Literary Magazines in Ireland, from 1904 to the Present-Day

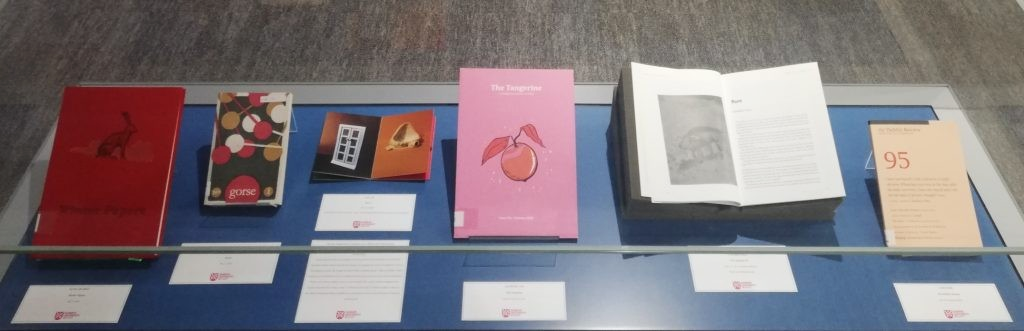

A selection of literary magazines and journals held by Special Collections & Archives is currently on display on Floor One of the McClay Library. This exhibition highlights the significance of “little magazines”1 in Ireland, and their ongoing impact on this island’s literary landscape. Along with showcasing literary developments in Ireland, these magazines are a valuable resource in understanding cultural, political and societal trends and concerns throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. All items on display are available for consultation in the Special Collections Reading Room.

Early 20th Century: “We invite the thinkers, dreamers and observers…to communicate through our pages their thoughts, reveries and observations.”2

Like many little magazines published in the early twentieth century, Irish literary magazines such as Dana, Ulaḋ, and The Klaxon were short-lived, often due to issues surrounding censorship, together with a lack of financial support. Despite the obstacles that they faced, these magazines had a profound impact in Ireland at a crucial time in the country’s development. In Belfast, Ulaḋ: A Literary and Critical Magazine, ran for four issues between 1904-1905. It gave voice, according to Eugene McNulty, “to (nationalist) Ulster, a voice that spoke to the rest of Ireland but also spoke to Ulster itself.”3 Dana: An Irish Magazine of Independent Thought, also published between 1904-1905, can be credited with publishing the short poem “Song” by James Joyce, a little-known author at the time. One of Dana’s editors later refused to publish Joyce’s essay “A Portrait of the Artist”, claiming that it was incomprehensible.

Twenty years later, during winter 1923-24, The Klaxon rolled off the presses, promising “a whiff of Dadaist Europe to kick Ireland into artistic wakefulness.”4 The magazine, which branded itself as fiercely modernist, was not so progressive as to imagine women gaining enjoyment from reading Joyce’s Ulysses. In what was the first positive magazine review for the book published in the Irish Free State, Lawrence K. Emery (a pseudonym for The Klaxon’s editor A.J. Leventhal) stated: “Ulysses is essentially a book for the male. It is impossible for a woman to stomach its egregious grossness.”5 The Klaxon ran for one issue, with Leventhal and other contributors going on to start another avant-garde periodical called To-Morrow, which was published for two issues in 1924.

The 1929 Censorship of Publications Act brought with it continued challenges for the progression of literature in Ireland. It enshrined, according to Dr Aoife Bhreatnach, “an ideology that was deeply suspicious of expressions of human complexity.”6 In 1940, despite the barriers presented by the state’s censorship regime, a new magazine was founded in Dublin, featuring poetry, journalism, and autobiography, with a particular emphasis on the short story. The Bell, established and edited by Seán Ó’Faoláin, was a monthly magazine ambitious about publishing work that turned a realist eye on the present and looked towards the future. Eager to find work that cleared away “the romantic myths of the past”7 and instead reflected a modern, independent Ireland, Ó’Faoláin urged writers to turn their attention to Dublin where “a native government, a corps diplomatique, a Church of unbounded influence and occasional panoply, a growing middle-class full of energy, a raw, new industrialism” were begging to be depicted.8 In 1946, Ó’Faoláin resigned, with Peadar O’Donnell taking on the role of editor until The Bell’s last issue in 1954.

Mid-Late 20th Century: “We expect to print writers of varied beliefs and backgrounds. Not only protestants and catholics, unionists and liberals, but humanists, anarchists, atheists, mystics, communists, etc.”9

By the 1960s and 70s in Ireland, the rise in new magazine titles had fostered the emergence of a fresh, diverse group of voices, many of whom would go on to become our most celebrated writers. Poets and fiction writers such as Seamus Heaney, Medbh McGuckian and Dermot Healy had some of their earliest work published in little magazines and journals (The Dublin Magazine, The Honest Ulsterman, and North, respectively). In university circles, a decidedly experimental approach to publication was explored, with magazines such as Crab Grass: Poetical Sonatas (produced during the early 1970s by Queen’s University Belfast architecture students) publishing a mix of illustrations, concrete poetry and avant-garde music scores. In Trinity College Dublin, Icarus magazine first took flight in 1950 and has been published regularly ever since, making it the oldest continuous publication of its kind in Ireland. Notable contributors have included William Burroughs, Eavan Boland and Louis MacNeice, and former editors include Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin and Michael Longley.

