“A silly girl who was causing trouble for the lads” Melissa Beggs – 3rd Year Criminology

Abstract

In 2018, Ireland and Ulster rugby players Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding went to trial after being accused of sexual assault. The trial garnered much media attention in their hometown of Belfast due to the celebrity status of both defendants. This study aims to assess the presence of rape myths and victim-blaming in the newspaper reporting of the Belfast’ rugby rape trial’. This is considered through two questions. These were: what rape myths were perpetuated about Jackson and Olding, and what rape myths were perpetuated about the victim? The research study uses quantitative and qualitative methods to use a mixed-method approach to content analysis. The database LexisNexis is used to obtain the newspaper articles with a sample of 178 articles from The Belfast Telegraph Online used for the initial quantitative analysis. The search parameters were refined for a final sample of 24 newspaper articles for qualitative analysis. Findings from the study show that the defendants and their lawyers are featured heavily in the newspaper articles with little voice given to the victim.

Furthermore, continued reference to the defendant’s successful rugby careers was also noted, whilst there was victim-blaming rhetoric questioning why the girl did not run away or scream for help. In conclusion, this study found that newspapers indirectly perpetuated rape myths and victim-blaming, as they gave a disproportionate voice to the defendants. This consequently meant that newspapers repeated the rape myths perpetuated by the defendants and the defendants’ lawyers.

Introduction

Despite only representing a small minority of sexual assault cases, celebrity cases often present a focal point for the media reporting of sexual assault (Saks et al., 2017). This is due to the newsworthiness surrounding celebrities and sex, meaning that these cases have increased public interest and readership (Jewkes, 2015). In 2018 Northern Ireland had its own celebrity sexual assault case with the trial of Ulster and Ireland rugby players Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding. In June 2016, the players faced accusations of raping a woman in Jackson’s house after a night out at the Ollies Nightclub in Belfast (Killean et al., 2021). As a result, it was often dubbed the ‘Rugby Rape Trial’, a case that dominated the media, with increased reporting in the accused athletes’ hometown of Belfast (Killean et al., 2021). The trial commenced in January 2018 with four defendants; however, this research will focus primarily on Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding. First, this is due to their celebrity status as they were well-known before the trial began. Secondly, both Jackson and Olding were on trial for rape. In contrast, the other two defendants, Blane McIlroy and Rory Harrison, were on trial for exposure and perverting the course of justice. The defendants were found not guilty, a verdict that divided opinion across the country (McKay, 2018).

Rape myths are ‘prejudicial, stereotyped or false beliefs about rape, rape victims and rapists’ (Burt, 1980: 217). These myths encourage victim-blaming attitudes and are spread through society as the media reporting of sexual assault often perpetuates these rape myths (Benedict, 1992; Peterson, 2019). A study by Pica et al. (2017) found media reporting may contain higher instances of rape myths when the accused is a star athlete. This research, therefore, aims to investigate the presence of rape myths in the local media reporting of the ‘rugby rape trial’. This study will consider the following questions:

- What rape myths were perpetuated about Jackson and Olding?

- What rape myths were perpetuated about the victim?

Methodology

This research will undertake mixed methods content analysis using quantitative and qualitative methods to assess the presence of rape myths. A content analysis is an approach to analysing documents and texts that aims to determine the presence of predetermined categories in a systematic and replicable manner (Bryman, 2008). A quantitative approach is concerned with measuring the phenomenon reported, whereas, in this study, a qualitative analysis will consider the language used by the media. A quantitative analysis alone cannot understand how language is used and only gives a surface description (Greer, 2013). Hence, Creswell & Clark (2007) state that a mixed-methods approach allows for a better understanding of the research subject than the methods would allow if carried out separately. Therefore, this study will use qualitative and quantitative methods to research the presence of keywords and themes in the newspaper reporting of the trial. This research used inductive and deductive approaches to create a coding frame (Lune and Berg, 2017). Using existing literature on rape myths, two coding frames were created for the quantitative and qualitative analysis. The research design used predetermined codes while identifying emerging codes during the analysis. A coding frame allowed written data to be converted into numeric data for analysis (Lewis-Beck et al., 2004). Having consulted the literature on rape myths and their presence in media reporting, the five most evident rape myths were noted and used to create a quantitative coding frame (Peterson et al., 2019; Lees,1996; Saks et al., 2017; Burt, 1998). The coding frames enabled the research to code for the presence of common rape myths in the media reporting of the trial (see Appendix I and Appendix II). This was done by determining words related to each rape myth which were then searched for in the newspapers to assess the presence of rape myths. For example, the word’ regret’ was searched to determine the presence of the rape myth that the victim is lying as she regrets it. A coding frame was created for qualitative analysis, allowing for the context in which the words were said to be explored.

