‘Dear Mother, Dear Father’: Legation Letters Home

The following guest blog post is by Dr. Andrew Hillier, Honorary Research Associate, University of Bristol.

A trunkful of papers captures the career of a young consular official caught up in the Siege of the Legations, as Dr. Andrew Hillier explains.

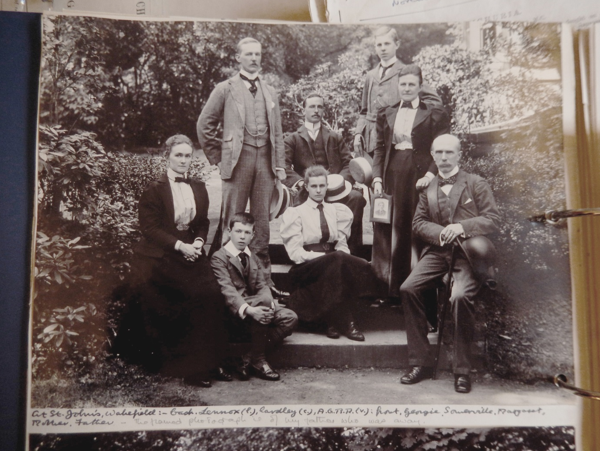

A chance remark – ‘my father was in China’ – was not unusual. Less usual was the follow-up, ‘he was in the Siege of Peking’ (1900). But the story was true and his daughter, Jane Leefe, had a trunkful of papers to prove it.1 Wilmot Peregrine Maitland Russell (1874-1950) had joined the China Consular Service in March 1898 and his parents had kept almost all the letters he had sent home during his first years in Peking (Beijing). Together with press cuttings, journal articles, faded photographs and a few official documents, these highlighted the haphazard and often challenging life for a young consular official at the turn of the century, but, most of all, his heroic conduct during the Siege.

It is unclear why, having come down from Oxford with a good degree, Russell chose to join the China Consular Service. Certainly, there does not seem to have been any family connection. Having passed the entrance examinations, he left England with three fellow- recruits, Phillips, Pearson and Tebbit – all ‘good sorts’ – and, after a brief stay in Shanghai, arrived at the Legation in May 1898. There, as he told his parents, his accommodation was very satisfactory: ‘a first-rate sitting-room with a veranda, a bedroom, bathroom and store-room’. Quickly settling in, having purchased a pony, he would set off for the race course each day at about 4.30 a.m., ‘after a light breakfast’.2

Spending the first two years intensely studying Chinese, he was also able to enjoy the congenial atmosphere of the legation world, playing plenty of sport, making lengthy expeditions into Manchuria, spending long summer days in the temples in the Western Hills and attending Sir Robert Hart’s garden parties. Although he only came fourth in the final examinations in March 1900, having caught the eye of the Minister, Sir Claude MacDonald, Russell was appointed to the Legation’s Chancery, whilst his peers were assigned to the consulates. Three months later, he found himself caught up in the Siege.

Formed into a Volunteer Corps under Sergeant Preston, the Student Interpreters were commended for their ‘pluck and dash, yet steadiness under fire, worthy of veteran troops’, but it was Russell whom MacDonald singled out for his gallantry in one particular incident. Researching the story, I looked online at QUB Special Collections and was lucky enough to find three photographs that perfectly capture Russell’s pluck and dash. They also cry out for more identification.

In both photographs, Russell is instantly recognisable with his trademark hat and jaunty moustache. In the first, he is standing, holding his Martini rifle beside a young boy who is trying to look very serious. Although little is known about the photographs, they would seem to be memento of Customs, Consular and other volunteers, taken soon after the Siege was lifted on 14 August. Multiple copies of the snap-shots exist and they may have been set up by Alphonse Théophile Piry, a French national in the Customs Service, who is standing on Russell’s left (i.e. RHS of photo) wearing a bush hat. It is his son Théo, who is the boy next to Russell. He, his son, Russell and one other seem to be the only ones appearing in both shots.

We can assume this photograph was taken at the same time as it also features Russell, who is sitting on the ground and is in similar garb. The presence of Hart, with his distinctive domed head and greying beard, standing at the left-hand side, suggests these may be mainly members of the Customs staff and their families. In all three photographs, there is a palpable sense of relief that the Siege is over.

