Suggestions for Policy Improvement in Immigration Detention – Marta Cipriano – 3rd Year Criminology & Sociology

Immigration detention can be understood as the practice of the Home Office in the United Kingdom (UK) to detain foreign citizens for immigration control while waiting for permission either to enter a country before they are deported or removed from said country (AVID, 2020; Silverman et al., 2021). It is essential to understand that immigration detention is an administrative process, not a criminal procedure. Therefore, migrants or undocumented individuals are detained at the decision of an immigration official, not a decision made by a court or judge (Detention Action, 2019; AVID, 2020). There are various policy reasons for detention, such as removal of the individual from the country; to establish identity or the basis of their immigration or asylum claim; where there is the risk of escape if released on bail; or when released, could be a risk to the public good (Silverman et al., 2021). It is also important to note that these centres are also used before removing people from EU countries and beyond who have a criminal record (Home Office, 2022). Therefore, there are not just asylum seekers but also people from foreign countries who are to be removed as either they have a criminal record (independent of whether they have served time) or have just finished serving their time (Home Office, 2022).

Unlike the rest of Europe, the UK does not limit how long individuals can be kept in detention centres. However, this does not apply to pregnant women with a limit of 72 hours (although a government minister can extend this to a maximum of seven days) (Silverman et al., 2021). There have been serious issues raised, such as mental health issues around the lack of time limit (Coffey et al., 2010; Bathily, 2014; von Werthern et al., 2018; Sen et al., 2018; Detention Action, 2019). The Home Office policy states that detention must be used sparingly, and for the shortest period possible, yet approximately 30,000 men, women, and children are held in detention every year (Silverman et al., 2021). Issues associated with detaining centres have only been exacerbated by the asylum and refugee ‘crisis’, which has been further affected due to COVID-19 (Silverman et al., 2021). This briefing paper will examine the extent and condition to which immigration detention centres detainees are treated in the UK. This paper will examine how the UK has changed in the last decades regarding their immigration policies, followed by detention centres present in the UK. Secondly, facts about immigration detention in the UK will be closely analysed, such as the breakdown in numbers and trends in the last decade in England and Northern Ireland. Following this, attention is paid to vulnerable individuals, such as those with mental health issues and those at a vulnerable age or part of LGBTQIA+, and how being detained affects them. Lastly, considering policy recommendations are proposed, taking international examples as the basis and how they can be adjusted and adapted into UK policy.

Understanding Policy

Asylum is protection granted by the government to an individual who has left their country to escape the threat to their life or liberty, such as those coming from countries in which wars are happening; these individuals are called refugees once asylum is granted (UNHCR, 2010; Walsh, 2021). In Europe, the UK and France are the only two countries that do not have policies in practice to support asylum seekers in following the Reception Conditions Directive. These reception conditions grant access to housing, food, clothing, health care, education for minors and access to employment with a maximum waiting period of 9 months after their application, with the UK having the longest waiting time of 12 months (Martín et al., 2016; European Commission, 2021). Before 2002, asylum seekers could apply for permission to work after waiting six months for the first decision on their application. However, in that same year, this provision was withdrawn, and no new policy was developed until February 2005. This policy introduced the period of a 12-month wait before being able to apply for a working permit and has since been reviewed, but to no avail of a shorter period; this later became the Immigration Act 2016, still imposing several restrictions on applicants (Refugee Action, 2020).

In the UK, as of June 30th 2021, there were 12 Immigration Removal Centres (IRCs) and Short-Term Holding Facilities (STHFs). Furthermore, there are various Pre-departure Accommodation Facilities (PDAs) and Short-Term Holding rooms based at ports of entry (Silverman et al., 2021). The only centre in Northern Ireland is Larne House STFH which can hold up to 19 men and women (GOV.UK, 2021). However, as it is a short-term holding facility, it does not hold individuals for longer than a period of 7 days. Therefore, if any person needs a longer period of detention, they are shipped to Scotland and England (Law Centre NI, 2018).

