Fit for purpose’ or even ‘fit to be heard’? – A critical review of the Northern Ireland curriculum for Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) for deaf female students in secondary mainstream education By Lisa McGuigan

MEd PGT Educational studies

Introduction

Once again, attention has been piqued over Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) in Northern Ireland (NI), with the launch of an inquiry by The Assembly Committee for Education into its teaching and implementation in schools (NI Assembly, 2024).

Under the Education (Northern Ireland) Order 2006, the revised Northern Ireland Curriculum was introduced in all grant-aided schools, funded directly by the Department of Education and managed by Boards of Governors – representatives from various stakeholders including parents, teachers, the Education Authority and, often, the Roman Catholic or Protestant church. In line with the revised curriculum, Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) became a statutory requirement of personal development for post-primary schools. However, debate has arisen around the efficacy, inclusivity and legal cognizance of current RSE teaching amidst recommendations to address the prevalence of sexual crime against women and girls outlined in the Gillen Report (2019) and evolving legal frameworks around reproductive rights and abortion (NI Assembly, 2024). Considering such shifts in the landscape of sexual and reproductive rights, the Assembly Committee’s assessment of RSE provision in providing such essential health education that aligns with our children and young people’s diverse needs is a very welcome, and necessary one.

The Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (CCEA) stated the purpose of RSE policy is to promote holistic development of the child, designed to “…empower young people to achieve their full potential and to make informed decisions throughout their lives.” (CCEA, 2015, p 4.). Following the last published evaluation of post-primary RSE published by The Education and Training Inspectorate [ETI] in 2011, calls were made for post-primary schools to review their policies, procedures and practices in RSE to ensure this purpose was fully realised.

The report, ‘An Evaluation of Relationships and Sexuality Education in Post-Primary Schools’ (ETI, 2011), highlighted the need to address clear gaps in provision and more robust evaluation of existing provision and the requirement for the more professional development a priority. Consequently, CCEA was commissioned by the Department of Education for Northern Ireland (DENI) in providing schools with specific guidance to address shortfalls in the fitness for purpose of RSE. This was issued along with a collection of resources to ensure access of all children to an RSE curriculum that was relevant, high quality, inclusive, and that upheld the principles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [CRC] (1989). However, it was simply that: guidance. has aided in the persistence of systematic inconsistencies and unequal access of our children and young people to RSE education (Meredith, 2022). In this paper I will explore the ‘fitness for purpose’ of current RSE policy in Northern Ireland for students in mainstream post-primary education, including the content, construction and implementation. I will also discuss the subsequent effects of the policy on students, particularly those who are female and deaf.

