An Investigation into the Reasons Behind the Further Expansion of the Attainment Gap for Working-Class University Students Within Northern Ireland After the Pandemic

By Grace Savage

Year 3

Criminology and Sociology Undergraduate Student

Research Proposal – Context and Scope

As an undergraduate student, this research proposal aims to explore the complexities surrounding the widening attainment gap among working-class university students in Northern Ireland, particularly in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is important to clarify that this study remains a proposal and was not conducted. Nonetheless, this proposal lays the groundwork for potential future endeavours in understanding and addressing the persistent challenges faced by working-class students in accessing higher education opportunities in Northern Ireland. It is intended to provide a framework for further research and intervention efforts aimed at promoting equity and inclusivity within the region’s higher education landscape.

Background and Theoretical Framework

The attainment gap within education refers to the persistent disparity in academic performance between different demographic groups (O’Toole and Skinner, 2018). Social class has remained one of the strongest predictors of educational achievement in the United Kingdom (UK). In addition, the social class gap for educational achievement continues to be one of the largest in the developed world (Blundell et al., 2021). Performance gaps, whereby, within subgroups of students there is a gap between what students are expected to do and what they can do emerges early on and highlights social class differences (Deshler, 2005).

The performance gap rarely narrows as children progress in education, with many not being able to make up the lost ground in educational achievement, highlighting the entrenchment of inequality within Britain and Northern Ireland’s schooling system (Betthauser, 2019). This is supported by the Northern Ireland Audit Office (2022), which found that a significant factor that has been linked to the achievement gap is social deprivation in Northern Ireland. The most common partial indicators of social deprivation are average levels of income, unemployment, overcrowding and education (Świgost, 2017).

Kitchen (2001) defines social deprivation as a set of social, economic, and housing problems which concern the residents of a particular area compared to the rest of the population. Alternatively, Smętkowski (2015) defines social deprivation as the lack of access to opportunities and resources which are seen as common in a particular society. This can create a never-ending cycle with intergenerational income mobility being found to be low in the UK compared to most other nations, further impacting educational attainment for the working-class (Blundell, et al., 2021).

The prominence of the issue of educational underachievement is evident within the New Decade New Approach (January 2020). It emphasises the necessary need to examine the evident links between underachievement and socio-economic background (Early et al., 2022). The attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers has stopped closing for the first time in a decade in the UK (UK Parliament, 2020). Policymakers have not succeeded in responding to earlier reports warning of a major loss of momentum in closing the gap stopped before COVID-19 1(Hutchinson et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has had adverse impacts on education and because of remote teaching using various synchronous and asynchronous online platforms ‘learning loss’ and the widening of this ‘learning gap’ among students has grown, particularly for working-class students (Roulston et al., 2020; Goudeau et al., 2021:1275; González and Bonal, 2021:620). Understanding how a pupil’s socio-demographic profile and school-level factors collectively influence educational attainment is crucial for designing and implementing targeted interventions to improve outcomes (Early et al., 2022). Similarly, due to the social significance of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is salient to examine the effects of remote learning on educational attainment (Ilieva, et al., 2021).

Research Aims

The purpose of this study is to identify and understand the barriers to the working-class student’s attainment gap within the university and to develop a set of workable recommendations which may propel institutional change and create an accessible support system for working-class students. This study will investigate the causal factors which create the attainment gap within the historically segregated area of Northern Ireland (Early et al., 2022).

This study raises several research questions for investigation:

- To what extent did COVID-19 affect the attainment gap within Northern Ireland?

- To what extent did financial constraints affect working-class students throughout their education?

- To what extent did COVID-19 affect working-class student’s mental health?

- To what extent did remote learning affect the education gap for working-class students?

- To what extent did working-class students feel a lack of pedagogical support from their university or at home?

Literature Review

Underlying the current debates around educational attainment in Northern Ireland is in [art due to the restricted access to the data needed to explore the wide range of factors that impact educational attainment, particularly for higher education which therefore results in a lack of literature on educational inequalities within Northern Ireland (Early et al., 2022). This may be due to the divide within Northern Ireland as there is a complex history of segregation within the education system and the communities, with a divide between Catholic and Protestant pupils, grammar, and secondary schools as well as single-sex schooling (Burns et al., 2015).