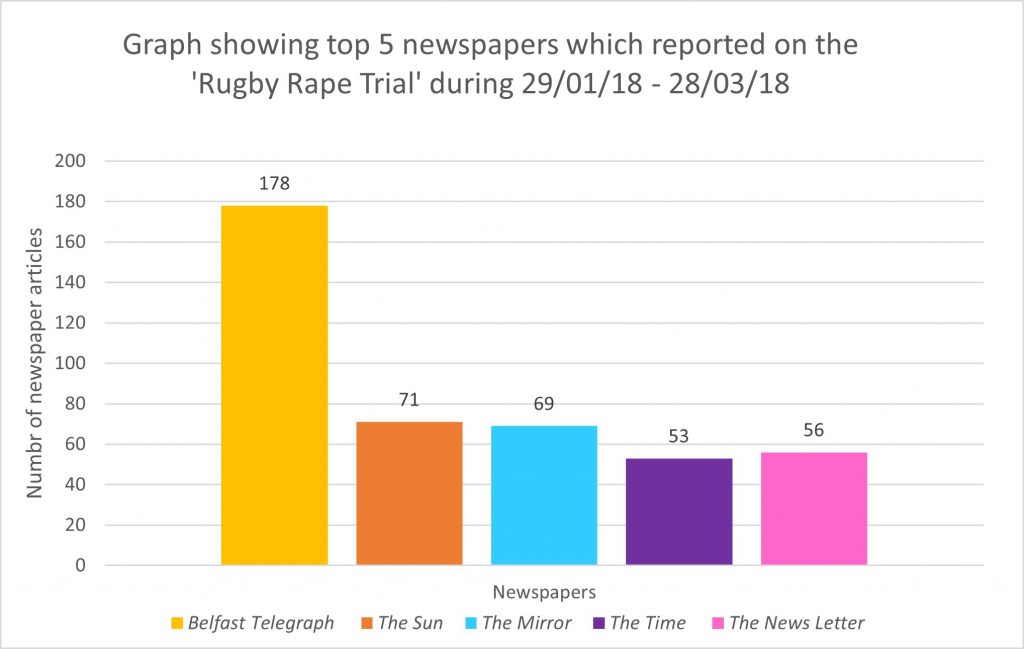

Graph 1

To conduct this study, the database LexisNexis was used to source newspaper articles relating to the topic. The search terms ‘rape’ AND ‘Paddy Jackson’ OR ‘Stuart Olding’ were searched anywhere in the text during the trial period of 29 January 2018 to 28 March 2018 within Great Britain and Northern Ireland. This produced 1,097 publications. This number includes online and print newspapers, news transcripts, press releases, and video and audio files. This study chose to focus on the reporting in The Belfast Telegraph due to the spatial proximity it had to the case, as it was the local newspaper of where the trial took place, and cultural proximity, as the accused were from Belfast and played for the Ulster and Irish rugby teams (Jewkes, 2015).

Further, as depicted in graph 1, The Belfast Telegraph reported on the trial with a significant margin over any other newspaper. Therefore, the initial sample of 1,097 was refined to only include articles from The Belfast Telegraph. The articles were from The Belfast Telegraph Online as it is the only version LexisNexis holds.

