Are You Sitting Comfortably? Then I’ll begin…

This seasonal blog was written by Ivona Coghlan, Borrower Services, QUB

The long dark nights are the best time to immerse yourself in a good old yarn. Whether that’s sticking on a Disney movie, cracking open a book or simply telling your nearest and dearest a story, there is something very satisfying about having a little fantasy to warm up a cold winter.

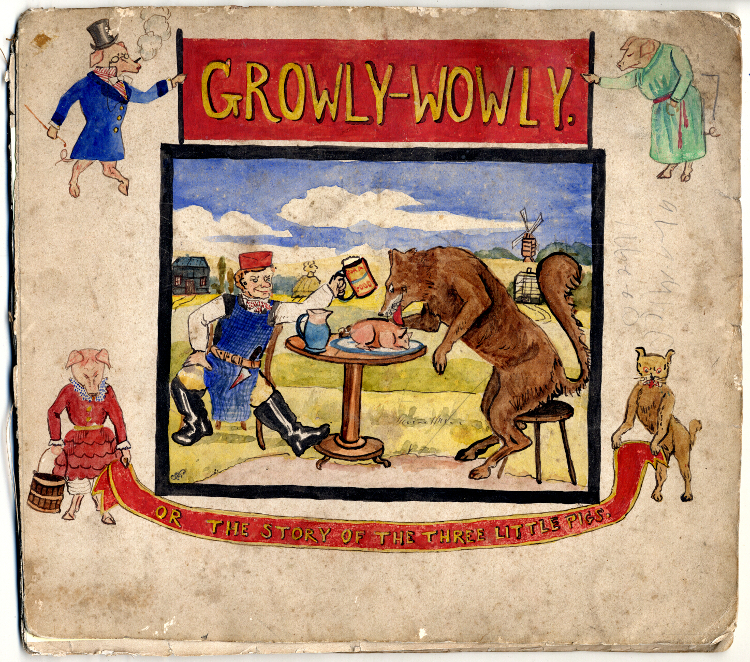

Growly-Wowly, or The Three Little Pigs by Edith Somerville.

The original manuscript of an unpublished book for children.

Humans have been telling each other stories for years and these stories have grown into the fairy tales and folklore we know today. We all know that some tales have been around for yonks but it might surprise you to know that many are now thought to predate Ancient Roman and Greek texts. Beauty and the Beast and Rumpelstiltskin are now thought to be 4000 years old. The oldest identified folk tale is The Smith and The Devil, which is thought to be around 6,000 years old. These stories were probably told in a long extinct Proto-Indo-European language[1]. Being librarians we like to think that the written word is paramount but even we must admit these stories have initially been preserved in the telling.

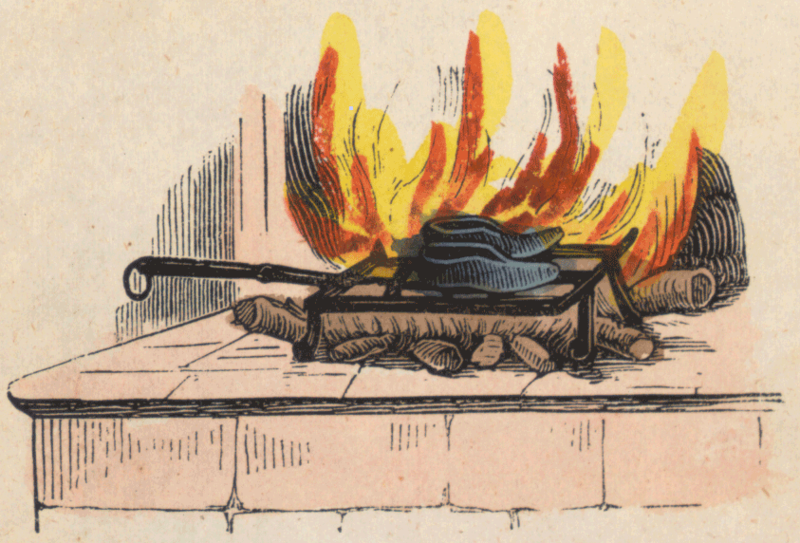

It is common knowledge that fairy tales have many versions. Most people will know that Disney sanitised a lot of its fairy tales to make them more commercially friendly. For example, does anyone remember that bit at the end of Snow White where the evil queen goes to Snow White’s wedding and is forced into iron shoes that have been heated in burning coals? Then, there’s that cheerful part where they make her dance until she dies. Also, in the original Grimm version, she’s actually Snow White’s biological mother[2]. And you thought your family drama was bad!