One of the few studies in which this is an exception to is Early et al., (2021) study in Northern Ireland which focuses on the influence of a pupil’s socio-demographic profile and school factors on GCSE attainment outcomes. This study uses qualitative data that linked the Northern Ireland Census (2011), School Leavers Survey and School Census for the first time. The finding highlighted that parental qualifications were the greatest socio-economic predictor of attainment for students, consequently, the higher a mother’s/father’s qualifications, the higher a pupil’s GCSE score.

Similarly, Burns et al., (2015) study on Education Inequalities in Northern Ireland used a mixed methods approach in considering the levels of educational access, attainment, progression and destination across the nine equality grounds (gender, disability, age, dependant status, sexual orientation, racial group, marital status, religious belief and political opinion) as well as other grounds where inequalities in education have been observed.

Moreover, Soira and Horgos (2020) study on ‘Social Class Differences in Students’ Experiences during the COVID-19 Pandemic student experience’ used quantitative methods to examine nine U.S. universities on: students’ transition to remote instruction, the fiscal impact of COVID-19 on students, students’ health and wellbeing during the pandemic, students’ belonging and engagement, and students’ future plans.

This study observed that first-generation students (students whose parents/family have not attended university), were twice as likely to be concerned about paying for their education in fall 2020. As well as experiencing more challenges adapting to online instruction compared to continuing-generation students (students whose parents/family have attended university). This included encountering obstacles related to lack of adequate study spaces and lack of technology necessary to complete online learning. Similarly, first-generation students were also less likely to be able to meet during scheduled virtual class times.

Goudeau, et al., (2021) research on why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap supported that many factors attribute to the accentuation of academic inequalities, including unequal familiarity with school/ university culture and the quality and quantity of pedagogical support received from schools varied according to the social class of families, as well as digital, cultural and structural divides for students which are particularly evident during distance learning.

Methodology

Data Methods

This study will use a mixed methods approach to identify and further analyse educational inequalities for students within the working-class in higher education. Piketty and Saez, (2014:213) noted that when discussions of inequality are confined to purely statistical measures it is “impossible” to clearly identify amongst the manifold dimensions of inequality and mechanisms at play.

This study approach attempts to combine the advantages of the statistical approach with the depth provided by qualitative analysis. Mixed method research utilises pragmatism in which there is a focus on a research problem, using diverse approaches to develop knowledge and solutions to that problem (Creswell, 2009).

Grounded theory will be utilised in this study; grounded theory was developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967), and it is the discovery of theory from data, systematically obtained and analysed in social research (Lambert, 2019). A social constructionist approach to grounded theory will be followed, to address the ‘why questions’ (Charmaz, 2008). This is fitting for this study as it is interested in discovering the causal factors associated with higher education working-class students’ attainment gap, instead of testing existing theory and therefore has an empirical basis which aligns with theory.

Quantitative secondary data from the Department of Education and Learning Northern Ireland, for the years 2016-2021, as well as supplementary data obtained from the Census and the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey will be drawn upon to gather students’ educational inequality within social class in an adapted use of Burns et al., (2015) study on educational inequality in Northern Ireland, however, using advanced statistical software SPSS allowing descriptive analysis (Verma, 2012).

A questionnaire will be created and sent to students within Queen’s University, Belfast, Ulster University including all four campuses Belfast, Coleraine, Magee College and Jordanstown as well its online virtual campus and The Open University in Northern Ireland. It will be used to identify student’s issues and select viable participants for the online semi-structured interviews in the next stage. The primary quantitative data from the questionnaires will be coded on SPSS2. A representative sample of 20 full-time students from the universities mentioned above will be selected as supported by Baker and Edwards (2012) in ‘How Many Qualitative Interviews Is Enough?’

Online web-based semi-structured interviews will also be carried out to gain ‘thick descriptions’ revealing the complexity and are nested in real context (Geertz, 1973 cited in Miles et al., 2018:31). The interviewees will be selected using judgement sampling, from those who meet the eligibility ‘code-frame’ criteria using the questionnaires emailed through the universities previously mentioned to reach the ‘target population’ of Northern Irish working-class higher education students (Fink, 2003). The interviewees will be selected through this non-probability sampling of 14, as supported by Baker and Edwards (2012) which will be adequate to achieve thematic saturation (Weller et al., 2018). The interviews will be conducted using Skype as the effectiveness of this platform for conducting interviews is supported by Gray et al., (2020).

