“Read all about it!” Notes on an Annotated 18th Century Newspaper Collection at Armagh Public Library

Dr Michael O’Connor of QUB Special Collections reflects on an idiosyncratic Eighteenth-Century Newspaper Collection

Recently, I had the good fortune to be invited by Armagh Public Library to visit and consult their eighteenth-century Irish newspaper collection. I had the pleasure of meeting the Dean of Armagh, the very Reverend Gregory Dunstan and staff at the Library, including Carol Conlin, and I’m very grateful for the hospitality and assistance I received during an extremely memorable visit. My thanks are also due to Dr. Sally Montgomery for arranging this in the first instance. Aside from their unfailing graciousness, the visit proved especially significant since I had the opportunity to peruse a seldom consulted, but rather considerable, treasure of Irish printed newspapers.

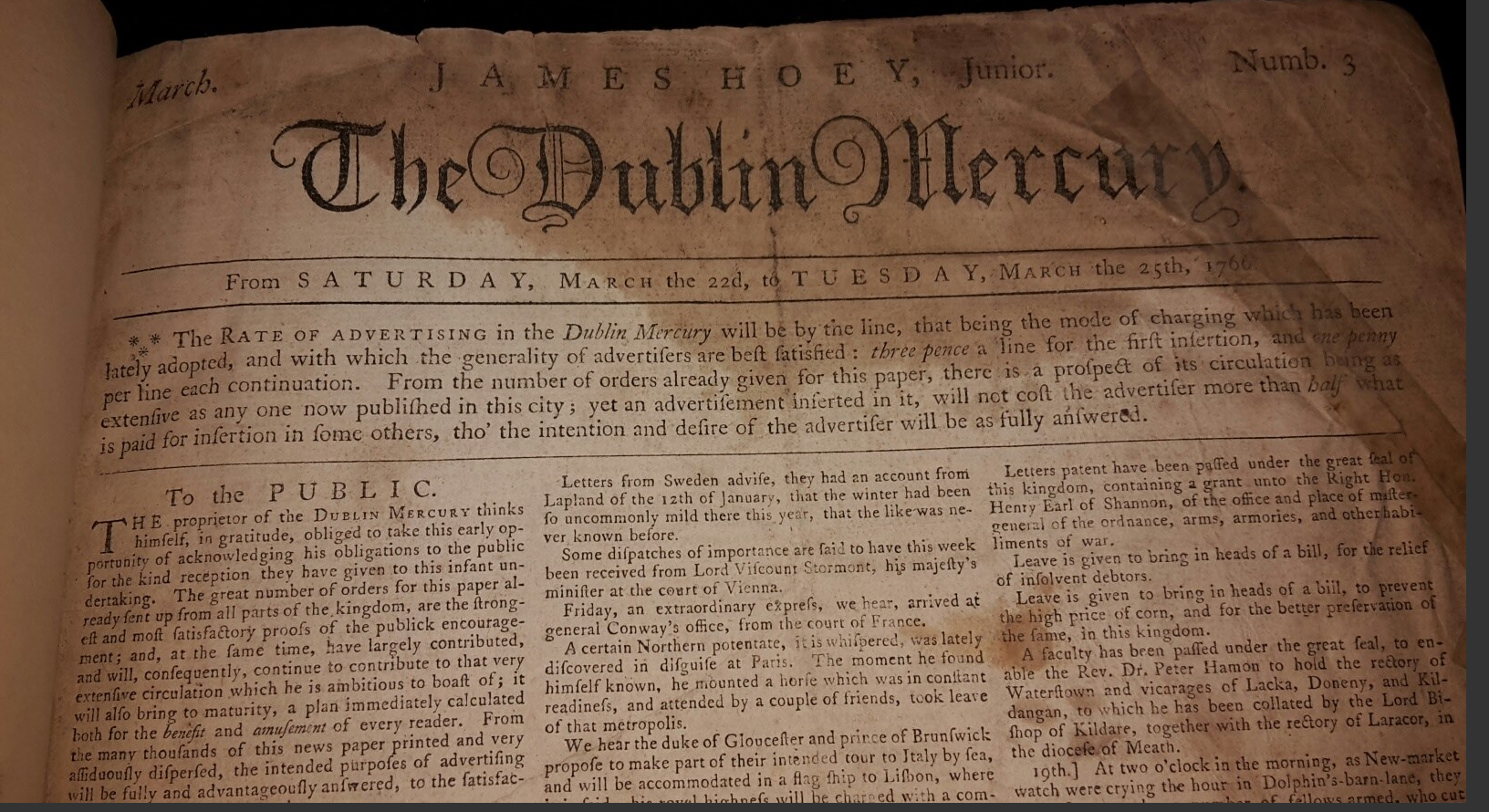

The Library is blessed in its holdings of an appealing assortment of newspapers spanning the eighteenth century. Many of the titles are Dublin titles; this is hardly surprising owing to the importance of Dublin as a print centre – dynamic and fertile in terms of its published output throughout the early modern period particularly. As