Basic, biased and building barriers

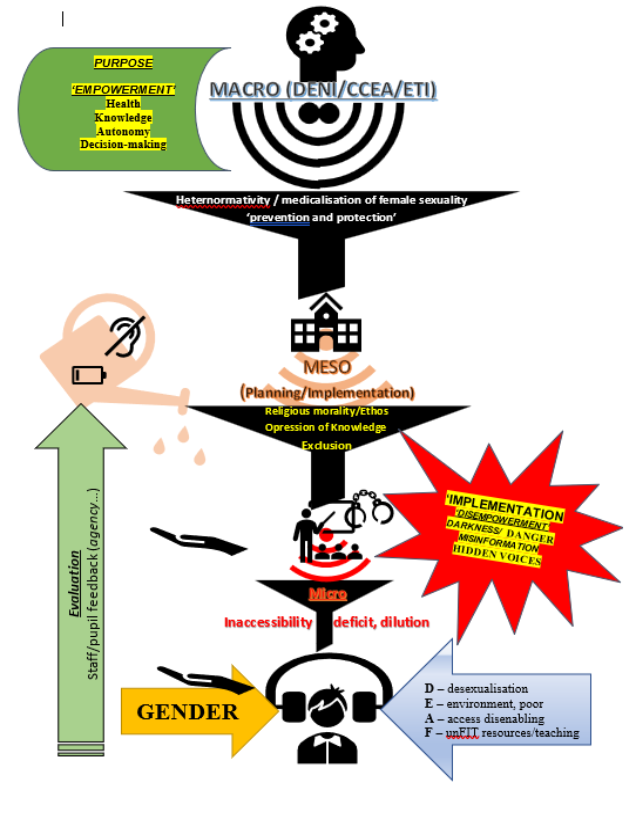

The key aims of the Northern Ireland Curriculum are to promote young people in their personal growth and potential, developing each child as a whole (ETI, 2011). Central to this is empowering pupils through RSE to make informed decisions about relationships, sexual identity and intimacy throughout their lives (CCEA, 2015). By providing them with knowledge on sexual and reproductive health rights which is “up-to-date, accurate and accessible” (CCEA, 2015; p5), this objective can be achieved. Albeit framed by DENI and CCEA as a statutory requirement at a macro level, RSE policy varies in its planning and implementation at a meso level (see Fig. 1). The tone and the content of the RSE curriculum is often decided by school stakeholders who are given the freedom to tailor it to the ethos of the school (Miller, 2021), perhaps also passing through a further and finer filter of teacher agency at a micro level.

In the education system of Northern Ireland, uniquely shaped as it is by the segregation of students on the basis of ability, sex or religious belief (Wilkinson, 2017), this poses problematic inconsistency of policy founded on non-prescriptive content that can be aligned with the values, morals or religious ethos of the school, stakeholders or individual teachers (DENI, 2013). The school system in Northern Ireland includes various types of schools; primarily divided into controlled and maintained sectors, there is also a significant focus on integrated schools. The controlled schools are managed by local Education Authorities, while maintained schools, typically religious and more than often Roman Catholic, are managed by their own respective Boards of Governors. Integrated schools, a growing sector, aim to bring together children from different backgrounds and faiths.

As illustrated in figure 1, misalignments thus arise between RSE policy aims and its implementation in the classroom, resulting in partial knowledge of relationships, sexual identity and intimacy among students (or a complete lack thereof). Furthermore, negotiation and delivery of micro policy can impose barriers for children with additional needs. Weak, poor or non-existent RSE provision leaves students at best with the most basic, minimum content of the RSE curriculum or, worse, with none at all. Thus, making them vulnerable to risk, exploitation and even abuse (CCEA, 2015) as they do not develop the knowledge or skills to have safe, The tensions between a policy, which may already be steeped in dominant narratives of religion, heteronormativity and gender inequality (Wilkinson, 2021), and its implementation have created a burgeoning chasm between the RSE young people and the RSE they may or may not receive.

Figure 1: Curriculum Map of the Northern Ireland Relationships and Sex Education Policy for Post Primary Schools (2015)

