The impact of overcrowding on prison rehabilitation and staff safety in Northern Ireland: A Briefing Paper

By Akanksha Chauhan – 3rd Year Undergraduate Student – Criminology

Introduction

Prison overcrowding in Northern Ireland is major issue that has detrimental effects on both staff safety and inmate rehabilitation (Arnold et al, 2012; Haney, 2015; Wooldredge et al, 2020). Around 1,877 inmates were housed in Northern Irelands prison system as of 2023/24, beyond the capacity of certain establishments (Department of Justice, 2023b). The largest facility, Maghaberry Prison, frequently runs over capacity, placing a strain on resources and creating overcrowding (Muirhead et al, 2020). These issues make it more difficult to obtain rehabilitation services that are essential for lowering reoffending rates, like education and job training (Geas, 1985). According to research, inmates in overcrowded facilities are much less likely to participate in these programs, which lowers their chances of making a full recovery (Haney, 2006).

The overcrowding in Northern Ireland’s prisons also poses a risk to staff safety (Haney, 2015). Ministry of Justice (2024) report shows the incidence of assaults on staff increased by 23% from the 12 months to June 2023 to a new peak in the 12 months to June 2024, with 118 assaults per 1,000 inmates (10,281 assaults on staff). This highlights how overcrowding exacerbates tensions, reduces control and increases violence in prisons. In addition to decreasing the effectiveness of supervision and increasing the likelihood of violence and self-harm episodes, overcrowding exacerbates relations between inmates and staff (Ministry of Justice, 2024). With regard to its sociopolitical dynamics, historical legacy and limited resources, Northern Ireland’s prison system has unique challenges (Lawrence, 2020). This briefing paper will examine the difficulties caused by prison overcrowding in Northern Ireland, as well as how it affects staff safety and rehabilitation initiatives. It will also look at possible legislative solutions to these problems.

Overcrowding in Northern Ireland’s prisons

Prison overcrowding in Northern Ireland is still a major issue (Muirhead et al, 2023b). In the last five years, the number of convicts has increased by 10%, reaching about 1,800 in facilities that can house about 1,400 inmates, according to the Northern Ireland Prison Service’s (NIPS) 2023 annual report (Department of Justice, 2023a). Department of Justice (2023b) report argues how the annual average reached its highest point since 2014–15 and it had been rising since 2020–21. The greatest high-security prison in Northern Ireland, HMP Maghaberry, is experiencing a particularly noticeable increase, running at 114% of its permitted capacity (Department of Justice, 2023a).

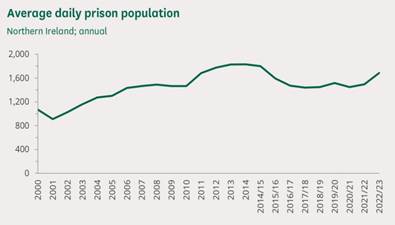

The average daily prison population since 2000 is displayed in Tabe 1. The series moves from calendar to financial year in 2014 (Department of Justice, 2023b). These patterns are consistent with a larger worldwide rise in incarceration rates, which is being fuelled by tougher sentencing guidelines, fewer non-custodial terms and more recidivism (Department of Justice, 2023b).

Table 1: Average Daily Prison Population

Source: UK Prison Population Statistics, 2023

Pre-trial detention, high recidivism rates and inadequate infrastructure investment are some of the interrelated causes of prison overcrowding in Northern Ireland (Gormally et al, 1993). With more than 40% of those who are released reoffending within a year, high recidivism rates draw attention to structural deficiencies in post-release assistance and rehabilitation initiatives (Department of Justice, 2023a). Prison facilities are overburdened by this cycle of imprisonment because available places are rapidly filled by repeat offenders (Haney, 2015). The use of detention to hold people while awaiting trial (also known as remand) makes the situation worse (Gormally et al, 1993). Inmates held on remand make up a sizeable portion of the prison population (King & Morgan, 2023). The misuse of custodial remand for non-violent offenders and inefficiencies in the legal system are frequently reflected in this practice (King & Morgan, 2023). Alternatives like electronic monitoring and bail are still underutilised, which needlessly adds to capacity constraints (Coyle, 2005).