a result the Library holds titles such as The Dublin Evening Post, The Dublin Journal, The Dublin Gazette and The Dublin Mercury. These newspapers will be of obvious interest to scholars of the eighteenth-century period and those investigating Dublin as a print and news hub.

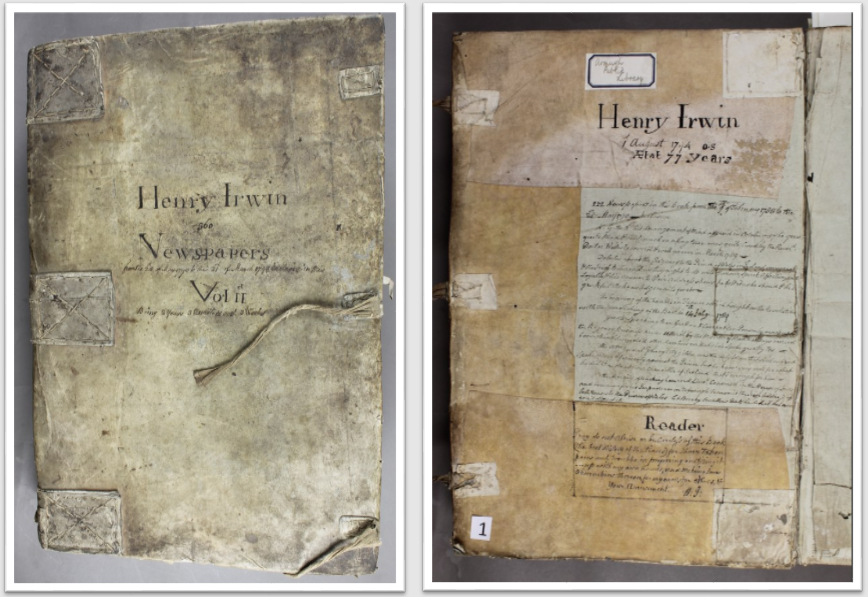

Most notable, however, among the eighteenth-century newspaper holdings is the Henry Irwin collection. Substantial – both in terms of significance and volume – it is an impressive scrapbook collection that is both thrilling and captivating; it has the potential to enthral all who examine its hefty tomes. It is in remarkably good condition also and cannot fail but astonish, amuse, and interest by its beguiling singularity and the sheer breath of newspaper topics included.

Most notable, however, among the eighteenth-century newspaper holdings is the Henry Irwin collection. Substantial – both in terms of significance and volume – it is an impressive scrapbook collection that is both thrilling and captivating; it has the potential to enthral all who examine its hefty tomes. It is in remarkably good condition also and cannot fail but astonish, amuse, and interest by its beguiling singularity and the sheer breath of newspaper topics included.