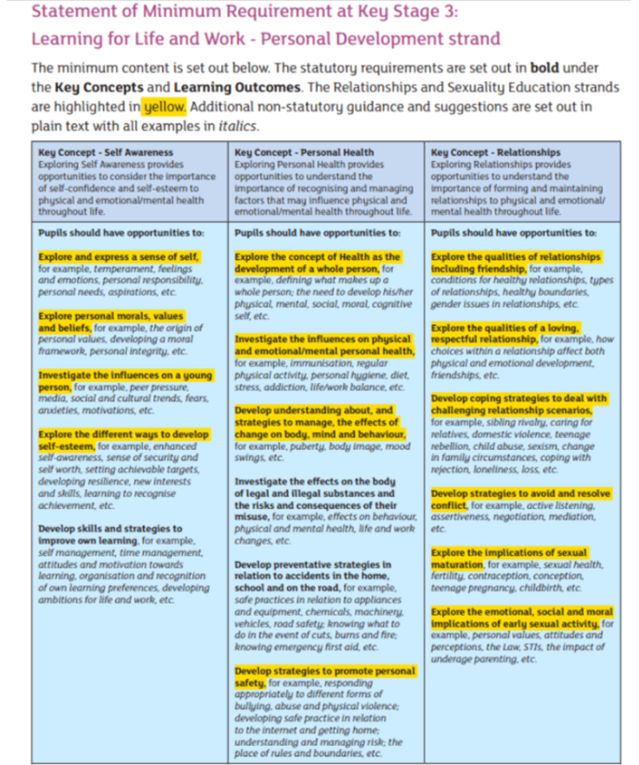

An overarching misalignment in RSE provision with its purpose might originate at the macro level, in policy that is incongruent with the experiences of young people today, contradicting the aim to value all gender and sexual identities relating to the Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations (Equality Commission NI, 2006) and perpetuating hegemonic heteronormative knowledge. One might argue that declared key concepts and objectives in the KS3 Personal Development strand of Learning for Life & Work (CCEA, 2015) reproduces tacit dominant narratives rooted in conservative, even archaic, conventions that perpetuate inequality rather than inclusion around gender identity and, particularly, female sexuality. For example, as seen in figure 2; references made in the policy document towards providing opportunities to explore a students’ holistic health to “develop his/her physical, mental, social, moral, cognitive self” (CCEA, 2015, p. 37) exclude gender identities beyond the rigid binary of “being male or female” (CCEA, 2015, p.5) and diverse sexual orientations.

Wilkinson (2021) argues this omission of rich and varied gender and sexual identities marginalises entire communities through promoting, what students themselves call, a ‘basic’ and ‘biased’ policy (Roberts et al., 2019) that excludes any reference to the non-binary or transgender experience. These dominant, dangerously exclusionary narratives that pervade RSE education transcend the Northern Irish context, existing on a global scale and impacting students of every ability and need. In Sweden, Nelson and Odberg Pettersson (2019) also found a norm of heteronormativity in RSE impacts students with disabilities, for instance, in teachers assuming that their students were heterosexual or desexualised completely in their own right. This indicates how the policy itself misaligns with its purpose of empowering students, possibly leading to trivialisation of student experiences and disempowerment within RSE, even symbolic annihilation (Tuchman, 2000). The pervasive absence of representation of diverse and inherent sexual identities is to deny their existence. Furthermore, as depicted in figure 1; coupled with the dilution of RSE content statements through various filters of morality, school ethos and teacher implementation, whole communities of students are not only invisible but also silenced and left in the dark when it comes to recognising safe and healthy sexual relationships.

Figure 2: Statement of Minimum Requirement at Key Stage 3: Learning for Life and Work – Personal Development strand. CCEA, 2015

Issues surrounding curriculum construction

When considering curriculum construction in this context, the declared minimum content and objectives may also be understood using the ‘behaviouristic’ approaches of curriculum design outlined by the seminal analogies of Bobbit (1918) and Bloom et al. (1956). These academics see curriculum as ‘product’ and based on pre-determined content and clear objectives, the completion of such a design driven by creating the finished product of an individual prepared for their future adult role (Bobbit, 1918).

The RSE curriculum could also be seen as product-oriented, the fulfilment of a number of objectives which culminate in a ‘pupil product’ competent to “make informed, responsible decisions about their relationships and sexual health” (CCEA, 2015 p3) about “sexual maturation” and the “implications of early sexual activity” such as regarding fertility, contraception, teenage pregnancy, childbirth etc (CCEA, 2015 p37). These remits of sex and bodily autonomy are tied to a discourse of medicalisation and repression of female sexuality, that is reduced to reproductive contexts and contraceptive control, put crudely sexual problematisation rather than sexual pleasure. This hidden curriculum controls young women in particular. For instance, educators in Northern Ireland have been found to commonly discourage contraceptive awareness or provide partial perspectives, antid-abortion stances and abstinence rooted in Christian moral conservatism (Roberts et al, 2021). Selectivity of RSE content and perspectives ultimately creates a deficit in knowledge of healthy, sex positive relationships and pleasure for females, meaning they may lack the tools to make decisions, recognise and challenge unhealthy relationships or protect themselves. This not only questions the policy’s fitness for purpose, but increases females’ vulnerability to sexual exploitation (Marshall, 2014) contradicting Article 34 of the UNCRC (1989, n.p.) under which governments are duty-bound to “protect children from all forms of sexual abuse and exploitation”. According to research, one in three adolescent girls and 16 per cent of boys have experienced sexual violence (Barter et al., 2009), the increased vulnerability of females clearly noting the knowledge and skills they are lacking from inadequate education. Repressive conceptualisations of sexuality are not exclusive to Northern Ireland but are also identified by Michielson and Brockenschmidt (2021) as barriers to sexuality education for children and young people with disabilities throughout Europe. Though awareness is increasing around the parity of disabled students of their RSE needs to their peers without disabilities, the focus on RSE programmes continues to base the curriculum on protection and prevention rather than on positive sexual identity (Michielson and Brockenschmidt, 2021). This is a common theme of misalignment with RSE’s aim of empowerment.

