Policy Review: National Disability Strategy

Grace Tobin – 2nd Year Undergraduate Student – Anthropology

Introduction

This policy review will focus on autism and underemployment due to autistic people being the most underemployed demographic, having both the widest pay gap and unemployment rate (ONS, 2021b; ONS, 2023a; ONS, 2023b; ONS, 2021a; NAS, 2021; NAS, 2016; ONS, 2021a). This article will firstly examine the National Disability Strategy (NDS)’s policy issues, and secondly how these issues are addressed. Then it will discuss why autistic people are underemployed (likely due to job interviews, meltdowns/shutdowns, transport to work, mental health support, ableism and reasonable adjustments) examined under the section “Critical Analysis of Policy Responses” addressed under their specific headings. This policy review will examine the reasoning behind the policy, an exploration of it and its strengths and weaknesses before concluding.

Capitalism is private ownership of the means of production (Bellanca, 2013). Under capitalism, the vast majority of people must sell their labour in exchange for wages to a small number of people who own the means of production and natural resources (Bellanca, 2013). This creates an “asymmetrical power dynamic” (Bellanca, 2013). This makes being employed tied to one’s self-worth (Wegscheider & Guevel, 2021). Employed individuals have an increased sense of belonging, reduced anxiety and better overall mental health, while in contrast, unemployed individuals have increased anxiety and depression (Wegscheider & Guevel, 2021).

The capitalistic economy and the way it exploits the physical and intellectual labour of workers contributed to what one understands what disability means (Slorach, 2016). The ancient Greeks and Romans had words for specific impairments such as ‘blind’ or ‘deaf’ but not disabled or disability (Slorach, 2016). After the fall of the Roman Empire in Europe, people with impairments were looked after by their families and if they were not, they were cared for by monks and nuns (Slorach, 2016). Capitalism and industrialisation of the Georgians and Victorians meant that work became time-orientated rather than task-orientated making it more difficult for people with certain bodies and brains to work and thus these people were sent to asylums and workhouses, segregated from wider society (Slorach, 2016). This created the modern concept of disability (Slorach, 2016). Another reason for its creation was that colonial forces constructed a hierarchy among people by labelling Indigenous peoples as inferior and incapable of self-governance (Kemp & Schweitzer, 2024). This hierarchy justified their exploitation and dehumanisation, falsely justifying that they were unworthy of the same rights and privileges as their colonisers (Kemp & Schweitzer, 2024).

This means disabled people are far less likely to be employed, yet under capitalism, one’s job is tied to one’s self-worth and thus employment increases one’s mental wellbeing and for disabled people it is also tied to social inclusion (Wegscheider & Guevel, 2021). Grassroots disability activism led to the “Disability Discrimination Act (1995)” thus making ableism illegal in employment (and other areas) in the United Kingdom (UK) (Oliver, 1990; Slorach, 2016). Also disabled people have the United Nations right to employment (UN – Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Social Inclusion, n.d.). However, the “Disability Discrimination Act (1995)” is based on the outdated medical model, which states that disabled people are disabled because they have medical conditions (Slorach, 2016; Oliver, 1990).

The National Disability Strategy (NDS) was created on the 25th anniversary of the Disability Discrimination Act and appears to be centred on the social model of disability (Disability Unit, et al., 2021). This model states that disabled people are disabled by barriers placed by society and focuses on tackling ableism by removing them (Oliver, 1990).

The NDS is important for contemporary society as the increasing diagnostic rate for autism (787% between 1998 and 2018), particularly among marginalised genders (Russel, et al., 2022) and races means more people are directly affected by this policy. Even then, autism is believed to be underdiagnosed, O’Nions et al (2013) estimate that 0.77-2.12% of the English population may be underdiagnosed (58.63- 72.11% of the English Autistic population). The waiting list to receive an autism diagnosis in Northern Ireland is currently so long that measures are being implemented to reduce it (Department of Health, 2024). Autistic people are still underemployed whether they are formally diagnosed or not.

