“Hillier called…”: A Glimpse at Sir Robert Hart’s Papers in Special Collections, Queen’s University, Belfast

About the author:

Andrew Hillier is a mature student at the University of Bristol, having spent most of his career as a practising barrister. He hopes that his Ph.D. is nearing completion.

We’re very grateful to our guest blogger, Andrew, for his generosity in writing this post about his research project and wish him every success in his upcoming viva

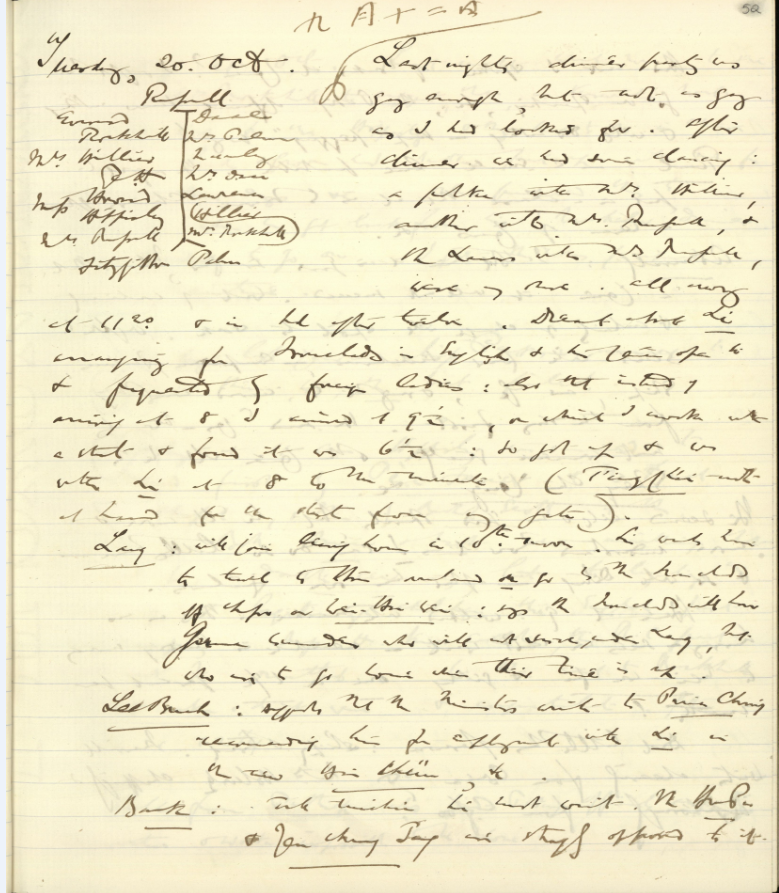

QUB MS 15.6.1.B7

Much has been written about Sir Robert Hart, who held the position of Inspector-General (IG) of the Chinese Maritime Customs (CMC) from 1863 until his death in 1911, at the age of 76, but no attempt has been made to write a comprehensive biography. Whilst this may seem surprising, given that he was without doubt the most influential Westerner in nineteenth century China, it is understandable when the enormity of the task is considered, both for the biographer and for those who would have to read the resulting work. It is also, I think fortunate, because it would be extremely difficult to convey the character of the IG in the way it emerges from reading his papers. For long, the best source for this has been his correspondence, most especially, the two volumes of letters written to his London agent, James Duncan Campbell.

However, as the painstaking process of deciphering his spidery writing continues at QUB, a further accessible source is beginning to emerge. Saved from the fire which destroyed most of his papers during the Boxer Uprising (1900), the diaries comprise seventy-seven volumes, covering the years, 1854 to 1908. Of these, two composite volumes (1 to 4 and 5 to 8) take it up to 1866 and, together with volume 31 (1885), are available on-line, volumes 13 to 18 have been transcribed and volume 19 is in progress. For the remainder, however, there is no alternative but to sit in the comfort and calm of the Special Collections Reading Room and work through the manuscripts. I recently spent several days carrying out this, at times exasperating but ultimately rewarding, exercise and, whilst alcohol was essential at the end of the day, it paid dividends for my research.

My PhD (which I am undertaking at Bristol University under Professor Robert Bickers) is concerned with the relationship between family and empire, which I am exploring through the lens of various forbears who lived and worked in China and Southeast Asia in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Of these, three brothers – Walter, Harry and Guy Hillier – knew Hart well and worked closely with him over some forty years, in, respectively, the consular and diplomatic service, the CMC and the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (as it was then called).

