A critical analysis into the methodology of the collection and compilation of domestic abuse statistics in Northern Ireland over a ten-year period (2011-2020). Chris Beaumont -1st Year Criminology

Introduction

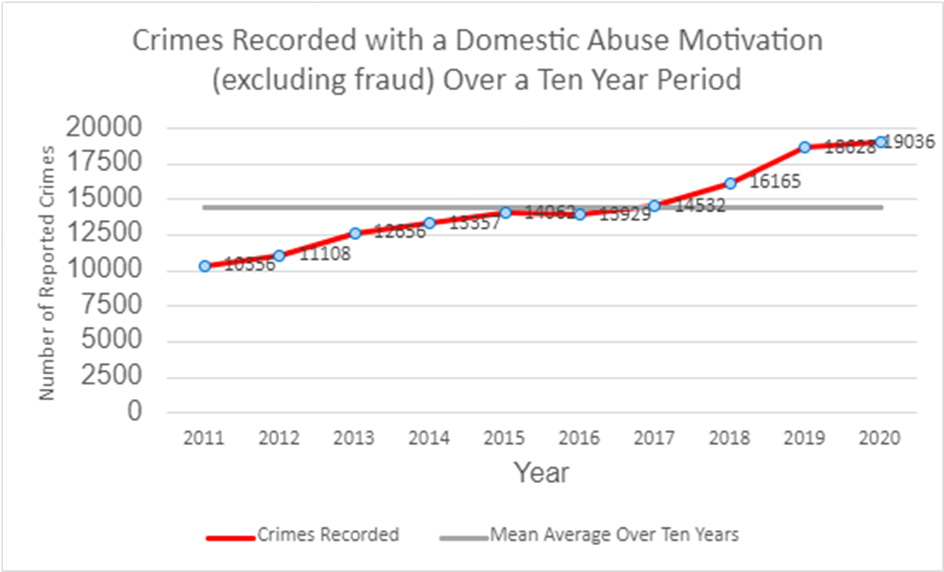

The graph above details crimes which have been recorded as having a domestic abuse motivation over a ten-year period in Northern Ireland from 2010/11 – 2020/21. We can see that these crimes have increased between 2019-2020 with a brief plateau during 2015-2016. It is crucial to consider population size when comparing rates to accurately assess trends in domestic abuse incidents, as this provides a better understanding of the number of individuals at risk during a given period, however this piece instead focuses on the number of recorded incidents. Within this analysis of domestic abuse statistics, there will be a discussion of both the historical and modern definition of domestic abuse including acknowledgement of the updated Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021. By highlighting the updated act there will be an analysis into the impact this has had on rising crime statistics over a ten-year period. There will be a direct conclusion that highlights that whilst quantitative analysis of statistics serves a purpose within criminology, statistical analysis can be limited and vulnerable to manipulation and misrepresentation. Due to the dark figure within crime statistics quantitative analysis in criminology can be limited and prone to manipulation and misrepresentation, while official data often fails to capture the full extent of domestic violence incidences. The reliance on statistical analysis alone may overlook important contextual factors and nuances contributing to domestic violence (Stamenković, 2021).

Presentation of a perpetrator

Gabriel Tarde (1843-1904) spearheaded the switch between classicism and positivism (Renneville, 2007). The premise that someone is born a criminal (Lombroso, 1876) has evolved into a social process theory-centered approach (Siegel, 2000). The belief that the genetic make-up of an individual is involved with their likelihood to engage in criminal activity, has become historical. Due to this evolution, a positivist approach has evolved (Renneville, 2007).

With a modern understanding of domestic abuse and crime, Icheku and Graham (2017) have begun to investigate a perpetrators’ socialization, morals as well as their beliefs. Researchers have since theorized that no one is born a criminal, however how individuals are shaped through life experiences over time may increase and influence an individual’s chances of offending (Roberts et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2011).

