Barbara Campanini, ‘La Barbarina’ (1721-1799)

BY MOIRA GOFF

On 15 October 1740, Barbara Campanini (billed as ‘La Barberini’) made her London debut at Covent Garden. The bills show her dancing with George Desnoyer and announce the performance as ‘the first time of her appearing on the English stage’.1 The performance was commanded by the King and attended by George II with his son Prince William and his daughters the Princesses Amelia, Caroline and Louisa. The bills do not tell us what the new Italian prodigy danced.

La Barbarina (as she is usually called) had, in fact, arrived in England some months earlier. She had made notable appearances at Cliveden on 1 and 2 August 1740 before Frederick, Prince of Wales and his wife Augusta. According to a report in the London Daily Post for 5 August 1740, the main entertainment was ‘a Dramatic Masque call’d Alfred, written by Mr. Thomson, in which was introduc’d Variety of Dancing, very much to the Satisfaction of their Royal Highnesses and the rest of the Spectators’. The royal couple were said to have been particularly impressed with ‘the Performance of Signora Barberini (lately arriv’d from Paris) whose Grace, Beauty, and surprising Agility, exceeded their Expectations’. Her engagement for these performances must surely have involved George Desnoyer, dancing master to Prince Frederick and his family.2

The Italian ballerina’s engagement by Covent Garden preceded her appearance at Cliveden for it was under discussion as early as December 1739.3 The Daily Gazetteer for 25 July 1740 printed ‘Part of a Letter from Mr. Rich to a Friend’ dated from Paris on 16 July 1740 which showed that an agreement had already been made:

Dear Sir,

I reached Paris on Friday last, and the next Morning went with your Friend Mr. — to pay a Visit to the Signiora Barberini: And not to enter into the Particulars of our Treaty, I shall only tell you at present, that we have agreed and signed Articles, and she sets out with me for England in four or five Days. I am, Sir,

Your Obliged Humble Servant,

John Rich

The Daily Gazetteer’s reporter added that the dancer ‘happens to be an Italian Beauty, who greatly surprised the French Nation with her elegant Performances in the Opera at Paris last Winter’.

Signora Barbarina had made her debut at the Paris Opéra on 14 July 1739 dancing in Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Les Fêtes d’Hébé. The composer had written an entrée vive, a loure, a minuet and a gavotte to show off her virtuosity.4 Her debut was reported in the Mercure de France for July 1739:

La Dlle Barbarina, a young dancer from Parma, hardly sixteen years old, drew a great crowd, with an Entrée that she danced with many graces, as well as precision and lightness; she performed entre-chat à huit with surprising vivacity, and the style of her dancing is in the same line as Mlle Camargo.

The writer drew attention to her many attractions, adding that these allowed one to believe that ‘she would become a dancer of the first rank, if she wasn’t already’.5 In the August issue, the Mercure de France provided another report of Signora Barbarina’s dancing. This time she had given a pas de deux after Les Fêtes d’Hébé partnered by another Italian dancer (who was not named but was presumably her teacher Antonio Rinaldi, known as Fossano):

These two excellent sujets are generally applauded by an enormous crowd: it must be admitted that one could see nothing so surprising and singular as this pantomime and burlesque dancing.

These reports reveal that the dancing skills La Barbarina brought to London were both technical and expressive.

Barbara Campanini danced at London’s Covent Garden Theatre from October 1740 to April 1741, before returning to the Paris Opéra for some months. She was back at Covent Garden in October 1741 and stayed until May 1742, although she was absent from the stage from November until mid-January apparently because of illness. La Barbarina returned to London for the 1742-1743 season, dancing in the Italian operas at the King’s Theatre, her last stage appearances in England. For the purposes of this post, I will concentrate on her two seasons at Covent Garden.

Barbara Campanini was not the first Italian performer to come to London, although almost all her predecessors had been first and foremost exponents of the commedia dell’arte and not virtuosic dancers. She marked a change which would take root over subsequent decades.