Understanding the Policy Issue(s)

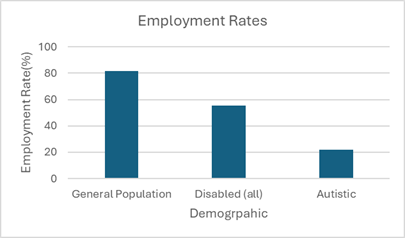

In 2021, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) published that only 22% of working-age autistic people are employed, which was lower than the National Autistic Society’s (NAS) previous estimations (NAS, 2021). This is lower than the employment rates of disabled people in general, 55.3% compared to 81.6% for non-disabled people (ONS, 2021a). The author has illustrated these statistics in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Employment rates for Autistic people compared to the general population and the general disabled population in the UK

Figure 1: Data from ONS, 2021b; ONS, 2023a; ONS, 2023b.

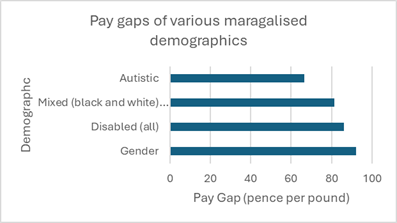

Employed autistic people are paid 66.5p for every pound an allistic (non-autistic) employee makes (ONS, 2021b; ONS, 2023a; ONS, 2023b). This is the largest pay gap in the UK, wider than the race, gender and general disability pay gaps (ONS, 2021b; ONS, 2023a; ONS, 2023b). The author has illustrated these statistics in

Figure 2 – The pay gaps of various marginalised demographics in the UK

Figure 2: Data from ONS, 2021b; ONS, 2023a; ONS, 2023b.

Addressing the Policy Issue(s)

There is a lack of research on disability policies because “disability is not an area which has tended to attract much attention from political scientists” (Evans, 2023, p. 1746).

In 2010, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government introduced welfare reform which cut benefits in response to the 2008 financial crisis (UNISON, 2013). According to UNISON (2013, p1) “no group [was] affected more than disabled people.” Consequently, more disabled people must seek employment to meet the cost of living. This led to widespread protests and the formation of the activist group Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC) (DPAC, o/b 2011).

According to Evans (2023) since the global financial crisis in 2008 there has been a lack of focus on disability policies in election manifestos until Jeremy Corbyn was elected Labour Party leader in 2015. Even then, disabled people were still omitted from the process, especially by the Conservative Party (Evans, 2023). Evans (2023) believes that disability policies from both parties could be described as “piecemeal” (p.1744).

With this in mind, both political Great British parties, the Conservative and Labour, made promises to improve disability rights on their manifestos for the 2017 election, though Labour made more (Evans, 2023). The Conservatives won the 2017 election (Baker, et al., 2019) and implemented the National Disability Strategy (NDS), which has a section on employment (Disability Unit, et al., 2021). Labour won the election in July 2024, and it is not yet clear what their policy will be (Cracknell, et al., 2024) .

Critical Analysis of Policy Responses

This section provides a critical analysis of the underemployment of autistic people. It evaluates whether the NDS response will reduce the underemployment of autistic people. There is a lack of critical analysis of the policy directly, especially for autistic people.

Job Interviews

When autistic people attend job interviews, interviewers often inform autistic candidates that they are too blunt and honest (Finn, et al., 2023). This is a societal problem as during the Middle Ages, autistic people were admired for these exact qualities as ‘natural fools’, referred by Chevreau (1994, p. ii) as ‘the sage’ (Carpenter, 2020). Job interviews require one to make a good first impression, but studies have shown that neurotypical people are likely to have a negative first impression of autistic people (Sasson, et al., 2017; DeBrabander, et al., 2019). In addition, interviews are made difficult because of the ‘double empathy problem’, where autistic-allistic communication breaks down more often compared to allistic-allistic or autistic-autistic communication (Jones, et al., 2023). Therefore, autistic people often perceive job interviews as a test of allistic social skills and feel forced to mask, i.e. hide their autistic traits which has negative impacts on autistic people’s mental health, including burnout and suicidal thoughts (Finn, et al., 2023; Pearson & Rose, 2021).

