Comintern Collection MS 57

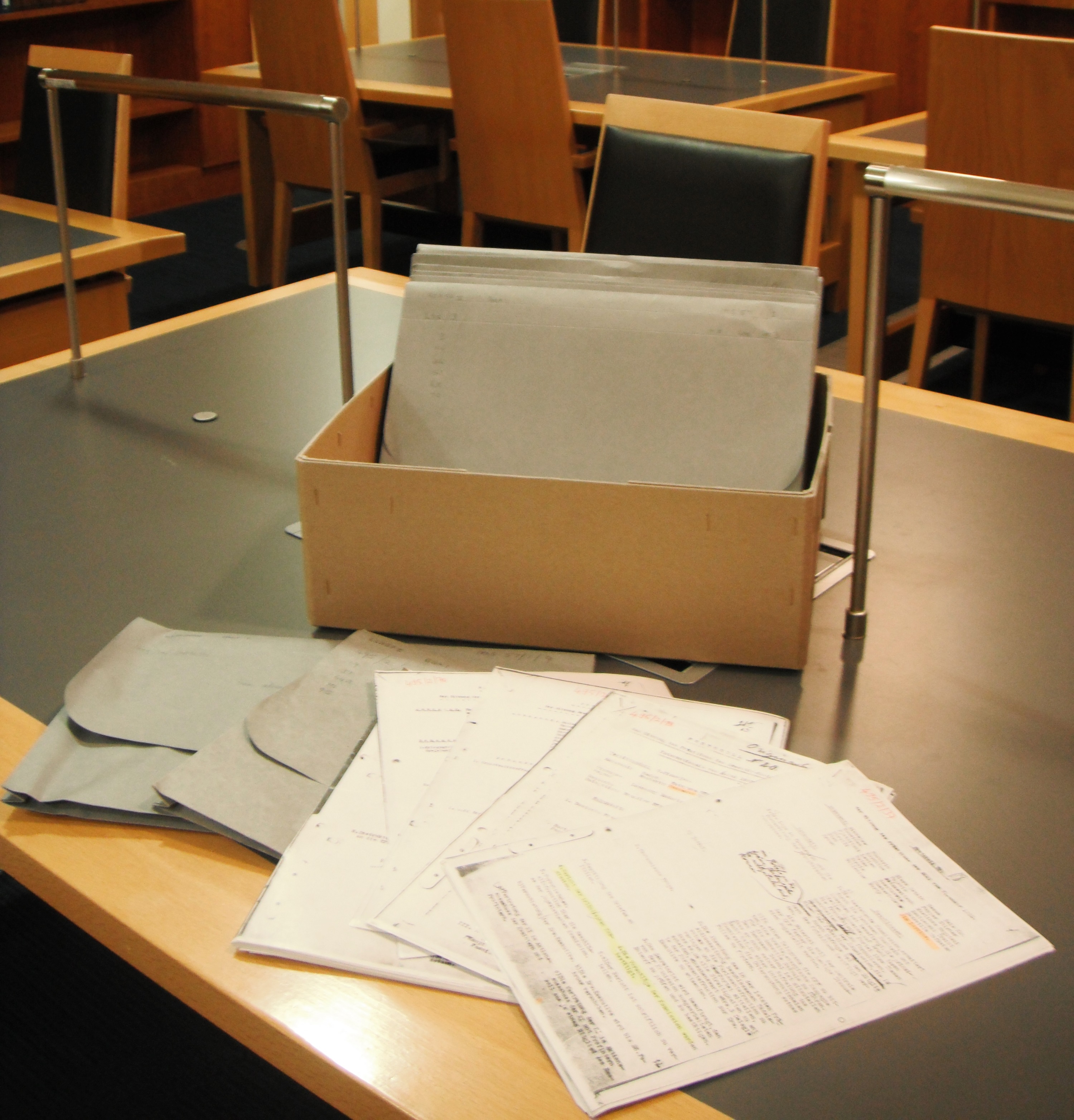

Between 1993 and 1995, two Irish academics – Dr Barry McLoughlin (University of Vienna, Austria) and Dr Emmet O’Connor (University of Ulster, Northern Ireland) – were quick to take advantage of unprecedented access to c. 60 million pages of archival material held in the Russian Centre for the Conservation and Study of Modern History Documents (RTsKI).[1]

Essentially inaccessible to foreigners until 1991[2] (when the RTsKI archive was incorporated into the state archival system and placed under direct ministerial responsibility) and subject to tighter access restrictions since the mid-1990s, the adoption of a more liberal regime in the Russian Federation in the years following Perestroika provided the two scholars with an unparalleled window of opportunity to explore this vast archive.

