Commemorating Black Histories of Intellectual Resistance

Guest blog by Prof Dina Zoe Belluigi

It is timely to commemorate histories of the acts and enactors of intellectual resistance. Dread is tangible within academic communities across the world, many of which are witnessing or experiencing repressive attacks and operating within oppressive conditions. These are being exerted to stifle the critical thought of those expressing dissent against injustice. Reminders are needed of the complicated historical relation of freedom to academic freedom, and of the many traditions of resistance from which to learn and grow in fortitude, for the present.

This extended visual essay re-minds through commemoration of those who worked within ‘the university’ to counter the raciological ordering of the world, and to resist its intersections with patriarchy.

Figure 1 The subject of this image is the folded corner of a page in a chapter by Vanessa Holford Diana (2007) on Black women intellectual’s “narrative patterns of resistance”, marking something of importance to a QUB reader. Within the text pictured, are references to ‘white men’, lawfare and US institutions. (Photo: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast)

During the month of October 2025, there will a display of items on the first floor of the McClay Library that speak to intellectual resistance. They have been selected from the Main Library and Special Collections & Archives, Queen’s University Belfast (QUB). Black History Month (BHM) in the United Kingdom (UK) and in Ireland is celebrated in October. In 2025, the UK BHM theme is “Standing Firm in Power and Pride”, while Ireland’s theme is “Celebrating our Sisters, Saluting our Sisters, and Honouring Matriarchs of Movements”. As you will read below, both these themes framed my selection for the display.

While activities within QUB this year include talks on Black British and Black Irish thinkers and doers, the display I’ve curated focuses on the writing of two dissenters – W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) and Bantu Steve Biko (1946-1977). They were rejected by those in power: the US citizen Du Bois was made stateless; Biko was tortured and killed by South Africa State Security agents. However, their selection is particularly because of their relation to academic agency within ‘the university’. Both Du Bois and Biko addressed academic citizens through their writing about the plight of people well beyond academia. Attempts were made to sanction, censor and erase their scholarship from circulation, within and beyond, academia. Yet both faced discrimination against their person within academia. Alongside a selection of their work held at our Library, I have set books which are reclamations of women intellectuals’ life and thought in the USA and South Africa in the 20th Century.

Commemoration as remembrance

Du Bois was a strong supporter of public pedagogy for historic consciousness. Concerned about propaganda as amnesiac within USA’s national narratives and formal education systems, he supported the original idea of a month to raise consciousness of Black resistance (Sinitiere, 2016). This subject is made apparent in his last resting place, the home gifted to him in Ghana as a refuge by the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, which is now the W. E. B. Du Bois Centre. Floor-to-ceiling posters within that Centre commemorate his role in Black History Month.

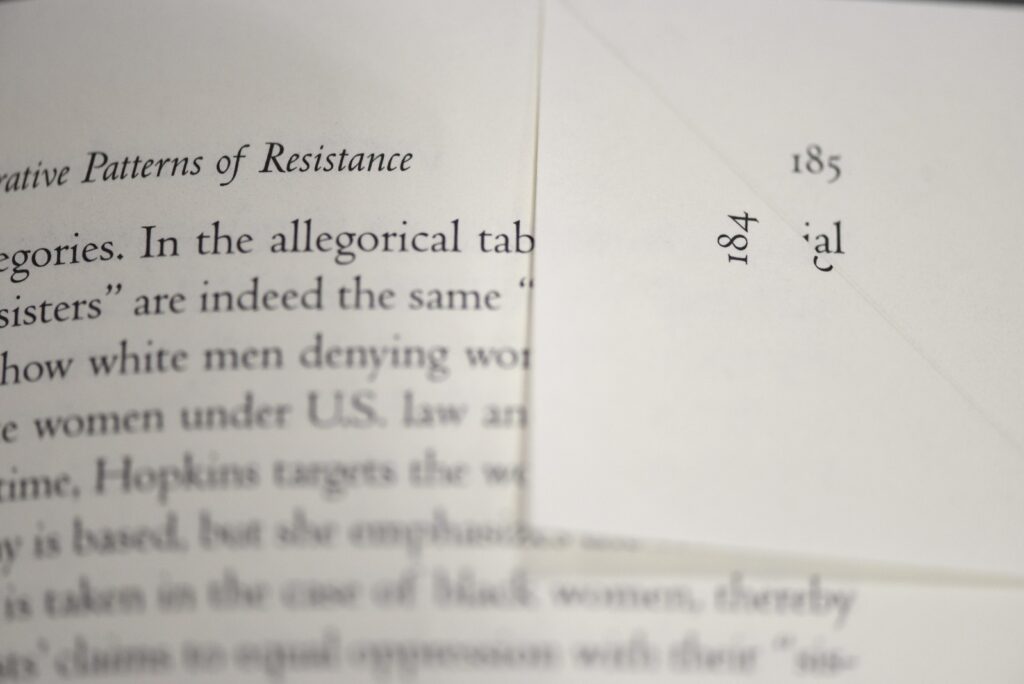

The second major focus of commemoration is his writing. His intact personal library displays some of the many volumes he produced – on Black flourishing – to counter problematic myths circulating about inferior ‘races’. Older, threadbare manuscripts are in vitrines (Figure 2), in addition to his diaries.