It is evident that the eponymous collector, Irwin (b. 1717) had a fascination with events and newspapers of that period since he amassed, collected and arranged eighteenth-century newspapers in his own personal collection. The collection comprises 6 volumes, 16 newspaper titles and approximately 2200 issues. Irwin’s 6 volume scrapbooks include the following newspaper titles:

- Dublin Evening Post

- The Morning Post: or Dublin Courant

- Magee’s Weekly Packet

- Evening Herald

- The Public Register, or Freeman’s Journal

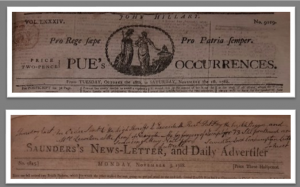

- Pue’s Occurrences * [Not available NLI. Available TCD]

- Saunder’s News-letter and Daily Advertiser * [Not available NLI. Available TCD]

- The Times (London)

- The Town: Dublin Evening Packet

- Lloyd’s Evening Post

- The Evening Herald; or, General Advertiser * [Not available NLI. Available TCD]

- Dublin: The Universal Advertiser

- The Rights of Irishmen: or National Evening Star * [Not available NLI. Available TCD]

- The Public Register, or Freeman’s Journal

- Dublin News-letter

- Dublin Gazette

While some of the above titles are not recorded in English Short Title Catalogue, all these newspapers are available in National Library of Ireland or Trinity College Dublin.

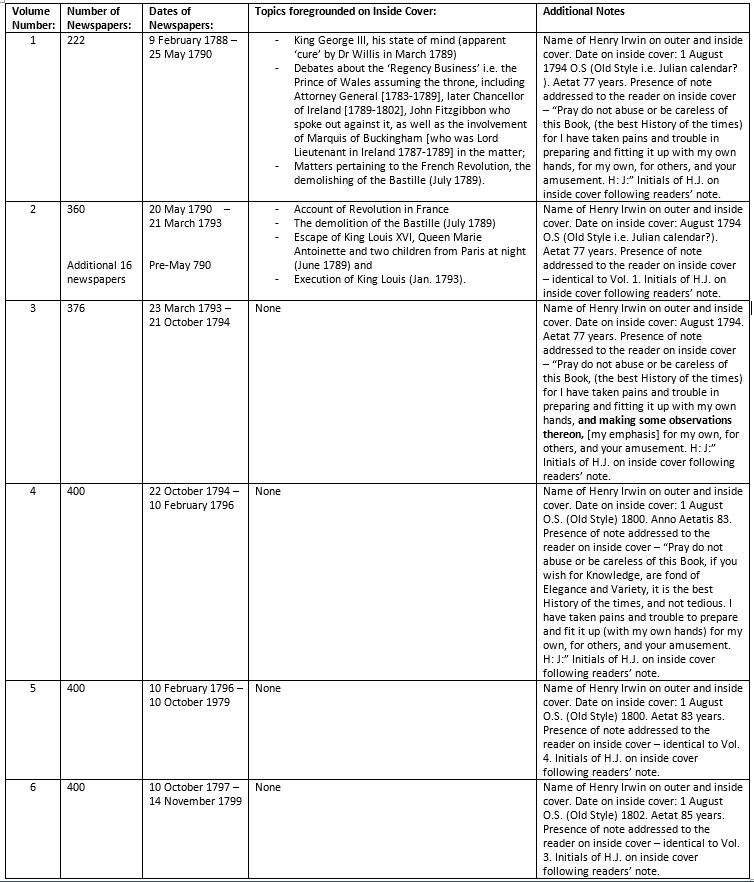

Each volume is covered with a rudimentary and inelegant but perfectly functioning leather binding. Each volume is prefaced with autographed notes from Irwin. This includes date information, the number of newspapers contained within each volume, the topics foregrounded at the outset of each volumes and additional notes, including notes to the reader. I have captured this information and include in the grid below:

Who was Henry Irwin?

Unfortunately, very little is known about Henry Irwin. As the compiler of the scrapbooks, his name, initials, handwriting and signature feature in the volumes; his age is also provided at the outset of each volume. He is recorded as 77 years old in volumes 1-3, 83 years old in volumes 4 & 5, and 85 years old in volume 6. This means that Irwin would have been born in 1717 and was still alive in 1802, the date of the last volume. Some of the handwritten notes on the inside cover of Vol. 1 (dated 1790) confirm that the compilation of the scrapbook was contemporaneous with the publication dates of the newspapers contained therein. For example, Irwin makes reference to John Fitzgibbon as “now Chancellor of Ireland.” This was a position Fitzgibbon held 1789-1802.