Data Collection

This study will use secondary data for data collection from Government publications and Public Records, using multiple data sources together to gain a more holistic picture (Johnston, 2017). The utilisation of secondary data provides a viable option for researchers as it allows the study analysis of big data, granting for more diverse samples than undergraduate students could conduct, increasing generalisability and saving resources and time (Weston et al., 2019). Quantitative secondary data from the Department of Education and Learning Northern Ireland, for the years 2016-2021, as well as supplementary data obtained from the Census and the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey will be collected.

Within higher education for students in Northern Ireland data: undergraduate and postgraduate enrolments and qualifications; full-time and part-time enrolments and qualifications; subject area enrolments and qualifications; non-continuation data; and leavers’ destinations will be collected. The data will be sourced within the most recent five-year period available, 2016-2021, to track trends over time and to give the most updated picture of existing inequalities. Further, the selected datasets were chosen due to it being the most recent, revised version of the data collected to build upon Burns et al., (2015) study on Educational Inequalities in Northern Ireland which was used to successfully identify educational inequalities in Northern Ireland on behalf of the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland.

Questionnaires and interviews with working-class students were required to fill data gaps as identified by the quantitative data collected. Systematically uncovering the relationship between inequalities and lived experiences with the hope of better capturing the social injustice for working-class students in a holistic model (Perry and Francis, 2010).

A semi-structured web-based questionnaire will be created and after being ethically reviewed by the universities, it will be emailed and sent to students within these Universities. This method will involve self-completion online questionnaires with embedded URLs to collect data (Michaelidou and Dibb, 2006).

The email will disclose the purpose of the study and invite recipients to click on the hypertext link to access the questionnaire, this method will assure anonymity and privacy which can increase response rates. Responses will be received by email in a format which enables their transfer to Microsoft Excel and then SPSS.

The method of a web-based questionnaire was chosen as there are low collection costs, immediate transmission and response as well as provide ease of use (Michaelidou and Dibb, 2006). Despite these advantages, email surveys have several limitations. According to Ranchhod and Zhou (2001), low response rates are associated with the method. Non-response to questionnaires reduces the effective sample size and can introduce bias (Berg, 2005).

The introduction of monetary incentives is one strategy for increasing questionnaire response rates (Sammut et al., 2021). Depending on the study, participants may be offered lesser amounts as a token of appreciation or larger amounts as compensation for their participation. Although, ethical considerations must be considered before incentives are given out to participants, such inducements should be allowed if kept minimal or when the amount of time and effort demanded of participants exceeds a particular level (Sammut et al., 2021). According to Edwards et al. (2005), monetary incentives can boost response to questionnaires; however, the relationship between the amount of money and response is not linear, and this must be considered.

Similarly, the questionnaire mode was chosen as it was the most accessible mode for students, as all students should have access to their emails through their university’s library or their own device. The COVID-19 pandemic has had implications on this choice of mode as face-to-face contact was an issue for both the student and interviewers/fieldworkers’ health and safety (Suich et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic also influenced this choice of mode, as face-to-face contact was an issue for both the student and interviewers/fieldworkers’ health and safety (Suich et al., 2021).

This study will also be using recorded semi-structured interviews for data collection. Permission granted from the universities will be necessary and the email will entail a description of the study and its purpose will be sent out for voluntary participants to partake in online interviews. This synchronous interviewing will use skype application, as the protocol VoIP codes the data, making the data almost untraceable, providing confidentiality for the participant (Bertrand and Bourdeau, 2010). Also, Skype allows recordings of the call in which the interviewer will ask the interviewee for permission to record the conversation, this will also be detailed in the disclosure (Bertrand and Bourdeau, 2010). The recording will be transferred to the cloud and onto a memory stick, it will be stored for 6 months.

The interviewee will be made aware of this within the disclosure emailed beforehand, facilitating for more reliable data transcription (Weller et al., 2018). Similarly, the interviewee will be asked for consent to use quotations from the interview to be included as examples of overarching themes within the study (Rowley, 2012). The semi-structured interview will be limited to 30-40 minutes, and the interviewer will ask the working-class students to discuss education access, achievement, barriers to their education and progression as well as their educational experience. Prompting and probing from the interviewer will occur until saturation reached, which will be facilitated through open ended questions (Weller et al., 2018).