Numbers in Immigration Detention Centres in the UK

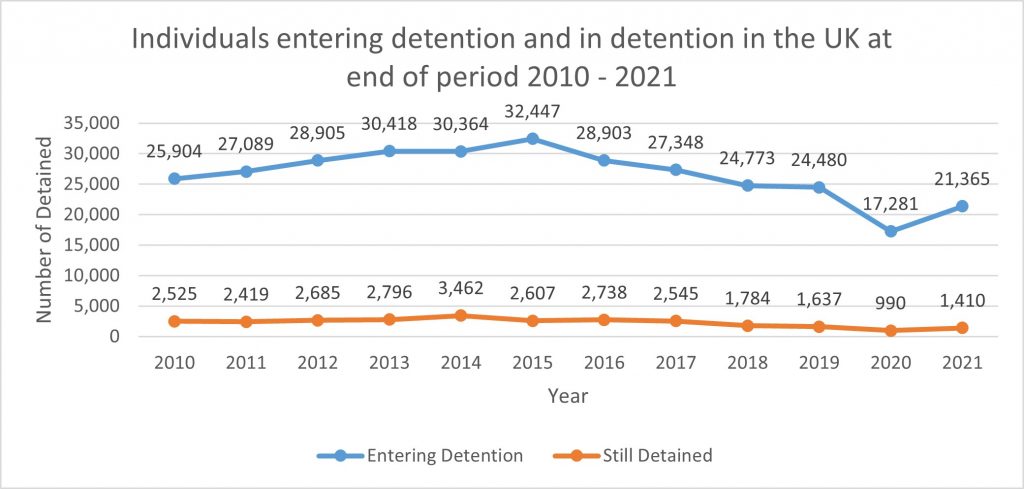

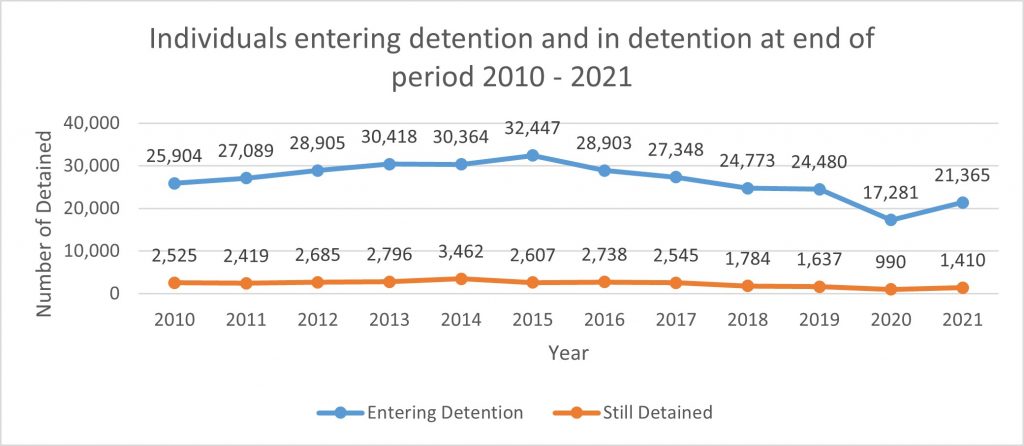

The graph below shows the overall entry of individuals into UK detention centres at the end of each period from 2010 to 2021. Very visibly, there was a consistent increase from 2010 to its peak in 2015 with 32,447 individuals, specifically a 25.25% increase. After that, there was a consistent decline reaching the lowest intake in 2020 with 17,281 individuals. This low peak is due to COVID-19 and a time where restrictions limited intake, but very visibly, that does not apply in 2021, where until July, when the data was published, there was an intake of 21,365 individuals. Unlike the blue line of intake, the orange line of those still detained at the end of each year does not visibly change massively. A decrease can be witnessed in 2020, but realistically, there is a decrease of 60.7%, whereas, for the total intake, there was a decrease of 33.2%; however, the change is more notable due to the sheer number being much bigger.