This provided a sample of 178 newspaper articles. This initial data formed the quantitative analysis of the newspapers, in which specific terms were searched within the articles that point towards the presence of rape myths (see Appendix I). For a more detailed qualitative analysis, the data were refined to exclude articles less than 500 words. This allowed for a sample of 104 newspaper articles, with every 4th article being chosen for analysis. This is known as a stratified random sample, and this method was selected as it ensures no bias in choosing articles and increases validity (Lune and Berg, 2017). In addition, two articles were excluded as they were duplicates, leaving a final sample of 24 newspaper articles.

Findings and Analysis

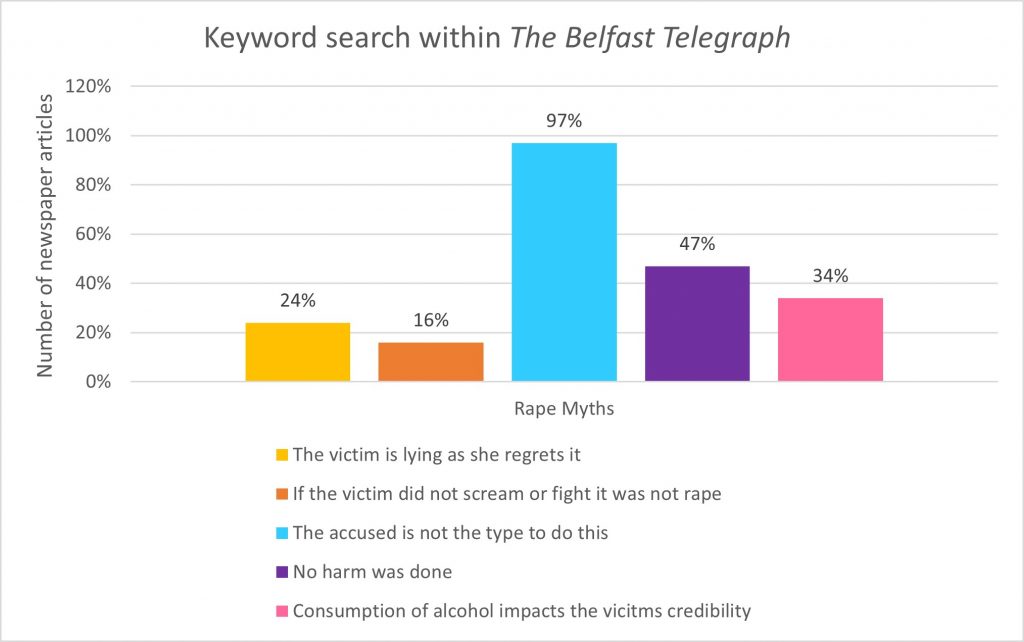

This section includes the findings from the qualitative and quantitative analysis. Five rape myths were found in the text of the Belfast Telegraph online reporting. This study utilised the quantitative results in graph two and undertook a qualitative analysis to assess the themes of each of these rape myths in the sample of 24 newspapers. The quantitative analysis demonstrated that the rape myth that the accused was not the type of person to do this was the most prevalent. The section is set up thematically, with each paragraph addressing the presence of each rape myth.

Graph 2

The victim is lying as she regrets it

Graph 2 shows the search results for keywords that indicate the presence of rape myths within The Belfast Telegraph. A theme in the reporting of the trial was that the victim lied as she regretted the incident. This was present in 24% of the articles. A qualitative analysis showed that this rape myth was perpetuated primarily by Rory Harrison and Blane McIlroy when the defence cross-examined them. As Harrison states of the allegations, ‘I didn’t believe it. I thought she had maybe done something and then regretted it.’ (The Belfast Telegraph, 2018A). The newspaper articles continually quote such phrases without challenging what the accused said. Reporting a sexual assault and going through the criminal justice system is an invasive and challenging process for victims (Lees, 1996). The newspapers did not mention this, which repeated the accused’s words in the trial without any critical analysis.