Data Analysis

The data analysis will take place in multiple stages. The quantitative data selected and collected from the secondary data will be transferred onto SPSS software. SPSS can analyse data and produce graphs, nonparametric tests, descriptive statistics, parametric inferential statistical procedures allowing draw inferences about the population based upon the samples of the population input (Cronk, 2019). Enabling a comparative analysis and facilitating the identification of trends relevant to educational inequalities, allowing for conclusion drawing or verification (Miles et al., 2018).

The qualitative data collected from the questionnaire and semi-structured interviews will be transferred into transcriptions from the skype recordings and email responses onto NVivo for data analysis. Qualitative data analysis occurs in three concurrent flows of activity: data condensation, data display and conclusion drawing/ verification (Miles, et al., 2018). Data condensation is the process of selecting, simplifying, and abstracting the data within the interview transcripts, making the data “stronger”.

This study will utilise the NVivo feature of coding ‘nodes’ on imported internal sources such as interviews and questionnaire data. A node is a collection of references about a specific theme or relationship (Bergin, 2011). The method of “Open Coding” will be utilised, which understands coding as a fundamentally subjective and an interactive act of interpretation. As it is ‘open’, codes are not defined in advance but “emerge” from the data, giving the participants influence over the themes that appear. The transcripts will then be recoded after the initial, theoretical, focused, and selective stages of coding, creating theoretical saturation (Miles et al., 2018).

Data Display creates an organised, condensed arrangement of the original data showing analytic reflection and action, in which NVivo facilitates the visualisation of the data collected (Miles, et al., 2018). NVivo contains multiple features to display the data collected, this study will apply the word frequency search queries which allows researchers to view the most frequently appeared words and presents the emerging themes in the data (Wong, 2008). In addition, queries displayed word clouds and word trees on these internal documents display pictorial representation of the internal data facilitating more insight into the research and data (Castleberry, 2014).

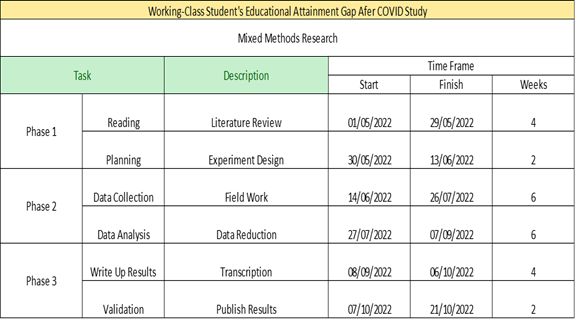

Research Work Plan:

Limitations and Considerations

Ethical Considerations:

This study will follow the British Psychological Society Code of Human Research Ethics which holds the principles: respect for the autonomy, privacy and dignity of individuals, groups and communities, scientific integrity, social responsibility and maximising benefit and minimising harm, (Oates et al., 2021). This study will be reviewed by an ethical committee which will be the Queen’s, Open and Ulster Universities’ local school Research Ethics Committees and have an ethical review as the study fits under the ethical categories A and D for Queen’s University, due to the research collecting data from student participants as well as collecting data from research databases (Queen’s University Belfast, 2022).

Primary data collection will be from the emailed questionnaire/interviews, which will utilise ‘informed consent’ which will be evident in the detailed information declaration in the advanced email sent, as well as before starting the interview, stating the research study, any potential risks to participants and the data protection policy (Bandewar, 2017). Also, all names of individuals and their universities will be anonymised, and pseudonyms will be used within the qualitative data as not to identify the participants themselves in the quotations, which in turn will help guarantee confidentiality (Kitchin, 2003).

Due to the context of the pandemic, interviews were conducted online for ‘Participant and researcher safety’, with participants encouraged to find a private setting, for privacy, and confidentiality (Oates et al., 2021). The ‘public versus private fallacy’ ethical issues for this proposal are a challenge. This is when a false sense of security that online data is anonymous and safe from others and concerns over privacy and confidentiality (Newman et al., 2021). To mitigate the risk, audio, photos, and video-recordings taken of these interviews are discussed within the emailed disclosure under data protection, to protect both the interviewee and interviewer. A participant could record an entire interview and post it on social media (Lobe, 2017).