Focusing their research on materials relating to the Communist International and to Ireland in particular, McLoughlin and O’Connor, in the course of repeated trips to Moscow, were able to select, microfilm and catalogue approximately 4000 pages of archival material (subsequently off-printed). Following the generous donation of both microfilms and off-prints by the two researchers to Queen’s University Belfast in 2011-12, the collection is held as MS 57 (Comintern Collection) in the McClay Library’s Special Collections. Unique outside of Russia, the Comintern papers provide considerable insight into the personalities, organisation and policy development of Irish Communism from 1920 – 1943.[3]

The Comintern:

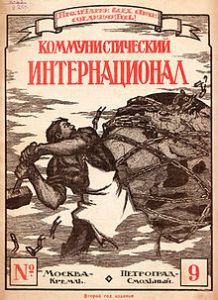

The Comintern (also known as the Communist International or the Third International) was an association of national communist parties, founded by Lenin in 1919. Emerging from the disintegration of the socialist Second International over the issue of the First World War – with Lenin’s faction rejecting both pacifism and nationalism and seeking instead to transmute the ‘War of Nations’ into a transnational class war – the aim of the Third International was to fight “by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and for the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the State”.[4] In establishing the Comintern as the controlling body of all Communist parties, Lenin’s aim was to instate Communism as one world party.

In the ensuing years, the Comintern underwent various policy turns, but remained in existence until 1943, when it was dissolved by Stalin. All Communist parties affiliated to the Comintern had to accept 21 conditions of membership, including the ratification of every party programme by a regular Congress of the Communist International or by the Executive Committee of the Communist International. National Communist Parties were expected to provide Moscow with regular reports on their activities and to conduct their policies in accordance with the Comintern’s current party line.[5]

Ireland and the Comintern:

Whilst affiliation to the Comintern would seem to be of obvious and immediate benefit to smaller communist parties in countries like Ireland, the relationship between the Comintern and the various incarnations of the Communist Party in Ireland was not as straightforward as may have been supposed: “the Irish had a strong sense of their own situation, were not overwhelmed by the Soviets, and Moscow generally accepted Irish advice on policy application”.[6] During the 1920s, the Comintern, as O’Connor points out, “attached exceptional importance to Ireland for the potential of its anti-imperialist forces to foment revolution at home, enlist the Irish diaspora, and encourage unrest in Britain and the Empire”, [7] but it was not until 1929 that the Comintern succeeded in establishing direct and regular contact with Ireland.

The first Communist Party of Ireland was launched in 1921, displacing the Socialist Party of Ireland as the endorsed Irish Comintern affiliate. Roddy Connolly (son of James Connolly and close associate of Lenin) was instrumental in the emergence of the CPI, becoming both its President and the editor of the party’s newspaper, The Workers’ Republic. However, the party made little headway, being dissolved by the Comintern in 1924, in favour of Jim Larkin’s Irish Workers’ League. Far from advancing the aims of the Comintern, Larkin proved to be somewhat of liability to them. Despite being recognised by the Comintern as the Irish section of the world communist movement, the “IWL never functioned as a communist party, and ‘the big one’ had an extraordinarily troubled relationship with the Comintern.”[8]

of Ireland as the endorsed Irish Comintern affiliate. Roddy Connolly (son of James Connolly and close associate of Lenin) was instrumental in the emergence of the CPI, becoming both its President and the editor of the party’s newspaper, The Workers’ Republic. However, the party made little headway, being dissolved by the Comintern in 1924, in favour of Jim Larkin’s Irish Workers’ League. Far from advancing the aims of the Comintern, Larkin proved to be somewhat of liability to them. Despite being recognised by the Comintern as the Irish section of the world communist movement, the “IWL never functioned as a communist party, and ‘the big one’ had an extraordinarily troubled relationship with the Comintern.”[8]

By the 1920s, Moscow decided that the time had come to change tack, and to focus on the “Bolshevisation” of the Comintern. This renewed focus manifested itself in two key ways. Firstly, promising young members of the national parties were selected to spend a year studying at the International Lenin School, in order to gain a better understanding of both Marxist theory and effective strategy. Given the consistently small size of the Communist movement in Ireland, a perhaps surprisingly large number of Irish students studied at the International Lenin School, amongst them, Jim Larkin’s son, ‘young Jim’.[9] Secondly, various communist front organisations were set up, with the aim of attracting non-party members who nevertheless sympathised with the Party on certain issues; in Ireland, this led to the renewal of the auxiliary relationship between international communism and the IRA.