Data gathered from (GOV.UK, 2021)

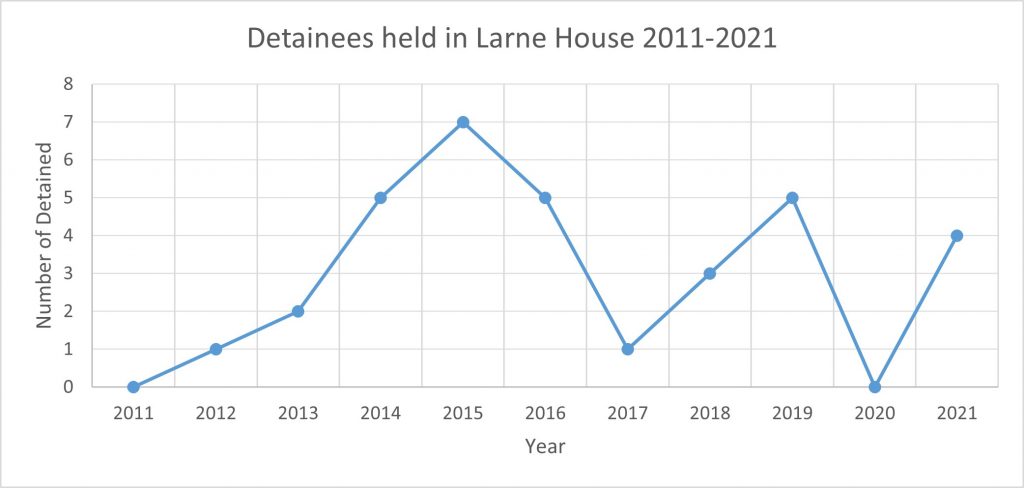

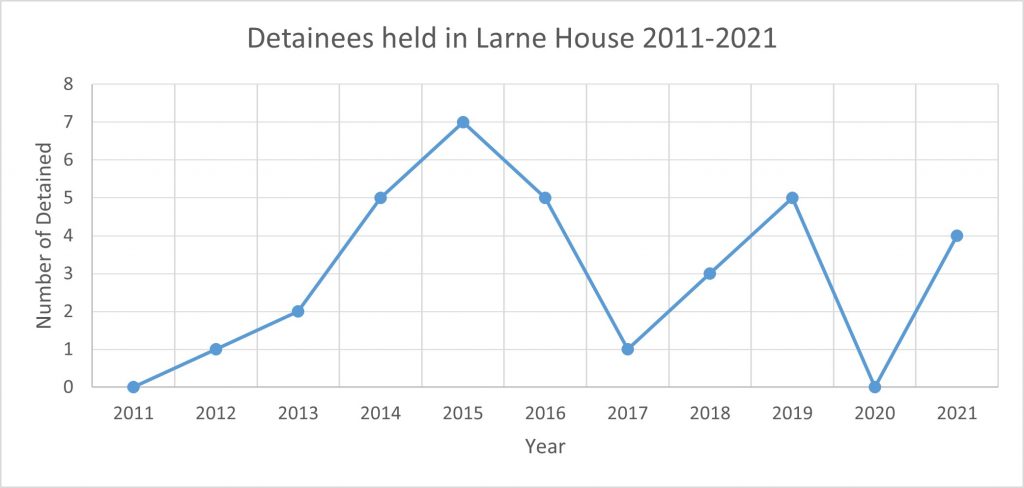

In Northern Ireland (NI), as seen below, there has been a fluctuation in the occupation of Larne House. Records have been kept since 2011 when the Larne House unit opened. In 2015 it recorded the highest number of detained individuals at any one time, 7. By 2017 it dropped back down to 1, although it is unclear whether it was due to the individuals being released, deported, or sent to a long-term facility. Since COVID-19 hit in 2019/2020, immigration detention in the UK significantly reduced (Silverman et al., 2021), hence the value of zero individuals detained in 2020, then four individuals once detention resumed. Those currently held are all male, ranging between 18-69, and come from Syria, Romania, Albania, and Lithuania (GOV.UK, 2021).