The NDS does little to address this problem, except guarantee disabled people an interview when they apply for jobs that they meet the requirements for (Disability Unit, et al., 2021). Instead, it could make employers more aware of how disabled people can appear during job interviews, offer alternatives or adjustments such as work trials or knowing the questions beforehand.

Meltdowns and Shutdowns

Autistic people often have meltdowns or shutdowns (Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust, n.d). Meltdowns occur when an autistic person becomes overwhelmed, loses control of their behaviour and can express themself no other way than shouting, growling or crying; or kicking and flapping (Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust, n.d). Shutdowns also occur when an autistic person is overwhelmed by the same triggers, but the autistic person can find it difficult to speak and may want to hide away (Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust, n.d).

While meltdowns/shutdowns have triggers that vary among individuals, they can occur anytime, even before they are due to arrive at work. Even when meltdowns/shutdowns have stopped, they still feel overwhelmed, fatigued, guilty and full of self-hate (Lewis & Stevens, 2023).

Furthermore, meltdowns/shutdowns are one of the most stigmatised aspects of autism, being seen as ‘challenging behaviour’ and labelled as ‘temper tantrums’ (Lewis & Stevens, 2023). Studies of meltdowns tend to focus on the impact it has on observers rather than the individual (Lewis & Stevens, 2023). This may cause a strain in autistic people’s relationships with their co-workers or boss if they are late because of a meltdown/shutdown. It is therefore beneficial for autistic employees to have the option to work from home due to both the social and physical consequences of a meltdown or shutdown, as well as being forced to deal with the unwritten social rules, which are utilised in the NDS (Disability Unit, et al., 2021). Employers however should be careful not to stereotype autistic people as preparing to work from home (Grella, et al., 2022).

Transport to Work

There is limited research on autistic people’s ability to use certain forms of transport. The research that does exist will be presented below.

Various skills are used in transport and journeys that a neurotypical person is likely unaware they are using (Mackett, 2017). For all journeys made, a person must remember and understand information, make decisions based on this information, communicate with others and understand social norms and rules (Mackett, 2017). This can be difficult for autistic people due to executive dysfunction and not understanding allistic social rules and norms (Song, et al., 2023; NHS, 2022).

Overall, autistic people make fewer journeys than allistic people (Mackett, 2017). Ableism can lead to lack of confidence, concerns about ableist attitudes from both passengers and staff and anxiety (Mackett, 2017). Ableism from carers and the labelling of autistic people as “vulnerable” can cause mollycoddling and limit their freedom to make journeys independently (Mackett, 2017). On all journeys, autistic people can face sensory ‘issues’ such as loud music and chatter (Song, et al., 2023; Mackett, 2017). All transport can also be restricted by its cost (Mackett, 2017). These difficulties apply to all forms of transport; some specific forms of transport will be addressed in the headings below.

Public Transport Such as Bus and Train

All neurodivergent people, including autistic people use buses and trains less than non-disabled people and often not at all (Mackett, 2017). Taking a bus or train, including to work, for autistic people requires them to talk to a bus driver or train conductor, such as in the case of paying the fare but drivers and other staff can often be ableist, “rude and unhelpful” (Mackett, 2017, p. 25). Autistic people also need to know the ‘social rules’ of the bus such as where it is acceptable to sit, which many autistic people do not pick up naturally compared to allistic people (NHS, 2022; Mackett, 2017). Bus and trains often do not come on time and autistic people can find this stressful (NHS, 2022; Mackett, 2017). The most cited reason for autistic people using a bus less than they desired was anxiety/lack of confidence (21%), followed by cost (15%), over-crowding (8%), delays and disruption (7%) and fear of crime (6%) (Mackett, 2017). Reasons for the train were similar anxiety/lack of confidence (17%), cost (14%), over-crowding (7%), transport unavailable (6%) and difficulty getting to the station (6%) (Mackett, 2017).

