Reblogged from the Centre for Public History, Queen’s University Belfast.

Photographs Between Two Worlds: the Hart Photographic Collection

Emma Reisz

In 1854, a nineteen-year-old from Portadown set sail for Hong Kong. His name was Robert Hart, and he was a recent graduate of the newly established Queen’s College Belfast. He had been nominated by Queen’s to join Britain’s Chinese Consular Service as a trainee interpreter, though he had no connections in China, and spoke no Chinese.

The son of a distillery manager, Hart had no experience of politics or foreign affairs either. On his way east, he stopped off in London, where the genteel diplomat Edmund Hammond gave the teenage Hart some words of advice for life in China: ‘Never venture into the sun without an umbrella, and never go snipe shooting without top boots pulled up well to the thighs.’1

On his arrival in Hong Kong, Hart reached a typically phlegmatic assessment of his circumstances. ‘This climate – the diseases it produces – may lay me in the dust,’ he told his diary. But, he consoled himself, ‘shall I not rest as well beneath the rocky soil of this "Happy Valley" as though I lay in Drumcree Churchyard, mine mingling with the dust of my forefathers?’2

Robert Hart c. 1867. MS 15/6/1/B2.

All images courtesy of Special Collections, Queen’s University Belfast. All rights reserved.

Despite this inauspicious start to his career, in 1863 Hart became Inspector-General of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs aged only twenty-eight, a post he went on to hold for forty-five years until 1908. In a generally indulgent biography, Hart’s niece Juliet Bredon noted her uncle was once described as ‘a small, insignificant Irishman’.3 Few of his contemporaries would have recognised that assessment, however.

By 1900, the customs service over which Hart presided had a staff of almost twenty thousand and raised the bulk of Qing imperial revenue, and his influence extended far beyond the Customs. Hart transformed China’s infrastructure, establishing a postal service and a network of lighthouses, and helped to shape the foreign relations of late imperial China. Hart exerted such wide-ranging influence that the historian John Fairbank called him one-third of the ‘trinity in power’ in China in the later nineteenth century.4

The Hart Photographic Collection at Queen’s

The Sir Robert Hart Project at Queen’s University Belfast, led by Emma Reisz and Aglaia De Angeli in History and by Deirdre Wildy of Special Collections, is exploring the life and career of this remarkable and controversial figure, making use of Hart’s large archive of personal papers which was bequeathed to Queen’s by his great-grandson in 1971. The collection includes Hart’s seventy-seven volumes of diaries (the subject of an upcoming blog post by Kath Stevenson) and a large collection of photographs, as well as letters, memorabilia and materials from Hart’s writings. An important focus of the project is to share material on Hart with a wide audience, by digitising and exhibiting materials from the collection.

The Hart Project is now undertaking a substantial public history project to catalogue, digitise and research the Hart Photographic Collection. While historians have long recognised the importance of Hart’s diaries, letters and other written materials, his photographs have received far less attention. Hart’s personal collection amounts to over 2,500 photographs, mostly taken in China between 1860 and 1910, and many of them unique.

Though not a photographer himself (so far as we have yet discovered), Hart was a keen collector of photography, particularly by his friends and acquaintances. He also commissioned photographers to record important events.

Apparently loaded into two trunks at the time of Hart’s departure from China, the photographic collection now amounts to twenty-three original albums and three boxes of glass slides, as well as numerous loose photographs held in boxes and other containers. Alongside many photographs of Beijing, the collection traverses China from the southwest to the northeast. Some are of outstanding artistic value and some are inexpert snapshots. The topics range from quotidian street scenes to major historical events.

