Growth From Grunt Work: Learning the Ins and Outs of the Studio

“Learning about studio infrastructure whilst on placement breaks down a barrier to being able to work in the studio.”

This blog focuses on an unglamorous but important lesson I took from my placement, reflected on using the Gibbs model [1].

The Session Itself

I was assisting on the recording of a swing big band for the score of a local short film. This session took place early on in my placement and Covid restrictions still mandated at least 1.5m distancing – this was especially vital on this session as a significant portion of the band were over 75 and keen to be cautious. To be able to accommodate this the band were not able to be located in the main studio and were laid out one floor down in the Oh Yeah Centre gig venue. To do this the cabling was run through a hole in the floor of the control room and all the mics, stands, speakers and general recording infrastructure was brought down stairs from the main studio. Any adjustments or setup during the session required decisions to be made in the control room and then someone to run down one floor and make the changes on the ‘studio’ floor.

I am always happy and willing to get involved in and learn from the physical work of session set-up and take-down, but my main objective in my placement is to be able to observe and question the creative production decisions of the engineers I shadow. Because the band were not located in the studio I was looking forward to seeing how the engineer would adapt their process of mic positioning and the early stages of mixing to mitigate for a less than ideal acoustic space. I was keen to see how the engineer could incorporate the principals of building a studio such as those from Zager or Newell, in a temporary way to maximise the recording [2,3]. However, when the session started it became clear that the time pressure on the band to get 4 tracks recorded, as well as the demands of performers, band leader and the short film’s director on the attention of the engineer meant that I wasn’t going to be able to get many opportunities to try and dig down into the creative process without potentially being disruptive to the session flow.

Making The Most of a Learning Opportunity

To try and be of most use to the session, in light of how complex and busy it was, I turned my efforts to more of a ‘crew’ role, solving to focus on the practical adjustment and setup of the session on the ground floor while the engineer was in the studio control room on the first floor. I had a copy of the specification for each of the four tracks so that I could be running cabling and getting mics ready for the next session to prevent delays between recording passes. I could also make adjustments to mic positions when asked by the engineer and could fix broken cables, DI boxes etc immediately. Although this meant I could not observe directly the production process, it was important to facilitate the session running to time and maximise the rehearsal and performance time of the musicians. Although this was not necessarily what I went into the session intending to focus on, this made me acutely aware of the importance of session-infrastructure and smooth and quick changeovers between setup to maximise productivity. Paul Rutter discusses the importance of understanding how “industry roles fit together” in order to perform best in your own ideal role [4]. I feel like I benefitted greatly from focusing on time-management in this session and from the planning-mindset required to make sure one songs recording ran uninterrupted even though I was simultaneously preparing for the next song.

Preparing for a Freelance Career

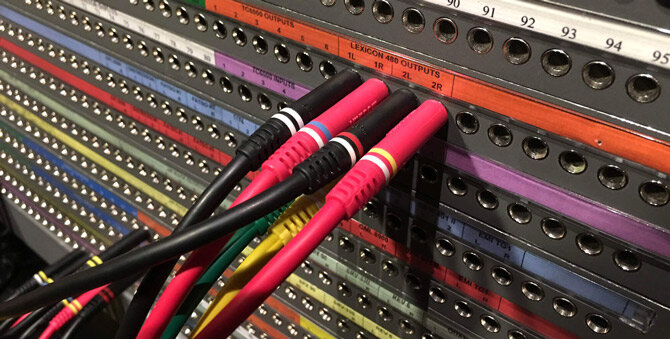

After all the tracks had been recorded the band’s conductor and the film’s director wanted to stay on in the control room to attend and contribute to the preliminary stages of the mix. I made the call to begin the takedown on my own in order to keep the control room clear and have the studio reset by the end of the day ready for the next day’s sessions. Through this whole session I took on a purely engineer role as opposed to focusing on production. This approach also gave me a chance to get a better knowledge of the signal flow in Start Together Studios. By doing take down on my now I could trace the signal path and was able to get to grips where cables a run through walls, how their patch bay works and examine typical analogue processing chains.

This is vitally important if I want to be a freelance engineer as economic changes in the industry have led to individual producers having to be solely responsible for all the technical operation of a recording, as examined in a study by Pras et al. in 2013 [5]. Signal flow has been featured heavily in learning for one of my other modules MUS3038 and so this was a chance to observe class material in a real-life setting. I hope to go on to work out of that studio as a freelancer after my time on placement. Learning about studio infrastructure whilst on placement breaks down a barrier to being able to work in the studio.

[1] Gibbs, Graham. Learning By Doing: A Guide To Teaching And Learning Methods. Oxford Further Education Unit, 1988.

[2] Zager, Michael. Music Production: For Producers, Composers, Arrangers, And Students. Scarecrow Press, 2011.

[3] Newell, Philip. Recording Studio Design, 4th Edition. Focal Press, 2017.

[4] Rutter, Paul. The Music Industry Handbook. Routledge, 2016.

[5] Pras, Amandine et al. “The Impact Of Technological Advances On Recording Studio Practices”. Journal Of The American Society For Information Science And Technology, vol 64, no. 3, 2013, pp. 612-626. Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22840.

The Student Production Manager

Patience is a Virtue

You May Also Like

Improvising like jazz

27 March 2022

Teamwork Makes the Stream Work

27 March 2022