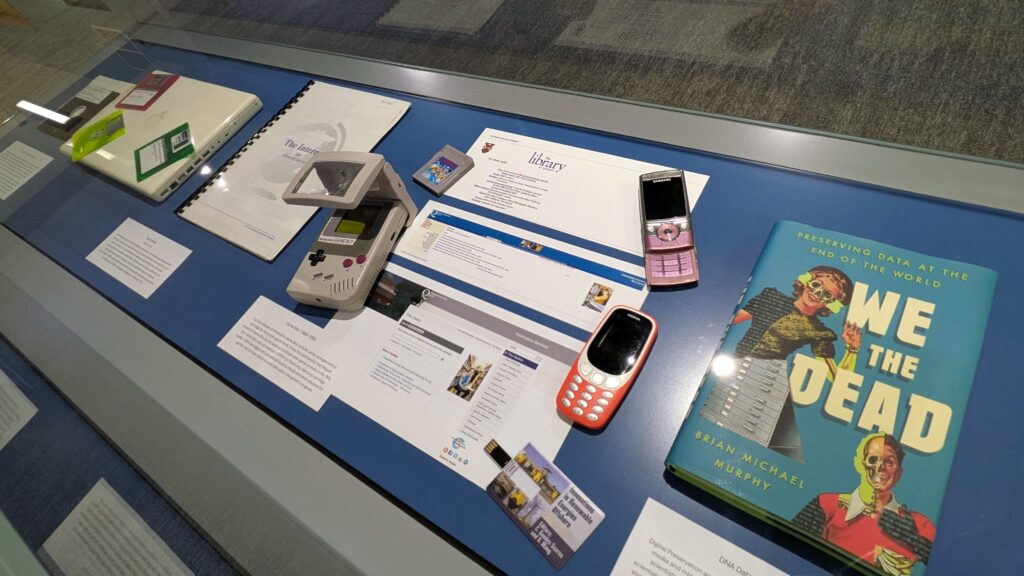

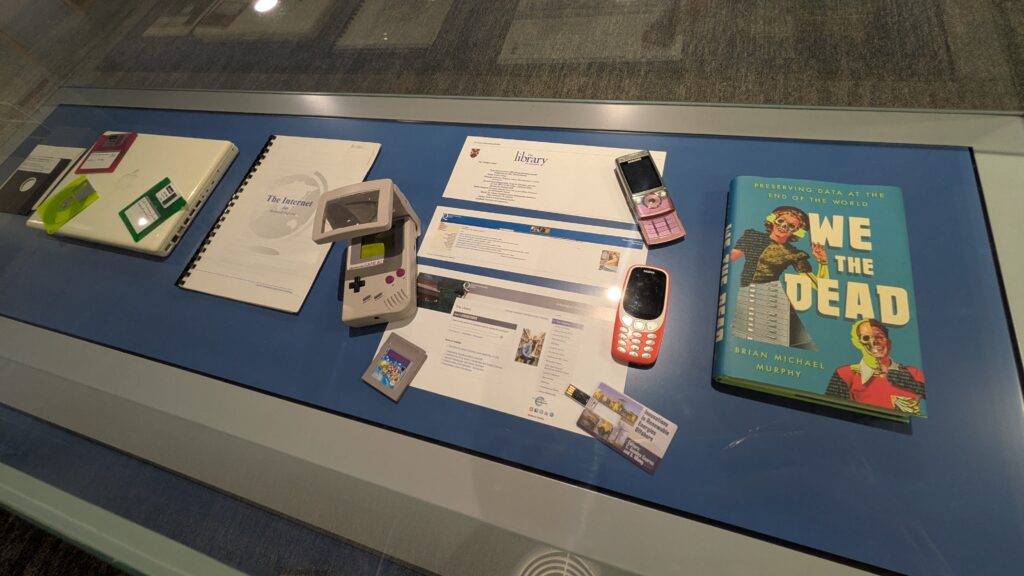

Exhibition: A “Digital Graveyard” of Obsolete Media

Queen’s Special Collections & Archives prepared a “Digital Graveyard” in November, exhibiting obsolete media formats once commonly used at Queen’s University. This exhibition launched on World Digital Preservation Day, an annual celebration led by the Digital Preservation Coalition, and will continue in the Floor 1 display cases at the McClay Library until 23rd January 2026.