Responsibility to record

Alvarez-Berastegi and Hearty (2019) have theorized that, as an individual within society, there is a personal responsibility in becoming a victim of domestic abuse (Carter, 1999; Krane, 2003). It should be acknowledged that when the legal definition of domestic abuse changed, the phenomenon of “crime displacement” also took place. Due to this how both the individual and general deterrents, along with how society and policymakers can investigate, tackle, and prevent it, changes also (Kukreja & Pandey, 2023).

Gaslighting, like bullying, became a crime under Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act (2015) [Serious Crime Act 2015, c. 9], which addresses controlling or coercive behavior (CCB). After the introduction of a new law, the number of CCB offenses reaching first hearings at magistrates’ courts has shown a significant increase. This rise can be attributed to a heightened awareness among the police, Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), other agencies, and the public, regarding the recognition and reporting of coercive and controlling behavior. However, the true extent of these cases may be underestimated due to implementation challenges and changes in counting rules associated with the new legislation (Office for National Statistics, 2017).

Within Northern Ireland currently (Police Service of Northern Ireland & Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2021), there is no current representative data highlighting law change. However, understanding changes in law and how crimes are recorded, both of which affect recorded data, is crucial (Hicks et al., 2013).

Although legislation was passed in 2021, news reports highlight that the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) has experienced a reported increase of 100 calls per month since implementation in 2022 (McGonagle, 2022). Delays in creating laws to prevent crime highlight shortcomings from a devolved government (Reid, 2022). Until 2021, domestic abuse was covered by the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, later updated by The Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021 (McQuigg, 2021). Although this is not represented in the graph above, it is a consideration that should not be ignored as the delay in making gaslighting and coercive control illegal in Northern Ireland may have created a gap in protection for victims of these behaviors. By addressing this gap, the change in law acknowledged how crucial it was to close the gap as a means to safeguard the safety and well-being of individuals impacted by gaslighting and coercive control in Northern Ireland (Stover, 2005). Douglas (2015) conducted research in Australia, by analyzing the need for a specific domestic abuse offense. In her study, she focuses on the introduction of a “controlling or coercive” behavior offense in English and Welsh law in 2015 and explores its applicability of this change in law as a means to addressing domestic violence within Australia.

