Sarah McCleave

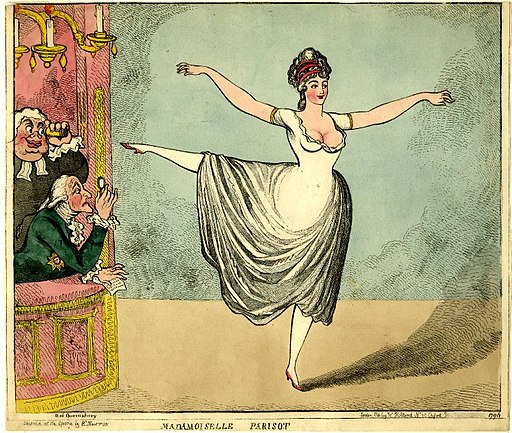

Mlle Rose Parisot (1777?-after 1837) was a young French dancer whose reception in London is well documented in the contemporary press, and also through satirical prints as well as two portraits. From her King’s Theatre début in February 1796 she attracted attention for her looks and the physicality of her movement, as this Morning Chronicle review (10 Feb. 1796) reveals:

Madamoiselle PARISOT, a new dancer from Paris … is a most beautiful figure, about 18 years of age, and with a face full of expression. A little divertissement has been got up to introduce her to the public, and she displayed powers in the grand character extremely striking. Her attitudes are graceful, her step firm, her balance is positively magical, for her person was almost horizontal while turning as on a pivot on her toe. From the specimen of last night, she is a great acquisition to the Theatre; and if her talent for acting be equal to her dancing and figure, they will be able to give us ballets in good style.

Parisot had previously served as première danseuse in Rouen and had also danced in Paris (2). Press reports in London suggest that she was obliged to become professional through the events of the French Revolution (3), further indicating that she supported her mother and a sister. There’s no sense, however, that she enjoyed any familial protection, or indeed that she had any valuable guidance or support during what would prove to be a turbulent career for this young foreign dancer. The Morning Chronicle review touches on two issues that would dominate her reception: her beautiful figure, and the unusual attitude she introduced to the London stage. Towards the end of her first London season we are told ‘Parisot, the beautiful Parisot, captivates, by her curvets and her attitudes, all the hearts in Fop’s Alley’ (4). Her winning combination of curves and poses stimulated strong responses from a certain kind of theatre spectator.

This blog post reproduces two satirical prints of Parisot’s spectators (5). Above we have Newman’s print, which shows Parisot being ogled by the then 72-year-old William Douglas, 4th Duke of Queensberry. It’s likely the cleric pictured is Shute Barrington, Bishop of Durham, who openly censored the immorality of current stage practices. Below we have Isaac Cruickshank’s ‘A Peep at the Parisot – with Q in the Corner’. So once again the faithful Duke of Queensbury – an inveterate gambler popularly known as ‘Old Q’ – is in attendance. As the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (5 May 1796) reported, ‘the Duke of QUEENSBERRY looks not at any other garter than that appertaining to the enchanting leg of PARISOT’. The experienced satirist Cruickshank focuses on those enchanting legs, the outline of which can be appreciated underneath Parisot’s costume. By drawing the opening in her skirt – a detail we don’t have in the Newman – Cruickshank brings a greater immediacy to the scenario. We apprehend the young dancer’s level of exposure without seeing beneath the skirt ourselves.

While the furore that Parisot’s attitudes caused was a lively enough introduction to the London theatre scene, she had to cope with an even more significant scandal the following season.

To be continued.

Notes

1) ‘Arts and Culture.’ Morning Chronicle [1770], 10 Feb. 1796. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, Gale Primary Resources, accessed 26 Sept. 2021.

2) The Biographical Dictionary of Actors indicates Parisot’s pre-London experience; for a most interesting blog that includes some detail about her press coverage from the age of 14, see Naomi Clifford, ‘Mademoiselle Parisot’s shocking pirouettes put London in a spin’, in Books and Talks (blog), 10 Sept. 2018. https://www.naomiclifford.com/portfolio/mademoiselle-parisot/, accessed 26 Sept. 2021.

3) ‘News.’ Oracle, 18 Aug. 1796. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, Gale Primary Resources, accessed 26 Sept. 2021.

4) ‘News.’ Sun, 9 June 1796. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, Gale Primary Resources, accessed 26 Sept. 2021.

5) For further on these men, and the notion that they are the object of the satire rather than the dancer, see Caitlyn Lehmann, ‘Madame Rose Parisot, “Attitudinarian”‘, in vintage pointe (blog), no date. https://vintagepointe.org/madam-rose-parisot-attitudinarian/, accessed 26 September 2021.

Images

- Richard Newton. 1796. ‘Madamoiselle Parisot.’ London: William Holland. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Accessed 21 April 2021.

- Issac Cruikshank (artist). 1796. ‘A Peep at the Parisot with Q in the Corner.’ London: S.W. Fores. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1137209/h-beard-print-collection-print-cruikshank-isaac/. Accessed 21 April 2021.

Next Post

“Three’s a Crowd,” a continuation of the account of Mlle. Parisot’s London reception, will appear on 10 October.