If the victim did not scream or fight, it was not rape

The least present theme (16%) in the reporting was continued reference to how the victim did not scream or fight. Through reference to this, it is perpetuating the myth that when the victim does not scream or fight back, it is not rape (Peterson, 2019). A qualitative analysis demonstrated this rape myth was repeatedly referred to by the defence barristers, who were the dominant source of information in the articles. The defence overtly propagated this rape myth by stating, ‘there were 3 middle-class girls downstairs … Why didn’t she scream the house down?’ (O’Boyle, 2018A). Qualitative analysis also showed that the defence did this covertly through the continued reference and emphasised that three other girls in the house did not hear any distressing sounds. Victims of sexual assault may not fight or scream due to fear or shock (Lees, 1996). Any newspaper article did not mention this. Resembling the above rape myth demonstrates how the newspaper articles were repeating the rape myths, this time perpetrated by the defence, without any critical analysis of what was being argued.

The accused is not the type to do this

Graph 2 shows the theme that was the most prevalent (97%) in the newspaper articles was that Olding and Jackson were ‘star’ rugby players, who were ‘good guys’ and the ‘last person’ anyone would think would commit such a crime. This emphasises the myth that the accused are not the type to do this. An evident theme was that the newspaper articles referred to the pair as ‘international rugby stars’ several times (McDonald, 2018A). This puts their rugby career as their dominant status rather than two men on trial for sexual assault. Having completed a qualitative analysis of the newspaper articles, it was also evident that the headlines and content of the articles centred around Jackson and Olding. Their rugby careers were frequently mentioned, along with their account of the night and articles reiterating the defence’s claims that the two were the real victims in this case, with their celebrity status being the reason they were prosecuted. The defence exemplifies this,’…it was the very status as a famous sportsman that drove the decision to prosecute in the first place’ (The Belfast Telegraph, 2018B). This emphasises that the accused were not the type to do this as it argues that their celebrity status was the reason for the prosecution rather than the evidence presented by the prosecution and victim.

No harm was done

In contrast to the above, less than half (47%) of the newspaper articles contain the term ‘victim’. The qualitative analysis reflected this theme as relatively few articles gave a voice to the victim, or when the victim was mentioned, she was primarily referred to as the ‘complainant’ or ‘woman’ (O’Boyle, 2018B). This can be compared to the accused, who, only second to their defence barristers, present the main sources of information for the articles. Therefore, the accused’s account was given prominence over the victim’s, a recurring theme. The dominance of the accused’s account of the night further perpetuates the myth no harm was done as the accused emphasise how the victim had previously been flirting with them and how the woman ‘could have left if she wanted…but she didn’t’ (McCurry, 2018). Entman (1993: 54) argues that when framing a story, what is excluded ‘may be as critical as the inclusions in guiding the audience’. Therefore, devoting so much content to the accused and other aspects of their life, such as their rugby career, minimises the potential impact of the alleged crime on the victim. This downplays the seriousness of the offence (Waterhouse-Watson, 2017). Therefore, the dominance of the defence barristers and the accused voice causes the victim and their experience to become an afterthought. This reinforces the rape myths that suggest no harm was done (Burt, 1998).

Consumption of alcohol impacts the victim’s credibility

29% of articles referenced the victim and the accused being out and drinking the night of the incident. A theme that emerged in the qualitative analysis was although the accused and the victim admitted to having consumed alcohol, the defence presented this as something positive on behalf of the accused for showing’ warts and all’ (McDonald, 2018B). However, it was presented as the victim’s downfall with the defence using her alcohol intake to attack the credibility of her account as they stated that she had ‘memory gaps’ which she then filled with ‘activity’ (The Belfast Telegraph, 2018C). This is reflected in the headline, ‘ Woman in rugby rape trial denies alcohol clouded her memory…’ (The Belfast Telegraph, 2018C). Although this denounced that she incorrectly remembers the incident, it was still the headline. This sets the tone for the article that the victim could be lying. The newspaper articles do not query why the credibility of those accused was not brought into question due to their alcohol intake. Furthermore, when acting as a witness for Jackson and Olding, several articles mention Harrison admitting to having ‘memory gaps’ due to intoxication on the night of the incident (The Belfast Telegraph, 2018A). However, this was only mentioned in the main body of the articles. Contrastingly the headlines revolved around how shocked he was over the allegations against his friends. This also emphasises that the accused was not the type to do this. Therefore, the possibility of the victim having incorrectly remembered the night was given more prominence in the newspaper coverage than one of the accused admitting to having memory gaps. The newspaper reporter’s decision to give prominence to the voice of the defence barristers and the accused without any critical analysis has perpetuated the rape myth that the victim drank too much and incorrectly remembers the night.