While 72% of non-disabled people were satisfied with the Bus Driver’s helpfulness and attitude, only 61% of autistic people were satisfied (Mackett, 2017). Likewise, 73% of non-disabled people were satisfied with their greeting and welcome but only 61% of autistic people were satisfied (Mackett, 2017). Over double the number of autistic people (14%) found the behaviour of other passengers a concern compared to non-disabled people (6%) (Mackett, 2017). Bus and railway staff are perceived as more friendly and helpful towards physically disabled people than neurodivergent people (Mackett, 2017).

Driving

There is a lack of research into the driving ability of autistic people, however it is likely that they find it difficult due to processing many things simultaneously (Mackett, 2017; Song, et al., 2023; Gowen, et al., 2024).

Taxis and Car Sharing

Taxis and car sharing offer advantages for autistic people over other forms of transport to work. Taxis can take people door to door and can provide assistant (Mackett, 2017). The passenger only needs to interact with the driver and has the option to not communicate with them directly if they prefer (Mackett, 2017). In fact, the option of a taxi to and from school is given to pupils with special educational needs in Northern Ireland, including autistic people but only if “it is necessary to meet the specific needs of a pupil, or there is no other feasible alternative” (Education Authority, 2024).

Solutions

The NDS mentions an Access to Work scheme which will cover the costs for disabled people who cannot take public transport, which is beneficial for autistic people because of the difficulties they often have with other forms of transport (Disability Unit, et al., 2021). Especially as taxi and car sharing seems to be the mode of transport, they have the least difficulty with (Mackett, 2017). However greater change is needed, especially during the time of a climate emergency, as public transport is better for both the environment and traffic congestion (Allen, et al., 2018; Taylor, 2021). An example of change that can enable more autistic people to use public transport more frequently is staff training, which has positive outcome in the European Union (Mackett, 2017). The inclusion of autistic children in mainstream education helps non-disabled people have less ableist attitudes when they become adults (Mackett, 2017). Mobile apps, such as Google Maps, have helped autistic people with wayfinding and planning journeys (Mackett, 2017).

Mental health support

The NDS does not state what it will do to provide mental health support for disabled people, just that it will (Disability Unit, et al., 2021). Whether one believes that autistic people are more likely to experience mental health issues because of autism itself (like the medical model would suggest) or societal attitudes towards Autistic people (like the social model would suggest); it is undeniable that they are more subjective to them (Mitchell, et al., 2021). Mainstream mental health support is often ineffective for autistic people, a meta-study finding that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has a small-to-medium size effect (Weston, et al., 2016). The reason for CBT being ineffective in autistic patients remains unknown. However, some anecdotal evidence suggests that it is because it is about challenging one’s thoughts and autistic people have had their thoughts doubted since they could talk (Stimpunks, n.d). Many autistic people tend to overanalyse their thoughts and feelings and have been “browbeaten to ignore their emotions” (Price, 2022, p. 74). Therefore, the policy could provide alternatives to CBT such as Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Ableism and Lack of Knowledge

Knowledge and understanding about autism are lacking in the UK. A YouGov poll found that the public still believe common myths and misconceptions about autism; 35% believe it is the same as a learning disability, 30% are unsure if autism can be ‘cured’ and 39% believe autistic people lack empathy (Autistica, 2022). This has the potential to translate into not hiring autistic people and not providing the right support for autistic employees.

A study by the NAS (2016) found that 48% of autistic employees have been bullied or harassed at work and 51% reported ableism. This is likely to be underreported as autistic people are often unaware that they are, being or have been bullied (NAS, n.d). An individual bullied at work faces consequences for themselves; having increased rates of anxiety, depression, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) burnout and emotional exhaustion. Bullying also has consequences for the organisation, with increased absences and lower productivity (Hershcovis, et al., 2015).