Framing within the RSE curriculum; sex-positive or sex-palatable?

The statutory guidance provided by CCEA has directed that RSE policy should be tailored to the values, morals and ethos of the school, and be reflective of “the principles held by parents and school management authorities” (DENI, 2013 p.2). A report from the ETI indicated that 93% of schools have policies tailored to their values and ethos (ETI, 2011), creating incredible variance in RSE policy and practice across most schools. Framing, as discussed by Bernstein (1975, p80), refers to the “degree of control teachers and pupils possess over the selection, organisation, pacing and timing of the knowledge transmitted and received in the pedagogical relationship”. The lack of prescriptive requirements or restrictions as to what knowledge is conveyed and how, is indicative of what Bernstein (1971) termed weak framing within curriculum. This allows key stakeholders in schools, again adults, to exert their agency in reproducing knowledge at a meso-level of curriculum development, facilitating selectivity of content “endorsed by a school’s Board of Governors” (DENI, 2013, p3) and leading to an inconsistent provision of RSE.

In the context of Northern Irish education, the underpinning religious influence on RSE policy and design is still evident and authoritative as evidenced by the numerous sources it cites. For example, the selection of school provision based on Christian moral conservatism outlined above (Roberts etc al, 2021). There is also evidence of a dangerous ‘trade-in’ of purpose in the implementation of RSE to make it more ‘palatable’ with the ethos of the school or parents, if it is implemented at all. For instance, Roberts et al. (2021) found that students said that they rarely received RSE and 60 % regarded the content of limited use, if at all. Lafferty et al. (2012) also found in their study of Northern Ireland that conservative religious beliefs significantly influenced what was considered acceptable sexual behaviour for young people with disabilities.

The lack of uniformity and weak framing is even more concerning when considered in the context of young people with special educational needs (SEN) in mainstream education. Schools must have appropriate, accessible and relevant RSE for SEN students, to ensure that barriers to participation are removed. However, weak framing defers control to teachers on how policy is implemented in classrooms (Bernstein, 1971). The provision needed to meet the communication needs of, for example, deaf pupils is often not delivered in a micro-curriculum efficiently, meaning they cannot access an already limited curriculum. The majority (78%) of deaf children in Northern Ireland attend mainstream schools (CRIDE 2019). Considering the implementation of RSE in this instance, the mode of delivery is crucial as, according to the charity Deafex, traditional teaching methods rooted in oral delivery are putting deaf pupils at risk during RSE provision (cited in Swinbourne, 2012).

These students are liable to miss up to 50% of everyday language (NDCS, 2021) due to communication and language barriers, poor acoustic environments and a lack of deaf-friendly resources (Swinbourne, 2012). Teachers throughout Ireland still rely heavily on oral methods of delivery and assessment, based in the erroneous assumptions that student’s hearing is ‘fixed’ with a hearing aid or cochlear implant (Archbold et. al., 2015; Miller, 2022). A report on the Irish RSE curriculum found that the most frequently used technique by teachers was in-class oral questioning and discussion, which was used 98% of the time (DEN, 2013). For deaf students, who may appear to engage well when acoustics allow (Archbold et. al., 2015), or who have good lipreading skills lulling teachers into thinking they have understood more than they have (Johnson, 2004), this can result in knowledge gaps that leave them more even vulnerable than their hearing peers to sexual exploitation, abuse and risk behaviours (Berry, 2017). For example, research by Kvam (2004) suggests risk factors of gender and disability intersect to increase the vulnerability of deaf girls to victimisation and are more likely than their hearing peers to experience sexual assault. This is denoted in figure 1.