Data gathered from (GOV.UK, 2021)

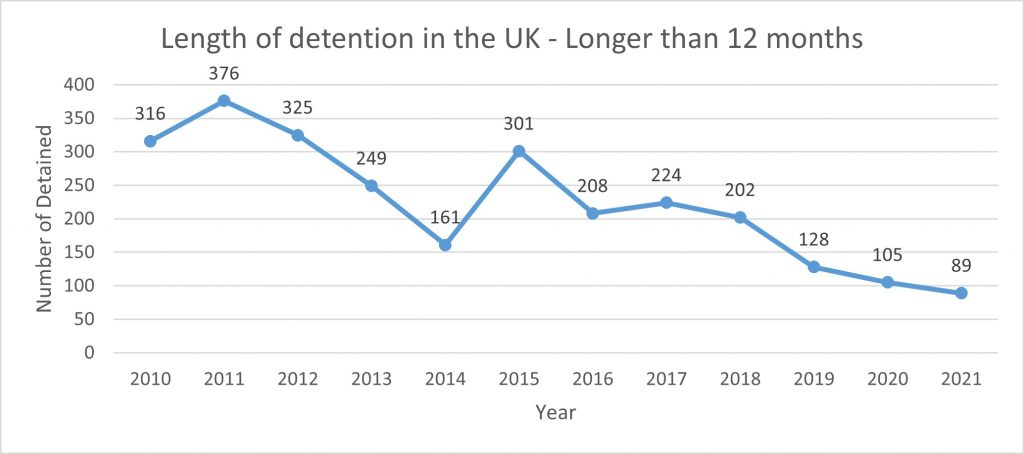

Lastly, below is a graph showing the trend of those detained for longer than 12 months in the UK. The visual aid of the graph illustrates that the decline is imminent, showing a 66.7% drop which is very positive but not enough. Considering there are severe negative impacts on an individual’s well-being, it is fundamental that those detained are done so as a last resort and for the shortest time possible. However, that is not happening, considering there are individuals consistently remaining in detention for longer than 12 months. Even though there is a decline, it is not evident whether it is through deportation, asylum accepted, or transfer to another detainment method such as a prison. Unlike the graphs above, there is a consistent decline from 2017. Although statistics for 2021 are also lower than 2020, during COVID-19 and detention limitations, the statistics are only taken up to quarter 3 of the year, equivalents to September, possibly explaining the small number.

Data gathered from (Neal, 2021; Silverman et al., 2021)

Mental Health of Detainees

Many countries have faced criticism concerning the conditions of their detention centres and the lack of time limits on stays. Further, extensive research has found that immigration detention causes psychological harm. This has been found to cause high rates of depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Coffey et al., 2010; British Medical Association, 2017; Sen et al., 2018; Von Werthern et al., 2018). In STHF, detainees have the right to be medically screened by a healthcare professional within the first 2 hours of admission, whereas for those in IRCs, there is a 24-hour period (Home Office, 2018; Home Office, 2021). In addition, detainees are entitled to the same level and quality of services as the general public. In Northern Ireland and Scotland, this service is the responsibility of service providers such as Social Health Care trusts. In England, the National Health Service (NHS) is responsible for healthcare for those in IRCs (British Medical Association, 2017). However, there are various issues when it comes to the provision of these services; for detainees with complex needs, it is questioned if their needs can be met in an environment like a detention centre, and with issues, the healthcare system suffers such as waiting times, staff shortages, and availability of services Medical Justice, 2016; British Medical Association, 2017). With all these issues and lack of resources, detainees’ suffering is being exacerbated. Recent figures published in the Shaw Review Report suggested that at least 30 detainees were on constant watch every month, at risk of self-harm and suicide (Shaw, 2018). Detainees on watch and at higher risk are placed on a risk reduction procedure known as Assessment and Care in Detention and Teamwork (ACDT) (HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, 2018; Briffa et al., 2021).