Smaller communities and provincial literary society’s also published magazines during this time, from Nenagh, Co. Tipperary’s lesser known Wordsnare: A Magazine of Nenagh Verse (1974-1977), to the highly regarded Kilkenny Magazine: An All-Ireland Literary Review (1960-1970). The latter can be credited with the early publication of Brian Friel, having featured the playwright and author’s short story “The Visitation” in Issue Five, 1961, a year before the publication of his first collection The Saucer of Larks.

Present-Day: “things being various”10

Today, Ireland’s literary landscape is thriving, with acclaimed writers such as Louise Kennedy, Sally Rooney, Wendy Erskine and Michael Magee gaining early recognition through publications in magazines such as The Stinging Fly and The Tangerine. The former, founded in Dublin in 1997 by Declan Meade and Aoife Kavanagh, has long acted as a launchpad for emerging writers. It also facilitates dialogue amongst creatives and is often credited with introducing both writers and readers to the notion of a literary community.11 The Tangerine, founded by Queen’s University Belfast alumni in 2016, is a print magazine concerned with “things being various”, offering a home, its editors say, for work that may not be published elsewhere.12

Susan Tomaselli, editor of the avant-garde journal gorse, has spoken of the potential of the modern print magazine to showcase strange and innovative writing – work that blurs the lines between visual poetry, creative non-fiction, and autobiographical fiction.13 Recent titles such as Tolka, Channel and The Pig’s Back maintain a similar DIY publishing ethos, promoting work as varied as their predecessors and gaining a wide readership along the way. The modern literary magazine has moved firmly away from the parochial view of Irishness that Ó’Faoláin sought to reject in the 1940s, instead looking outward and providing a platform for a plurality of voices in Ireland and beyond. In this digital age of screens, social media, and waning attention spans, the continued appetite for literary magazines—tactile, cultural artefacts—feels nothing short of revolutionary.

Blog post written by Laura Sheary, Library Assistant, Special Collections & Archives at Queen’s University Belfast.

- According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “little magazines” are periodicals directed at a readership with serious literary, artistic, or other intellectual interests, usually having a small circulation and considered to appeal to a minority. little magazine, n. meanings (oed.com) ↩︎

- The Editors, “Introductory”, Dana: A Magazine of Independent Thought (May, 1904), p. 3. ↩︎

- Eugene McNulty, The Ulster Literary Theatre and the Northern Revival (Cork: Cork University Press, 2008), p. 78.︎ ↩︎

- Lawrence K. Emery, “Confessional”, The Klaxon (Winter,1923-24), p. 1. ↩︎

- Lawrence K. Emery, “The Ulysses of Mr. James Joyce”, The Klaxon (Winter,1923-24), p. 19. ↩︎

- Dr Aoife Bhreatnach, “Habitually, rankly immoral: State censorship in Ireland after 1930” (Lecture by Dr. Aoife Bhreatnach – The National Archives of Ireland), Accessed 12 Sept. 2024 ↩︎

- Phyllis Boumans, Elke D’hoker, Declan Meade, The Writer’s Torch: Reading Stories from The Bell (Dublin: The Stinging Fly Press, 2023), p. ix. ↩︎

- Boumans et al, p. xi. ↩︎

- “About Us”, The Honest Ulsterman, (Honest Ulsterman – About Us (humag.co)), Accessed 19 Sept. 2024 ↩︎

- Tara McEvoy, “Editorial”, The Tangerine (Issue One, Winter 2016), p. 6. ↩︎

- “How a Tiny Literary Magazine Became a Springboard for Great Irish Writing”, The New York Times, (How a Tiny Literary Magazine Became a Springboard for Great Irish Writing (nytimes.com)), Accessed 16 Sept. 2024 ↩︎

- “The Tangerine: a cultural magazine for a Belfast that’s turning the page”, The Irish Times, (The Tangerine – The Irish Times Accessed 16 Sept. 2024 ↩︎

- “Interview with gorse”, 3:AM Magazine, (Interview with gorse (3ammagazine.com)) Accessed 12 Sept. 2024 ↩︎

Brilliant exhibition! Periodicals are fairly neglected in literary studies but were often highly influential and interesting!

Thanks for your comment, Daniel. Absolutely, periodicals are a fascinating resource for tracing cultural developments occurring around the time of publication.