Figure 2 One of the manuscripts on display at the W. E. B. Du Bois Centre was his copy of ‘The Suppression of the African slave-trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870 (Photo: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2023, Accra). The edition we have at QUB Library has an introduction by the formidable historian Saidiya Hartman. She has written powerfully on the lives of women in the decades after abolition, and their representation within archives generally, including visuals particularly.

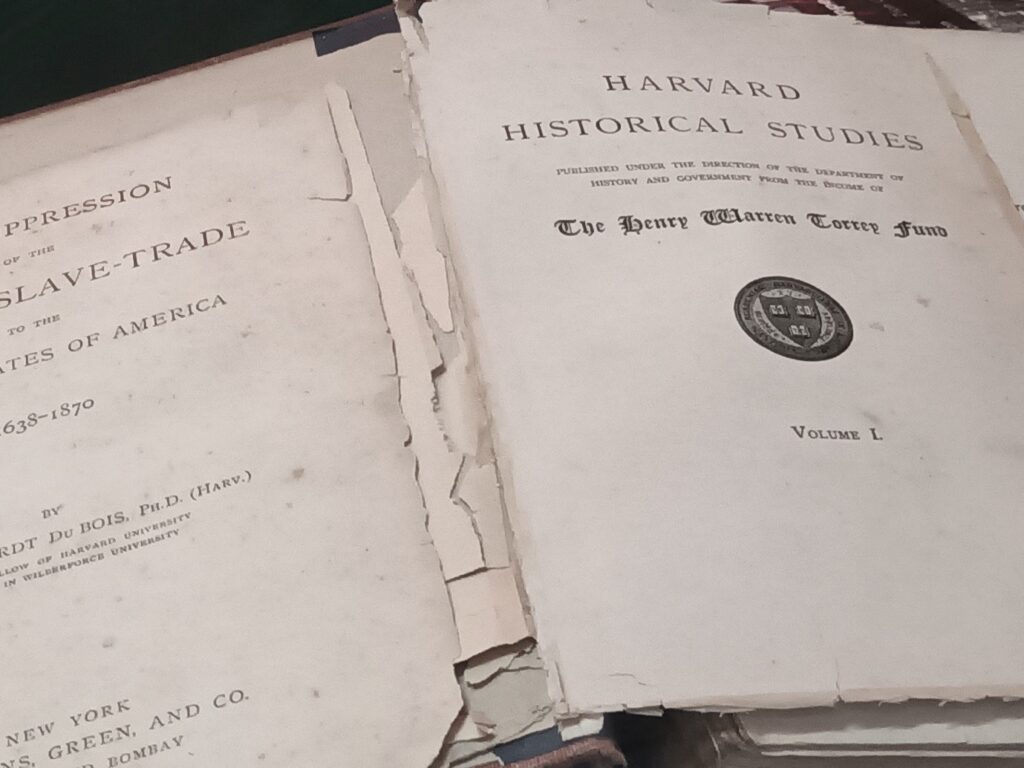

Du Bois’ scholarship is comprehensive and significant – researching and writing prolifically against racism in the USA, and those oppressed within the colonies of the time. In the display at McClay are a selection of the dozens of titles that the Library holds, including The Gift of Black Folk, Africa and his autobiography. What I find compelling about the latter, as a person who studies universities, is how he foregrounds the impact that various institutions had on his life – both predominantly Black institutions, and those predominantly ‘white’ (Figure 3). Similarly, so much about his life as an academic citizen features in the Ghanian Centre – from formal signs of his prestige, such as his academic dress, qualifications and publications and the sub-cultures of belonging, such as the fraternities to which he belonged. Alumni, to this day, place wreathes in his honour there, around his memorial stone.

Figure 3 From a selection of the books by Du Bois on display in QUB Library (left), is a detail of the content’s page of The Autobiography of W. E. B. Du Bois (right), which features a number of universities. Du Bois was the first African American to graduate from Harvard, one of the institutions he writes about in his autobiography. That was in 1895. I raise it specifically because that institution only got around to (briefly) electing its first Black president in 2023, Claudine Grey; after which a backlash of lawfare ensued. (Photos: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast)

What is also poignantly apparent in the Ghanian Centre, is the contrast between Du Bois’ recognition within Black Studies, Africana Studies and much Sociology on the African continent (Al-Hardan, 2022) – and the attempts to erase his legacy as one of the founders of US Sociology from the EuroAmerican canon (Guy & Brookfield, 2009; Morris, 2015).