Vulnerable Individuals

The Adults at Risk (AAR) policy was implemented in 2016 by the Home Office to address previous reports (Shaw, 2016) of multiple failings identified and aimed to “lead to a reduction in the number of vulnerable people detained and a reduction in the duration of detention before removal” (Brokenshire, 2016; BiD, 2018). When an individual is detained as an ‘AAR’, they declare they “suffer from a condition, or have experienced traumatic events such as trafficking, torture or sexual violence” (Home Office, 2021, p. 6). Furthermore, risk factors determine who is most vulnerable, including disabilities, mental health issues, age (anyone over 70), pregnant women, LGBTQIA+ individuals, and being a minor (Home Office, 2021). Once someone has been classified as ‘at risk’, all the evidence should be gathered and analysed to determine the availability of support and whether or not detainment is the best and safest option for them (Home Office, 2021).

Policy Recommendations

For possible future improvements, policy recommendations that can be revised and adapted are suggested, including aspects such as detention centre conditions and more aid to help asylum seekers and refugees in most dire need. These recommendations are stated below and explain how they can be further developed. It also shows how similar international policies and schemes have proven successful in the past and how research has been seen to aid these recommendations.

- Applying a time limit to UK Detention Centres: Under article 9(1) of the ‘International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), every person has the right to liberty, and no one should be subjected to unmotivated detention (United Nations Human Rights, 1976; Majcher, 2019). The UK is the only country in the world that does not have a detention time limit (Cambridge Econometrics, 2019; Refugee Action, 2020), and so there have been various proposals to introduce a 28-day time limit to UK immigration detention (The Detention Forum, 2018; Cambridge Econometrics, 2019; Detention Action, 2019; The Detention Forum, 2020). It has been extensively researched that detention has negative mental health effects beyond the time spent in detention (Pourgourides, 1997; Steel et al., 2006; Triggs, 2013), so implementing a time limit on detention would be beneficial. Furthermore, international research has demonstrated feelings of hopefulness, determination, and co-operation from detainees when knowing they have a limit on how long they can be detained in those conditions (Refugee Action, 2020).

- Right to work and benefits: Working and receiving benefits in the UK is only permitted after 12 months after applying for international protection, leaving deprived individuals and families on a mere £5.66 a day (£39.63 a week), which is not always granted (Walsh, 2021). Giving asylum seekers the right to work would benefit many aspects such as the economy and well-being. Allowing the right to work could benefit the UK economy by £97.8 million per year and further improve personal aspects such as mental health, dignity and integration (Refugee Action, 2020). Countries such as Ireland state that asylum seekers have the right to apply to work through the Labour Market Access Permission, which can be done if the individual has been waiting for longer than five months for their asylum seekers’ application to have been given first decision (Citizens Information, 2021). Countries such as Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Italy have experienced exponential economic and well-being improvements by allowing asylum seekers to work as little as two months after applying for international protection (Italy) (Martín et al., 2016). In addition, countries such as Canada and Australia encourage individuals from the moment of detainment to start looking for work and exploring their options depending on their visa type. Overall improve relationships and attitudes toward the future among the general public and detainees (Refugee Lives, 2018; Kweider, 2018; Refugee Action, 2020). With so much research and experience from other countries benefitting from these individuals being legally allowed into the labour market, UK policy must be reviewed and changed.