Why Digital Preservation Matters

Over time technologies evolve; media is replaced by smaller, more portable alternatives; software is updated; and data becomes unreachable as specialist file formats and the technologies designed to read them are decommissioned. As a result, materials saved on digital media could become lost or inaccessible without active intervention.

Digital Preservation helps us to mitigate the impact of media obsolescence over time. Some Computer Museums do this by preserving the physical media along with the hardware and software needed to read it, or by “emulating” the original environment needed to play media files. Another option is to use a migration-based strategy to plan and actively maintain the data held on the media files. We can do this through a number of approaches, from refreshing media carriers, to migrating older formats to more up-to-date versions, and taking action to remedy or replace files at the first signs of corruption. This helps digital files to weather changing technologies, so they can continue to be accessed beyond the life of their original media carriers.

Obsolete Media at Queen’s

The Digital Graveyard exhibition explores the history and use of data storage media at Queen’s from the 1960s onwards. From punch cards to floppy disks, the changing shape of digital media over time reminds us of the inevitability of technological obsolescence. A video cassette or a digital audio tape, becomes little more than a plastic shell without the equipment to read the data contained within. Below, we explore selected media from the archive, which are considered obsolete today; their data unreachable, without equipment that was once ubiquitous, but is now rare.

All media have a suicide pact. The pattern repeats. Excitement. Ownership. Decline. Denial. Decay. Disposal. Death. At the moment of release, media are dying.

Tara Brabazon, 2013

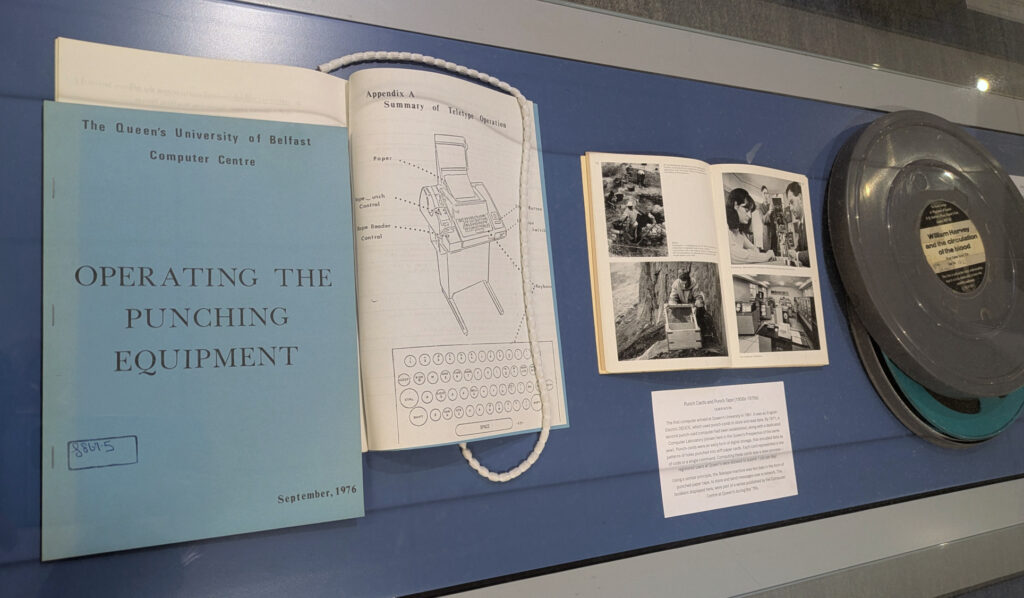

Punch Cards and Punch Tape (1950s-1970s)

QUB/E/4/2/36

The first computer arrived at Queen’s University in 1961. It was an English Electric DEUCE, which used punch-cards to store and read data. By 1971, a second punch-card computer had been established, along with a dedicated Computer Laboratory (shown here, from the Queen’s Prospectus of the same year). Punch-cards were an early form of digital storage, that encoded data as patterns of holes punched into stiff paper cards. Each card represented a line of code or a single command, and the physical process of submitting these sequentially and waiting for individual jobs to be read meant that computing was a slow process—to manage this, registered users at Queen’s were allowed to submit just one job per day!

