Copycat Rhythms and Musical Gossip!

My placement at the Junior Academy of Music (JAM) has taught me the importance of facilitating an inclusive teaching environment as an educator. At the beginning of my experience, I assisted with the Green Group, a class of four to seven-year-olds with similar learning capabilities who were only beginning to explore the foundations of musicianship. However, I faced new obstacles this term as I began working with the Blue Group at JAM – a music education class for six to eight-year-olds designed to develop listening and performing abilities. In addition to adapting to new learning objectives for this age group, I had to overcome the challenge of teaching a mixed ability class.

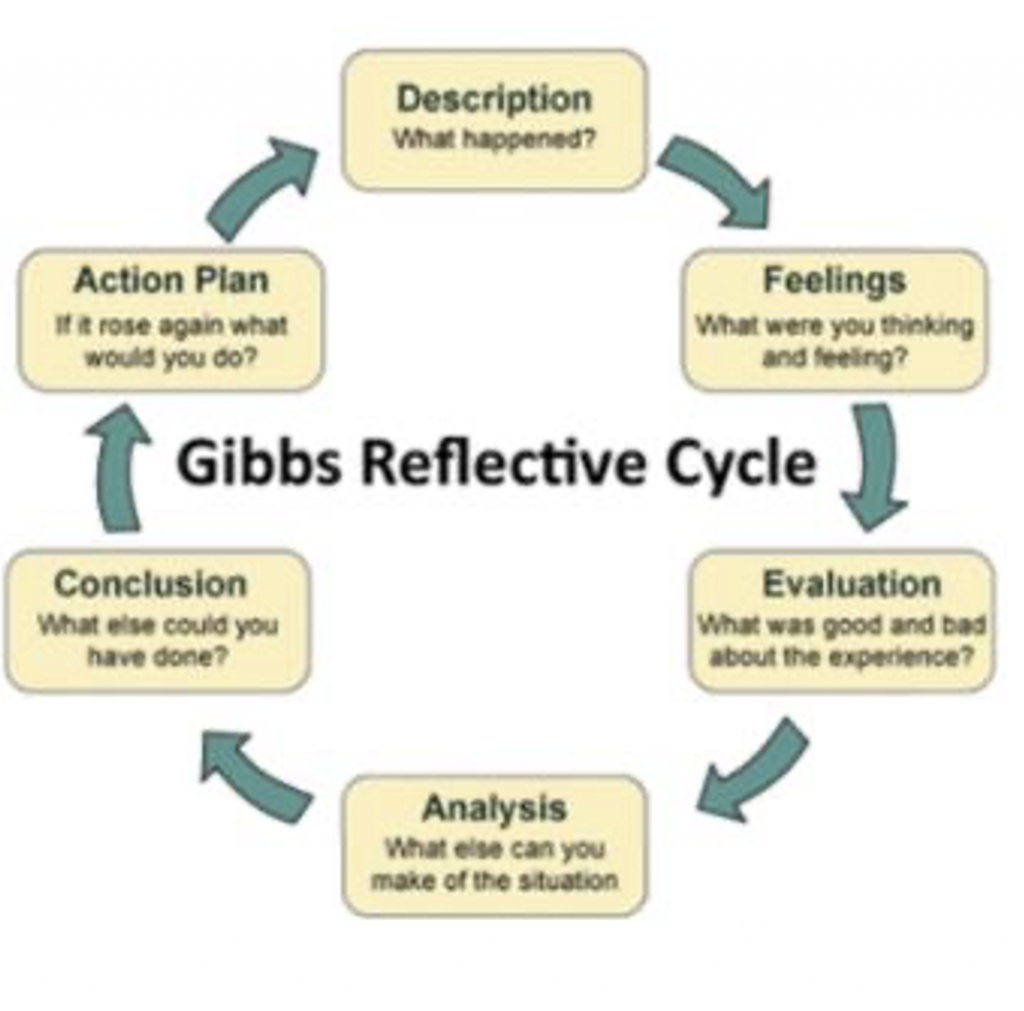

To effectively reflect and examine the challenging aspects of my work placement, I will use Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle (1988).

Upon initial observation, it became evident that the children had a variety of abilities and limitations. I noted that lower ability participants lacked the confidence to perform in groups, yet higher ability participants were unchallenged by teaching material and thus less motivated to learn. Some of the class also had physical impairments, with two of the children having confirmed diagnosis’ of cerebral palsy, a condition characterized by ‘paralysis, weakness, incoordination and any other aberration of motor function due to malfunction of the centers of the brain’ (Lefevre, M. 1960. p.59).