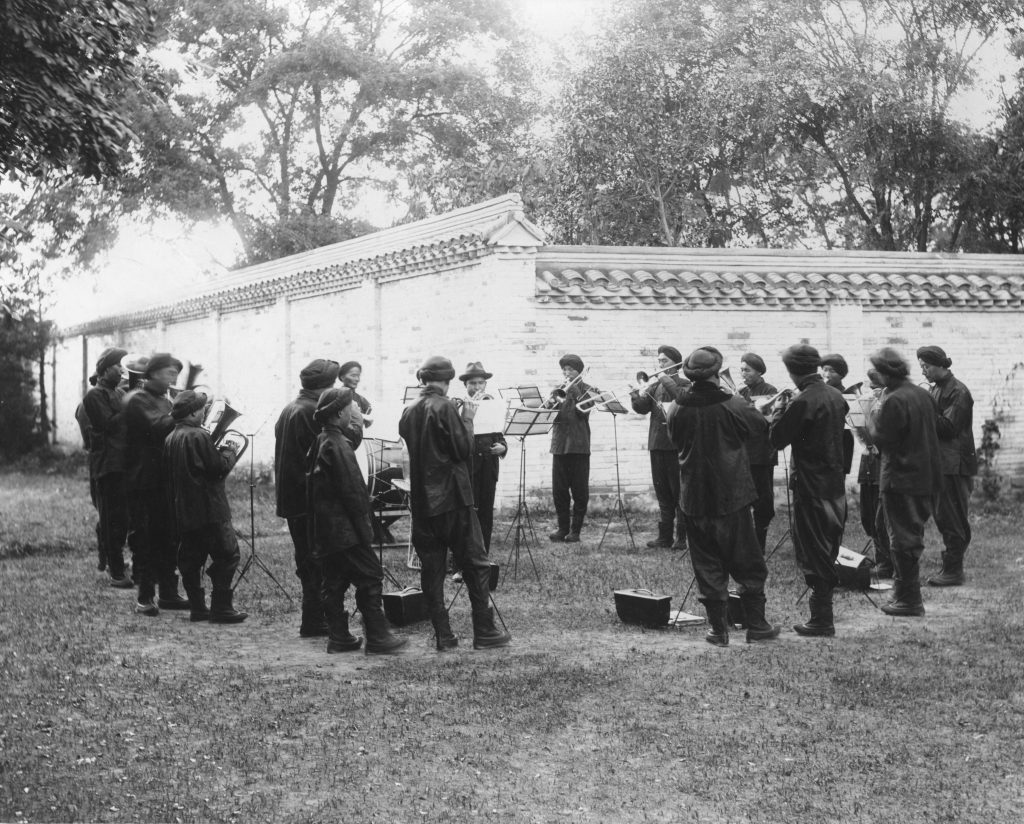

Hart’s personal brass band playing in the garden of his house in Beijing, c. 1903. MS 15/6/9/2a.

Hart’s personal brass band playing in the garden of his house in Beijing, c. 1903. MS 15/6/9/2a.

The photographs have been called the ‘most delightful’ of the historical sources relating to Hart, but they could also have been termed the most diverting of these sources.5 Photographs are always evocative, trapping history – or one individual’s momentary view of it – like a butterfly and ‘imprisoning reality’ to use Susan Sontag’s phrase.6 Sometimes the Hart photographs complement the textual materials, but sometimes they lead the historian into entirely new territory.

Photography can also help us to to understand how people in the past saw the world around them, showing us ‘a perspective that is sure to be different from [our] own’.7 By providing a visual sense of how Hart and his circle saw China, Hart’s photographs help to show how he perceived his work, his personal life, and the country he served.

The Boxer Uprising

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Hart’s photographic collection is its mere existence. Most of the thousands of images in the collection were acquired in just eight years, between 1900 and 1908. Hart’s first photography collection was largely destroyed on the night of 13 June 1900, when all the Customs buildings, including Hart’s house, were burned down in the siege of the Legation Quarter of Beijing during the Boxer Uprising.

Hart’s house was destroyed during the Beijing Legation Quarter siege. Summer 1900. MS 15/6/6/1.

Hart’s house was destroyed during the Beijing Legation Quarter siege. Summer 1900. MS 15/6/6/1.

Hart’s private archive, like the rest of his possessions, was lost in the flames almost in its entirety, though a Customs assistant, Leslie Sandercock, was able to take Hart’s diaries to safety. So complete was the destruction of his belongings that when Hart was finally able to contact the outside world, his first act was to telegraph for four suits from London, noting ‘I have lost everything but am well’.8

A number of Customs staff volunteered in the defence of the legations. Hart’s brother-in-law Robert Bredon is standing second from right. Summer 1900.

A number of Customs staff volunteered in the defence of the legations. Hart’s brother-in-law Robert Bredon is standing second from right. Summer 1900.

Hart’s distress at the loss of his photographs was considerable. Months later in May 1902, an 1899 photo belonging to Hart was found in the street and returned to him, but Hart misplaced it a few days later, to his ‘great grief’.9 The lost photograph included Robert Beatty de Courcy from Ballyclare in County Antrim, whom Hart had nominated to a post in China and who had been commended for his bravery during the siege. Beatty de Courcy died a few weeks after the siege was lifted, aged only twenty-four.