Using a similar principle, the Teletype machine, illustrated in the booklet above left, was fed data in the form of punched paper tape, to store and send messages over a network. These early forms of data storage were susceptible to damage from creases or bends in the punch cards, and file integrity could be compromised by disarranged or misplaced cards, which affected the machine’s ability to read them correctly. Although transformative for complex processing and networked data transmission, the shortcomings of punch card technologies simultaneously inspired their replacement, as demand grew for more efficient means of encoding information.

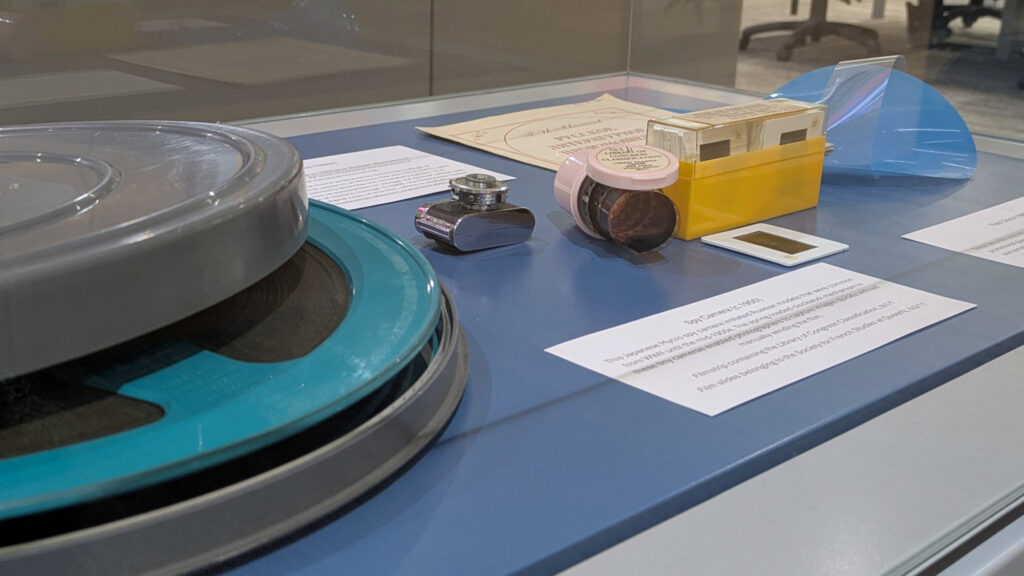

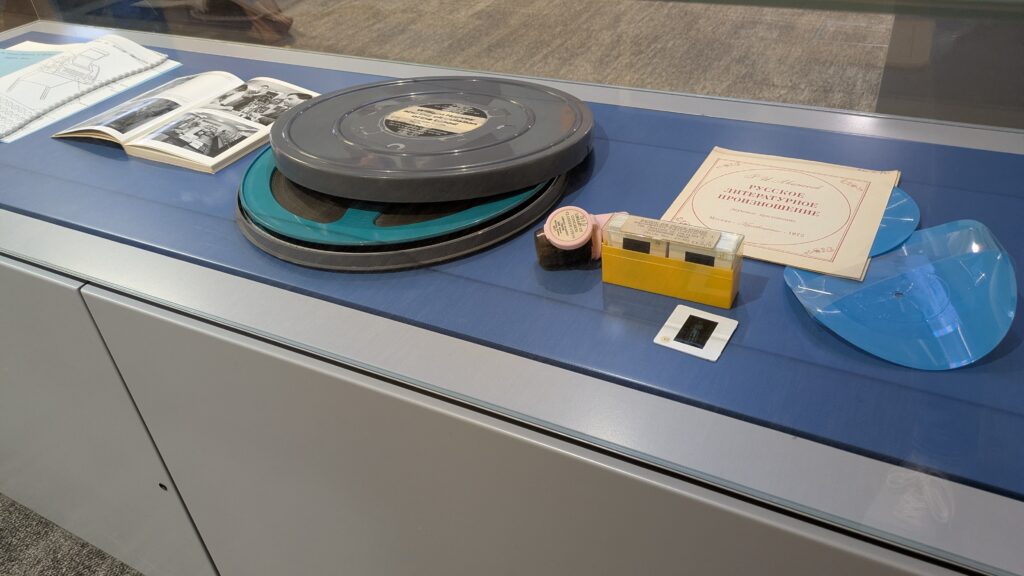

16mm Film (1920s-1980s)

Advances in visual media provided new teaching opportunities. The adoption of 16mm film was an accessible and affordable alternative to the traditional 35mm cinema standard introduced by Kodak in 1923, enabling educators to integrate motion picture demonstrations and documentaries into the lecture theatres.

The film reel visible below left, was an educational movie produced by the Royal College of Physicians, 1971. It explores the research of William Harvey (1578-1657), who was the first person to correctly describe the circulatory system. Unfortunately, the cellulose in reels such as this, is susceptible to ‘vinegar syndrome’, where the pungent release of acetic acid causes the film to warp and breakdown, sometimes leading to irrecoverable loss of historic footage. Digitising film can help preserve its contents, ensuring they remain accessible, while reducing the risk of wear-and-tear to the physical reels. The Wellcome Collection have preserved a digital copy of this educational film, which is available to watch online at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/y683v77d

Flexi Discs (1960s-1980s)

Rec C/21

Towards the late twentieth century, media became progressively smaller and more portable. This was transformational for learning, as scholarly texts could be supplemented with visual or audio counterparts. For example, ultra-thin vinyl records, were often distributed in magazines and books, or as promotional giveaways, their bendable design meaning they could be discreetly inserted into publications. This record (above, right) was an audio supplement to Ruben Avanesov’s 1972 book, “Русское литературное произношение / Russian Literary Pronunciation”, a significant work in Russian phonetics and phonology. The text and illustrated diagrams in the book were demonstrated by the accompanying audio flexi disc; a common addition to language publications, which particularly supported the audiolingual method and facilitated home practice.

