Beginning a series of guest posts by colleagues utilising Geographical Information Science at GAP, Professor Keith Lilley writes on the often overlooked but internationally important survey heritage of the Island of Ireland.

Ireland was the first country in the world to be fully surveyed and mapped at a scale of six-inches to one mile. As we approach the bicentenary of this ambitious and audacious achievement – begun in earnest in 1824 – it is time surely to take a close and critical look at what survives of Ireland’s surveying heritage?

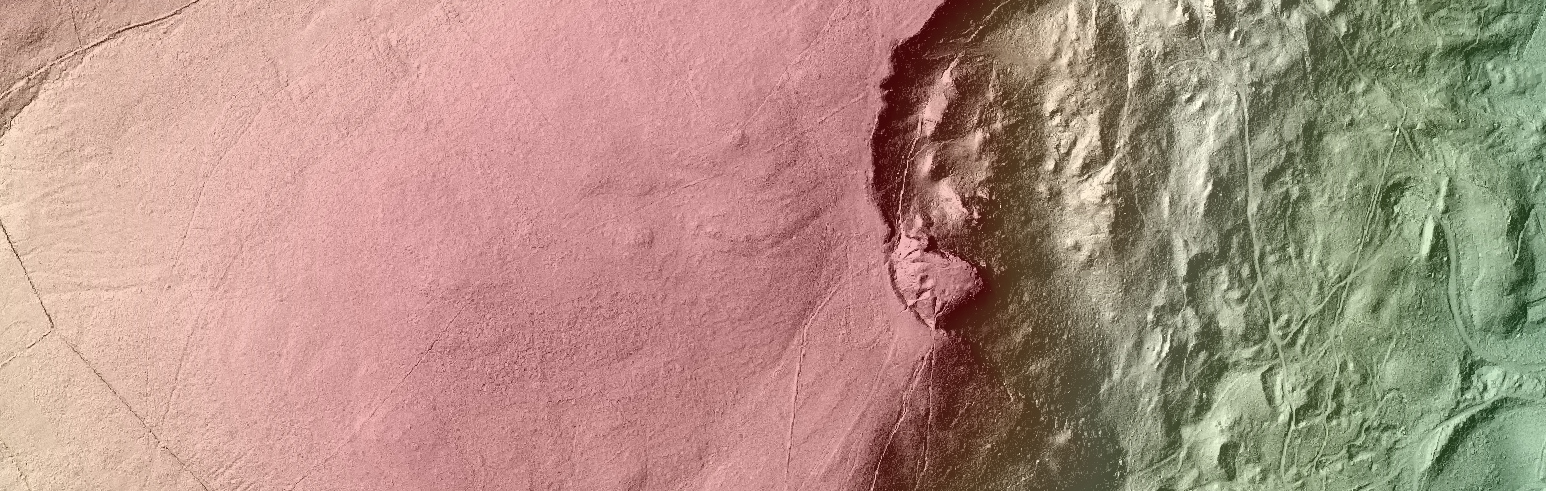

Behind the lines of the six-inch maps produced by the Ordnance Survey in Ireland in the 1830s lay an invisible yet crucial network of survey lines, connecting with ‘stations’ set out on the island’s highest points. These primary ‘trigonometrical stations’ are not those familiar grey concrete pillars dotted about the country that we recognise today as ‘trig points’ – these were put up in the middle part of the last century. Instead, the markers used for the original trigonometrical stations of Ireland have vanished, their sites recalled now only by the small triangles that the mappers marked on the Ordnance six-inch maps to indicate the locations of the ‘stations’.

No doubt if archaeologists were to dig at many of the locations of these lost trig points of the primary triangulation of Ireland they would reveal the buried stones that were laid into the earth to indicate to future surveyors their whereabouts. But Ireland’s surveying heritage is not just concealed on lonely mountain tops. Take a closer look and it is everywhere, marked on buildings all across the island, in the form of bench marks, chiselled into stonework that still stands in many cases, the familiar ‘crow’s foot’ of the levelling mark that acted as a reminder to those surveyors levelling the land in the 1840s and 1850s, of where their surveying staffs were placed.