Commemoration against erasure

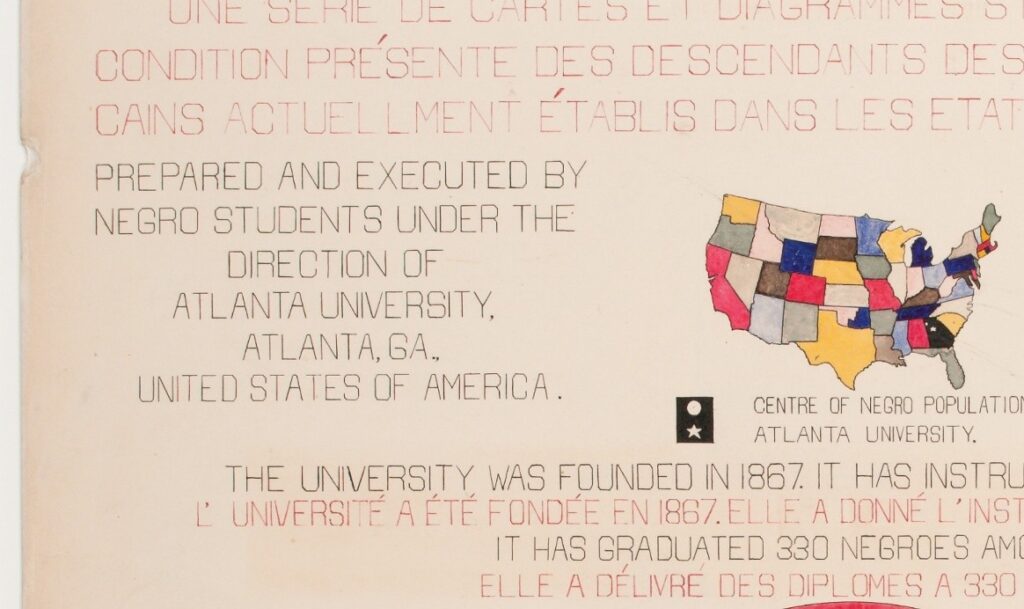

Within the one display case, I have focused on reproductions of graphs and figures which were composed by hand. These are fascinating, and rather beautiful productions that until recently had been hidden away from public knowledge, and thought lost. They were originally produced as part of the 1900 exhibition in Paris for a display about African Americans, which had been curated and erected by African American intellectuals, including Du Bois. At the time he was what we would now call an ‘early career academic’.

The materials that were compiled for the exhibition included visualisations of economic, demographic, and sociological data which projected images of social progress and development, to challenge ideas of weakness or inferiority, including those of eugenics. These were visualisations of what Du Bois termed ‘the colour line’, which conceptually are “a nexus of competing gazes in which racialization is understood as the effect of both intense scrutiny and obfuscation under a white supremacist gaze” (Smith, 2004, 2).

Figure 4 In the detail of ‘‘A series of statistical charts illustrating the condition of the descendants of former African slaves now in residence in the United States of America’ one sees the words “Prepared and executed by Negro students under the direction of Atlanta University”. Here, and in other data portraits selected for the display, are examples of Du Bois’ re-assertion of the intellect and academic flourishing of African Americans.