40% of employers believe that it is more expensive to employ an autistic person. This is despite adjustments being cheap and quick “through spreading understanding or simple adaptations to the environment” (NAS, 2016). However, the NAS (2016) does not document the reasons they believe this. In order to rerectify this, the NDS could teach, train or inform employers about common misconceptions about disabilities but it does not state it will do this (Disability Unit, et al., 2021).

Reasonable Adjustments

Disabled employees have the right to request ‘reasonable adjustments’ under the Disability Discrimination Act in Northern Ireland, and the Equality Act in the rest of the UK. Examples of ‘reasonable adjustments’ are adjusting the lighting or alternating the way one speaks (Davies, et al., 2022). However, under the aforementioned laws what is considered ‘reasonable’ is determined by the employer, not the disabled person. Furthermore, disabled people are expected to disclose their disability and provide evidence that they are beneficial and not trivial (Davies, et al., 2022). Undiagnosed autistic people, who may be on a long waiting list to receive their diagnosis (Department of Health, 2024), are not able to ask for ‘reasonable adjustments’ at all due to the law being based on the medical model (Oliver, 1990; Slorach, 2016).

Autistic employees who do ask for adjustments are labelled ‘troublesome’ or ‘unreasonable’ with employers not believing they had any need for them (Davies, et al., 2022). Yet there is evidence that physically disabled employees do not receive the same amount of stigma (Davies, et al., 2022). The outcome of lack of adjustments led to poor mental health (8.3% of respondents), changes to employment status (5.8%) or unfair dismissal (3.3%) (Davies, et al., 2022).

The policy will introduce the ‘Access to Work scheme’ that “provides support for disabled people at work that is not covered by employers’ responsibility to make reasonable adjustments” (Disability Unit, et al., 2021). This does not acknowledge that the current system is failing autistic employees.

The NDS (Disability Unit, et al., 2021) also will create an advice hub for disabled people (ex NI) which will provide advice to disabled people about ableism, their rights and ‘reasonable adjustments’. This could improve the confidence of autistic people to ask for adjustments but will not do a lot to make more employers accept them.

Conclusion

Since the 2008 financial crisis, disability policies have been inadequate, including measures on employment, and while the NDS appears to be based on the social model, it is no different. Autistic people continue to have higher levels of unemployment and a wider pay gap, even compared to other marginalised groups which was examined in the section Understanding the Policy Issues, figures 1 and 2.

The NDS does address ways for autistic employees to cope with meltdowns and shutdowns by allowing them to work from home or in a different location. It does say that it will give mental health support, but not what it is, or if it is suitable for autistic people. It does little to address their unemployment levels, just guaranteeing job interviews, a situation where autistic people experience high levels of ableism. Nor does it do anything to address the levels of bullying and ableism in the workplace or improve or change attitudes. It does not acknowledge the lack of acceptance of reasonable adjustments requested by autistic people but will provide an advice hub which could give them more confidence to ask for them in the first place.

Reference List

Allen, M., Babiker, M., Chen, Y., de Coninck, H., Connors, S., van Diemen, R., Dube, O.P., Ebi, K.L., Engelbrecht, F., Ferrat, M., Ford, J., Forster, P., Fuss., S., Guillen, T.B., Harold, J., Hoegh-Guldberg, Hourcade, J.C., Huppmann, D., Jacob, D., Jiang, K., Johansen, T.G., Kainuma, M., de Kleijine, K., Klejine, E., Ley, D., Liverman, D., Mahowald, N., Masson-Delmotte, V., Matthews Robin, J.B., Millar, R.j., Mintenbeck, K., Morelli, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Mundaca, L., Nicolai, M., Okereke, C., Pathak, M., Payne, A., Pidcock, R., Pirani, A., Poloczanska, E., Portner, H.O., Revi, A., Riahi, K., Roberts, D.C., Rogelj, J., Roy, J., Seneviratne, S.I., Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Shindell, D., Singh, C., Solecki, W., Steg, L., Taylor, M., Tschakert, P., Waisman, H., Warren, R., Zhai, P., Zickfeld, K . (2018) Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5c, s.l.: IPCC.