- Alternatives to Detention: The person’s right to liberty and security is fundamental in core international human rights laws (Human Rights and Migration, 2017). By the UK’s lack of time limit, these core human rights are disregarded. Detention should be reserved for individuals who pose a threat to society; even then, detention should be replaced with humane monitoring (British Medical Association, 2017). More recently, in the UK, after international experience and consistent research demonstrating the negative impact on detained individuals, the Immigration Minister states there have been development trials on alternatives to detainment, especially to promote and encourage voluntary returns, a 30% reduction of detained immigrants, and an increase in face-to-face engagement with detainees, and improved contact between them and their caseworkers (GOV.UK, 2019). In addition, there have been other pilot projects such as those provided by Action Foundation, including; Action Housing, Action Language, Digital Inclusion, and Action Access (Action Foundation, 2021). Throughout those different projects, they give free English classes, free training and provision on how to use basic technology devices, and accommodation provisions for those asylum seekers that have been denied asylum (Action Foundation, 2021). In 2017, the council of Europe released a report on Human Rights and Migration, covering aspects such as immigration, detention, and alternatives. This report includes alternatives used internationally, such as registration with authorities, temporary residence permits, regular reporting, and designated residences (Council of Europe, 2017). Looking at how successful and innovative these have done internationally, it would be beneficial for the UK to review their policies and implement some of these alternatives.

Through extensive research internationally, it has been proven on multiple occasions that the UK could implement international laws and requirements regarding immigration detention and those detained. This report fundamentally explored those and demonstrated the potential benefits of adopting international law in the UK and NI, including successful trials and studies. For future studies, implementing these recommendations could be benefitial to monitor the impact they would have on UK and NI and see if they compare, and if certain aspects of these laws and regulations can be further adapted and changed for the benefit of those affected.

References

Action Foundation (2021). Projects. Available at: https://actionfoundation.org.uk/projects/ [Accessed 7 December 2021].

AVID (2020). What is immigration detention?. Available at: http://www.aviddetention.org.uk/immigration-detention/what-immigration-detention [Accessed 29 November 2021].

Bathily, A. (2014). Immigration detention and its impact on integration – A European approach -, Milan: ISMU Foundation.

BiD (2018). Adults at risk: the ongoing struggle for vulnerable adults in detention, London: BiD.

Briffa, K.,Chaplin, L., Daoud, R., Egan, S., Fairweather, S., Grant-Peterkin, H., Harris, K., Hassan, R., Katona, C., Leidecker, M., Majid, S., Mounty, J., Ng, L., Pillay, M., Pushkar, P., Schleicher, T., Sen, P., Stern, M., Turner, F., Waterman, L. (2021). Detention of People with Mental Disorders in Immigration Removal Centres (IRCs), London: The Royal College of Psychiatrists.

British Medical Association (2017). Locked up, locked out: Health and Human Rights in Immigration Detention, London: British Medical Association.

Brokenshire, J. (2016). Immigration Detention: Response to Stephen Shaw’s report into the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable Persons: Statement made on January 14th 2016. Available at: https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2016-01-14/HCWS470 [Accessed 1 December 2021].

Cambridge Econometrics (2019). Economic impacts of immigration detention reform, Cambridge: Cambridge Econometrics.

Citizens Information (2021). Direct Provision System. Available at: https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/moving_country/asylum_seekers_and_refugees/services_for_asylum_seekers_in_ireland/direct_provision.html [Accessed 6 December 2021].

Coffey, G. J., Kaplan, I., Sampson, R. C. & Tucci, M. M. (2010). The meaning and mental health consequences of long-term immigration detention for people seeking asylum. Journal Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), pp. 2070-2079.

Council of Europe (2017). Human Rights and Migration, Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Detention Action (2019). A 28 day statutory time limit on immigration detention: The Cross-Party Time Limit on Immigration Detention Amendment to the Immigration and Social Security Coordination (EU Withdrawal) Bill, London: Detention Action.

European Commission (2021). Migration and Home Affairs. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/policies/migration-and-asylum/common-european-asylum-system/reception-conditions_en [Accessed 6 December 2021].