Strengths and Limitations:

One strength of this study is the focus on higher education attainment within Northern Ireland is currently under-researched within Northern Ireland (Early et al., 2021). Therefore, this research may be beneficial for facilitating institutional change and creating an accessible support system.

The use of public documents and official records is advantageous as utilising high-quality larger datasets, involving larger samples and containing substantial breadth. These larger samples are more representative of the target population and allow for greater validity and more generalisable findings. Allowing analysis of important inequality issues such as this education gap in Northern Ireland which is more time-sensitive (Johnston, 2017). However, secondary data analysis is not without its disadvantages. When applying secondary data analysis to data collected by someone else, a researcher relinquishes control over many important aspects of a study, including the specific research questions that can be answered (Weston et al., 2019).

Similarly, the use of mixed methods is advantageous as it enables a comparative analysis and facilitates the identification of trends relevant to educational inequalities. Thus, serving to triangulate the quantitative data analysis and the perspectives of the students. The interviews in this study have helped to validate and corroborate the eventual research findings and consequently, provides quality assurance as well as providing complementary methods (Bryman, 2007). Although, mixed methods require more expertise to collect and analyse in comparison to using one method. Similarly, requiring extra resources including time and money (Moskal et al., 2015).

Another limitation of this study is that due to COVID-19, the semi-structured interviews must take place online on Zoom. There are many risks associated with this software and online interviews as found by Lobe, et al., (2020). Despite this, some researchers have suggested that online platforms can nearly replicate in-person interactions, sometimes providing more substantial engagement than in-person data collection (Marhefka et al., 2020). As well as that, many people may be inhibited from completing due to disabilities such as dyslexia or visual impairments (O’Connor, 2017).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the proposed study explores prominent issues as it intends to extract the barriers faced by working-class university students in relation to the attainment gap, which have not been addressed in research at present within Northern Ireland. This study is beneficial as within Northern Ireland there is a need for data to be more accessible to explore the wide range of factors that impact educational attainment as supported by the New Decade New Approach. Despite the limitations of this study, the methods were appropriate to triangulate and corroborate the findings as well as complete useful research within a brief period and lack of resources (Bryman, 2007). Research in the future could be expanded to examine further in depth the concept of intersectionality such as ethnicity and working-class within Northern Ireland or the prominent issue of Northern Irish Protestant working-class males falling behind academically. This study hopes to have provided a thorough understanding of the problems faced by working-class students within the university.

References:

Baker, S & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? Expert voices and early career reflections on sampling and cases in qualitative research. National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM) Review Paper, Available online at: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf

Bandewar, S.V., 2017. Cioms 2016. Indian J Med Ethics, 2, pp.138-40.

Berg, N., 2005. Non-response bias.

Bergin, M., 2011. NVivo 8 and consistency in data analysis: Reflecting on the use of a qualitative data analysis program. Nurse researcher, 18(3).

Bertrand, C. and Bourdeau, L., 2010. Research interviews by Skype: A new data collection method. In Paper Presented at the Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, Madrid, Spain.

Betthäuser, B.A., 2019. The effect of the post-socialist transition on inequality of educational opportunity: Evidence from German unification. European Sociological Review, 35(4), pp.461-473.

Blundell, R., Cribb, J., McNally, S., Warwick, R. and Xu, X., 2021. Inequalities in education, skills, and incomes in the UK: The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://ifs. org. uk/inequality/inequalities-in-education-skills-and-incomes-in-the-uk-theimplications-of-the-covid-19-pandemic.

Bozkurt, A., Jung, I., Xiao, J., Vladimirschi, V., Schuwer, R., Egorov, G., Lambert, S., Al-Freih, M., Pete, J., Olcott Jr, D. and Rodes, V., 2020. A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), pp.1-126.

Bryman, A., 2007. Barriers to integrating quantitative and qualitative research. Journal of mixed methods research, 1(1), pp.8-22.

Burns, S., Leitch, M. and Hughes, J., 2015. Education inequalities in Northern Ireland: Final report to the equality commission for Northern Ireland.

Castleberry, A., 2014. NVivo 10 [software program]. Version 10. QSR International; 2012.

Charmaz, K., 2008. Constructionism and the grounded theory method. Handbook of constructionist research, 1(1), pp.397-412.