By chance, as mentioned above, Jennifer Regan has transcribed Hart’s diary for 1885. This had already whetted my appetite as there were descriptions of his meetings with Walter Hillier, who had just been appointed Chinese Secretary at the Legation, and with Guy Hillier, who had been despatched by the Bank to explore the possibility of opening an agency in Peking. However, whilst there were plenty of entries covering their work, the real interest for me in this volume lay in the social side of Hart’s life. A keen ‘ladies man’, he took a shine to Walter Hillier’s wife, Clare, whom he found ‘very pretty’ and whose extrovert personality lit up the routine life of Peking’s Western society and, in particular, his dinner parties. Having already despatched his wife and children to England, Hart attached great importance to these occasions, which normally consisted of his entertaining anything between eight and sixteen guests. His diary, complete with table plan, would record the success or otherwise of the evening as we see in the entry for 12 September 1885, from which the transcriber’s task is also self-evident. For present purposes, the following is sufficient:

Tuesday, 20 Oct. [Chinese characters:] “12th September” Russell [Everard?] Daae Rockhill Mrs Palm Mrs Hillier [?] R.H. Mrs [?] Miss Honsard Lawrence Hippisley Hillier Mrs Russell Mrs Rockhill Fitzgibbon Palm

Last night’s dinner party was gay enough, but not so gay as I had looked for. After dinner we had some dancing: a polka with Mrs Hillier, another with Mrs Russell, and the Lancers with Mrs Russell, were my share. All away at 11.20, and in bed after twelve. Dreamt about Li arranging for Ironclads in English and the Yamen open to and frequented by foreign ladies: also that instead of arriving at 8 I arrived at 9 ½, on which I woke with a start and found it was 6 ½ : so got up and was with Li at 8 to the minute. (T’ing Chen not at hand for the start from my gate).

QUB MS 15.1.31.52

What we glean from this and subsequent entries is how much Hart enjoyed his music and dancing. Here he danced the Polka with Clare – on another occasion, he records her giving him ‘a waltz lesson which went fairly well for a first lesson – she said’[1]and a few weeks later, he is calling on her and making friends with her two children –‘the little boy is a fine wee man’ and lending her his horse, Ben Hur.[2]

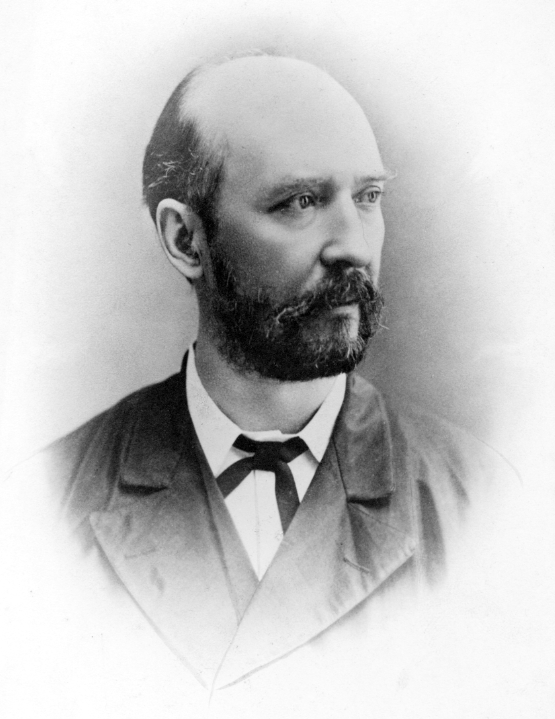

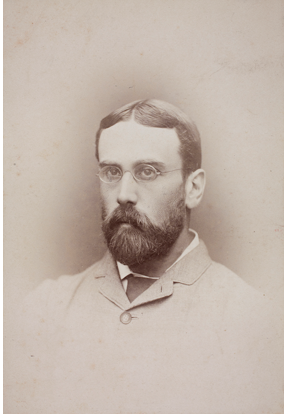

Hillier Collection

Hart’s relationship with Clare was exactly what he relished, mildly flirtatious without any risk of it going further and here, and in many similar entries, we can see the very human side of someone often perceived to be a dry and austere Ulsterman. These entries thus provide an invaluable source for understanding the intimate life of Peking and the important role a consular wife could fulfil in that constrained milieu. It was fortunate, indeed, that this particular volume had already been transcribed and this encouraged me to undertake the formidable task of trying to read the diaries for myself in order to understand Hart’s working relationship with the Hillier brothers.