Looking at the growth of fairy tales in various texts allows us to see changing attitudes and the impact of various cultural differences. (See, we had to get some library stuff in somewhere!) It has been pointed out that the same story has been told all over the world. There are two possible reasons for this. One, is that they all come from some shared source, like The Smith and the Devil. The other is that they tell us something about human experience. We relate to these stories because, there is something universal we all share that we are all trying to describe through these stories[3].

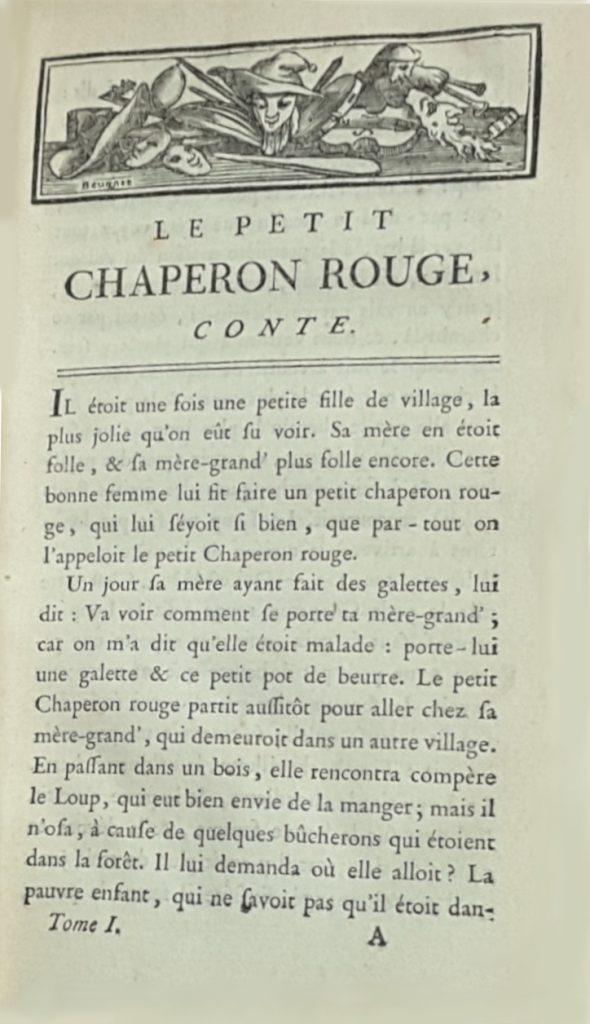

The European fairy tales were eventually written down. Straparola is believed to have produced the first printed work of fairy tales back in 1551[4]. His story, Constantino Fortunato is the first printed telling of Puss in Boots, everyone’s second favourite Shrek character. These tales inspired the works of Madame d’Aulnoy, the Brothers Grimm and Perrault. The Nights of Straparola and Le cabinet des fées, both available to consult in the library at Queen’s, are volumes which contain fairy tales from over 40 authors collected by Joseph de Mayer in order to save them from oblivion[5]. It is hard to attribute these tales to any one person. The authors mentioned may just have been the first to record them. Straparola, himself, was said to have taken many of his tales from Gerolamo Morlino, something which he never denied.

Hans Christian Andersen is a slightly different kettle of fish. While he claims some of his tales were based on stories he heard as a child, they are certainly more obviously crafted by him. It is fair to say his stories not only contain elements of his Danish homeland but have influenced Denmark itself. Many people flock to see The Little Mermaid statue in Copenhagen (It’s unfortunately described as one of the most disappointing landmarks in the world, but hey what can you do?[6]).