The problem is made even worse by weak infrastructural investment (Coyle, 2005). Due to a lack of finance, existing jails are ill-equipped to manage the increasing number of inmates because new facilities cannot be built or modernised (Haney, 2015). When prisons are overcrowded, they frequently use shared cells as a way to absorb population pressures (Muirhead et al, 2023a). Since individuals are frequently compelled to share a small space against their will, cell-sharing is a varied experience. Cell-sharing, however, is by no means a novel occurrence (Muirhead et al, 2023b). There are worries that cell-sharing, which can take many different forms globally, compromises privacy, safety and dignity and causes distress and discomfort (Muirhead et al, 2023b). Prisons in Northern Ireland are reportedly operating at 11.4% over capacity, which reflects a structural inability to match supply with demand (Department of Justice, 2023b). Prisons in Northern Ireland are reportedly operating at 11.4% over capacity, which reflects a structural inability to match supply with demand (Department of Justice, 2023b).

Overcrowded prisons in Northern Ireland exacerbates serious problems and compromises the institutions’ ability to serve as safe and rehabilitative spaces (Lawrence, 2020). It overstretches logistical resources, resulting in worsening living circumstances marked by cramped living spaces, poor sanitation and a lack of medical treatment (Lawrence, 2020). Due to demand for limited resources like space, recreational activities and program possibilities, such circumstances promote interpersonal problems among prisoners (Wooldredge et al, 2020). These increased tensions make the prison atmosphere more unstable, which leads to more violent events (Wooldredge et al, 2020). Additionally, population growth limits the availability of resources that are necessary for rehabilitation and reintegration, such as mental health treatment, vocational training and education (Liebling & Arnold, 2004). For example, HMP Maghaberry’s congestion prevents fewer than half of eligible inmates from participating in rehabilitation programs, which feeds recidivism cycles (Department of Justice, 2023a). Therefore, overcrowding hinders the efficiency of the penal system in addition to dehumanising prison.

A multifaceted strategy that combines infrastructure expansion, judicial process acceleration and rehabilitation investment is needed to address these issues (Gaes, 1985; Santorso, 2024). A comprehensive approach is required to tackle prison overcrowding and rising violence, involving the expansion of prison facilities to reduce congestion, speeding up judicial processes to prevent unnecessary delays in hearing trials, sentencing or release and increasing investment in rehabilitation programs to address the root cause of criminal behaviour and reduce reoffending (Gaes, 1985; Santorso, 2024).

Prisoner rehabilitation

In order to promote effective reintegration into society, rehabilitation—which places an emphasis on offender change over punitive measures—plays a crucial role in contemporary correctional systems (Lipsey & Cullen, 2007). By addressing criminogenic needs, such as substance abuse, education deficiencies and mental health concerns, effective rehabilitation programs lower recidivism (Morgan et al, 2020; Andrews & Bonta, 2010). For instance, when properly used, cognitive-behavioural treatment has been demonstrated to reduce recidivism rates by as much as 25% (Lipsey & Cullen, 2007). Over 40% of people in Northern Ireland who are released from prison commit new crimes within a year, highlighting the critical need for all-encompassing rehabilitation programs (Department of Justice, 2023a).

By decreasing the need for incarceration and improving community safety, rehabilitation also lessens the wider social and financial consequences of crime (Andrews & Bonta, 2010). Programs that provide education, vocational training and drug rehabilitation give criminals the skills and resiliency they need to find work after being released from prison (Enell et al, 2022). Recidivism rates are below 30% in countries like Norway, where rehabilitation is given priority, while they are much higher in punitive systems (Enell et al, 2022). However, the availability and effectiveness of programs are restricted by overcrowding and underfunding in Northern Ireland’s prisons, endangering these advantages (Department of Justice, 2023b). In order to meet the rehabilitative mandate and achieve long-term societal gains, these hurdles must be addressed.