Larkin Sr.’s break with the Comintern in 1929 was followed by a redoubling of Comintern efforts in Ireland, culminating in the creation of the Revolutionary Workers’ Groups in 1930 and the establishment of the second Communist Party of Ireland in 1933. Significant gains were made: in O’Connor’s assessment, “[…] the RWG’s tally of some 340 in November 1932 represented the peak membership of the Comintern in Ireland.[10] This success, however, was short-lived, as the impact of Catholic Church’s denunciation of communism and the IRA’s disassociation of itself from the CPI were felt. Numbers dwindled further after the break down of the Republican Congress, and by 1941, when the CPI was formally dissolved (in the interest of preserving Irish neutrality in World War II) only 20 activists remained.[11]

Scope and significance of the Comintern Papers:

The contents of the 4000-page strong Comintern Papers shed important light on the Irish labour movement and on the history of Communism in Ireland. The collection includes various documents from the departments and standing committees of the Executive Committee of the Communist International, including speeches, reports, correspondence, agendas, minutes, posters, telegrams, and handwritten notes. The materials also detail contact between the Comintern and various Irish groups from 1919-1939. Whilst the material relating to the first Irish communist groups is rather patchy in coverage, the 1921-1935 period is comprehensively documented, with the collection containing substantial material on the first Communist Party of Ireland; Larkin’s troubled relationship with Comintern; and on the ‘third period’ of Comintern-Irish relations.

This MS collection thus contains essential and hitherto inaccessible information on Comintern and Soviet perspectives on Ireland; the activities of other Comintern organisations such as the Profintern, the International Lenin School and the fronts; and the relationship between the Comintern and national sections more generally. Moreover, the collection sheds valuable light on the activities and motivations of prominent personalities such as Roddy Connolly, Jim Larkin and Sean Murray; and on the organisation and operation of the Communist groups within Ireland, including evidence of their (sometimes fraught) relationships with the Communist Party of Great Britain. The papers also contain material relevant to scholars of Irish Republicanism and of radical movements in early C20 Ireland more broadly.

Thanks in no small part to the Comintern Papers, “the secretive Communists” are, as the foremost expert on this collection observes, “probably Ireland’s best-documented political movement.”[12]

Launch of Cominern Papers, McClay Library, QUB.

The launch of the Comintern papers was marked by a special meeting of the QUB History Staff/Postgraduate Seminar Series on 6th February 2015, with keynote speakers Dr Emmet O’Connor and Dr Barry McLaughlin. The occasion also marked the launch of Dr McLaughlin’s new monograph, Fighting for Republican Spain, 1936-38: Frank Ryan and the Volunteers from Limerick in the International Brigades.

Coverage of the launch was broadcast on NVTV’s Focal Point on Monday 16th February.

Works cited:

McLoughlin, Barry and Emmet O’Connor. “Sources on Ireland and the Communist International, 1920-1943.” Saothar 21 (1996) 101-107.

O’Connor, Emmet. ”Bolshevising Irish Communism: The Communist International and the Formation of the Revolutionary Workers’ Groups, 1927-31.” Irish Historical Studies 33.132 (Nov. 2003) 452-469.

O’Connor, Emmet. Reds and the green: Ireland, Russia, and the Communist Internationalists, 1919-1943. Dublin: UCD Press, 2004.

Minutes of Second Congress of the Communist International. Evening Session of 4 August 1920. https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/2nd-congress/ch10a.htm Accessed 25.03.2015

[1] Formerly, the Central Party Archive of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the Institute for Marxism-Leninism; since 1999, the Russian State Archive for Social and Political History (RGASPI).

[2] Access was “restricted to approved Communist Party Members who were allowed to see material on their own party only”. (O’Connor, 2004, 6)

[3] In addition to the manuscript listing, a detailed overview of the contents of the papers can be found in McLoughlin & O’Connor, 1996.

[4] Minutes of Second Congress of the Communist International. Evening Session of 4 August 1920. https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/2nd-congress/ch10a.htm Accessed 25.03.2015

[5] McLoughlin & O’Connor, 103.

[6] McLoughlin & O’Connor, 107.

[7] O’Connor, 2003, 452.

[8] O’Connor, 2004, 3.

[9] O’Connor, 2003, 454.

[10] O’Connor, 2004, 3.

[11] O’Connor, 2004, 3.

[12] O’Connor, 2004, 6. The CPI archives were donated to Dublin City Archive in 2011.