Still Hans Christian Andersen’s stories inspire people around the globe in different ways. Frozen is loosely based on his story, The Snow Queen. You can see this in its Scandinavian-like kingdom and Queen with powers over ice and snow. It’s hard to see that Elsa is any relation to the Snow Queen until you find out that she was originally meant to be the villain with blue skin and a scorned heart[7]. If you are interested you can see some of the original concept art here and here. Andersen has also inspired people a little closer to home. Harry Clarke’s first illustrations in print were to accompany a collection of Andersen stories. These can now be viewed in the National Gallery of Ireland.

Dublin : Gill & Macmillan, c2011.

While you may agree Andersen’s stories reflect his culture, you may be struggling to think of an Irish equivalent, possibly because Irish folklore is so embedded in our culture that rarely is it referred to as fairy tales. Yet, it features a lot of the typical magical tropes, albeit with an Irish slant. Mentions of banshees, Tír Na nÓg (the land of youth), leprechauns and pucas are common. Ireland is one of those countries where fairy tale, folklore and fact all lie very closely together. Yeats argued that:

‘The ghosts and goblins do still live and rule in the imaginations of the innumerable Irish men and women, and not merely in remote places, but close even to big cities.’

I can hear you say, “Well yes back when Yeats was writing maybe but now we are all sophisticated pragmatic people.” And yet to this day there are numerous examples of people refusing to cut down a fairy bush[8]. They believe it will bring them bad luck. In 1999, a motorway in Clare was designed to incorporate the fairy bush or “seach[9]” and planners were warned that destroying it could cause misfortune and death on the new road. Maybe you think this is ridiculous. Maybe you can’t believe people still act like that. But would you do it? Would you be the one to cut down a fairy tree?

A lesser known fact about Irish tales is that they provide excellent evidence of diffusion. In 1892, Joseph Jacobs, an Australian folklorist, published his first of two collections of Celtic Fairy tales. He highlighted stories such as the tale where Conall Yellowclaw blinded a one eyed giant. The hero stealthily sneaks past the giant, clothed in a buckskin. This echoes the story of Polyphemus from the Odyssey[10]. Another hallmark of Irish fairy tales is they contain a mix of both pagan and Christian elements[11]. This shows the extent folk tales were built into the zeitgeist. Instead of these stories being obliterated by Christian stories or discarded, it made more sense to the Irish sensibility to meld them together.