Overcrowding has been connected to tight prison social climates, higher rates of assault and bullying, as well as higher rates of suicide and self-harm, all of which make imprisonment more painful (Haney, 2012). Additionally, because overcrowding puts a burden on already few resources, it reduces opportunities for positive activities like training, education and mental health support (Muirhead et al, 2023a).

Muirhead et al (2023b) discovered that because cellmates can offer each other positive social and emotional support, healthy cellmate interactions may improve wellbeing beyond what is possible in a single cell. However, because of the stress people endure trying to hide their feelings and weaknesses, as well as their fears for their safety, it was also discovered that unsatisfactory cellmate interactions could negatively affect wellbeing beyond what is experienced in a single cell (Muirhead et al, 2023a). Muirhead et al (2023b) discusses how some people were especially fearful of being placed in a shared cell due to past experiences of abuse or because of characteristics, such as their sexual orientation, age or race, which may lead them to be vulnerable to bullying or exploitation. The establishment of relationships based on mutual respect may be facilitated by the successful negotiation of the shared cell space. This could shift people’s willingness to cooperate from merely following the bare minimum to lessen the inconveniences of cell-sharing to being inspired to modify their conduct out of consideration for their cellmate’s needs (Muirhead et al, 2023b).

Prison overcrowding in Northern Ireland also severely impairs rehabilitation by preventing inmates from accessing necessary services and activities. A disproportionate number of people are influenced by educational and occupational training, which are essential in addressing criminogenic variables (Morgan et al, 2020) Due to a lack of resources and capacity, only 45% of eligible inmates at HMP Maghaberry participated in rehabilitation programs during 2022 (Department of Justice, 2023b). Inmates’ mental health problems are further made worse by overcrowding, since overburdened healthcare systems are unable to keep up with the growing demand (Morgan et al, 2020; Lawrence, 2020).

It has been argued that overcrowding throws off structured routines; a lack of staff and facilities results in erratic timetables, less time spent outside and less opportunity to contact and interact with rehabilitation professionals (Haney, 2015). In addition to encouraging hostility and inactivity among prisoners, these disturbances jeopardise the stability required for successful reform (Coyle, 2005). Studies show that overcrowding exacerbates animosity and reduces the effectiveness of reoffending reduction strategies (Gaes, 1985; Santorso, 2024). Overcrowding undermines the fundamental goals of jail and perpetuates recidivism by limiting the delivery of rehabilitative programs and aggravating mental health crises (Haney, 2006). Investments in staffing, infrastructure, and evidence-based rehabilitation techniques are necessary to address this problem.

Staff safety and well being

Due to unstable and stressful working conditions caused by overcrowding, the safety and wellbeing of Northern Ireland’s prison employees are increasingly at danger (Butler, 2015). In line with the increasing number of prisoners, the Prison Officers’ Association recorded a 25% increase in assaults on staff from 2019 to 2023 (Prison Officers’ Association, 2023). Inmates’ frustrations are heightened in overcrowded facilities, which escalates disputes and puts staff members at more danger while conducting interventions (Liebling, 2004).

Officers are also subjected to excessive workload in this setting since their capacity to adequately handle emergencies is limited by low staffing ratios (Arnold et al, 2012). According to a Howard League for Penal Reform survey conducted in 2023, 40% of Northern Ireland’s prison employees reported having burnout symptoms as a result of working too much and being around violence. These circumstances compromise institutional stability by impairing work performance, rising absences and causing high turnover rates (Forman-Dolan et al, 2022).

To guarantee a safer, more sustainable workplace, overcrowding must be addressed with increased staffing levels and de-escalation training (Forman-Dolan et al, 2022), as prison staff play a crucial role in rehabilitation and desistance by acting as role models and encouraging inmate participation in rehabilitative programs. Increased inmate conflict, understaffing and staff burnout are the main causes of safety issues in overcrowded jails. Because of the increased competition for limited resources like food, shelter and medical care, overcrowding fosters violence (Forman-Dolan et al, 2022).

