by Georges Jacques Gatine (1773-after 1841) and bearing the title ‘La Camargo 1760’, is coloured differently although the pose of the dancer and the costume (apart from the colour) are identical. The Victoria and Albert Museum give the publication date of this print as “first half 19th century”.10

Such was her sustained celebrity that the famous Lancret fête champêtre was engraved afresh (in reverse, as a reduction) in the late nineteenth century by Edmond Hédouin (1820-1889); Gallica gives 1880, or 110 years after the dancer’s death, as its publication date. Lancret had also drawn a half-length portrait which would later be engraved by Eugène Gervais (1846-1880) and published in 1865. Both these posthumous prints bear the name of their subject, which suggests that Camargo remained a vivid cultural memory who could still intrigue and interest the public long after her death.

References

- Readers looking for a lively and imaginative account of Camargo’s life and times can easily acquire a modern reprint of Gabriel Letainturier-Frandin’s 1908 bo0k on this dancer, which amplifies some verifiable benchmarks and relationships in the dancer’s career with a wealth of imagined scenarios — complete with dialogue. For a reliable biography see Régine Astier (1998), ‘Camargo, Marie’ in International Encyclopedia of Dance, edited by Selma Jeanne Cohen et al, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2. “Mademoiselle de Camargo, qu’une inspiration soudaine vint animer, quitte son rang, s’élance au milieu du théâtre, improvise le pas de Dumoulin, danse de verve et de caprice, et transporte d’admiration et d’enthousiasme les spectateurs.” Castile-Blaze (1832). La Danse et les ballets depuis Bacchus jusqu’à Mademoiselle Taglioni, reprinted by Hardpress, 2019.

3. Theatre works inspired by Camargo include: La Camargo choreographed by Ippolito Montplaisir (Milan, 1868; revived Venice 1871; Turin 1871); Charles LeCoq’s La Camargo, opéra comique text by A. Vanloo et E. Leterrier (Paris, 1879); La Camargo ballet pantomime written by Judith Gautier and Armand Tonnery (Paris, 1893). The Archives Nationales (Paris) in a folder labelled “Manuscrits de livrets refusés, 1830-1863” (pressmark AJ/13/199) includes the rejected script for “la Camargo / ballet pantomime / en/ Deux actes / et cinq tableaux / par/ André de Bussy.”

4. The author of the verse is identifed by Voltaire in a letter to Nicolas-Claude Thieriot dated 14 April 1732. See Lettre 462, Voltaire’s Correspondence, edited by Theodore Besterman (1953). Geneva: Institute et Musée Voltaire. vol. 2, pp. 299-301.

5. Henry Bromley’s A Catalogue of Engraved British Portraits lists the Cars engraving and also an unspecified image by G. Bickham. Bromley does not clarify whether this attribution was to the engraver George Bickham the elder (1684–1758) or the print-maker and publisher George Bickham the Younger (c. 1706-1771). Bromley, Henry [1793]. A catalogue of engraved British portraits, from Egbert the Great to the present time. Consisting of the effigies of persons in every walk of human life; as well those whose services to their country are recorded in the annals of the English history, as others whose eccentricity of character rendered them conspicuous in their day. With an appendix, containing the portraits of such foreigners as either by alliance with the Royal Families of, or residence as visitors in this Kingdom, or by deriving from it some title of distinction, may claim a place in the British series Methodically disposed in Classes, and interspersed with a number of Notices Biographical and Genealogical, never before published. By Henry Bromley. Printed for T. Payne, Mews Gate; J. Edwards, Pall-Mall; W. Otridge and Son, Strand; and R. Faulder, New Bond Street, MDCCXCIII. [1793], p. 432. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, accessed 9 Dec. 2022.

6. See Part 4 of Emmanuel Bocher (1877). Les Gravures françaises du XVIIIe siècle, ou Catalogue raisonné des estampes, eaux-fortes, pièces en couleur, au bistre et au lavis, de 1700 à 1800, as cited by the British Museum: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1882-0812-1, accessed 12 December 2022.

7. See https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG49900, accessed 9 December 2022.

8. See https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_K-58-92, accessed 9 December 2022.

9. Wolfs Gallery, https://wolfsgallery.com/artists/louis-marie-lante, accessed 9 December 2022.

10. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O102905/la-camargo-1760-print-lant%C3%A9-louis-marie/la-camargo-1760-print-lant%C3%A9-louis-marie/?carousel-image=2006AE5399, accessed 9 December 2022. The biographical note for Georges Jacques Gatine by the British Museum gives his life dates as ‘1773-1841 after’, describing him as “Engraver and etcher, specialist in costume plates, mostly after Lanté.”

Next post

The next post will consider portraits of the dancer Marie Sallé (1709-1756).