Lola Montez stimulated a considerable posthumous cultural legacy, remaining a subject of interest in places where she’d lived and performed (including Germany, France, USA, Australia) – but also in places she’d never been. This blog post will highlight a small selection of the works in various media inspired by this controversial performing artist.

Coverage of Montez in the press throughout the 1860s remained fairly intense. The London-based weekly, the Era, had by the time of Montez’s death become a regular source of information on all matters theatrical. Its two-column obituary of Montez (10 February 1861), reproduced from the New York Herald of 21st January demonstrates the range of response that Lola inspired. This obituary was swift to point out her personal faults (“Lola … managed to quarrel with everybody she met”), and to dismiss her skills as a performer (“As an artist she was good for nothing.”). Her début at New York’s Broadway theatre took place “to a crowded house, nearly all men. Everybody was disappointed in her dancing and appearance.” Such was the culture of the time that even Montez’s thinness was cast as a moral issue, a product of her “fast living and incessant smoking”. The Herald/Era is most positive when discussing Lola’s career as a lecturer, as she “attracted large audiences, her manner being very prepossessing, and her delivery excellent.” It also recognized that “Lola was very generous to people about her, and would share her last meal with a friend.” Indeed, at her untimely death Lola was surrounded by friends who “cared for her, and mourned her loss”.1)

Montez had the perfect combination of qualities to sustain her celebrity status: some sympathetic attributes, some marked personal flaws, and a tremendous charisma combined with enough capacity as an entertainer to make herself known in the public sphere. By the end of the decade, she was remembered in a nostalgic manner by Paris’s Le petit Figaro, which in its gossip column (“Causeries”) of 22 June 1869 cast her as “une pauvre errante” (a poor erring one) and the leading player in a piece on actresses who’d managed affairs with royalty. In reviewing her Paris years, it suggested Lola’s engagement as a dancer at the Porte de Saint-Martin was secondary to the negative role that she, as a beautiful woman, was obliged to assume — of selling her charms (“Elle … vendu ses charmes au plus offrant … pour en venir jouer un de ces rôles negatifs dans nos théâtres. Singularité de la vie des belles.”) Of her Bavarian sojourn and subsequent exile, the paper tartly observed that to keep a single, defenceless woman out of the region the garrison’s forces at Munich were doubled.2) And so Le petit Figaro mentions Lola’s capacity to wreak havoc while poking fun at authority for its overblown response to her. In effect, the Parisian press (as did the Anglo-American) traded in on Montez’s fabulous life to generate material, but did not feel so obliged to adopt the moral high ground. As for the Antipodean press, the name of Lola Montez generated the most coverage during her decade as a traveling dancer (the 1850s, some 1000 references), with a similar level of exposure in the decade of her death.3)

As was the case in her life, so it was in death: any purportedly biographical publication about Mme Montez was assuredly a blend of the fictional and of her equally fabulous reality. The tone of the publications reflected the nature of the society in which they were generated — and the role Lola played within that milieu. And so in Germany during or shortly after her Munich period a study of her relationship with the Jesuits, and also of her political significance, came out in print.4) In America – where as a fervent Christian Lola spent her final months in relative seclusion and sobriety – within six years of her death the Protestant Episcopal Society for the Promotion of Evangelical Knowledge had published The Story of a Penitent: Lola Montez. By the early 20th century her persona as an adventuress held a particular appeal in the Anglophone world — as her place within William Rutherford Hayes’s 1908 biographical compilation Seven Splendid Sinners suggests.

Lola has also stimulated a considerable number of creative works in a range of media. Novels, films, a musical, and songs dating into the second decade of the 21st century demonstrate her abiding capacity to generate interest. Some of these works draw on her actual adventures; others create entirely fictional episodes that use the name of Lola Montez to represent an uninhibited adventuress.5)

Sometimes one work might spawn another in a different medium. In 1918 Robert Heymann (1879-1946) adapted and directed a silent film “Lola Montes” on a novel by Adolf Paul (1863-1943), with Leopoldine Konstantin (1886-1965) in the title role. Paul’s novel also led to further Lola-inspired films including The Palace of Pleasure (1926; directed by James Flynn) and Lola Montez: One mad kiss (1930, directed by Marcel Silver and James Tinling). Max Ophuls’s final film, Lola Montès of 1955 is described on YouTube as “a magnificent romantic melodrama, a meditation on the lurid fascination with celebrity, and a one-of-a-kind movie spectacle” (criterioncollection). The trailer gives us a wonderful glimpse of incidents many of which would not have had to rely on fiction, although Lola’s stint as a circus performer in the film was imagined rather than quasi-biographical. Indeed, ‘The Circus’ has become the title for a suite of music by Georges Auric from the film.