According to research, when tensions between inmates grow and affect officers, assaults on staff can increase in overcrowded jails (Gaes, 1985; Arnold et al, 2012)). With jails running at less-than-ideal officer-to-inmate ratios, understaffing makes these dangers worse by making it more difficult for staff to keep an eye on inmates and mediate disputes (Santorso, 2024). According to the Department of Justice (2023a), a lack of staff has resulted in less surveillance during crucial times, putting security at even greater risk.

Recommendations:

- Extend non-custodial sentencing. For non-violent offenders, increase the use of alternatives including electronic monitoring, community service and/or restorative justice.

- Change bail procedures. Encourage bail and other non-custodial measures to reduce the use of pre-trial detention.

- Fund Rehabilitation Initiatives to lower recidivism. Enhance post-release and in-prison initiatives to end the recidivism cycle.

- Improve the infrastructure and expand the capacity of prisons. To serve the current population, build new facilities or enlarge existing ones. Enhance current facilities by improving the infrastructure to better meet safety and rehabilitation requirements, particularly by adding areas specifically designed for therapy, education and enjoyment.

- Focus more on staff recruitment and retention. Provide competitive pay, benefits and chances for professional growth to address understaffing.

- Provide more mental health resources. Offer extensive programmes for staff well-being, such as stress management instruction and counselling.

- Provide better safety measures. Give staff with the tools, technology and training they need to handle disputes amicably.

- Enact systemic and policy reforms. Adopt laws based on effective global models, such as Norway’s emphasis on rehabilitation and compassionate prison conditions.

- Adopt frequent monitoring and evaluation to ensure ongoing progress. Conduct reviews of jail facilities, staffing levels and rehabilitation results on a regular basis.

Conclusion

In Northern Ireland, prison overpopulation poses serious problems for the efficacy of rehabilitation initiatives as well as the safety of correctional staff. The constant rise in the number of prisoners puts a burden on the few resources available, jeopardising rehabilitation efforts and raising the hazards for employees in these demanding settings. Immediate and focused effort is needed to address these problems in order to strike a balance between immediate relief and long-term improvement. While putting rehabilitation above punishment, the use of alternatives to jail, such as non-custodial sentencing, can lower the number of inmates.

Safety and morale can be raised at the same time by modernising jail buildings to house the present population and placing a strong emphasis on staff well-being through better working conditions, support networks, and sufficient training. These focused tactics can set the stage for significant change, even while structural improvements take time. Northern Ireland can develop a correctional system that strikes a balance between effectiveness and humanity by tackling the underlying causes of overcrowding and establishing secure, rehabilitative surroundings. This promotes a safer and more just society in addition to improving results for staff and prisoners.

Reference List

Andrews, D.A. and Bonta, J. (2024) The Psychology of Criminal Conduct, 7th ed. New York: Routledge.

Arnold, H., Liebling, A. and Tait, S. (2012) ‘Prison Officers and Prison Culture’, Handbook on Prison, pp.501-525.

Butler, M. (2015) ‘Prisoners and Prison Life’, The Routledge Handbook of Irish Criminology, pp.337-355.

Butler, M. (2020) ‘Using Specialised Prison Units to Manage Violent Extremists: Lessons from Northern Ireland’, Terrorism and political violence, 32(3), pp. 539–557.

Coyle, A. (2005) Understanding Prison: Key issues in policy and practice, 1st ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Department of Justice (2023a) ‘NI Prison Service Annual Report and Accounts 2022-23’, Available at: https://www.justice-ni.gov.uk/publications/ni-prison-service-annual-report-and-accounts-2022-23 (Accessed on 16 December 2024).