Hart suspected the photograph had been taken by someone with access to his office. Theft would have been a notably bold act towards a man known as an ‘absolute autocrat’ to his staff.10 Perhaps the thief – if there was one – was motivated by the same kind of emotional response as Hart himself had to the image of Legation life before the siege.

A noble pair of brothers

The complex borders of friendship between Hart and the Chinese are also apparent in the collection. Perhaps the most intimate image of a Chinese is a photograph of Hart with his butler of many decades, Chan Afang (also referred to as Ah Fong). Afang had been in Hart’s employment from at least 1863 and, combining Horace and Virgil, Hart captioned the 1906 photograph with ‘Par nobile fratrum Arcades ambo‘ [A noble pair of brothers, both Arcadians].11

With his butler Chan Afang, 9 October 1906. MS 15/6/8E/14i.

With his butler Chan Afang, 9 October 1906. MS 15/6/8E/14i.

The brotherly commonalities between the two men are on display in this image. Of similar age, height and weight (Hart was a notoriously frugal eater), both are dressed in pale colours, as they stand together in an informal pose. After more than fifty years in China, however, Hart (who considered himself simultaneously Irish, British and even English) still looks every inch the Briton abroad, his outfit completed with a pith helmet of the pattern preferred by Victorian imperial administrators. The advice Hart received from Lord Hammond as a teenager to cover his head in the sun had apparently hit home.

In ‘double harness’

The collection is valuable as much for what it omits as what it includes. For much of the period 1857 to 1866, Hart lived with a Chinese woman, Ayaou, with whom he had three children and whom he described as ‘a very good little girl and well behaved’.12 He ended that relationship so he could form a socially appropriate marriage, and his children with Ayaou were sent to school in England without their mother.

Hart’s children with Ayaou have only a ghostly presence in the archive at Queen’s, marked mostly by their absence and excision from the record. The exception is a pair of legal statements asserting their illegitimacy which Hart made with the intent of preventing them making claims on his estate.13

Hart’s capacity for detachment towards his Chinese family was echoed, in a different way, with his Irish wife. Shortly after breaking with Ayaou in 1866, Hart married a Portadown woman, Hester (Hessie) Bredon, with whom he had three more children.

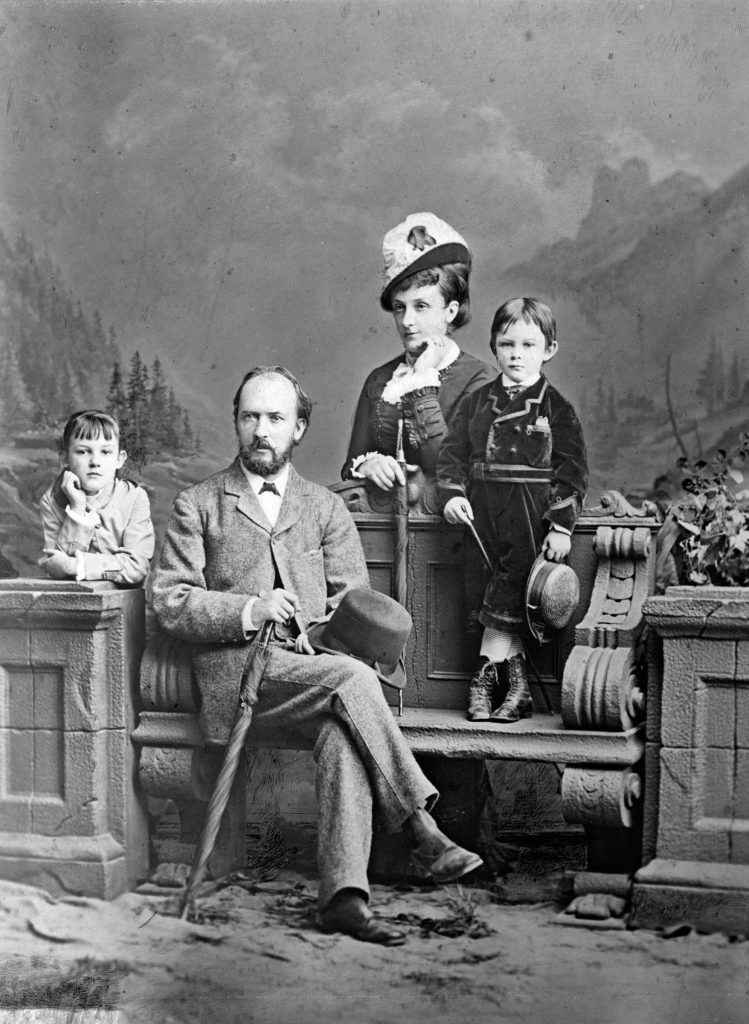

Hart with his Irish wife Hester (Hessie), née Bredon, and his two elder children with her, Evelyn and Edgar Bruce, c. 1878. MS 15/6/1/C1.