Conclusion

This research has demonstrated that the ‘rugby rape trial’ was a newsworthy story that was of priority to a Northern Irish audience due to the news values of celebrity status and the proximity of the crime (Jewkes, 2015). However, a mixed-methods approach to analysis has shown that rape myths were present in reporting the ‘rugby rape trial’. These myths were perpetuated by the defence and accused, with both serving as the main source of information for the articles. The newspaper reporters then repeated these rape myths without critically analysing what the defence and accused were purporting. This is in line with previous research that has found that media reporting of sexual assault trials overuse quotations from defence barristers who attack the truthfulness of the victim (Lees, 1996; Dowler, 2006). Therefore, while the newspaper reporters did not produce the myths, the reporters were reproducing the myths by giving the defence, and the accused a disproportionate voice compared to the victim and prosecution.

Reference list

Benedict, H. (1992) Virgin or vamp: How the press covers sex crimes, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bryman, A. (2008) Social Research Methods, 3rd edn., Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burt, M. (1980) ‘Cultural myths and supports for rape’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), pp. 217-230.

Burt, M. (1998) ‘Rape Myths ‘, in Odem, M. E. and Clay-Warner, J. (ed.) Confronting Rape and Sexual Assault. Oxford: SR Books, pp. 129-145.

Chibnall, S. (1977) Law-and-order news: an analysis of crime reporting in the British press, London: Tavistock Publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. (2007) Designing and conducting mixed methods research, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Dowler, K. (2006) ‘Sex, lies, and videotape: the presentation of sex crime in local television news’, Journal of Criminal Justice, 34(4), pp. 383-392.

Entman, R. M. (1993) ‘Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm’, Journal of Communication, 43(4), pp. 51-58.

Greer, C. (2013) ‘Crime and media: understanding the connections’, in Hale, C., Hayward, K., Wahidin, A. and Wincup, E. (ed.) Criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 143-165.

Jewkes, Y. (2015) Media & crime, 3rd edn., Los Angeles: SAGE.

Killean, R., Dowds, E. and McAlinden, A. (2021) ‘Sexual offence trials in Northern Ireland’, in Killean, R., Dowds, E. and McAlinden, A. (ed.) Sexual violence on trial: local and comparative perspectives. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 3-21.

Lees, S. (1996) Carnal Knowledge: rape on trial, London: Hamish Hamilton.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Bryman, A., & Futing Liao, T. (2004) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods, California: SAGE Publications.

Lune, H. & Berg, B. L. (2017) Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 9th edn., Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

McCurry, C. (2018) ‘Jackson and Olding trial: I didn’t rape her, upset Paddy told police’, The Belfast Telegraph, 24 February.

McDonald, A. (2018A) ‘Jackson and Olding trial: Rugby star Paddy Jackson’ shocked and horrified’ by rape allegations’, The Belfast Telegraph, 23 February.

McDonald, A. (2018B) ‘Rugby rape trial: Stuart Olding’ telling the truth… warts and all’ says defence barrister’, The Belfast Telegraph, 21 March.

McKay, S. (2018) ‘How the ‘rugby rape trial’ divided Ireland’, The Guardian, 4 December. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/dec/04/rugby-rape-trial-ireland-belfast-case. (Accessed 10/04/21).