Lost trig points, forgotten benchmarks, the heritage of Ireland’s surveyors has for too long been overlooked. Yet these marks on the land, and the work of those who made them, had a profound and lasting impact not only on Ireland but the rest of the world. The Ordnance surveyors of Ireland of the 1820s and 1830s, led by Colonel Colby, were part of a much wider global network, shaping the mapping of India and Africa, for example. Recognising and valuing the surveying heritage of Ireland has to be seen in this context, raising its importance from the national to the international stage of heritage under threat. Already UNESCO has conferred listed World Heritage status to the geodetic sites connected with the Struve Arc. So how about other examples of surveying heritage?

As if to underline the threat to Ireland’s surveying heritage, it is only necessary to look at what has happened to the Mount Sandy base tower, at Magilligan Point in County Derry. The tower once atop a dune, is no more, lost to the Atlantic Ocean. It was one of a line of stone towers constructed in the 1820s as part of the Lough Foyle Base Line, a very accurately measured line set out by the Ordnance surveyors, from which all the other calculations for the triangulation of Ireland derived. The Lough Foyle Base Line was the scientific basis of Ireland’s six-inch mapping, and it is of significant historical and cultural value, yet its northern terminal tower – at Mount Sandy – disappeared under the waves with hardly any notice let alone an assessment or evaluation.

It is time surely – before it is too late – to start documenting Ireland’s surveying heritage, to raise greater awareness of its significance, locally, nationally, and internationally. In doing so, the tools and techniques of twenty-first century Geographic Information Science (GI) and Geomatics provides a firm basis, as firm as Colby’s Lough Foyle Base Line did in the 1820s, at the start of the trigonometrical survey of Ireland. Indeed, there is something fitting in linking these cultural legacies of state-of-the-art spatial technologies of the past, used in the first large-scale survey of all Ireland, with those technologies at our disposal today.

Whether it is locating the sites of lost trig stations or base towers, or documenting surviving benchmarks on buildings and monuments, LiDAR (Aerial and Terrestrial) and GNSS based survey, coupled with GI Systems and historic and modern geospatial data, provides scope to record, evaluate and interpret Ireland’s surveying heritage, opening it up to greater recognition during the bicentenary, and recording what is there before it is gone. At Queen’s this work has already begun, using the GIS Research & Teaching Unit’s geospatial and heritage science expertise to make a start on identifying historic surveying sites at risk, and develop links with stakeholder groups and bodies with a shared interest with ours in protecting the cultural legacies of the work of the Ordnance Survey in Ireland.

![members of the Charles Close Society [link to http://www.charlesclosesociety.org/] at the site of first primary trigonometrical station in Ireland, Divis, photo K. Lilley]](https://blogs.qub.ac.uk/gis/wp-content/uploads/sites/67/2015/11/Members-of-the-Charles-Close-Society-at-the-site-of-first-primary-trigonometrical-station-in-Ireland-Divis-photo-K.-Lilley-1024x576.jpg)

Members of the Charles Close Society at the site of first primary trigonometrical station in Ireland, Divis Mountain. (K. Lilley GAP)

About the Author:

Keith Lilley is Professor of Historical Geography at Queen’s University Belfast, with research interests in the history of cartography and the application of GI Systems for analysing historic maps, and also for creating new maps of historic landscapes. His most recent book is “Mapping Medieval Geographies”, published in 2013 by Cambridge University Press. He is working on a new book called “Sovereign Spaces”, on the place of surveying in medieval kingship, and is beginning a new project called “Surveying Empires: Archaeologies of Colonial Cartography”. He is a member of the Charles Close Society and Chair of the Historic Towns Trust.