GOV.UK (2019). Immigration detention reform. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/immigration-detention-reform [Accessed 7 December 2021].

GOV.UK (2021). Immigration statistics data tables, year ending September 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/immigration-statistics-data-tables-year-ending-september-2021 [Accessed 1 December 2021].

GOV.UK (2021). Returns and detention datasets. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/returns-and-detention-datasets [Accessed 1 December 2021].

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons (2018). Report on an Unannounced Inspection of the Larne House, London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons.

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons (2019). Report on an unannounced inspection of Morton Hall Immigration Removal Centre, London: HM Inspectorate of Prisons.

Home Office (2018). Short-Term Holding Facility Rules 2018, London: Home Office.

Home Office (2021). Adults at risk in immigration detention, London: Home Office.

Home Office (2021). Detention: General Instructions, London: Home Office.

Home Office (2022). Detention: General Instructions, London: Home Office.

Human Rights and Migration (2017). Legal and practical aspects of effective alternatives to detention in the context of migration, Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Law Centre (NI) (2018). JCHR: Inquiry into Immigration Detention, Belfast: Law Centre (NI).

Majcher, I. (2019). Immigration Detention under the GlobalCompacts in the Light of Refugee andHuman Rights Law Standards. Journal of International Migration, 57(6), pp. 91-114.

Martín, I. et al. (2016). From Refugees to Workers: Mapping Labour Market Integration Support Measures for Asylum-Seekers and Refugees in EU Member States., Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Medical Justice (2016). Provision of Healthcare in Detention. Available at: http://www.medicaljustice.org.uk/healthcare-in-detention/provision-of-healthcare-in-detention/ [Accessed 8 December 2021].

Neal, D. (2021). Second annual inspection of ‘Adults at risk in immigration detention’, London: Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration.

Pourgourides, C. (1997). A Second Exile: The Mental Health Iplications of Dtention of Aylum Seekers in the UK. Psychiatric Bulletin, 21(1), pp. 673-674.

Refugee Action (2020). Lift the Ban: Why giving people seeking asylum the right to work is common sense, London: Refugee Action.

Sen, P. et al. (2018). Mental health morbidity among people subject to immigration detention in the UK: a feasibility study. Journal of Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(1), p. 628–637.

Shaw, S. (2016). Review in the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable Persons, Westminister: Secretary of State for Home Department.

Shaw, S. (2018). Assessment of Government Progress in Implementing the Report on the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable Persons, Westminister: Secretary of State for Home Department.

Silverman, S. J., Griffiths, M. B. E. & Walsh, P. W. (2021). Immigration Detention in the UK, Oxford: The Migration Observatory.

Steel, Z. et al. (2006). Impact of Immigration Detention and Temporary Protection on Themental Health of Refugees. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(1), pp. 58-64.

The Detention Forum (2018). Why a 28 day time limit on immigration detention?, London: The Detention Forum.

The Detention Forum (2020). Time Limit for Immigration Detention, London: The Detention Forum.

Triggs, G. (2013). Mental Health and Immigration Detention. The Medical Journal of Australia, 199(11), pp. 721-722.

UNHCR (2010). Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, Geneva: UNHCR.

United Nations Human Rights (1976). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Geneva: United Nations Human Rights.

von Werthern, W., Robjant, K., Chui, Z., Schon, R., Ottisova, L., Mason, C., Katona, C. (2018). The impact of immigration detention on mental health: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(382), pp. 1-19.

Walsh, P. W. (2021). Briefing: Asylum and Refugee Resettlement in the UK, Oxford: The Migration Observatory.

Appendix

Graph 1: Detainees held in Larne House 2011 – 2021

Graph 2: Individuals entering detention and remaining in detention at the end of period: 2010 – 2021

Graph 3: Individuals detained for longer than 12 months in the UK: 2010 – 2021