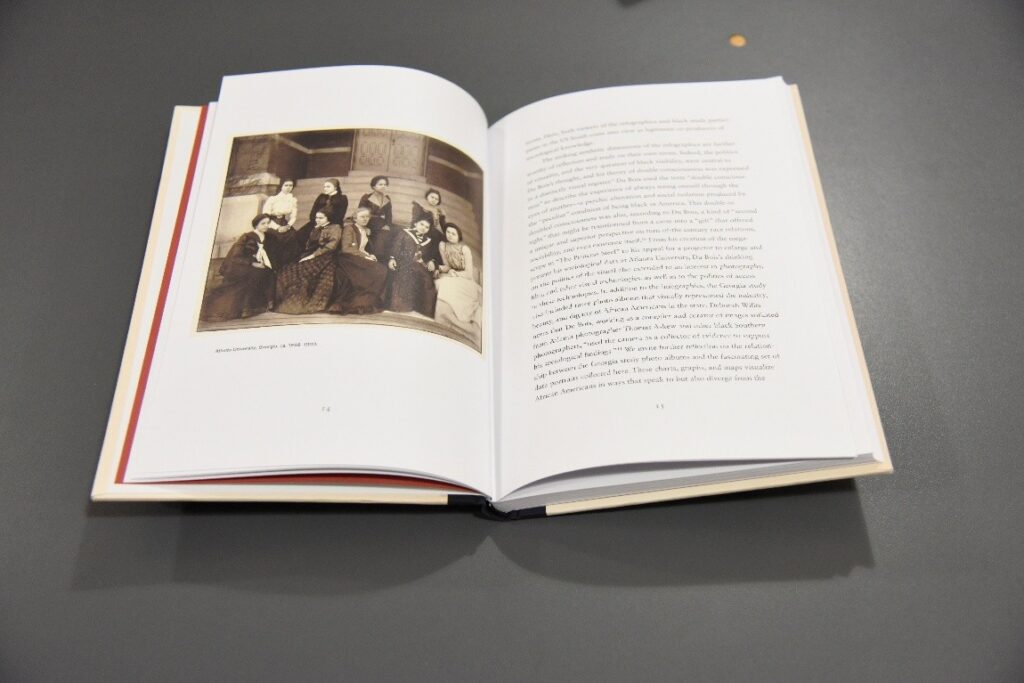

Photographs taken by Thomas Askew were placed in proximity to the ‘data portraits’ in the Paris Exhibition. One of these shown in Figure 5, within a book in our Library about the history of the production, display and provenance of these posters – hidden for decades. The visual played a strong role in communicating with the audience –through depicting different groups and professions of African Americans in context; through creating identifications in the face-to-face encounter of portraits; and through scientific visualisation of data (Smith, 2004). Klein et al (2024) argue this was deliberate curation by Du Bois, to humanise the lives of those visualised in the graphs, and often rendered insensible by social scientific methods. In an attempt to honour this relation, in the Library display I have placed selected a large print of ‘Nine African American women, full-length portrait, seated on steps of a building at Atlanta University, Georgia’ (Figure 5) in proximity to the poster ‘A series of statistical charts illustrating the condition of the descendants of former African slaves now in residence in the United States of America’ (Figure 4). Most of the posters I have chosen relate to formal education, and universities.

Figure 5 The data portraits were physically made by Du Bois’s students at Atlanta University, based on two social science studies he had led, which Battle-Baptiste and Russert (2018, 13) describe as projects in public sociology, informed by the fieldwork of Atlanta alumni who formed a ‘robust network of field researchers across the South’, including Black women. The academic women in this image are seated on the steps of Atlanta University. In his texts and in his work, Du Bois did engage with the question of women though his gender politics has seen much probing and critique (see for instance, a wealth of such work accessible through our Library).

Commemorating as consciousness about academic injustice

Portraits featured significantly in the Paris display. Similarly portraits adorn the cover, below, of Stephanie Evans’ book Black women in the ivory tower, 1850-1954 : an intellectual history (Figure 5). This text provides insights into the lives of Black academic women around the same period as Du Bois, between the Civil War and the civil rights movement. Importantly, it includes insights into their struggles for access at two borders to the university– access to higher education as a student, and access to employment as educators and researchers. These are the traditional routes to intellectual authority – through the university – which were barred due to imposed inequalities. The book recounts the politics of participation for Black women once such access was secured, revealing the ways in which they navigated the violence, discrimination and campus policies which served to maintain oppressive conditions against their academic flourishing.

Figure 6 This detail shows two of the three portraits of Black women in graduation gowns. Three such graduation portraits feature on Evans’ (2007) intellectual history of the ‘firsts’ to access higher education and ‘double firsts’ to access employment within predominantly ‘white’ universities in the USA (Photo: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast)

Commemoration as reclamation of a counter-canon

Reaching further back into time to de- and re-construct the intellectual histories which shaped North America, is the edited volume by Waters and Conaway (2007) (Figure 7). This is a reclamation of intellectual thought from before the time such thought would have been organised, or even recognised, by institutions in the Western world. Thus, within it one encounters the lives and thinking of activists, artists, literary figures, educators, journalists who contributed to Black feminist visions of resistance.

Figure 7 In the foreground of this photograph of a book about Black women’s intellectual traditions, is the subheading ‘Speaking their minds’. The book is an act of resistance to dominant canons of intellectual historiography. A detail of a page appears in Figure 1 above. (Photo: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast).