Autistica (2022) Awareness isn’t enough: understanding is critical to acceptance. Available at: https://www.autistica.org.uk/news/attitudes-index-news

[Accessed 25 March 2024].

Baker, C., Hawkins, O., Audickas, L., Bate, A., Cracknell, R., Apostolova, V., Dempsey, N., McInnes, R., Rutherford, T., Uberoi, E. (2019) General Election 2017: full results and analysis. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7979/ [Accessed 29 March 2024].

Bellanca, N. (2013) Capitalism. Handbook on the economics of reciprocity and social enterprise, pp. 59-67.

Carpenter, S. (2020) Laughing at Natural Fools. In: J. McGavin & G. Walker, eds. Early Performances: Courts and Audiences – Shifting Paradigms in the Early English Drama Studies. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 197-210.

Davies, J., Heasman, B., Livesey, A., Walker, A., Pellicano, E., Remington, A. (2022) Autistic adults’ views and experiences of requesting and receiving workplace adjustments in the UK. Plos One, 17(8).

DeBrabander, K.M., Morrison, K.E., Jones, D.R., Faso, D.J., Chmielewski, M., Sasson, N.J. (2019) Do First Impressions of Autistic Adults Differ Between Autistic and Nonautistic Observers? Autism in Adulthood, 1(4), pp. 250-257.

Disability Unit, Equality Hub., Department for Work and Pensions, Tomlinson., J., Coffey, T. (2021) National Disability Strategy. London: Gov.uk.

DPAC. (2011) About. Available at: https://dpac.uk.net/about/ [Accessed 28 March 2014].

Evans, E. (2023) Disability policy and UK political parties: absent, presents or absent-present citizens? Disability & Society, 38(10), pp. 1743-1762.

Finn, M., Flower, R., Leong, H. & Hedley, D. (2023) ‘If I’m just me, I doubt I’d get the job’: A qualitative exploration of autistic people’s experiences in job interviews. Autism, 27(7), pp. 2086-2097.

Gowen, E., Earley, L., Waheed, A. & Poliakoff, E. (2024) From “one big clumsy mess” to “a fundamental part of my character.” Autistic adults’ experiences of motor coordination. PLoS One, 18(6).

Grella, O.N, Dunlap, A., Nicholson, A.M., Stevens, K., Pittman, B., Cobera, S., Diefenbach, G., Pearlson, G. & Pearlson, G., (2022) Personality as a mediator of autistic traits and internalizing symptoms in two community samples. BMC Psychology, 10(1).

Hershcovis, M., Reich, T. & Niven, K. (2015) Workplace bullying: Causes, consequences and intervention strategies. SIOP: White Paper Series, pp. 1-22.

Jones, D.R., Botha, M., Ackerman, R.A., King, K. & Sasson, N.J., (2023) Non-autistic observers both detect and demonstrate the double empathy problem when evaluating interactions between autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism, 0(00), pp. 1-13.

Kemp, K. & Schweitzer, B. (2024) Liberating the Colonized Body and Mind: A Theology of Race and Disability. International Review of Mission, 113(1), pp. 6-22.

Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust, n.d. Meltdowns and Shutdowns. Available at: https://www.leicspart.nhs.uk/autism-space/health-and-lifestyle/meltdowns-and-shutdowns/ [Accessed 24 March 2024].

Mackett, R. (2017) Building Confidence – Improving travel for people with mental impairments, London: Centre for Transport Studies.

Mitchell, P., Sheppard, E. & Cassidy, S. (2021) Autism and the double empathy problem: Implications for development and mental health. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 1(39), pp. 1-18.

NAS. (2016) “I’m not unemployable I’m autistic”: The autism employment gap – too much information. Available at: https://s3.chorus-mk.thirdlight.com/file/1573224908/63516243370/width=-1/height=-1/format=-/fit=scale/t=444848/e=never/k=59f99727/TMI%20Employment%20Report%2024pp%20WEB.pdf

[Accessed 26 March 2024].