Our best source of information about Henry Irwin is the collection itself. Without question, he was a newsprint aficionado. The heavily annotated scrapbook collection attests to his evident passion for compiling and commenting on news, and his annotations reveal a man of strong emotions and imposing personality.

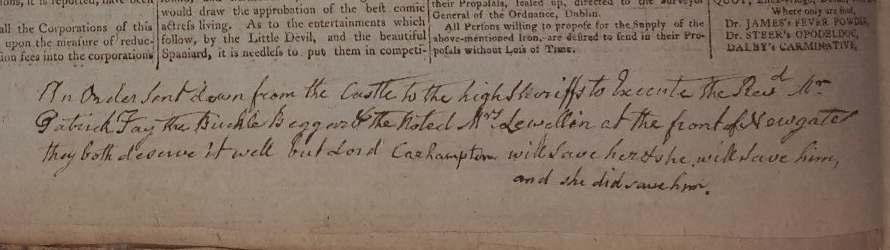

His annotations could be humorous, mordant or, indeed, excessively censorious. For example, he denounces the loss of an estate in Meath by an individual, the result, Irwin posits, of “youthful Extravagance” and he comments on the fate of a man who is sentenced to hang at Newgate, a fate he regards as befitting – he “deserve[s] it well.” He notes that “Billy Pitt [is] audacious [.] I wish I had hold of him [.] I’d cure his ambition if I cou’d.”