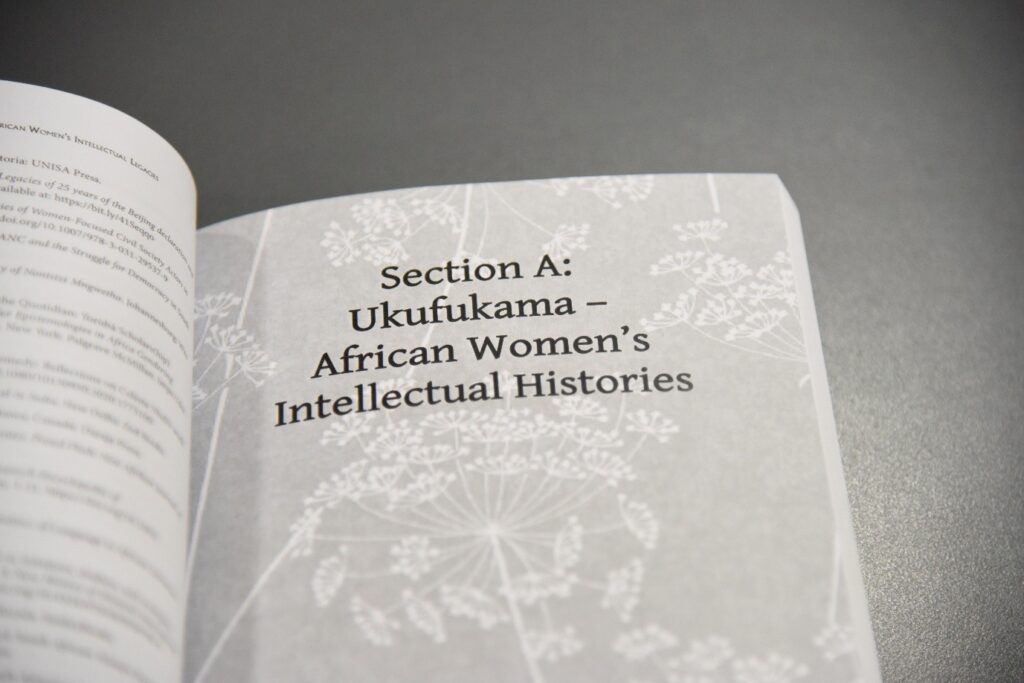

In the curated display, connections have been made to a similar act of reclamation in South Africa, a country which due to colonialism and then Apartheid, has only recently seen a critical mass of ‘firsts’ enter higher education and the professoriate. The very recently published text included in the display, is by the newly established Mandela University Press, Inyathi ibuzwa kwabaphambili: theorising South African women’s intellectual legacies (2024), edited by Babalwa Magoqwana, Siphokazi Magadla, and Athambile Masola. Within it, they too address misrecognition by shaping the book into different sections (Figure 8), with varied genres therein that pay homage to the voice of those alive and the recollections of those now past.

Foregrounding the isiXhosa language in the title is also a political act of staking the validity of that language within a time of the dominance of English in the global academic world. It translates to learning from the wisdom of those with experience of the road or journey you intend to take – a sense of intergenerational learning. The cover of the book has an artwork by a Black South African artist-academic, Nomusa Makhubu, wherein she is pictured with projections cast over her body, of pictures of those from the past. A matter of social justice are addressing the large gaps within South African archives generally, and in its visual history particularly (Thomas, 2021). Thus, in the display I have arranged the book to show its haunting cover.

Figure 8 Starting with this section of what might conventionally be understood as intellectual histories, the book by Magoqwana, Magadla and Masola (2024) expands to include political activists, social workers, artists and those with the gravitas of ‘elders’. (Photo: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast)

Commemoration for justice

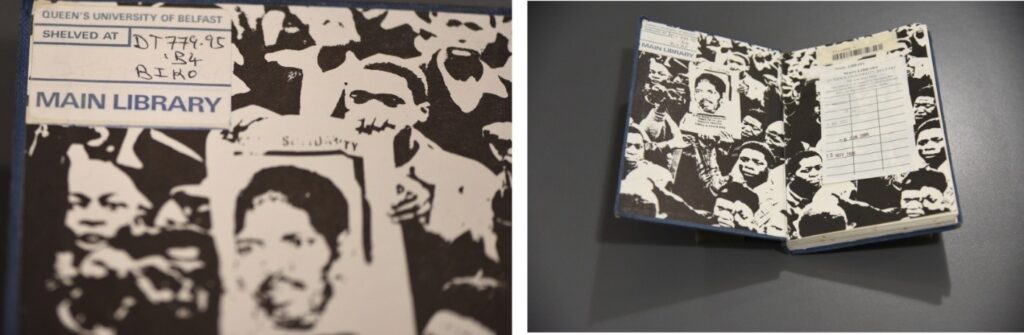

The only item in the display that comes from QUB Special Collections is a small, annotated pamphlet (Figure 11). In 2024, I focused on writing about it in the African Scholars Research Network’s collaboration to the Library’s blog for Black History Month (see Sotonye-Frank and Belluigi, 2024). The pamphlet was published posthumously, within the year of the death of the author, Bantu Steve Biko, a political dissident of the Apartheid regime. Accusations about those responsible for this murder are plainly recorded on its cover. Its publication is itself an act of resistance to denial about such culpability; and to counter the erasure of his thought and life by the Apartheid regime, which had banned him and banned the reproduction, citation or teaching of his writing and speeches within South Africa.

I was compelled to include this text again this year, because of the timing of a return to reckoning with the past, that has again awakened in my country. Those responsible for Biko’s death are yet to be held accountable. Just this year, the inquest into his death has finally been re-opened – as an act of commemoration, it was reopened on the 48th anniversary of his death, the 12th of September. This is in a wider context of the denial of justice for families of political dissidents who died or were disappeared; and the State avoidance of prosecuting those whom the Truth and Reconciliation Committee denied amnesty. The Foundation for Human Rights has established a website as an archive on these continued struggles for justice, including the 2025 case of those “seeking constitutional damages for the political suppression of the apartheid-era cases referred to the National Prosecuting Authority following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)” (https://unfinishedtrc.co.za/constitutional-damages-case/).