Reflecting on the range of physical impairments and learning abilities within the group, planning appropriate musical activities felt like a daunting challenge as ‘whilst music may be appropriated to reify positive signifiers of in-group identification, it can also emphasise marginality’ (Watts, M. and Ridley, B. 2012. p.354) and leave children feeling excluded. After examining each child and their learning style, I considered how the range of abilities would shape the overall lesson plan. I chose to retain the delivery of music education in a stimulating game format and decided to incorporate two exercises into the session; ‘Copycat Rhythms’ and ‘Musical Gossip’.

The ‘Copycat Rhythms’ exercise involves a group leader inventing rhythms for others to copy, with the overall aim of the activity to improve sequential memory and recall. To make the game easier, I initially used Kodaly-inspired rhythm syllables, a system that replaces the name of rhythmic values with simplistic syllables such as ‘ta’ and ‘ti’. Evaluating the system’s effectiveness, I noted how all children could internalize rhythms successfully, yet some failed to follow a regular beat when performing them back. To help with their sense of pulse, I replaced verbal chanting with untuned percussion instruments. Making this adaption not only aided those who struggled with musical entrainment to improve their skills, but the act of each child choosing their percussion instrument helped to maintain enthusiasm throughout the entire class and encouraged individual engagement.

The ‘Musical Gossip’ activity also helped develop each child’s rhythmic literacy within a group setting. The exercise involved everyone standing in a line, with the person at the end creating a rhythm and tapping it out on the person’s shoulder in front of them. The aim was to end with the same rhythm that the line began with, which fostered an environment where the children could work on their team-building skills together. Everyone took a turn standing at the back of the line and creating a rhythm to be passed on, allowing each child to effectively engage with the activity at their own level. Moreover, as the children were not facing each other, I found that those who struggled with confidence within a group gained self-esteem.

Analysing how ‘Musical Gossip’ helped establish an inclusive learning environment, each individual played a crucial role in the overall task. Despite the positive impact of the activity, I noticed that some of the children were very heavy-handed when tapping out the rhythms and had to be reminded to use ‘gentle hands’. On reflection, an activity that involves less physical contact between children may be more beneficial.

Examining how the ‘Copycat Rhythms’ exercise improved children’s engagement with physical impairments, using weighted sticks helped challenge proprioceptive hyposensitivity via ‘various muscle contractions taking place’ (Hooper, J., et al. 2004. p.18). Moreover, switching hands in drumming exercises was beneficial in ‘improving the efficiency with which the central nervous system interprets and uses sensory information’ (Hooper, J., et al. 2004. p.17). Additionally, as the experience incorporated a range of percussion instruments, I noticed how the children who initially struggled with mental focus became more attuned to their surroundings due to the rich sensory environment. Although the exercise was initially conducted in a group setting, I proceeded to ask each child to recall rhythms to me on a one-to-one basis. This personalised approach helped to address the range of individual learning needs, where rhythms delivered could be tailored to the difficulty levels of each child.

To summarize, I feel that I successfully selected and led the appropriate musical exercises that accommodated the diverse educational needs of the group. ‘Copycat Rhythms’ built on bilateral, hand, and fine motor coordination while also challenging children to retain task attention. On the other hand, ‘Musical Gossip’ helped improve abstract information processing and creative thinking. Nevertheless, both activities brought the group together through the discipline of music and kept each individual child stimulated to their level of learning. Reflecting on what I could improve on going forwards, I feel I need to become more attuned to how students are responding and ‘rely on real-time data and information to make decisions about what supports are most prudent’ (Barrett-Zahn, E., 2019. p.6). In brief, moments when conducting the individual ‘Copycat Rhythms’ I felt myself not reacting in the present to the raised needs of others around me. I aim to become more aware of decreases in other students’ engagement when conducting one-to-one exchanges and break up individual exercises with more group activities.

Bibliography

- Barrett-Zahn, E., 2019. Editor’s Note: Differentiated Instruction. Science and Children, 57(2), p.6.

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. London: Further Education Unit

- Hooper, J., McManus, A. and McIntyre, A. 2004. Exploring the Link between Music Therapy and Sensory Integration: An Individual Case Study. British Journal of Music Therapy, 18(1), pp.17-18.

- Lefevre, M., 1960. Language Problems of the Child with Cerebral Palsy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 25(3), p.59.

- Watts, M. and Ridley, B., 2012. Identities of dis/ability and music. British Educational Research Journal, 38(3), p.354.

Expect the Unexpected

You May Also Like

Patience is a Virtue

26 March 2022

Improvising like jazz

27 March 2022