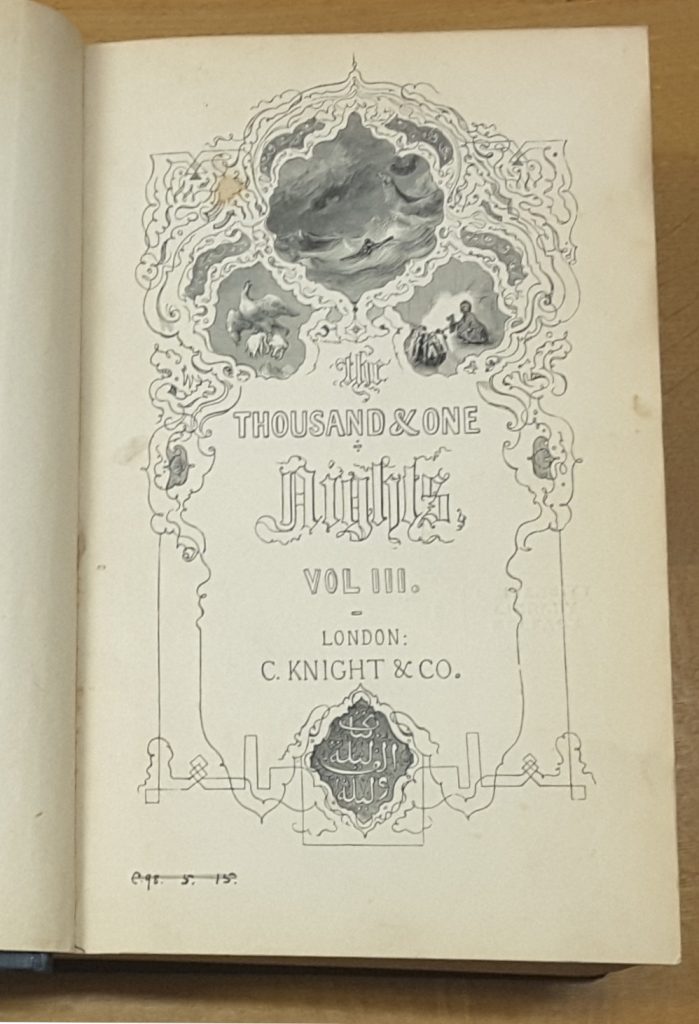

Let us now be whisked away to the world of Arabian Nights. Also known as 1001 nights, these tales have been entertaining people for centuries. Many children know some of these stories as well as they know Cinderella or Little Red Riding Hood. Arguably, the best known are Ali Baba, Aladdin and Sinbad. Maybe some of you know the framing story. Schereazade is married to a Sultan who weds a new bride every night and has them executed each morning. In an effort to survive. Scheherazade tells stories to the Sultan, always ending on a cliff-hanger so he will spare her life for another night. Although often packaged together, The Arabian Nights come from a wide variety of sources. The original Thousand Nights was probably published in the 8th century and was a reasonably small collection. Then in Iraq, in the 9th or 10th centuries, more stories were added. The collection continued to grow to include stories from Syria and Egypt. These were then padded out further by various people[12]. For example, the first European translation by Galland includes stories that are only found in his version and are in none of the original manuscripts. Galland claimed he heard them from a Maronite Scholar from Aleppo. It may shock you to know these additions included both Ali Baba and Aladdin, two of the stories European audiences know best. It is also interesting to note that Aladdin originally took place in China, not the mysterious kingdom of Agrabah!

Because there are so many different manuscripts, translations and re-imaginings of The Arabian Nights, it is incredibly hard to pin down the original, ‘authentic’ collection. However, the various versions of the text continue to inspire and inform new creations.

As I hope we’ve shown, the study of fairy tales teaches much about culture and change. Between the Grimm Brothers eventually deciding that it would be much more acceptable if Snow White’s step-mother tried to kill her or Disney deciding that the Ugly Step Sisters getting their eyes pecked out was a bit much, the alterations are fascinating to trace. Still, the most interesting thing about these stories is simply that they have lasted, been preserved and reinvented continuously even as human civilisation has evolved beyond all recognition. It suggests that somewhere, at the heart of it, stories are an intrinsic part of being human.

[1] BBC News, Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-35358487 (accessed 17 October 2019)

[2] Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, Little Snow White, https://www.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm053.html (accessed 17 October 2019)

[3] Paul and Andreas Moxnes, Are We Sucked into Fairy Tale Roles? Role Archetypes in Imagination and Organization, in Organization Studies Vol 37, Issue 10, 2016, p.1519 -1539, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0170840616634135 (accessed 17 October 2019)

[4] Suzanne Manganini, Straparola. Europe’s First Literary Fairy Tales, https://ucbfairytales.wordpress.com/italian-fairytales/straparola/(accessed 17 October 2019)

[5] https://biblioweb.hypotheses.org/2669 (accessed 17 October 2019)

[6] https://www.europeish.com/overrated-disappointing-landmarks/ (accessed 17 October 2019)

[7] https://www.businessinsider.com/frozen-elsa-originally-villain-2014-9?r=US&IR=T (accessed 17 October 2019)

[8] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-31459851) (accessed 17 October 2019).

[9] https://www.irishtimes.com/news/fairy-bush-survives-the-motorway-planners-1.190053 (accessed 17 October 2019).

[10] Richard Mercer Dawson, History of British Folklore, Volume 1, 1999, p.488

[11] https://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/source/the-irish-fairy-book-by-alfred-perceval-graves/ (accessed 17 October 2019).

[12] https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Thousand-and-One-Nights (accessed 17 October 2019)