On 1 July, 1900, Russell and four Student Interpreters volunteered to join a party of marines in a sortie to seize a gun that the Boxers had placed on the city wall above the Legation and was causing a lot of damage.3 The exercise had been badly-planned and, coming under fire in a narrow lane, several of the men fell, two badly wounded. Taking charge ‘with great coolness’, Russell ordered the rest of the party to shelter behind a projecting wall, whilst he provided cover as the men made their way to safety, two by two, ‘under withering fire’, Townsend being hit through the shoulder and thigh. According to MacDonald, ‘but for Russell’s presence of mind, very few would have survived and had he been eligible, he would have recommended him for the V.C. As it was, Russell had to content himself with the admiration of his peers, two of whose accounts described ‘the death-trap’ they found themselves in and Russell’s ‘remarkable courage’ and ‘level-headedness’.4

5. British Students’ Corps. From left to right, back, J.G. Hancock, C.A.W. Rose, H. Porter, H.A.J. Flaherty, C.C.A. Kirke, H. Bristow, W.E. Townsend (wounded, on crutches), Front, L.H.R. Barr, Russell, R.G. Drury. W.M. Hewlett and L. Giles. H. Warren had been killed on 16 July. The public school jauntiness masks the frightening ordeal they had gone through. The photograph in its Chinese wooden frame is proudly displayed in Russell’s daughter’s home. Apart from Russell, none of these seem to be in the three photographs above. Private Collection, copyright reserved.

In his letters home and a series of articles written many years later, Russell described his experiences both in the Siege and its aftermath when he was engaged in policing the city, hunting down suspected Boxers and presiding over their summary and, at times, brutal execution.

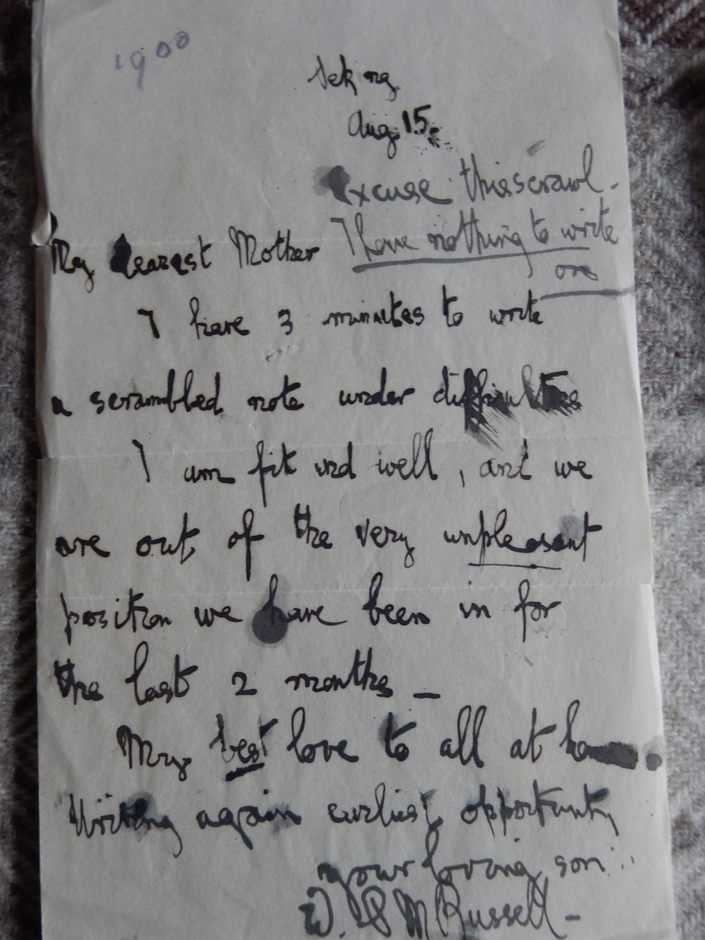

Whilst this is told in graphic detail, nothing better captures the tension and relief than his first scrawled note, written the day after the arrival of British troops under General Gaselee on 14 August 1900.