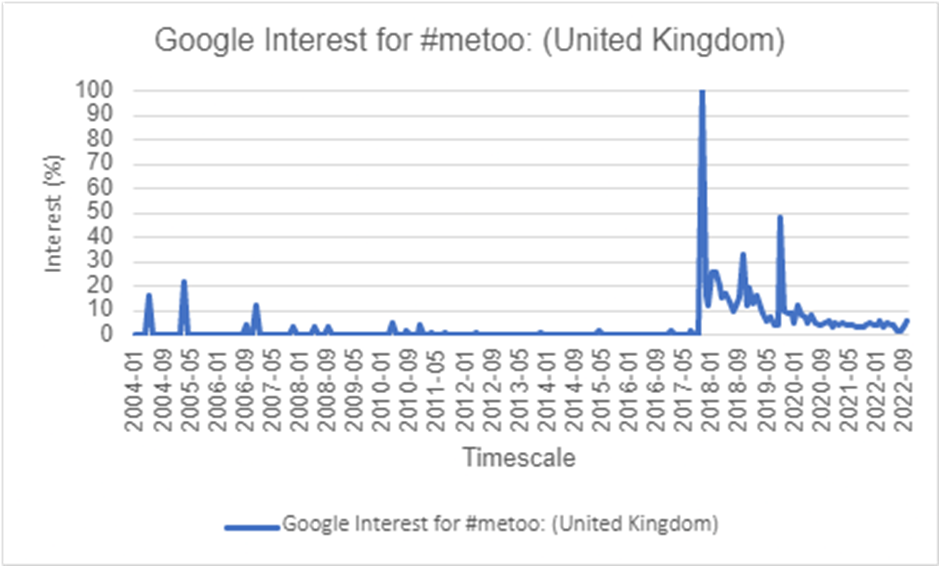

The graph shows a dramatic increase in crimes with domestic abuse between 2017-2020. This rise in domestic abuse can be attributed, in part, to social movements such as the #MeToo movement, initiated by activist Tarana Burke in 2006 (Julios, 2022).).This came to the forefront of international media and social justice campaigns in 2017 by empowering victims of domestic abuse to report sexual assault-based and related incidents and crimes (Fig 2: Google Trends, 2017; O’Keefe, 2021). The sudden yet significant 11.36% increase in reported crimes from 14,532 in 2017 to 16,186 in 2018 may be partially explained by the influence of social movements. It is possible that this upward trend reflects an increase in reporting rather than an actual increase in the occurrences of crimes (Georgallis, 2017). Understanding the dynamics behind reporting rates is crucial, as it provides valuable insights into the victimization process and avoids misrepresenting the situation through statistical means (Bolton, 2010).

Dark figure

For a crime to have taken place, it must first be recorded by the PSNI. There should be a perpetrator as well as a victim. A new category type of victim emerges from the dark figure called survivors.Survivors are individuals who may be victims of a crime, however, will be missing from these statistics due to the crime not being recorded or the criminal justice system (CJS) failing to reach a prosecution. The graph above displays the number of crimes as published within official statistics. However, official statistics are likely to fall short of the actual total number of crimes committed. A survivor is a recognized definition within society that can aid researchers in categorizing and understanding a type of victim that these statistics do not include (Aplin, 2019). A comparative analysis of victim incident reports, as well as PSNI crime reports can assist researchers with a firmer understanding of the dark figure (Buil-Gil et al., 2021).

The scope to formulate preventive measures against domestic abuse through purely quantitative data is argued to be limited at best (Lundy, 1996). Researchers continue to theorize as to why an individual may commit domestic abuse (Roberts et.al., 2010). Law and policy reform has proven to be effective in combating domestic abuse by adopting a comprehensive approach that integrates both quantitative and qualitative methods. This combined approach has enabled policymakers to achieve efficient and significant outcomes in addressing domestic abuse (Seymour, 2012; Reid, 2021).

Influences from a cultural perspective

Although the graph above does not capture the intersectionality of domestic violence, it is important to recognize the concept of intersectionality and its relevance to understanding the issue. Intersectionality, as coined by Crenshaw (1989), refers to the interconnected nature of social identities, such as, race, gender, sexuality and class, and how they intersect to shape an individual’s experiences and vulnerabilities to different forms of oppression and discrimination.

Within the context of domestic violence, intersectionality helps us understand how various social factors and identities interact to create unique experiences and challenges for different individuals. This includes considering and investigating the intersection of domestic violence and other forms of oppression, such as the historical involvement of child soldiers, or children witnessing historical violence within Northern Ireland.

Child soldiers should not be ignored as a historical issue within Northern Ireland, as their experiences during ‘The Troubles’ may have contributed to their involvement as both victims and potential perpetrators of domestic violence (Hamill, 2018). By analyzing this issue through an intersectional lens, an examination of the complexities and interconnectedness of the various factors that contribute to domestic violence there is the ability to move far beyond simplistic explanations based solely on statistics and that of an ethnocentric perspective (Strega et al., 2008, UNICEF, 2018; Wessells, 2009; Wessells, 2016).

Furthermore, it is worth nothing that research has indicated a direct link between post-deployment experiences in war zones and domestic violence among members of the United States army (Newby et al., 2005). This highlights the significance of considering the broader intersectionality of armed conflict exposure and its potential impact on the perpetration of domestic violence that is not limited to Northern Ireland.

Conclusion

Law changes and international social movements have been shown to have an impact both on the definition of domestic abuse as well as society’s perception of it. How researchers and policymakers respond to this is crucial (Stover, 2005). There is a direct correlation between crime statistics and how society perceives abuse which impacts policies and how future preventive laws are shaped.