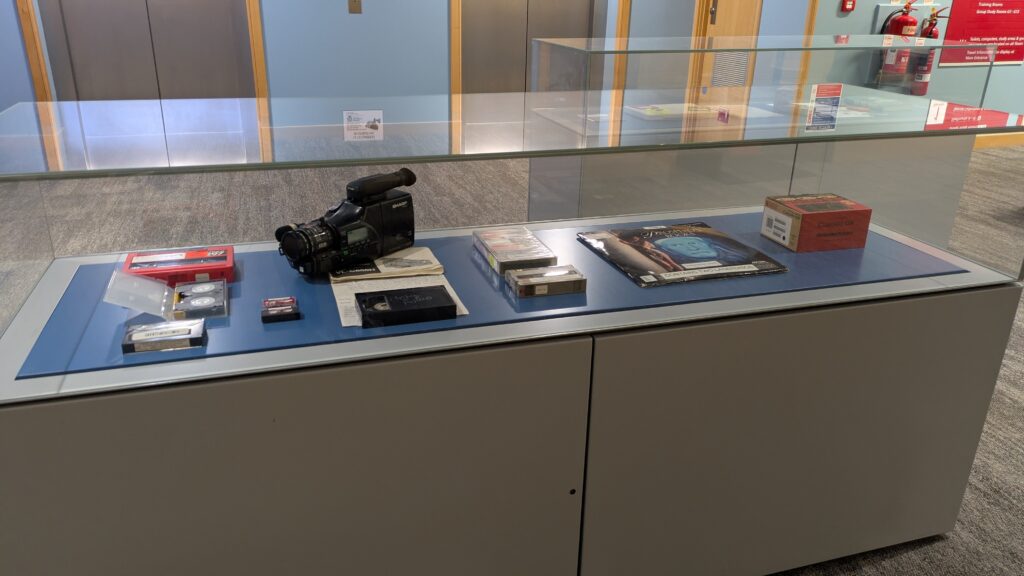

Tape Media (1970s-1990s)

The arrival of magnetic tape formats accelerated this trend. Not only did storage media become smaller and more portable over time, but the introduction of technologies like the Compact Audio Cassettes, invented in the early ‘60s by Philips, had a widespread cultural impact by democratising personal recording and enabling listeners to consume, mix, and share audio outside the fixed environment of the library or classroom.

Academic staff at Queen’s later adopted digital tape formats such as like Digital Audio Tape (DAT) or digital video tapes like DVCPRO, for recording teaching material, which extended the role of portable media for pedagogy, and enabled an early form of blended learning.

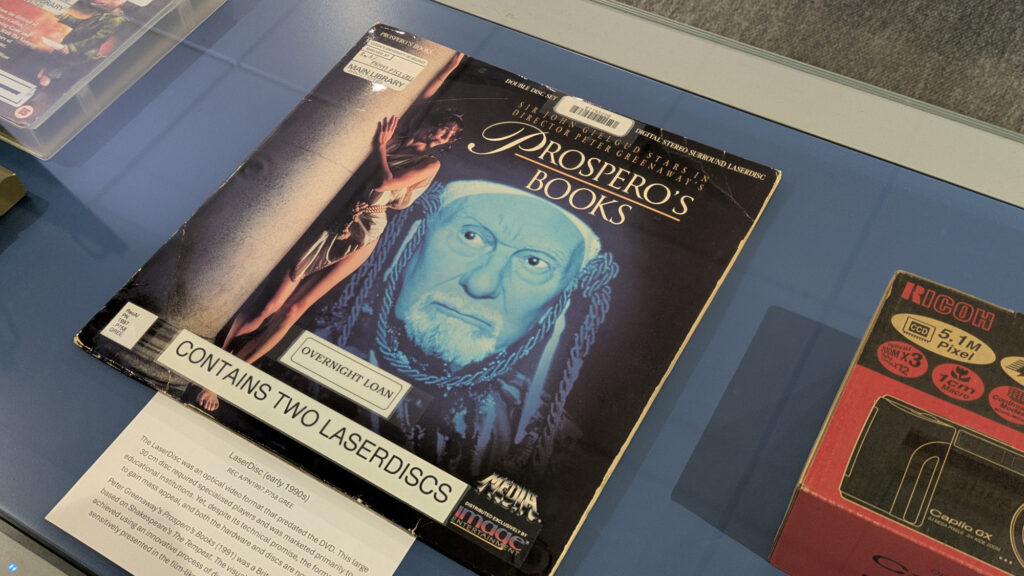

Laserdisc (early 1990s)

Rec A/ PN1997.P758 GREE

As storage media evolved, they reshaped how content was experienced. The Laserdisc was an optical video format that predated the DVD. This large 30 cm disc required specialised players and was marketed primarily to educational institutions, promising cinematic quality to enhance educational programming. Yet, despite its technical promise, the format failed to gain mass appeal, and both the hardware and discs are now extremely rare.

The Laserdisc of Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books (1991) is a last example a Laserdisc uncovered in the holdings at the McClay Library. Prospero’s Books was a British avant-garde film based on William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. The visual effects in the film, were achieved using an innovative process of digital layering, which was more sensitively presented in the film-like image of the experimental Laserdisc medium.