Initially, the bills were silent as to the dances given by La Barbarina and Desnoyer, but on 3 November 1740 they were advertised in the duet Italian Peasants. This was easily their most popular dance, with at least 20 performances during the 1740-1741 season, and may have come from La Barbarina’s own repertoire. Italian Peasant dances quickly became established on the London stage, perhaps as a result of her performances. Also popular was the Tirolese or Tyrolean Dance ‘between a Hungarian and two Tyroleans’, first given by La Barbarina, Desnoyer and Haughton on 28 November 1740. This had twelve performances in 1740-1741 and another eight in 1741-1742, although it seems to have had no lasting influence in London. Was La Barbarina the Hungarian with the two men as the Tyroleans, or was the piece more complicated than that? The music for Italian Peasants and the Tyrolean Dance was included in the first volume of The Comic Dances by Johann Adolf Hasse and others published in 1741. The music for both of these dances has three sections, each with a different time signature, giving them the form of a short suite.

Over the course of her two seasons at Covent Garden, La Barbarina performed in some fifteen solo, duet or group dances as well as three afterpieces. Her solos included a Louvre, first given on 20 December 1740 and repeated a number of times during the season. It may, possibly, have been the dance she performed in Paris to Rameau’s specially composed loure for her in Les Fêtes d’Hébé. The duet Louvre ‘and Minuet’ that she performed several times with Desnoyer and others, almost always at benefit performances, was probably Pecour’s Aimable Vainqueur which had become a favourite in London’s theatres. There was also her Tambourine, generally given as a duet with Desnoyer, which has attracted notice from several scholars in recent years.

While these dances may have come from, or been closely related to, La Barbarina’s own earlier repertoire, the group dance the Rural Assembly may have owed as much (if not more) to her partner Desnoyer. This ‘new Grand Ballet’ was introduced on 21 January 1742 within a performance of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. It was subsequently performed within As You Like It and The Way of the World before settling into the entr’actes alongside a variety of mainpieces. Desnoyer was a ‘Chasseur’ supported by dancing ‘Pastors’ and Shepherdesses, while La Barbarina was a ‘Nymph of the Plain’ accompanied by a ‘Cottage Nymph’ (danced by her sister Signora Domitilla) with ‘Two Nymphs of the Vale and a Sylvan’. This ‘Grand Ballet’ had 26 performances between 21 January and 2 June 1742 but was not revived subsequently, probably because of the loss of its two leading dancers (Desnoyer retired from the stage at the end of the season, while La Barbarina returned to London only to dance at the King’s Theatre). The music, published in the second volume of Hasse’s Comic Tunes, again has three sections but seems too short to support what was apparently quite an ambitious divertissement if not a short pastoral ballet.

Over her two seasons at Covent Garden, La Barbarina appeared in three afterpieces. Pan and Syrinx, given on 16 and 17 December 1740, may well have been a small opera – perhaps that by Theobald and Galliard last given during the 1726-1727 season. Orpheus and Eurydice (first performed on 24 October 1741) was described in the bills as ‘a New Dramatic Entertainment of Dancing combin’d with a New Pantomime in Grotesque Characters’ in which she danced yet another Nymph. The Royal Chace was a popular pantomime, but according to the newspaper advertisements La Barbarina seems mainly to have performed her most successful entr’acte dances alongside it. Although, on 2 February 1741, she was billed as a Garden Nymph within the cast list and on 6 February the advertisements included ‘a new Dance between a Garden Swain and Nymph’ by her and Desnoyer. In all, she danced within or alongside The Royal Chace at 26 performances during 1740-1741.