Ciotti, M., Ciccozzi, M., Terrinoni, A., Jiang, W.C., Wang, C.B. and Bernardini, S., 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences, 57(6), pp.365-388.

Creswell, J.W., 2009. Mapping the field of mixed methods research. Journal of mixed methods research, 3(2), pp.95-108.

Cronk, B.C., 2019. How to use SPSS®: A step-by-step guide to analysis and interpretation. Routledge.

Deshler, D., 2005. A closer look: Closing the performance gap. Retrieved December.

Early, E., Miller, S., Dunne, L. and Moriarty, J., 2022. The influence of socio-demographics and school factors on GCSE attainment: results from the first record linkage data in Northern Ireland. Oxford Review of Education, pp.1-21.

Edwards, P., Cooper, R., Roberts, I. and Frost, C., 2005. Meta-analysis of randomised trials of monetary incentives and response to mailed questionnaires. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(11), p.987.

Fink, A., 2003. How to sample in surveys (Vol. 7). Sage.

González, S. and Bonal, X., 2021. COVID‐19 school closures and cumulative disadvantage: Assessing the learning gap in formal, informal and non‐formal education. European journal of education, 56(4), pp.607-622.

Goudeau, S., Sanrey, C., Stanczak, A., Manstead, A. and Darnon, C., 2021. Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap. Nature human behaviour, 5(10), pp.1273-1281.

Gray, L.M., Wong-Wylie, G., Rempel, G.R. and Cook, K., 2020. Expanding qualitative research interviewing strategies: Zoom video communications. The Qualitative Report, 25(5), pp.1292-1301.

Hinton, P.R. and McMurray, I., 2017. Presenting your data with SPSS explained. Taylor & Francis.

Hinton, P.R., McMurray, I. and Brownlow, C., 2014. SPSS explained. Routledge.

Hutchinson, J., Reader, M. and Akhal, A., 2020. Education in England: annual report 2020.

Ilieva, G., Yankova, T., Klisarova-Belcheva, S. and Ivanova, S., 2021. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ learning. Information, 12(4), p.163.

Johnston, M.P., 2017. Secondary data analysis: A method of which the time has come. Qualitative and quantitative methods in libraries, 3(3), pp.619-626.

Kasar, A.B., Reddy, M., Wagh, R. and Deshmukh, Y., 2021. Current Situation of Education field due to Corona Virus Disease 19. Paideuma Journal, 14(2), pp.44-51.

Kitchen, P., 2001. An approach for measuring urban deprivation change: the example of East Montréal and the Montréal Urban Community, 1986–96. Environment and Planning A, 33(11), pp.1901-1921.

Kitchin, H.A., 2003. The Tri-Council Policy Statement and research in cyberspace: Research ethics, the Internet, and revising a ‘living document’. Journal of Academic Ethics, 1(4), pp.397-418.

Lambert, M., 2019. Grounded theory. Practical research methods in education: An early researcher’s critical guide, pp.132-141.

Lobe, B., 2017. Best practices for synchronous online focus groups. In A new era in focus group research (pp. 227-250). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Lobe, B., Morgan, D. and Hoffman, K.A., 2020. Qualitative data collection in an era of social distancing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, p.1609406920937875.

Lu, H., Stratton, C.W. and Tang, Y.W., 2020. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. Journal of medical virology, 92(4), p.401.

Marhefka, S., Lockhart, E. and Turner, D., 2020. Achieve research continuity during social distancing by rapidly implementing individual and group videoconferencing with participants: key considerations, best practices, and protocols. AIDS and Behavior, 24(7), pp.1983-1989.

Michaelidou, N. and Dibb, S., 2006. Using email questionnaires for research: Good practice in tackling non-response. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and analysis for Marketing, 14(4), pp.289-296.

Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M. and Saldaña, J., 2018. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Sage publications.

Moskal, B.M., Reed, T. and Strong, S.A., 2015. Quantitative and mixed methods research: Approaches and limitations. In Cambridge Handbook of Engineering Education Research (pp. 519-534). Cambridge University Press.

Newman, P.A., Guta, A. and Black, T., 2021. Ethical considerations for qualitative research methods during the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergency situations: navigating the virtual field. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, p.16094069211047823.

Northern Ireland Audit Office. 2022. Closing the Gap – Social Deprivation and links to Educational Attainment. [online] Available at: <https://www.niauditoffice.gov.uk/publications/closing-gap-social-deprivation-and-links-educational-attainment> [Accessed 3 May 2022].