Digital Camera (early 2000s)

At the turn of the noughties, the popularisation of digital cameras, enabled creative freedom to instantly review, delete, and share images stored on compact flash cards and SD (Secure Digital) media. These solid-state memory cards revolutionized portable data storage, holding vast numbers of high-resolution photographs in a pocket-sized format, and facilitating new forms of visual documentation. Yet, despite their speed and efficiency, flash cards were often at risk of sudden failure or corruption from static discharge reversing the electrical charge of the ‘bits’.

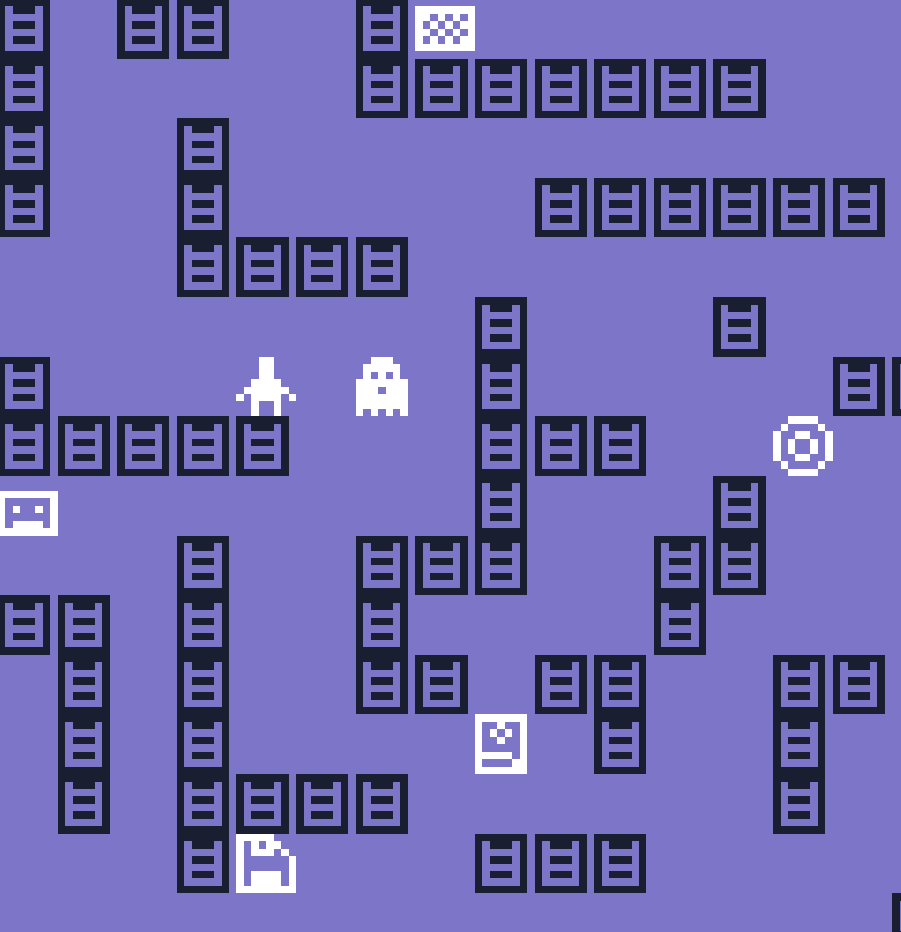

To learn more about obsolete media formats, try our Digital Graveyard Game!

“In the far future, bits of hard drives may be fossilized in limestone, and discarded iPhones may find themselves encased in amber, hardened like nail polish, but the bits of humanity that these exquisitely crafted machines hold will be lost to time.”