O’Boyle, C. (2018A) ‘Rugby rape trial: Authorities’ let down’ Stuart Olding by failing to query evidence, jury told;’, The Belfast Telegraph, 22 March.

O’Boyle, C. (2018B) ‘Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding rape trial doctor doesn’t know if sex was consensual, court told’, The Belfast Telegraph, 21February.

Peterson, K. (2019) ‘Victim or Villain?: The Effects of Rape Culture and Rape Myths on Justice for Rape Victims ‘, Valparaiso University Law Review, 53(2), pp. 467-508.

Pica, E., Sheahan, C., & Pozzulo, J. (2017) ‘ “But he’s a star football player!” How social status influences mock jurors’ perceptions in a sexual assault case’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(19/20), pp. 3963-3985.

Saks, M., Ackerman, A. and Shlosberg, A. (2017) ‘Rape Myths in the Media: A Content Analysis of Local Newspaper Reporting in the United States’, Deviant Behavior, 39(9), pp. 1-10.

The Belfast Telegraph (2018A) ‘Friend of rape accused rugby player shocked over allegations; He was asked about a message hours later in which the complainant stated what happened had not been consensual’, The Belfast Telegraph, 10 March.

The Belfast Telegraph (2018B) ‘High tension in court as defendants awaited verdict in rape trial; Paddy Jackson, Stuart Olding, Blane McIlroy and Rory Harrison were acquitted following a nine-week trial’, The Belfast Telegraph, 28 March.

The Belfast Telegraph (2018C) ‘Woman in rugby rape trial denies alcohol clouded her memory; Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding deny raping the same woman’, The Belfast Telegraph, 12 February.

Waterhouse-Watson, D. (2017) ‘”Our Fans Deserve Better”: Erasing the Victim of Blake Ferguson’s Sexual Crime’, Communication & Sport, 6(4), pp. 436-456.

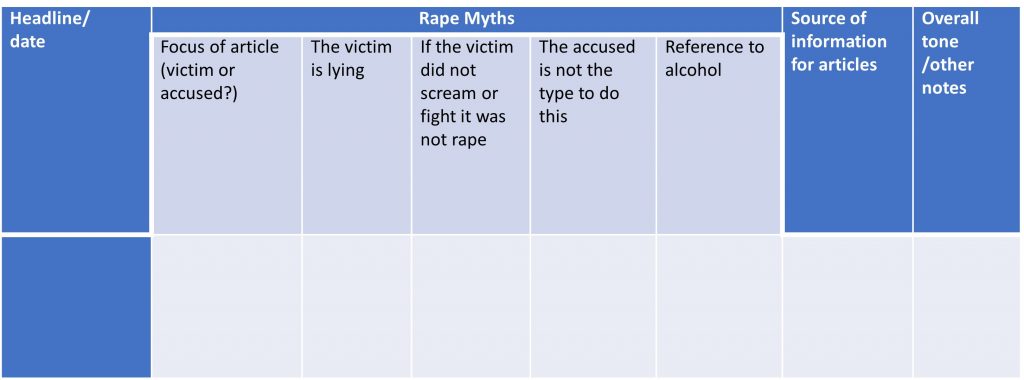

Appendix I

Coding Frame for quantitative analysis

Table 1– This table was informed by previous studies and informational websites. These were Peterson et al. (2019), Lees (1996), Saks et al., (2017) and Burt (1998).

| About | Rape Myth | Words searched |

| Victim | The victim is lying as she regrets it | Regret |

| Victim | If the victim did not scream or fight it was not rape | Scream OR fight |

| Accused | The accused is not the type to do this | Star OR rugby OR generous OR ‘last person’ OR ‘good guy’ |

| Victim | Consumption of alcohol impacts victim’s credibility | Drink OR drunk OR alcohol |

| Victim/accused | No harm was done/ it is not that serious | Victim |

Appendix II

Coding Frame for qualitative analysis

Table 2- This table was informed by previous studies and informational websites. These were Peterson et al. (2019), Lees (1996), Saks et al., (2017) and Burt (1998).