O’Connor, H. and Madge, C., 2017. Online interviewing. The SAGE handbook of online research methods, 2, pp.416-434.

Oates, J., Carpenter, D., Fisher, M., Goodson, S., Hannah, B., Kwiatowski, R., Prutton, K., Reeves, D. and Wainwright, T., 2021, April. BPS Code of Human Research Ethics. British Psychological Society.

O’Toole, B. and Skinner, B., 2018. Closing the achievement gap: challenges and opportunities. Minority Language Pupils and the Curriculum: Closing the Achievement Gap, p.3.

Perry, E. and Francis, B., 2010. The social class gap for educational achievement: A review of the literature. RSA Projects, pp.1-21.

Piketty, T. and Saez, E., 2014. Inequality in the long run. Science, 344(6186), pp.838-843.

Pokhrel, S. and Chhetri, R., 2021. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher education for the future, 8(1), pp.133-141.

Queen’s University Belfast., 2022. Ethics | Research | Queen’s University Belfast. [online] Available at: <https://www.qub.ac.uk/Research/Governance-ethics-and-integrity/Ethics/> [Accessed 3 May 2022].

Ranchhod, A. and Zhou, F., 2001. Comparing respondents of e‐mail and mail surveys: understanding the implications of technology. Marketing Intelligence & Planning.

Roulston, S., Taggart, S. and Brown, M.F., 2020. Parents Coping with Covid-19: Global Messages from Parents of Post-Primary Children across the island of Ireland.

Rowley, J., 2012. Conducting research interviews. Management research review.

Sammut, R., Griscti, O. and Norman, I.J., 2021. Strategies to improve response rates to web surveys: a literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 123, p.104058.

Soria, K.M., Horgos, B., Chirikov, I. and Jones-White, D., 2020. First-generation students’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Suich, H., Yap, M. and Pham, T., 2021. Coverage bias: the impact of eligibility constraints on mobile phone-based sampling and data collection. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, pp.1-12.

Świgost, A., 2017. Approaches towards social deprivation: Reviewing measurement methods. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, (38), pp.131-141.

Tarkar, P., 2020. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(9), pp.3812-3814.

UK Parliament (2020) COVID-19 and the disadvantage gap, Available at: https://post.parliament.uk/covid-19-and-the-disadvantage-gap/#:~:text=The%20Education%20Policy%20Institute%202020%20report%20has%20indicated,the%20gap%20is%20no%20longer%20closing%20at%20all. [Accessed: 27/10/23].

Verma, J.P., 2012. Data analysis in management with SPSS software. Springer Science & Business Media.

Weller, S.C., Vickers, B., Bernard, H.R., Blackburn, A.M., Borgatti, S., Gravlee, C.C. and Johnson, J.C., 2018. Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PloS one, 13(6), p.e0198606.

Weston, S.J., Ritchie, S.J., Rohrer, J.M. and Przybylski, A.K., 2019. Recommendations for increasing the transparency of analysis of preexisting data sets. Advances in methods and practices in psychological science, 2(3), pp.214-227.

Wong, L.P., 2008. Data analysis in qualitative research: A brief guide to using NVivo. Malaysian family physician: the official journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia, 3(1), p.14.

- In December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown origin was reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China (Lu, Stratton and Tang, 2020). The WHO declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020, as a result of the thousands of deaths brought on by COVID-19 and the worldwide spread of SARS-CoV-2 (Ciotti et al., 2020). The pandemic significantly disrupted the growth of countries where new cases of coronavirus were reported (Tarkar, 2020). Many countries took various measures such as lockdown, workplace non-attendance, school closure, suspension of transport facilities to control the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic (Kasar et al., 2021). The COVID-19 epidemic had an impact on around 1.6 billion students across more than 200 nations, estimated to have caused the worst disruption to educational systems in recorded human history (Bozkurt et al., 2020). Closing of schools, institutions, and other learning facilities has affected more than 94% of students globally (Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021).

↩︎ - SPSS is an easy-to-use software package for data analysis and visualisation (Hinton, McMurray and Brownlow, 2014). It has the ability to perform analysis, ranging from adding up results to complex statistical procedures (Hinton and McMurray, 2017). ↩︎