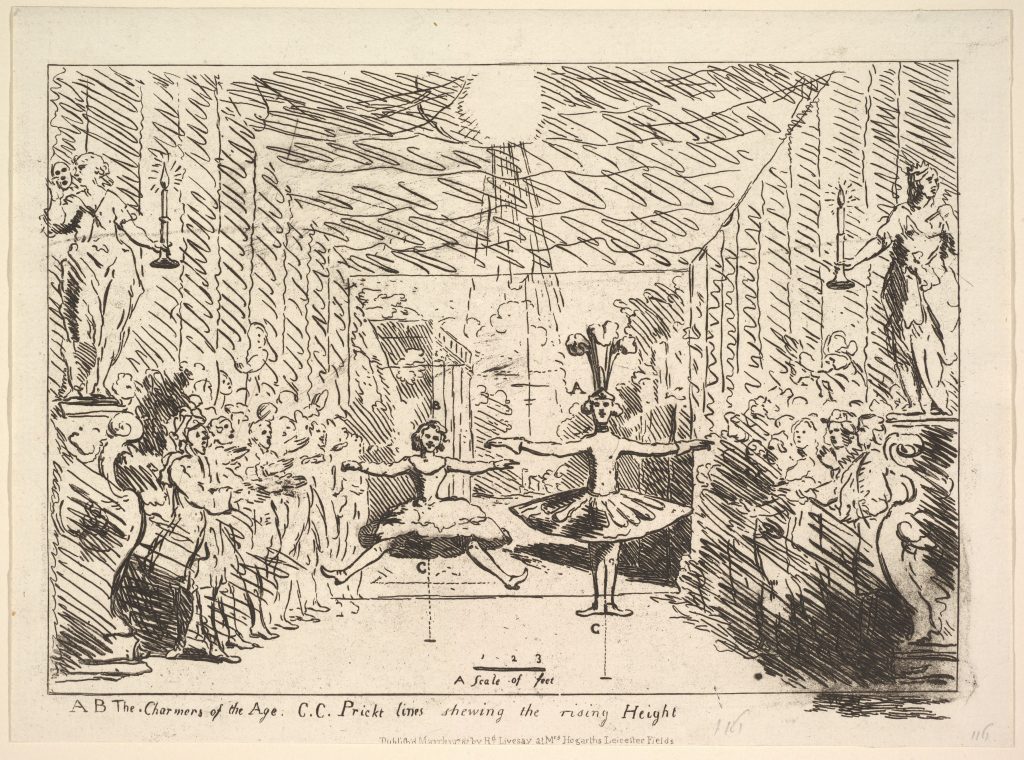

How did Barbara Campanini dance in these entr’acte choreographies? In particular, what was it about her style and technique that provoked William Hogarth to depict her as well as Desnoyer so cruelly in his satirical sketch ‘The Charmers of the Age’?

There is a question mark over Hogarth’s sketch, for the original does not survive and we have only an etching made nearly twenty years after the artist’s death. The sketch has been dated to 1742, when La Barbarina and Desnoyer were dancing together in London and Hogarth (presumably) saw them on stage. Although they are depicted side by side, they cannot be said to be dancing a duet for Hogarth shows them in quite different positions. Both are apparently jumping, but in such different styles that it is hard to escape the conclusion that Hogarth was simply exaggerating what he most disliked about their respective techniques.

Although he included the figure of Desnoyer in several other works, this was Hogarth’s only image of La Barbarina. She is shown in the air with her legs in a wide second position, which might relate to the modern step known as pas échappé or she could be executing an entrechat beginning and ending in that position – unless Hogarth was deliberately visualising her in a step from the Italian grottesco tradition that he had seen performed by others. The point of the image is actually the opportunity it provides for an obscene pun, with the artist capitalising on La Barbarina’s virtuosity to achieve this. Hogarth set out his views on dancing in his 1753 treatise An Analysis of Beauty. His preference was for ‘serpentine or waving lines’ rather than the rigidly straight limbs in ‘The Charmers of the Age’. He also gave as his opinion that ‘such uncouth contortions of the body as are allowable in a man would disgust in a woman’, suggesting that his sketch was also intended to reveal La Barberina’s dancing as too expansive and forceful – too masculine – for his taste.

During her career, the ballerina was the subject of several portraits. The best-known of these is probably the full-length, life-size portrait by Antoine Pesne, painted around 1745 not long after she had been engaged to dance for Frederick II in Prussia.

La Barbarina is shown dancing in an elaborate dress overlaid with a leopard skin. She holds a tambourine aloft in her left hand and seems to be gesturing to it with her right. Her head is turned slightly to her right although she looks out of the canvas at her audience. Her feet and legs replicate those of La Camargo in Lancret’s famous portrait now in the Wallace Collection in London, although the positions of her arms and upper body differ. Was Pesne making a mute comparison between the two ballerinas, or had Camargo’s pose already been adopted as emblematic of a stage dancer? Apart from the energy and sense of movement in La Barbarina’s figure, Pesne’s portrait only hints at the ‘surprising Agility’ of this Italian prodigy that so disturbed William Hogarth.

Notes

1) Information about performances, including quotations, is taken from The London Stage 1660-1800. Part 3: 1729-1747, ed. Arthur H Scouten (Carbondale, 1965), unless otherwise indicated.

2) Moira Goff, ‘Desnoyer, Charmer of the Georgian Age’, Historical Dance, 4.2 (2012), 3-10.