Figure 9 The inside cover of this edition is a photograph with protesters holding the banned portrait (left) of Bantu Steve Biko and the words ‘solidarity’ during the State of Emergency period, where his texts too were banned within the country. (Photos: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast)

The text within the Special Collections pamphlet can also be found within a book in the Main Library’s holdings, which too was published at a time when the text was still illegal within South Africa (Biko and Stubbs, 1978). In this book, one finds another act of resistance – this time in the inner cover. As outlined in the caption to Figure 9, the photojournalism visible in the double spread would have been censored in the country. The Apartheid state was particularly astute in its propaganda, and fearful of the power of knowledge and the visual on the social imagination. They attempted to constrain the production and dissemination of images, words and thoughts through legally prohibiting their utterance and circulation, including within universities. The editor of this publication was the priest Aelred Stubbs, himself barred from returning to the country at the time of its publication, who was a friend of Biko and supporter of many others, including the late Desmond Tutu. The relationship of faith, organised religion and resistance to political oppression is a strong undercurrent across many of the lives of academic citizens in countries where the university has not provided strong frames for ethicality and alterity.

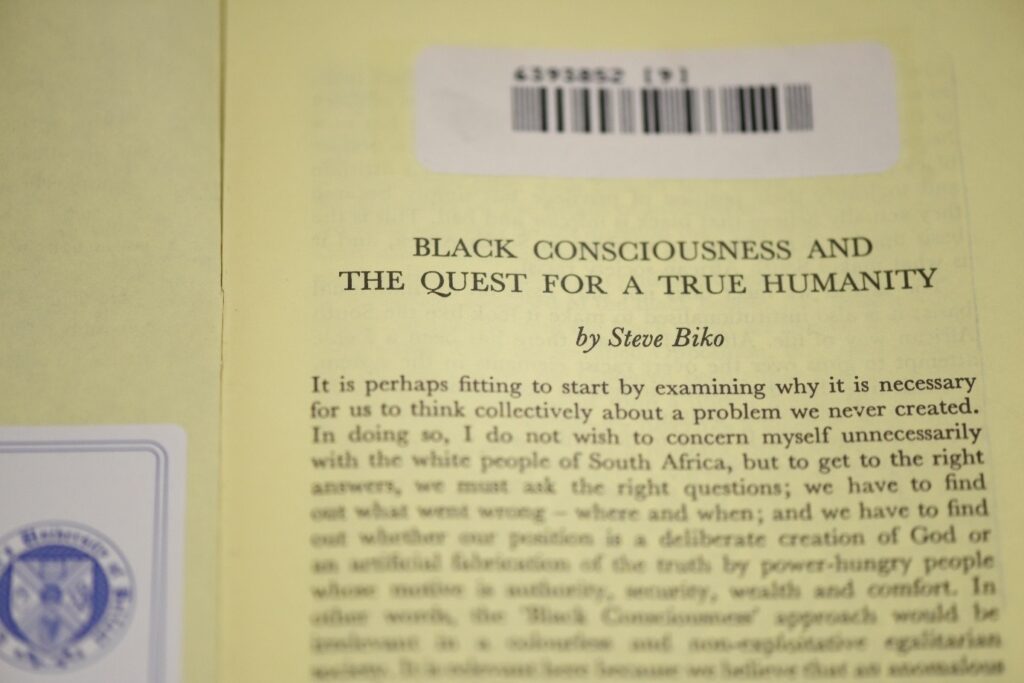

Biko’s work and thoughts about Black Consciousness continue to speak to current generations of youth in the country. Read his work to get a sense of its depth and complexity, including the demands required for challenging dehumanising psychosocial ideologies and systems of inferiority, which he developed from Franz Fanon and others. During the #Fallist movements which emerged from South African universities a decade ago, his name and words were amongst those cited to catalyse historical consciousness about resistance.