Trevor Paglan, 2012, cited in

Brian Murphy, We the Dead, 2022

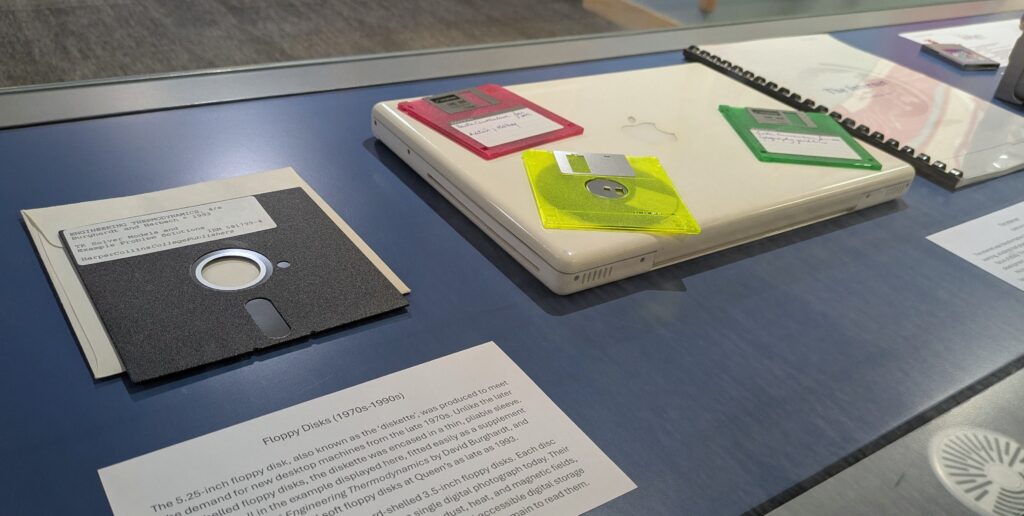

Floppy Disks (1970s-1990s)

TJ265 BURG

Fig 7. Diskette supplement to Engineering Thermodynamics (4ed.) by David Burghardt and James A Harbach, 1993; and examples of floppy disks and Apple MacBook issued to Queen’s staff in 2006.

Floppy disks marked another turning point for computing. The 5.25-inch floppy disk, also known as the ‘diskette’, or even the ‘minifloppy’, was produced to meet the demand for new desktop machines from the late 1970s. The first floppy disks were encased in a thin, pliable sleeve. The soft shell in the example displayed here, fitted easily as a supplement into the 4th ed of Engineering Thermodynamics by David Burghardt and James A Harbach. It contained example models and solutions for scholars to practice with, and shows the use of soft floppy disks at Queen’s as late as 1993.

These were later replaced by hard-shelled 3.5-inch floppy disks. Each disk held only a few megabytes—less than a single digital photograph today. Their magnetic surfaces were easily corrupted by dust, heat, and magnetic fields, making floppies unreliable by today’s standards. These disks were revolutionary in that they provided accessible digital storage for personal computing, enabling students and academics to store and transport their own work with ease, however today, few drives remain to read them.

The Internet

QUB/E/4/2/36

The final shift represented in our Digital Graveyard is perhaps the most transformative: the arrival of the internet signalled a shift in education by facilitating individualized learning and equipping students with greater choice than ever before for directing their own focus of study. The instructional booklet visible in Fig 8 is a key artefact from the early development of the World Wide Web. Queen’s were an early subscriber to Microsoft, and Internet Explorer, one of the earliest browser software, which launched in 1995, was readily accessible to students as part of the Windows 95 Plus! package installed on University PCs.