NAS (2021) New shocking data highlights the autism employment gap. Available at: https://www.autism.org.uk/what-we-do/news/new-data-on-the-autism-employment-gap

[Accessed 18 March 2024].

NAS (n.d.) Dealing with bullying – a guide for parents and carers.

Available at: https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/bullying/bullying/parents

[Accessed 25 March 2024].

NHS. (2022) Signs of autism in adults. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism/signs/adults/

[Accessed 22 Oct 2024].

Oliver, M. (1990) The Politics of Disablement. 1st ed. London: Red Globe Press.

O’Nions, E., Petersen, I., Buckman, J.E., Charlton, R., Cooper, C., Corbett, A., Happe, F., Manthorpe, J., Richards, M., Saunders, R. & Zanker, C. (2023) Autism in England: assessing underdiagnosis in a population-based cohort study of prospectively collected primary care data. THE LANCET Regional Health, Volume 29.

ONS (2021a) Outcomes for disabled people in the UK: 2021. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/outcomesfordisabledpeopleintheuk/2021#employment

[Accessed 18 March 2024].

ONS (2021b) Disability Pay Gap in the UK: 2021.

Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/disabilitypaygapsintheuk/2021#disability-pay-gaps-data

[Accessed 18 March 2024].

ONS. (2023a) Ethnicity pay gaps, UK: 2012 to 2022.

Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/ethnicitypaygapsingreatbritain/2012to2022#:~:text=The%20Mixed%20or%20Multiple%20ethnic,ethnic%20employees%20in%20Figure%201.

[Accessed 19 March 2024].

ONS (2023b) Gender pay gap in the UK 2023.

Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2023

[Accessed 18 March 2024].

Pearson, A. & Rose, K. (2021) A conceptual analysis of autistic masking: Understanding the narrative of stigma and the illusion of choice. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), pp. 52-60.

Price, A. (2022) Who Are the Masked Autistics?. In: M. Eniclerio, ed. Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity. New York: Harmony Books, p. 74.

Russel, G., Stapley, S., Newlove-Delgado, T., Salmon, A., White, R., Warren, F., Pearson, A. & Ford, T. (2022) Time trends in autism diagnosis over 20 years: A UK population-based cohort study. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(6), pp. 674-682.

Sasson, N.J., Faso, D.J., Nugent, J., Lovell, S., Kennedy, D.P. & Grossman, R.B. (2017) Neurotypical Peers are Less Willing to Interact with Those with Autism based on Thin Slice Judgments. Scientific Reports, 7(1), pp. 10-10.

Slorach, R. (2016) A Very Capitalist Condition: A History and Politics of Disability. 1 ed. London: Bookmarks.

Song, W., Salzer, M., Pfeiffer, B. & Shea, L. (2023) Transportation and Community Participation Among Autistic Adults. Inclusion, 11(1), pp. 40-45.

Stimpunks (n.d) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

Available at: https://stimpunks.org/glossary/cognitive-behavioral-therapy/#h-cbt-and-autism

[Accessed 26 March 2024].

Taylor, L. (2021) Want to create 5 million green jobs? Invest in public transport in cities.

Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/04/here-s-why-cities-should-invest-in-public-transport/

[Accessed 10 Nov 2024].

UNISON (2013) 5: Welfare reform changes affecting disabled people. Available at: https://www.unison.org.uk/content/uploads/2013/07/On-line-Catalogue217093.pdf

[Accessed 28 March 2024].

United Nations – Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Social Inclusion (n.d.) Article 27 – Work and Employment.

Available at: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/article-27-work-and-employment [Accessed 11 April 2024].

Wegscheider, A. & Guevel, M. (2021) Employment and disability: Policy and employers preceptive in Europe. European Journal of Disability Research, 15(1), pp. 2-7.

Weston, L., Hodgekins, J. & Langdon, P. (2016) Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy with people who have autistic spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 1(49), pp. 41-54.