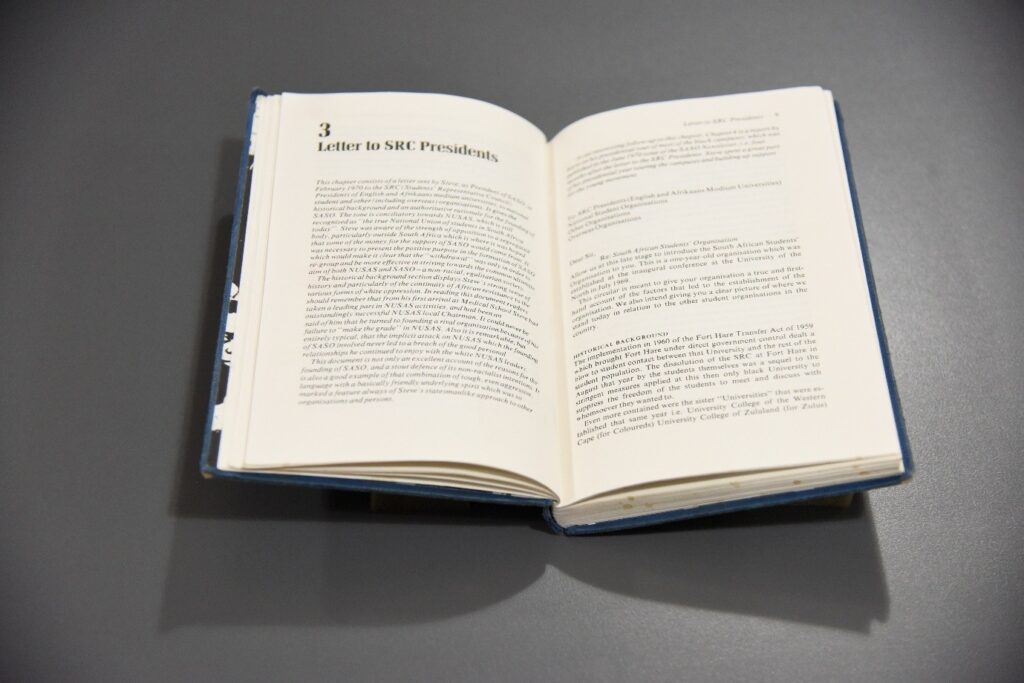

Figure 10 The third chapter is titled ‘Letter to SRC Presidents’. As a student himself, Biko mobilised support through student unions across the country. The agency of students, to exercise academic freedom to dissent, extended from school through to university during Apartheid, facing grave danger because the conditions for that freedom were not institutionally nor nationally protected. (Photo: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast)

As I mentioned in the introduction, Biko and Du Bois were conscious in their engagement with academic audiences. Biko was active in the student unions in the country, and played a foundational role in the formation of the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO), which was led by Black students and centred their experiences and demands. Figure 10 is a chapter which was written directly to student leadership in South African universities.

Against the divide-to-conquer raciological stratifications which typified grand and petty Apartheid, ‘Black’ was the term the Black Consciousness movement used to build solidarities across the State-projected categories ‘African’, ‘coloured’, ‘Indian’, ‘Asian’. Below is an extract from his writing signalling the importance of such solidarity:

For liberals, the thesis is apartheid, the antithesis is non-racialism, but the synthesis is very feebly defined. They want to tell the blacks that they see integration as the ideal solution. Black Consciousness defines the situation differently. The thesis is in fact a strong white racism and therefore, the antithesis to this must, ipso facto, be a strong solidarity amongst the blacks on whom this white racism seeks to prey. Out of these two situations we can therefore hope to reach some kind of balance – a true humanity where power politics will have no place.

Figure 11 Biko begins this text about Black consciousness quest for humanity, with a statement making clear his audience are socially marginalised, critical scholars: “It is perhaps fitting to start by examining why it is necessary for us to think collectively about a problem we never created”. (Photo: Dina Zoe Belluigi, 2025, Belfast)

For commemoration to ‘work’, it must remain imperfect

This extended essay has engaged with notions of representation, in visual and textual form, of resistance. I have touched on commemoration as remembrance, consciousness and reclamation against erasure and for justice, about two contexts connected against white supremacist oppression, and with love and humanity for Black peoples.

Both this form (a ‘blog’) and the McClay Library display, are humble contributions about such traditions, at a point in time when fortitude and transnational solidarities are again much needed to sustain broader anti-Black racism, anti-apartheid, anti-colonial, anti-war movements. These contributions are curated with the critical hope that historical consciousness – enriched by insights into past negotiations and theorisations of resistance from those operating within adverse institutional and national conditions – may serve towards that purpose. While there is indeed much to critique about the lives and legacies of such ‘greats’, studying them holds more meaning, to my mind, than those operating within normative or idealised frames. Putting principles into policies and into practice are important – and rightly, they should be fought for. However, they are weak against the forces of power we see again at play in so many contexts with belligerent leadership.

Much like the creation of monuments which materialise a principle or person of the past, acts of commemoration should not remove responsibility – for thought or for action – from the living. You are encouraged to engage with these texts for yourself. I was struck how the books displayed in this collection have little sign of wear and tear. This may be because they are being read digitally – or it may be a sign that teaching or studying Black resistance or intellectual resistance is not within mainstream formal curricula in our institution. Indeed, there is no African Studies on this island; Black Studies and Gender Studies continue to be marginal(ised). To produce this display and essay, I held and paged through texts that were once banned in my country, and were erased from my own education. To engage with them, continues to be very moving for me; just as it is to exercise the privilege of ordering books for our Library’s shelves, about new or reclaimed knowledges about women intellectuals.

Commemoration of the past should also not divert from the challenges of the present. Between the lines in this essay, are reverberations with current realities. To stay informed of these, a good place to start is The Free to Think Report which was published on the first day of this month.

Acknowledgements:

With thanks to QUB Special Collections team, particularly Natasha Kennedy and before that Andrew Harrison, for facilitating the display process; and to Norma Menabney’s assistance with ordering some of the books. With thanks to SSESW Athena Swann Committee, in particular Teresa Degenhardt and Mel Engman, for support in securing funds for printing the posters for this display. And to the members of the African Scholars Research Network for support of this idea.