For my visit, I had limited myself principally to three years – 1897 to 1899 – , during which Guy and his elder brother, Harry, worked closely with Hart in connection with two significant events affecting Sino-British relations. The first concerned the negotiation of the third tranche of the Loan which China required in order to fund the Sino-Japanese Indemnity, following her defeat in the War (1894-1895), and the second related to Britain’s acquisition of the New Territories and its impact on the CMC.

As the Peking Agent of the Hongkong Bank, Guy Hillier had conducted the Indemnity loan negotiations on behalf of the Bank from the outset. In the event, the first tranche had been won by a Franco- Russian Consortium and the second by the Bank (along with the Deutsch Asiatische Bank, DAB) but only with Hart’s assistance. In respect of the third tranche, therefore, there was all to play for.

Beginning in September 1897, numerous diary entries, prefaced with the phrase, ‘Hillier called’, describe the tortuous negotiations and the way in which Hart and Guy Hillier, working in tandem, dealt with both the Legation and Chinese officialdom. The entry for 25 December 1897 (QUB MS 15/1/51/121) reads ‘Hillier says Bank can’t float loans without help of Germany, France & Belgium! .. I must [?] try what [Y – possibly a name?] can do’. By February, 1898, the DAB had agreed draft terms. The entry for 19 February 1898 reads ‘Hillier came round & co-signed the preparatory agreement for sixteen million sterling loan. I wrote to Lian (for Chang) …likin will not do & this must be found’ (QUB MS 15/1/51/181).

Hillier Collection

But along with these entries, we have this touching personal reflection for Sunday 20 February 1898 (QUB MS 15/1/52/1):

….today I begin my 64th year. I am old but in my ways young and it is wonderful how clear my mind is and how free from pain my body … but my memory is not what it was and my strength & activity are disappearing. Birthday gifts & cards from various people and places.

Finally, on 1 March, “the 2 loans agreements are arranged this am ((8 @ 10 ½ ): [? ?] English version for Hillier & [R?] & arranged that if French [? appear /approve] we’ll say their desire for [?] [?] be [?revised] [?Loan] & supported, but agreement must be signed.’ (QUB MS 15/1/52/13)

These events are described in Stanley Wright’s Hart and the Chinese Customs pp. 663 -666, but, even with the difficulties of transcription, it is only through the diaries that we are able to capture their immediacy and the brinkmanship involved. They are also invaluable for highlighting Guy Hillier’s role and the way he and Hart were working together in their dealings with other officials, European and Chinese.