Hart with his Irish wife Hester (Hessie), née Bredon, and his two elder children with her, Evelyn and Edgar Bruce, c. 1878. MS 15/6/1/C1.

In this studio photograph taken during a holiday in Europe, Hart appears somewhat set apart from his family. Hessie’s pose behind the bench may have been because she was pregnant with Mabel, her third and last child. In 1882, Hessie left China and did not return for over twenty years. By the time she came for a final visit in 1906, Hart had lost interest in family life, writing that he hoped his wife and daughter would not remain too long in China as he prepared for retirement, since ‘after two dozen years of solitariness, I don’t run as easily in double harness…. I want to be alone to attend to the hundred and one things "winding up" will involve’.14

A life in two worlds

Hart had spent his career as a ‘man of two worlds’, in Martin Lynn’s phrase, optimistic that the Western presence could benefit both China and the West, and attempting to balance Chinese and Western interests.15

Hart leaving China for the last time. Shanghai, 1 May 1908. MS 15/6/6/44.

Hart leaving China for the last time. Shanghai, 1 May 1908. MS 15/6/6/44.

But by the time Hart left China for good in May 1908, he had reached the view that the West’s position in China was ultimately unsustainable. The Boxers, he thought, had ‘intended to destroy Christian converts and stamp out Christianity and to free China from a foreign cult, and on the whole not to hurt or kill but to terrify foreigners, frighten them out of the country and thus free China from the intrusion of aliens’. Hart believed that ‘this is the object which will be kept in view, worked up to and in all probability accomplished during the new century’. It was, Hart concluded, ‘time for new methods, new measures and new men’.16

More photographs from Hart’s life between two worlds can be seen in the China’s Imperial Eye exhibition at The McClay Library and the accompanying book, Aglaia De Angeli and Emma Reisz, China’s imperial eye: photographs of Qing China and Tibet from the Sir Robert Hart Collection, Queen’s University Belfast (Belfast, 2017).17

-

Juliet Bredon, Sir Robert Hart: the romance of a great career (London, 1909), pp 24-5.↩

-

Hart diaries, 28 Aug. 1854 (Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections [hereafter QUBSC], MS 15/1/1), p. 13.↩

-

Bredon, Sir Robert Hart, p. 250.↩

-

John King Fairbank, Trade and diplomacy on the China coast: the opening of Treaty Ports, 1842-1854 (Cambridge MA, 1964), p. 465.↩

-

The I. G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868-1907, ed. by John King Fairbank, Katherine Frost Bruner, and Elizabeth MacLeod Matheson, 2 vols (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975), vol. 1, p. xix↩

-

Susan Sontag, On photography (New York, 1977), p. 163.↩

-

Justin Court, ‘Picturing history, remembering soldiers: World War I photography between the public and the private’ in History and Memory, xxix, no. 1 (2017), pp 96-7.↩

-

Hart to Campbell, 5 Aug. 1900, in The I. G. in Peking, vol. 2, p.1238n2.↩

-

Hart to Campbell, 11 May 1902, in The I. G. in Peking, vol. 2, p.1313.↩

-

Vanity Fair, ‘Sir Robert Hart’, Men of the Day, no. 608 (1894).↩

-

QUBSC, MS 15/6/8E/14i.↩

-

Robert Hart, Declaration, Peitaiho, 19 August 1905 (QUBSC, MS 15/8/F/10).↩

-

Lan Li and Deirdre Wildy, ‘A new discovery and its significance: the statutory declarations made by Sir Robert Hart concerning his secret domestic life in 19th Century China’ in Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, lxiii (2003), pp 63–87.↩

-

Hart to Campbell, 6 May 1906, in The I. G. in Peking, vol. 2, p. 1503.↩

-

Martin Lynn, ‘Robert Hart: a man of two worlds’ in China Now, June 1988 (http://www.sacu.org/hart.html), p. 27.↩

-

Hart to Campbell, 29 Sep. 1907, in The I. G. in Peking, vol. 2, p.1533.↩

-

See also Emma Reisz and Aglaia De Angeli, ‘The Robert Hart photographic collection at Queen’s University Belfast’ in International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter, no. 78 (Autumn 2017), pp 7-8.↩