Having spent a further two years in Peking, he was then assigned to a range of treaty ports, including Chungking (Chongqing), where he was acting Consul (1906) and Shanghai (1907).5

Towards the end of 1908, he was instructed to open a vice-consulate at the coastal port of Antung (Dandong) which lay 300 kilometres south of the riverine port of Mukden (Shenyang), to which it had been recently connected by railroad. Delayed by the Russo-Japanese War which had devastated the surrounding countryside, the Customs House had been opened in March 1907. The aim of the consulate was to keep an eye on increasing Japanese influence in the region and encourage British merchants to exploit its rich forests, ‘the apple of discord between Russia and Japan’, as Russell described them.6

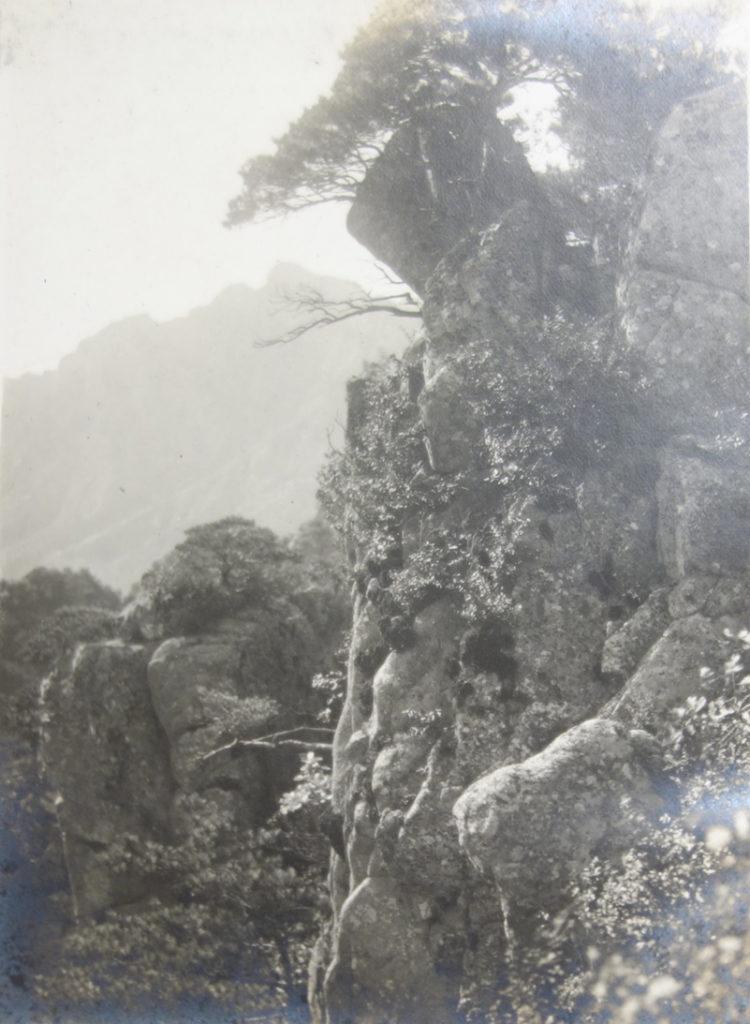

Keen to impress, he prepared detailed reports on the region and trading prospects and, in February 1908, set off for Mao’er Shan, where Lao Pai Shan, the Old White Mountain, rises to 8000 feet. Completing the journey in a month, he covered some 600 miles by pony.7 However, although the climate was healthy, if intensely cold, the accommodation in Antun was basic in the extreme and seriously unsanitary. Within fifteen months, he was suffering from severe dysentery. Granted six months home leave, he left China in February 1909. He would never return.

Arriving in England, he applied to join the General Consular Service, arguing that he could not go back to China, both because of his own health and because he was about to get married. Although the application was strongly supported by Macdonald and his successor, Sir Ernest Satow, it was turned down. Eventually, the Foreign Office acceded to his application for ill-health retirement and, in February 1910, awarded him a pension of £164/16/8 p.a. Later that year, despite the expanding timber trade, the consulate was permanently closed on account of the unsanitary conditions.8