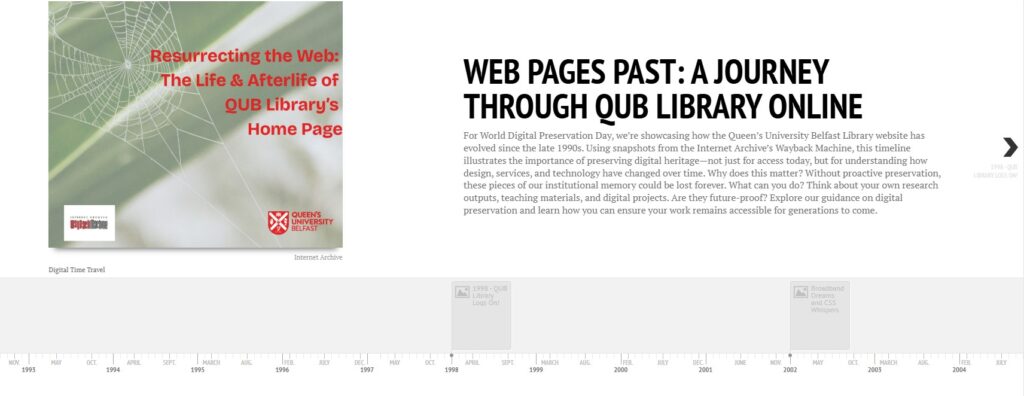

A Timeline of QUB Library Webpages

The Library at Queen’s embraced the internet as a tool for scholarly access with the launch of its first webpage in 1998. What began as a sparse HTML site with a form for proposing books, gradually expanded into a sophisticated research ecosystem of databases, catalogues, and curated digital resources. Students were no longer reliant on physical catalogues or fixed library hours; instead, networked information became an extension of personal computing itself.

Digital preservation isn’t just about safeguarding individual files—it is also important to maintain the context that gives those files meaning. Websites are a perfect example: they evolve over time, reflecting changes in technology, design trends, and user needs. Without preservation, these transformations can be lost, leaving gaps in our institutional memory. To illustrate this, we’ve created an interactive timeline showcasing the evolution of Queen’s University Library’s webpages from 1998 to the present day. Click on the timeline below, to see key milestones, design changes, and the progression of digital services that have shaped the online experience for students and researchers over nearly three decades.

DNA Data Storage (2022-)

These obsolete media serve as a reminder that knowledge is never entirely secure in its material form. It must be continually monitored, refreshed, and migrated to more robust or up-to-date formats. The technologies that once promised permanence now populate our digital graveyards, but they also tell a story of continuous reinvention. Today scientists are developing the next enduring storage medium; from data storage in living bacteria, to the return of the punch card concept with perforated DNA (Murphy, 2022). Wandering through the digital graveyard exhibition, we ask ourselves, what will be added to the digital graveyard of the future?

Bibliography

Amidon, A. (2020) Film Preservation 101: Why does this film smell like vinegar? [Blog] The National Archives: Unwritten Record. Available: https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2020/06/19/film-preservation-101-why-does-this-film-smell-like-vinegar/

Brabazon, T. (2013) “Dead Media: Obsolescence and Redundancy in Media History.” First Monday, 18(7). Available: https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i7.4466

Cochrane, E. (2024) “Obsolescence”, Digital Preservation: A Critical Vocabulary [Preprint]. Available: https://digital-preservation-a-critical-vocabulary.pubpub.org/pub/ajzjdqk4

(1971-72) William Harvey and the circulation of the blood. Source: Wellcome Collection: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/y683v77d

Murphy, B. M. (2022) We the Dead: Preserving Data at the End of the World. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press

Curtis, J. Museum of Obsolete Media. Available at: https://obsoletemedia.org/ (Accessed: November 2025).

I have really enjoyed reading this article and reliving all the different stages of development of the technology. As a music teacher I remember making audio loops with classes on open reel tapes in 1971. Later commissioning wind band scores with DAT tape electronic sounds for School wind band and also a commission for a composition for jazz band and electronic tape. Today trying to perform a Stockhausen composition for live players and tape must be a nightmare because there are no cues on the tape, so if you get out of sequence, you have to start again at the beginning. In the future it will be a real problem to access this material and I don’t see the kind of revival happening that we saw in the 1960, with early music instruments being built and people specialising in Renaissance or Baroque performances. What I think is sad, is for example the time teachers have spent learning how to programme these different technologies. So I spent hours learning Flash and building music teaching resources for use with interactive white boards, and then overnight Flash was obsolete.

Thanks for the great comment, Keith—it’s interesting to hear your experience of these technologies and how the changes impacted on methods and culture of music production and education!