Agents of change

There is a case for the teacher agency as a vehicle for inclusion; a more positive negotiation of the RSE curriculum as a process in accommodating any and every learner (Bruner, 1960) might address why RSE policy is not fit for purpose. Priestly et al. (2015) described the classroom teacher as an agent of change and transformation; such change is possible when considering Bernstein’s (1975) previously discussed concept of framing – who possesses control and agency over what knowledge is transmitted and how. The weak framing of the RSE policy arguably places control in the hands of the transmitter, potentially providing the space for teacher agency to tailor RSE policy implementation for deaf pupils in the mainstream classroom, and many successfully do. In fact, some believe this presents an opportunity for dynamic shared control between teachers and learners (Macdonald and Jóhannsdóttir, 2006) of what knowledge is transmitted in the classroom and how. Yet, the teacher does not operate in a vacuum and neither do the structures that circumscribe their agency. Mechanisms and obstacles such as ethos, management structures, lack of resources/equipment as well as limited expertise/training, can lead to engagement with policy that is fraught with unintended consequences (Priestly et al. 2015). With the best intentions, agency will be overcome and limited by surrounding structures, which could also be said of schools’ agency in general. The ETI (2015) uncovered an urgent need for more guidance in teacher training, trained professional support and whole-school development in RSE, meaning many teachers are not equipped to provide adequate implementation of a fit for purpose policy. This was echoed by Suter (2009) who found RSE policy must be supported by training and trained professionals to overcome current challenges educators face in implementing inclusive policy for the benefit of all, but especially for deaf children’s development into confident, responsible and well-informed young adults.

While not named stakeholders at institutional/governmental level, statutory guidance clearly states that schools should seek the feedback of students to provide actionable feedback to better meet their needs (CCEA, 2015). Here children’s voices are acknowledged in RSE policy development, though they are diffused within the structural and cultural factors discussed. Any data gathered from students via internal process could suggest improvement; however, any findings will be reported directly to Governors who ultimately have power of policy to exert action, or not. The monitoring and evaluation of curriculum also hinges on whatever ‘palatable’ helping of the RSE curriculum children are served by adults assuming that they have not been withdrawn by parents, who are afforded the choice to remove them (CCEA, 2015). Despite the cries for proactive and collaborative RSE (Roberts et al., 2021), children’s voices remain muted by adults who have a monopoly experience as holder of rights and an actor of self-interest. In line with a conflict perspective, knowledge is weaponised to transmit and legitimise power of adults over children (Bourdieu 1973), in turn preventing children themselves from becoming advocates of their right to voice their rights, to act on them and exact radical change.

Conclusion

Current RSE in Northern Ireland is NOT fit for purpose, in particular, for deaf females in mainstream education. The misalignment with purpose, legitimations of oppressive knowledge systems, language barriers and lack of informed pedagogy highlight a treacherous effect on children, particularly when gender and deafness interact (- illustrated in Figure 2). With a lack of research on the deaf female students’ experience of current RSE provision, there is an opportunity to prioritise their voices using a rights-based approach to explore how gender and disability interact in experiences of RSE in Northern Ireland. In exploratory research, I would use interviews to ascertain deaf female students’ experience (or lack thereof) that could give educators insight into how to best help deaf students access knowledge and tools to protect themselves and enjoy safe and satisfying relationships. Though child-centred reform is needed on all levels of policy, this may align micro-level curriculum with a truly inclusive, proactive and positive purpose.