There is a sense that, for all its hardship and trauma, including the death of a number of colleagues, Russell found it difficult in his later consular career to match the excitement of the Siege and the camaraderie of Legation life. Although the occasional expedition broke the monotony, being holed-up in a remote and inhospitable out-port was no life for someone so enthusiastic and ambitious and keen for action and adventure. Four years later, with his health restored, he would again have that opportunity. Serving with the Gordon Highlanders, he fought at Gallipoli and on the Western Front and, again, distinguished himself, winning the Military Cross.9

His first marriage did not work out and, having obtained a divorce, he eventually re- married in 1932, this time to Amy Moncrieff Penney. Their daughter, Jane, was born two years later; only sixteen years old when he died in 1950, she asked her father little about his time in China but she clearly remembers being told how he was reluctantly forced into eating his own pony during the Siege, and how he retained a fascination for the country and the time he spent there. Now, with the help of his own papers and photographs and material that can be found in other collections, more than a hundred years later, she is able to piece together this phase of his eventful life.

1 I am very grateful to Jane Leefe for all her enthusiastic help and for allowing me to study and draw on her father’s papers.

2 Various letters from Wilmot Russell to his father and mother.

3 The incident is described by MacDonald in his Report from Her Majesty’s Minister in China in respect of Events in Peking, China No.4, p.58 and also in a Minute of Private Secretary, 10 August 1909, TNA FO 369/269, written when Russell was applying for ill-health retirement; Russell also described the events in two articles, ‘The Defence of the Peking Legations: A Retrospect’ and ‘The Occupation of Peking by the Allies after the Siege of the Legations in 1900’, National Review (1926), pp. 386-405 and 742-755.

4 Leslie R. Marchant (ed.), Lancelot Giles, The Siege of the Peking Legations: A Diary (Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press, 1970), pp. 137-138, W. Meyrick Hewlett, The Siege of the Legations June to August 1900 (Harrow, Editors of the Harrovian, 1900), p. 29.

5 Chungking was one of the most un-prepossessing ports: see P.D. Coates, China Consuls (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 306-312.

6 Robert Nield, China’s Foreign Places: the Foreign presence in China in the Treaty Port Era, 1840-1943 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015), pp. 37-39, Capt. Wilmot P.M. Russell, M.C., ‘Manchuria’, Chambers’ Journal, 1937, p. 741.

7 Report of a Journey from Antung to Maoershan, enclosed in letter to Sir John Jordan, 14 April 1908, TNA, FO 228/1693.

8 TNA, FO 369/269 and FO 369/282.

9 Foreign Office List, 1932.

Photograph no. 5 above is of personal interest as J.G. Hancock- back row, far left, was my grandmother’s eldest brother. Justinian George Hancock from Lambeth, London, U.K. was the eldest of 9 children. He died from typhoid fever shortly after the end of the legation siege. His parents received a posthumous award of the China medal, and a plaque was placed in St Marks church, Kennington in memory of those from the service who died in the siege.

13 years later in 1913 his 2 younger sisters and their husbands went out to live in China at the French legation in Shanghai, where my mother was born in 1919.

Anne, our apologies for the great delay in replying.

Thank you so much for your comment. How interesting to hear that you have a family connection to someone in the 5th photo!

Hi Ann

I’ve only just seen your v. interesting reply! (I’m the writer of the blog). I would be very interested to hear more about your family in China- do you have any papers or photographs relating to that time? I am a Research Associate at Bristol University & am extremely interested in the stories of British families in China.

Incredibly I am the grandson of Elsie Hancock, one of those two younger sisters!

I have just been writing a history of our side of the family, and I feel sure your grandmother, who I assume to be Jessie and your mother, who I assume to be Eileen, would have visited my relatives at 177 the Peak, Hong Kong where they lived. if you would like to find out more, just email me at; ruddjones@btinternet.com. My mother Joan is still alive, aged 95.

William Meyrick Hewlett was my grandfather! Sadly I don’t remember him as I was a baby when he died

Richenda, many thanks for your comment. It is lovely to hear from relatives of people noted in our collections and blog posts.

Hi Richenda

good to hear from you. Might you have any papers or photoghaphs relating to his time in China?

Hi Andrew, nice of you to respond. Sadly my answer is no I don’t have anything, other than some coloured photos of the Summer Palace. My father was his younger son & I am led to believe that all his papers etc went to his elder son.

Thanks- shame!