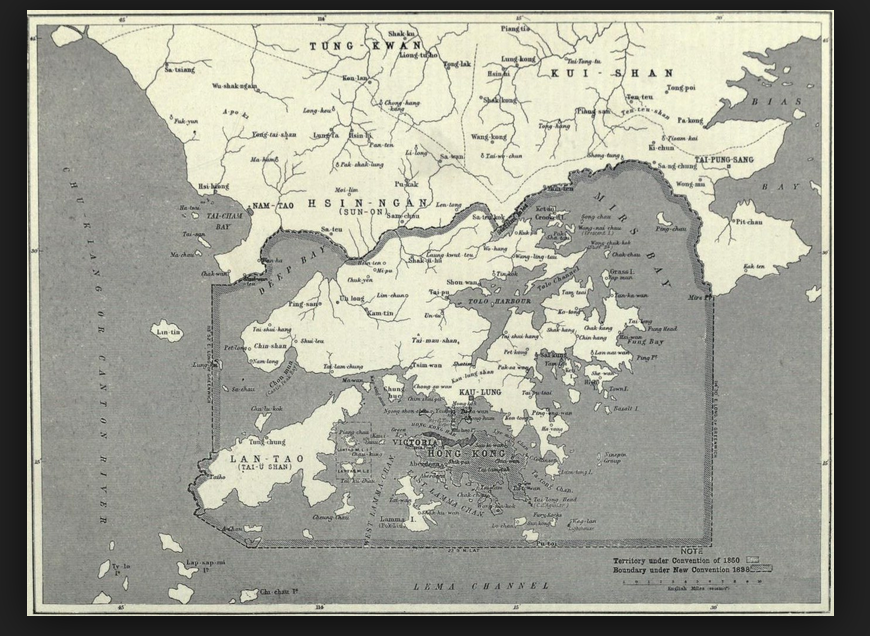

At the same time, the Western powers saw China’s defeat in the War as an opportunity for seizing control of territory beyond the treaty ports. As part of this scramble, pressure mounted on the British government to secure sufficient of the mainland immediately north of Hong Kong to provide better security for the Crown Colony. This necessarily entailed removal of the Customs stations positioned along the coastline and, against Hart’s wishes, the CMC were moved unceremoniously ‘bag and baggage’ out of the area. Incensed at the way this was handled, which included significant loss of life, when the local people resisted, the Chinese officials complained that Harry Hillier had not done enough as the Kowloon Commissioner to protect their interests. Whilst there was plenty of evidence that Harry could not have done more to resist British aggression – in particular, he had argued that the Customs Station could have been re-positioned in Kowloon City – I was interested to see what the diary said about his involvement.

It was clear from his entries that Hart had supported Harry but, as he wrote on 22 April 1899, ‘if Viceroy will not see Hillier, what are we to do?’(15/1/54/129). On 4 May, he decided there was no alternative and wrote, ‘I am immediately transferring Hillier to Shanghai after 2 leaves & moving King to Kowloon’. By chance, the following day Guy Hillier called and introduced Tom Jackson, the esteemed manager of the Hongkong Bank, and on 7 May, the Jacksons and Guy were amongst Hart’s dinner guests, and, as he afterwards noted, ‘dinner and dance went off exceeding well’ (15/1/54/144).

Whilst these events could have been ominous for Harry Hillier’s career, it is clear that Guy was able to tell Hart that his brother was keen to have a break and thus through this family network, what could have been a difficult situation was smoothed over, with Harry being appointed to the prestigious role of Chief-Secretary to the IG in Shanghai on his return. However, this only took place after the Boxer Uprising, during which Harry was out of the country. Amongst Hart’s papers in the Special Collections is a clutch of letters from well-wishers following the Uprising (in which Hart was at one point reputed to have been killed) and I wondered whether there might be any from Harry. To my delight, there was a letter dated 28 September 1900, sent from Lausanne, where he and the family were spending his leave. Addressed to ‘Sir Robert’, it also captures their relationship and, responding to the news that his leave had been extended by a couple of months, he writes, ‘I should have preferred to have returned to China at the expiry of my original leave. An idle life at home is not so easy to endure when such sterling events are taking place in China’ (15/2/1/4).

It was no easy task to get on well with Hart and secure his confidence and, through these sources, I had been able to measure his relationship with each of the brothers, Walter, Guy and Harry, in terms of both their work and their more intimate lives, and the important part this played in furthering their careers. I had achieved my goal but, before leaving, there was just time to glance briefly at the marvellous photographs in the Collection, many of which reflect Hart’s busy social life. Again, I was lucky.

QUB MS 15.6 Part 9

Here was a typical photograph of one of Hart’s garden parties. As usual, he is wearing his bowler hat and, further to his left, Guy Hillier is sitting in a cane chair, looking somewhat stern and older than his fifty years. But, by this time, he had completely lost his sight and, an austere man at the best of times, garden parties may not have been his favourite past-time. By this stage, he and Hart had been working together for some twenty years and this shot captures the mix of public and private life in Peking’s small Western milieu.

The Hart papers therefore are a rich source for understanding the day to day dynamics of Sino-British relations during this period, how nuanced that relationship was and how much British officials, such as the Hillier brothers, relied on Hart for advice in their dealings with the Chinese. They also convey the relish with which Hart responded and performed that role. Painstaking though it is, the task of deciphering the diaries is ultimately rewarding. As the transcripts emerge and they become more accessible, they will provide an invaluable picture of the complexity and sensitivity of the IG and the way in which he was able to exercise such a dominant position in Sino-British relations. Perhaps, when that task is complete, someone will be tempted to embark on the formidable task of writing a comprehensive biography.

Andrew Hillier

May 2016

[2] 9 February 1886. (MS 15/1/31/192)

[1] 25 November 1885. (MS 15/1/31/95)

Congratulations on your successful struggles with Hart’s writing. Fid you find any leters from the Hillier ladies at Queen’s?

May Tiffen

Hi Mary,

Thanks for your comment! We’ll pass your query re. the Hillier ladies on to Andrew. Best wishes, SC&A Team