Addendum

Since this article was written, the Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) curriculum in Northern Ireland has undergone a series of revisions reflecting broader societal shifts and reforms mandated by national and international legislative changes. In 2023, the Relationships and Sexuality Education (Northern Ireland) (Amendment) Regulations 2023 amended the Education (Northern Ireland) Order 2006 and the Education (Curriculum Minimum Content) Order (Northern Ireland) 2007 (DENI, 2023); this actioned the inclusion of “comprehensive, inclusive, and scientifically accurate” RSE content on “sexual and reproductive health and rights, covering prevention of early pregnancy and access to abortion” at Key Stages 3 and 4 (DENI, 2024, p.2). These changes were implemented in response to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 2019) recommendation 86(d), which called for improved access to information on sexual and reproductive health and rights. As a result, schools are now required to provide instruction on topics such as consent, contraception, abortion, and LGBTQ+ inclusion, with opt-out provisions for parents in specific areas.

Whilst schools are required to deliver a more inclusive and expanded statutory minimum content; the curriculum still affords a large degree of flexibility in how their RSE taught programme is developed and delivered (DENI, 2024). Evaluations by the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI, 2023) still reveal inconsistencies in RSE delivery, and most recently, the 2025 Strategic Review of the Northern Ireland Curriculum (Crehan, 2025) highlighted that even the most recent configuration RSE curriculum had not kept pace with international best practices. In sum, the author acknowledges that there have been concerted efforts in recent years to modernise and standardise the delivery of RSE across educational settings in Northern Ireland, the issues highlighted in this article persist. Particularly in the context of the intersectionality of gender and disability, the need for enhanced teacher training and the urgency of actioning the recommendations of students themselves, as advocates in their own right.

Reference List

Archbold,S; Ng, Z.Yen; Harrigan, S; Gregory, S; Wakefield, T; Holland, L; Mulla, I. Experiences of young people with mild to moderate hearing loss: Views of parents and teachers. Ear Foundation report to the National Deaf Children Society, May 2015.

Barter, C; McCarry, M; Berridge, D and Evans, K, (2009) Partner Exploitation and Violence in Teenage Intimate Relationships, National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC).

Bernstein, B. (1971) On classification and framing of educational knowledge. London: Macmillan.

Bernstein, B. (1975). Class, Codes and Control: Towards a Theory of Educational Transmissions. (Vol. 3). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Berry, M. (2017). Being deaf in mainstream education in the United Kingdom: Some implications for their health. Universal Journal of Psychology, 5(3), pp. 129–139.

Bloom, B., Englehart, M. Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York, Toronto: Longmans, Green.

Bobbitt F. (1918) The Curriculum, Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Bourdieu, P. (1973, 1st Edition) Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction, Knowledge, Education, and Cultural Change, Imprint: Routledge

Bruner (1960) The Process of Education, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Consortium for Research into Deaf Education (CRIDE) (2019) CRIDE report on 2018/2019 survey on educational provision for deaf children.

Council for the Curriculum, Examinations & Assessments (CCEA) (2015) Relationships and

Sexuality Education Guidance an Update for Post-Primary Schools, pp 1-53.

Crehan, L (2025) ‘A Strategic review of the Northern Ireland Curriculum; A Foundation for the Future: Developing Capabilities Through a Knowledge-Rich Curriculum in Northern Ireland’ Department of Education Northern Ireland.

Department of Education and Skills (DEN): (2013) Looking at Social, Personal and Health Education: Teaching & Learning in Post-Primary Schools, pp. 1-42.

Department of Education for Northern Ireland (DENI): (2013) Circular 2013/16 – Relationships and sexuality education policy. Available at (Circular 2013/16 – Relationships and sexuality education policy | Department of Education, 2015)

Department of Education for Northern Ireland (DENI): (2015) Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE) guidance. (pp 1 -8); Available at (Circular 2013/16 – Relationships and sexuality education policy | Department of Education, 2015).

Department of Education Northern Ireland (DENI). (2023). Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE). [Online] https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/articles/relationship-and-sexuality-education-rse.