The modern legal and social definition of domestic abuse within Northern Ireland (NI) since 2021 now includes methods of abuse, such as weaponized incompetence, gaslighting, manipulation and coercive control (Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland), 2021). However, this graph, as well as historical statistics, do not display this (Rumblelow, 2021). In observing a crime trend and how it is recorded and presented to researchers and policymakers, statistics can act as a tool through which domestic abuse can be challenged.

It is important to understand how the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) and PSNI work together in publishing findings. However, due to limitations they may find it hard to compile a complete tally of total crimes. Charities and confidants of victims, along with the Northern Ireland Victim and Witness Survey (NIVAWS), can further assist future statistical data and research.

References:

Álvarez Berastegi. A., & Hearty. K., (2019). “A context-based model for framing political victimhood: Experiences from Northern Ireland and the Basque Country.” International Review of Victimology, 25(1), pp. 19–36.

Aplin, R. (2019). “The Grey Figure of Crime: If It Isn’t Crimed, It Hasn’t Happened”, Policing UK Honour-Based Abuse Crime. York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bolton, P. (2010) “How to spot spin and inappropriate use of statistics”, Parliament UK. UK Government. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04446/SN04446.pdf (Accessed: November 1, 2022).

Buil-Gil, D., Medina, J. & Shlomo, N. (2021) “Measuring the dark figure of crime in geographic areas: Small area estimation from the Crime Survey for England and Wales”, British Journal of Criminology, 61(2), pp. 364–388.

Carter, B. (1993). “Child Sexual Abuse: Impact on Mothers.” Affilia, 8(1), pp. 72–90

Crenshaw, K. (1989) “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8.

Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021 (c.2) sections 1(2)(b)(ii) and 3(1). Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/nia/2021/2/contents (Accessed: November 2, 2022).

Douglas, H. (2015) “Do we need specific domestic violence offence?”. Melbourne University Law Review, 39(2), Pp. 434-471.

Georgallis, P. (2017) “The Link Between Social Movements and Corporate Social Initiatives: Toward a Multi-level Theory”. Journal of Business Ethics, 142 pp. 735–751.

Google (tran.) (2022) Search trend of #metoo within the UK. Available at: https://trends.google.com/ (Accessed: November 1, 2022).

Hamill, H. (2018). “The Hoods: Crime and Punishment in Belfast.”. Princeton University Press.

Hicks, S., Tinkler, L. & Allin, P. (2013) “Measuring Subjective Well-Being and its Potential Role in Policy: Perspectives from the UK Office for National Statistics”. Social Indicators Research, 114, p. 73–86.

Icheku, V., & Graham, L. (2017). “What Social Impact Does Exposure to Domestic Violence Have on Adolescent Males? A Systemic Review of Literature”. Journal of Women’s Health Care, 6(5)

Kero, K. M., Puuronen, A.H, Nyqvist, L & Langen, V.L(2020) “Usability of two brief questions as a screening tool for domestic violence and effect of #MeToo on prevalence of self-reported violence.” European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology vol. 255, pp. 92-97.

Krane, J. (2003) “What’s mother got to do with it?: Protecting children from sexual abuse.” Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Kukreja, P., & Pandey, J. (2023). “Workplace gaslighting: Conceptualization, development, and validation of a scale.” Frontiers in Psychology, 14. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1099485 (Accessed: June 2, 2023).

Lundy, P. (1996). “Limitations of quantitative research in the study of structural adjustment.” Social Science & Medicine, 42(3), pp.313-324.

McGonagle, S. (2022) “Police receive over 100 reports a month of coercive control since new legislation”. The Irish News. Available at: https://www.irishnews.com/news/northernirelandnews/2022/10/04/news/police_receive_over_100_reports_a_month_of_coercive_control_since_new_legislation-2848012/ (Accessed: October 23, 2022).