3) For these earlier negotiations, which reveal that La Barberina was to be engaged for two seasons at Covent Garden, see Lowell Lindgren, ‘Musicians and librettists in the correspondence of Gio. Giacomo Zamboni (Oxford, Bodleian Library. MSS Rawlinson Letters 116-138)’, Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 1991, No. 24, 1-194 (pp. 175-176).

4) For the additional dances, see under ‘Campanini, Barbara’, in A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, edited by Philip H. Highfill, Kalman A. Burnim and Edward A. Langhans (Carbondale, 1973-1993); also, see under ‘Barbarina, La’ in International Encyclopedia of Dance, edited by Selma Jeanne Cohen (New York, 1998). Study of the musical sources, however places the revisions before Barbarina’s arrival, ‘from 23 June [1739] with rev[ised]. 2nd entrée’; see under ‘Rameau, Jean-Philippe: Works’, by Graham Sadler and Thomas Christensen in Grove Music Online, retrieved 22 December 2021 from https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000022832.

5) Mercure de France, July 1739, p. 1632: ‘la Dlle Barbarina, jeune Danseuse de Parme, qui n’a pas seize ans accomplis, attira un très grand concours, par une Entrée qu’elle dansa avec beaucoup de graces, & plus encore de justesse & de legereté; elle passe l’entre chat à huit avec une vivacité surprenante, & son caractere de danse est dans celui de Mlle Camargo’, ‘qu’elle deviendra une Danseuse du premier ordre, si elle ne l’est déja’. Translations by the author.

6) Mercure de France, August 1739, p. 1850: ‘Ces deux excellens Sujets sont generalement aplaudis par un concours prodigieux: it faut avoüer qu’on n’a peut être encore rien vû, dans ce caractere Pantomime & burlesque, de si surprentant ni de si singulier’.

7) For Italian dancers in London, see Sarah McCleave, ‘Danzatori italiani a Londra nel settecento’, La Danza Italiana 3, ed. José Sasportes (2011), 63-136.

8) Johann Adolf Hasse, The Comic Tunes &c. to the Celebrated Dances. Book I (London, [1741]), pp. 16-21. See also Judith Milhous, ‘Hasse’s “Comic Tunes”: some dancers and dance music on the London stage, 1740-1759’, Dance Research, 2.2 (Summer 1984), 41-55.

9) The ballroom dance Aimable Vainqueur, choreographed by Guillaume-Louis Pecour to music from Campra’s opera Hésione, was first published in Beauchamp-Feuillet notation in 1701. It was regularly republished until 1765 and was often performed at benefit performances in London’s theatres until the 1770s.

10) For a short discussion of the tambourin with references to other accounts of the dance, see Samantha Owens, ‘“Grace, Beauty, and Surprising Agility”: Representations of Barbara Campanini, 1742-1748’, in With a Grace not to be Captured: Representing the Georgian Theatrical Dancer, 1760-1830, ed. Michael Burden and Jennifer Thorp (Turnhout, 2020). Music and Visual Cultures 3, 105-119 (pp. 105-107).

11) Hasse, The Comic Tunes &c. Book II (London, [1741]), pp. 8-9.

12) The attribution to Hogarth is accepted by Ronald Paulson, Hogarth’s Graphic Works (London, 1989), no. 153.

13) For the figure of Desnoyer in ‘The Charmers of the Age’ and other works by Hogarth, see Moira Goff, ‘The Celebrated Monsieur Desnoyer, Part 2: 1734-1742’, Dance Research, 31.1 (2013), 78-93 (pp. 89-90).

14) Raoul Auger Feuillet, Chorégraphie (Paris, 1700), p. 86, ‘Table des Entre-chats et demy Entre-chats’.

15) William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty, ed. Ronald Paulson (New Haven, 1997), p. 110.

16) For a survey of the surviving portraits of Barbara Campanini, see Owens, ‘“Grace, Beauty, and Surprising Agility”’, pp. 113-119.

Images

- ‘The Charmers of the Age’, caricature of Barbarina Campanini and Desnoyer. Richard Livesay (engraver) after William Hogarth. Published by Richard Livesay [London], 1 March 1782. From the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons, Public domain.

2) Portrait of Barbarina Campanini by Antoine Pesne (Circa 1745). From the collection at Sans Souci Palace, Potsdam. Photographer unknown. Wikimedia Commons, Public domain.

Next post

‘Watching the Nautch Girls of India’, by Aryama Bej, will appear in January 2022.