Department of Education Northern Ireland (DENI). (2024) ‘Circular 2024/01 – guidance on amendments to the relationship and sexuality education (2023)

The Education & Training Inspectorate (2011); Report of an Evaluation of Relationships and Sexuality Relationships Education in Post-Primary Schools. (pp 1-29)

The Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI) (2023) ‘The Preventative Curriculum in Schools and Education Other Than at School (EOTAS) Centres’ Education and Training Inspectorate – Empowering Improvement.

Equality Commission for Northern Ireland (2006) Sexual Orientation Discrimination Law in Northern Ireland – A Short Guide

Johnson, J. (2004) ‘Parents and their deaf children: The early years. Kathryn P Meadow-Orlans, Donna M Mertens, Marilyn A Sass-Lehrer’, Deafness and Education International, 1 January, pp. 127–128.

Kvam, M. H. (2004). Sexual abuse of deaf children. A retrospective analysis of the prevalence and characteristics of childhood sexual abuse among deaf adults in Norway. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(3), pp. 241-251.

Lafferty, A., McConkey, R., & Simpson, A. (2012). Reducing the barriers to relationships and sexuality education for persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 16(1), 29–43.

Macdonald, A., and Jóhannsdóttir, T. (2006). “Fractured pedagogic discourse: teachers’ responses to educational interventions,” Paper presented at the European Conference on Educational Research, September 2006, Geneva.

Marshall, K., (2014) Child Sexual Exploitation in Northern Ireland Report of the Independent Inquiry

Michielsen, K. and Brockschmidt, L. (2021) ‘Barriers to sexuality education for children and young people with disabilities in the WHO European region: a scoping review’, Sex Education, 21(6), pp. 674–692.

Meredith, R. (2022, January 27). Sex education in schools ‘inadequate’, says commissioner. BBC News NI. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-60147012

Miller, R. (2021, Jun 8). Relationships and Sexuality Education should be standardised, comprehensive, more inclusive – and mandatory. ScopeNI.

National Deaf Children’s Society (2021) Information about deaf children and young people in the UK. National Deaf Children’s Society. London: NDCS.

Nelson, B., Odberg Pettersson, K. (2017) ‘Experiences of Teaching Sexual and Reproductive Health to Students with Intellectual Disabilities: A Phenomenological Study’, The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(5), pp.574-575

NI Assembly. (2024, September 18). Press Release: Education Committee Launches Inquiry into the Provision of RSE in Schools on Wednesday, 18 September 2024. Northern Ireland Assembly.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G.J.J. & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: what is it and why does it matter? In R. Kneyber & J. Evers (eds.), Flip the System: Changing Education from the Bottom Up. London: Routledge.

Roberts, R., Hughes, B., Morgan, L., Kirk, S. and Bloomer, F.K., 2021. Report on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Northern Ireland. The Northern Ireland Abortion and Contraception Taskgroup.

Suter, S., Mccracken, W. and Calam, R. (2009). Sex and Relationships Education: Potential and Challenges Perceived by Teachers of the Deaf. Deafness & Education International. 11(4):211-220

Swinbourne, C. (2012) ‘Communication barriers in sex education put deaf people at risk’, The Guardian, 5 December. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2012/dec/05/sex-education-communication-deaf-people-risk .

Tuchman, G. (2000) The Symbolic Annihilation of Women by the Mass Media. Culture and Politics. Pp.150 -174.

Wilkinson, D. C. (2017) ‘Sex and relationships education: a comparison of variation in Northern Ireland’s and England’s policy-making processes’, Sex Education. 17(6). pp 605-620.

Wilkinson, D.C. (2021) ‘Gender and Sexuality Politics in Post-conflict Northern Ireland: Policing Patriarchy and Heteronormativity Through Relationships and Sexuality Education’, Sexuality Research and Social Policy, pp. 1–14.

United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). (2023). ‘Inquiry concerning the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland under article 8 of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women’. United Nations.

United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child.