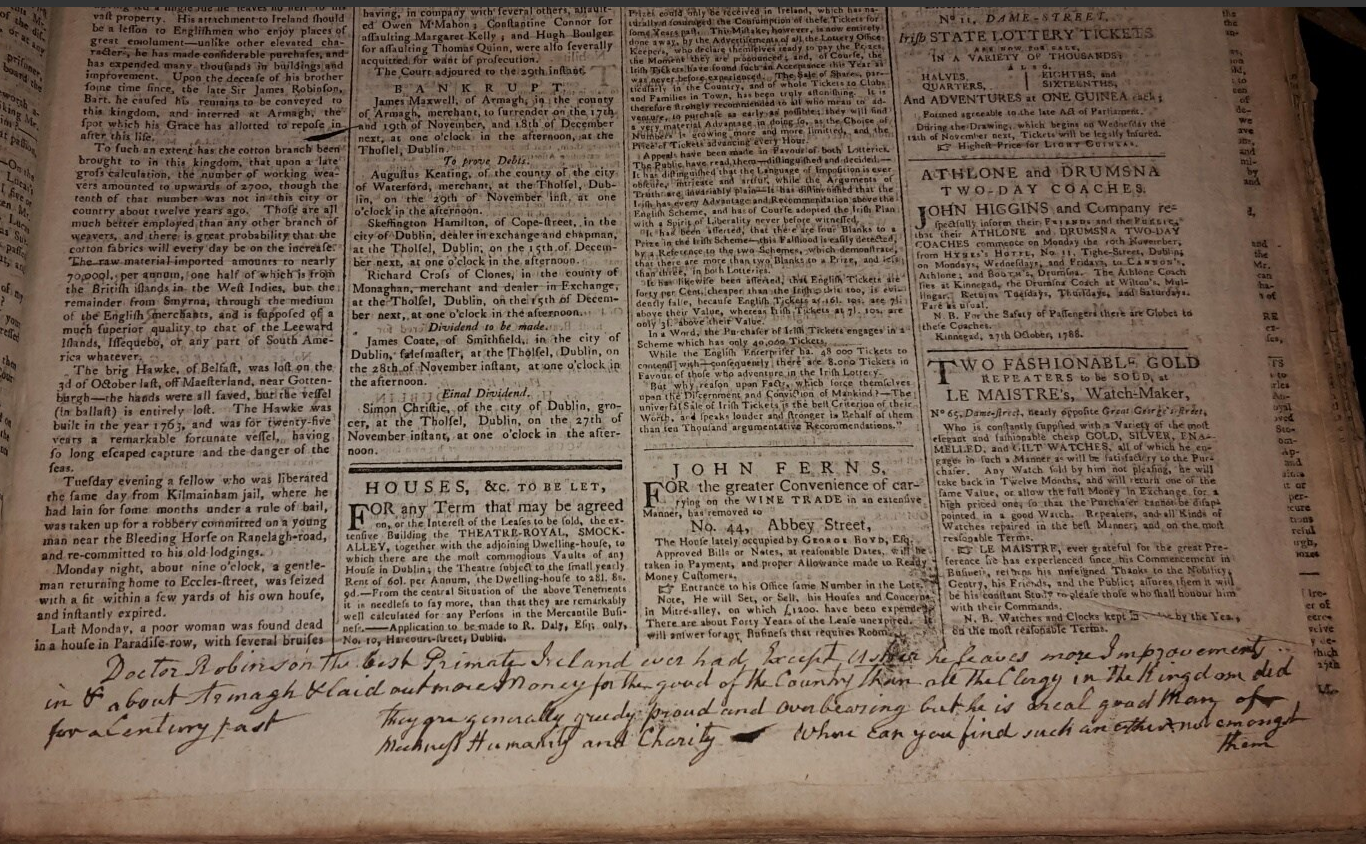

He was also however capable of delivering praise and admiration. In November 1788, he cites “Doctor Robinson” as

[T]he best Primate Ireland ever had Except Usher [.] He leaves more Improvement in & about Armagh & laid out more money for the good of the country than all the clergy in the kingdom did for a century past [.] They are generally greedy [,] proud and overbearing [,] but he is a real good man of meekness [,] humanity and charity – where can you find such another& not amongst them.

The unrestricted nature of his annotation is part of the fascination of this collection. These annotations – some are very forthright and peremptory – may suggest that they were possibly circulated to a ‘private’ circle of family and very close friends, those who shared Irwin’s views, or, at the very least, understood Irwin’s indomitable character. Beyond that circle of friends and well-wishers, one imagines that his comments could have jarred and provoked ire. One could argue, however, that perhaps his comments were expressly designed to challenge and that the sometimes excoriating nature of his annotations do not preclude circulation to a readership beyond family, confidants and close friends.

While there is further work needed to establish the finer detail concerning the circulation and readers of the collection, a number of core facts can be established. The presence of a note addressed to the reader in each volume evidences that the volumes were circulated to his contemporaries, and that they were designed to amuse. Irwin asks of his readers that they “do not abuse or be careless of this Book, (the best History of the times) for I have taken pains and trouble in preparing and fitting it up with my own hands, for my own, for others, and your amusement.” The absence, moreover of pecuniary information in relation to circulation suggests strongly that this was not a commercial enterprise.

Appeal of Irwin’s Newspapers:

Irwin’s collection is compelling for two main reasons. Firstly, Irwin organised the material into volumes which are arranged chronologically. Issues are arranged by date and not grouped together by newspaper title. This permits the reader to compare and contrast news items across a specific time period from different newspapers. Secondly, Irwin’s annotations provide a unique insight into one contemporary reader’s response to significant national and international events. For example, he comments on the mental health of King George III, the French Revolution, the Fall of the Bastille and other pertinent news items of the late eighteenth century. It is thus the intersection of his comments with the printed news items which provide the real charm of the collection since it betrays Irwin’s biases and interpretation, and reveals much about him as ‘newsman’ and collector.

The collection is ultimately a valuable resource of untapped intertextuality, waiting to be explored by potential researchers. The sheer volume of the printed collection (approximately 8000 pages of newspaper content), coupled with the intriguing handwritten annotations, provides wonderful material for prospective researchers across a range of disciplines and for those more generally interested in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.