A 1958 musical with music by composer Peter Stannard and lyrics by Peter Benjamin was broadcast on Australian television in 1965, with a particular hit in the song ‘Saturday Girl‘; a CD was released in 2000, with a one-off 60th anniversary production in 2018 by David Spicer. Lola has also inspired the occasional popular song from musicians working in markedly different styles — including the ‘Latin Folk Exotica’ of Elisabeth Waldo’s 1969 ‘The Ballad of Lola Montez‘ on her Viva California album and the groove metal number ‘Lola Montez‘ on Volbeat’s 2013 album Outlaw Gentlemen and Shady Ladies (Universal). In 2017, an acoustic folk concoction ‘The Countess Lola Montez’ was written and performed by Norman and Nancy Blake on Brushwood Songs and Stories (Plectrafone Records).

Lola Montez has attracted and sustained this attention due to her unconventional personal life and behaviour; her characteristic audacity and flair would also have lent sparkle to her performances on stage. The compelling stories surrounding this difficult but fascinating woman have created and sustained her celebrity for over 150 years.

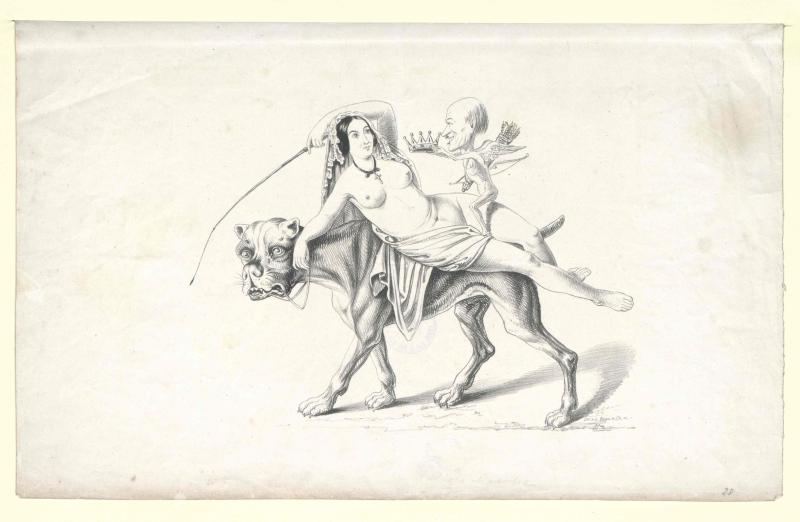

Featured Image

A naked Lola Montez dominating the dwarfed King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Artist not identified. Austrian National Library, Austria – Public Domain. Europeana.

References

- Gale News Vault, accessed 22 September 2023.

- “Pour empêcher une pauvre femme, jeune, rieuse, et sans défense de pénétrer dans Munich, on doubla le garnison …”. Théodore de Grave, 1869, “Causeries”, in Le petit Figaro, 22 June. Retronews, https://www.retronews.fr/, accessed 23 September 2023.

- Trove, https://trove.nla.gov.au/, accessed 21 September 2023. Not all of these references are to the dancer, as a schooner named for her accounts for a significant portion of these figures.

- Paul Erdmann, 1847, Lola Montez und die Jesuiten : Eine Darstellung der jüngsten Ereignisse in München, Hamburg : Hoffman und Campe; Francis, 1848, Lola Montes und ihre politische stellung in München; nach einem englischen berichte und mit einem vorwort des deutschen herausgebers, München, druck der J. Deschler’schen offizin.

- See, for example, the ‘Whip Smart’ trilogy by Kit Brennan (2012-2014).

Next post

The next post will report on the progress of Fame and the Female Dancer.