All images included herein are licenced under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Please attribute the named photographer.

A note: Some of the ideas and foci within this blog later appeared within an article in the journal Criminological Encounters. As such, following its publication, this note was updated to reflect and acknowledge the formative connection to Belluigi, D. Z. (2025) Criminalisation of Intellectual Thought: Representations for Consciousness about Dissent, Refusal and Resistance. In Wilkinson, H. and Degenhardt, T. [Eds]. Special Issue: ‘We must persist! Towards a global criminology of war’, for Criminological Encounters, 7(1), 30-56. https://doi. org/10.26395/CE.2025.1.04 or https://www.criminologicalencounters.org/index.php/crimenc/article/view/180.

A note on the contributor:

Prof Dina Zoe Belluigi is based within the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work (SSESW) at Queens University Belfast, where she is the institutional representative on the Scholars at Risk Ireland Committee. She is a Fellow of the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice, and a member of the African Scholars Research Network (AfSRN). She is a Visiting Professor at CriSHET, Nelson Mandela University; and at the School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur University. She is an Africanist who was born, raised and educated in South Africa, a prior British colony with white supremacist ideologies that continued and morphed into Apartheid. Thus, her intellectual influences on the subject of intellectual resistance are informed by those who have problematised Western, liberal notions of academic freedom. She continues to look to that intellectual work which comes to the problem of academic freedom through commitments to collective freedom.

References:

Reproductions of Du Bois’ data portraits are in the public domain from the Library of Congress and Public Domain Review.

Al-Hardan, A. (2022). Sociology Revised: W. E. B. Du Bois, Colonialism, and Anticolonial Social Theory. In A. Morris, W. Allen, C. Johnson-Odim, D. S. Green, M. A. Hunter, K. L. Brown, & M. Schwartz (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of W.E.B. Du Bois (pp. 1–27). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190062767.013.50

Biko, B. S. (1978). Black consciousness and the quest for a true humanity. Christian Institute Trustees. Available at QUB Special Collections: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991005062209708046

Biko, B. S. and Stubbs, A. (1978). Steve Biko – I Write What I like: A Selection of His Writings, edited, with a personal memoir, by Aelred Stubbs. Bowerdean Press. Available at QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991003409659708046

Battle-Baptiste, W. & Rusert, B. [Eds} (2018). W.E.B Du Bois’s data portraits: visualizing Black America. Princeton Architectural Press. Available at QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991008772543408046

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2007) The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century; Introduction by Arnold Rampersad. Oxford University Press. Available at QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991005206279708046

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2007). The Gift of Black Folk: The Negroes in the Making of America; Introduction by Glenda Carpio. Oxford University Press. Available at QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991005205939708046

Du Bois, W. E. B. (2007). Africa, Its Geography, People and Products and, Africa, Its Place in Modern History; Introduction by Emmanuel Akyeampong. Oxford University Press, Available at QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991005206149708046

Evans, S. Y. (2007). Black women in the ivory tower, 1850-1954: an intellectual history. University Press of Florida. Available in hardcopy and digital from QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991003176659708046

Guy, T. C., & Brookfield, S. (2009). W. E. B. Du Bois’s Basic American Negro Creed and the Associates in Negro Folk Education: A Case of Repressive Tolerance in the Censorship of Radical Black Discourse on Adult Education. Adult Education Quarterly, 60(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713609336108

Klein, L., Sharma, T., Varner, J., Li, S., Adams, M., Yang, N., Jutan, D., Fu, J., Mola, A., Fang, Z., Li, Y., and Munro. S. (2024) Data by Design: An Interactive History of Data Visualization, 1789-1900. 2024 public beta. https://dataxdesign.io/chapters/dubois

Magoqwana, B., Magadla, S., & Masola, A. (Eds.). (2024). Inyathi ibuzwa kwabaphambili: theorising South African women’s intellectual legacies. Mandela University Press. Available at QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991008732744008046

Morris, A. D. (2015). The Scholar Denied: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology. University of California Press. Available only through QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991008587351708046

Scholars at Risk. (2025). The Free to Think Report. Available at: https://www.scholarsatrisk.org/free-to-think-reports/

Sinitiere, P. L. (2016, February 18). W. E. B. Du Bois and Black History Month [AAIHS]. Black Perspectives. https://www.aaihs.org/w-e-b-du-bois-and-black-history-month/

Smith, S. M. (2004). Photography on the Color Line: W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11hpr39

Thomas, K. (2021). Digital Visual Activism: Photography and the Re-Opening of the Unresolved Truth and Reconciliation Commission Cases in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Photography and Culture, 14(3), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/17514517.2021.1927370

Waters, K., & Conaway, C. B. (2007). Black women’s intellectual traditions: speaking their minds. University Press of New England. Available in hardcopy or digital at QUB Library: https://qub.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44QSUB_INST/1srh3fv/alma991003900089708046