Department of Justice (2023b) ‘The Northern Ireland Prison Population 2023/24 Report’, Available at: https://www.justice-ni.gov.uk/news/northern-ireland-prison-population (Accessed on 16 December 2024).

Enell, S., Andersson Vogel, M., Henriksen, A.K.E., Pösö, T., Honkatukia, P., Mellin-Olsen, B. and Hydle, I.M. (2022) ‘Confinement and restrictive measures against young people in the Nordic countries–a comparative analysis of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden’, Nordic journal of criminology, 23(2), pp.174-191.

Forman-Dolan, J., Caggiano, C., Anillo, I. and Kennedy, T.D. (2022) ‘Burnout among Professionals Working in Corrections: A Two Stage Review’, International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(16), pp. 9954.

Gaes, G.G. (1985) ‘The Effects of Overcrowding in Prison’, Crime and justice, 6, pp. 95–146.

Gormally, B., McEvoy, K. and Wall, D. (1993) ‘Criminal Justice in a Divided Society: Northern Ireland Prisons’, Crime and Justice, 17, pp. 51–135.

Haney, C. (2012) Prison effects in the era of mass incarceration’, The Prison Journal, 1, pp. 1-24.

Haney, C. (2015) Prison Overcrowding, American Psychological Association.

Haney, C. (2006) ‘The Wages of Prison Overcrowding: Harmful Psychological Consequences and Dysfunctional Correctional Reactions’, Washington University Journal of Law and Policy, 22, pp.265-293.

Howard League for Penal Reform (2023) ‘Annual Report 2022-23’, Available at: https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Howard-League-for-Penal-Reform-Annual-Report-2022-to-2023-1.pdf (Accessed on 15 December 2024)

King, R.D. and Morgan, R. (2023) A Taste of Prison: Custodial Conditions for Trial and Remand Prisoners, Taylor & Francis: Routledge.

Lawrence, S.C.E. (2020) Inside Ageing: A Critical Review of Health and Wellbeing as Experienced by Older Men held in Custody in Northern Ireland, Thesis (Ph.D.) Queen’s University Belfast, Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences.

Liebling, A., & Arnold, H. (2004). Prisons and Their Moral Performance: A Study of Values, Quality, and Prison Life, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lipsey, M.W. and Cullen, F.T. (2007) ‘The effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation: A review of systematic reviews’, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 3(1), pp. 297–320.

Ministry of Justice (2024) ‘Safety in Custody Statistics, England and Wales: Deaths in prison Custody to September 2024 Assaults and Self harm to June.

Morgan, R.D., Scanlon, F. and Van horn, S.A. (2020) ‘Criminogenic Risk and Mental Health: A Complicated Relationship’, CNS Spectrums, 25(2), pp.237-244.

Muirhead, A., Butler, M. and Davidson, G. (2023a) ‘Behind closed doors: An exploration of cell-sharing and its relationship with wellbeing’, European journal of criminology, 20(1), pp. 335–355.

Muirhead, A., Butler, M. and Davidson, G. (2023b) ‘Surviving cell-sharing: Resistance, cooperation and collaboration’, Punishment & society, 25(2), pp. 500–518.

Muirhead, A., Butler, M. and Davidson, G. (2020) ‘“You can’t always pick your cellmate but if you can…. It is a bit better”: Staff and Prisoner Perceptions of What Factors Matter in Cell Allocation Decision-Making’, Kriminologie-Das Online-Journal| Criminology-The Online Journal, (2), pp.159-181.

Prison Officers Association (2023) ‘Annual report 2023’, available at: https://www.poauk.org.uk/media/2511/annual-report-2023-final.pdf

Santorso, S. (2024) ‘Harm and governance of prisons’ systemic overcrowding’, Oñanti socio-legal series, 1(1), pp.1-25.

Wooldredge, J., Sampson, R. and Petersilia, J. (2020) ‘Prison Culture, Management and in-Prison Violence’, Annual Review of Criminology, 3(1), pp. 165-188.