McQuigg, J. A. R, (2021) “Northern Ireland’s New Offence of Domestic Abuse”, Statute Law Review, 44(1), Pp. 1-19.

Newby, H. J., Ursano, J. R., McCarroll, E. J., Liu, X., Fullerton S. C., Norwood, E. A. (2005). “Postdeployment Domestic Violence by U.S. Army Soldiers”, Military Medicine, 170(8), Pp. 643-647.

NISRA. (2020) “Domestic Abuse Statistics”, Crimes with a domestic abuse motivation (NISRA). Available at: https://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk/public/PivotGrid.aspx?ds=10182&lh=42&yn=2005-2019&sk=131&sn=Crime+and+Justice&yearfilter= (Accessed: November 2, 2022).

Northern Ireland Government (2020) “Victim and witness research”. Justice NI: Belfast. Available at: https://www.justice-ni.gov.uk/topics/victim-and-witness-research (Accessed: November 2, 2022).

Offences Against the Person Act 1861. UK Government. London: The Stationery Office. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/24-25/100/contents (Accessed: October 21, 2022).

Office for National Statistics. (2017). Domestic abuse in England and Wales: Year ending March 2017. Available at: Https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/domesticabuseinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2017#coercive-and-controlling-behaviour (Accessed: June 2, 2023)

O’Keefe, M.H. (2021) “The Impact of the Me Too Movement’s Journalism,” Yale Journal. Available at: https://www.yalejournal.org/publications/the-impact-of-the-me-too-movements-journalism (Accessed: November 1, 2022).

PSNI, NIRSA. (2021) Trends in Domestic Abuse Incidents and Crimes Recorded by the Police in Northern Ireland, Police Service of Northern Ireland, 2004/05 to 2020/21. Available at: https://www.psni.police.uk/sites/default/files/2022-08/domestic-abuse-incidents-and-crimes-in-northern-ireland-2004-05-to-2020-21.pdf (Accessed: 24 October, 2022).

Reid, K. (2022) “PSNI receive more than 100 reports of coercive control a month following new laws”. Belfast Telegraph. Available at: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/psni-receive-more-than-100-reports-of-coercive-control-a-month-following-new-laws-42035393.html (Accessed: November 1, 2022).

Renneville, M. (2007) Gabriel Tarde (1843-1904). In: Clark, D. S. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Law and Society American and Global Perspectives.Willamette University, USA: Sage Publications.

Roberts, A. L., Gilman, S. E., Fitzmaurice, G., Decker, M. R., & Koenen, K. C. (2010) “Witness of intimate partner violence in childhood and perpetration of intimate partner violence in adulthood”. Epidemiology, 21(6), Pp. 809–818.

Roberts, A.L., McLaughlin, K.A., Conron, K.J., & Koenen, K.C. (2011). Adulthood Stressors, History of Childhood Adversity, and Risk of Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(2), Pp. 128-138. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.016

Rumbelow, H. (2021) “Weaponised incompetence” – it’s the new battle of the sexes. The Times, 06/10/2021. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/weaponised-incompetence-its-the-new-battle-of-the-sexes-kds7bc553 (Accessed: November 1, 2022).

Serious Crime Act 2015, c. 9. (2015). UK Government: Great Britain. London: The Stationery Office. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/9/contents/enacted (Accessed: June 2, 2023)

Seymour, J. (2012). “Combined qualitative and quantitative research designs.” Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 6(4), Pp. 514-524.

Siegel, L. J. (2000) Criminology. 7th ed. Belmont, California: Wadsworth.

Stamenković, D. (2021). “Protection against domestic violence in the meaning of the family Law and the Law on social protection”. Pravo – teorija i praksa, 4(38), Pp. 175-188. ttps://doi.org/10.5937/ptp2104175s (Accessed: June 2, 2023)

Strega, S., Fleet, C., Brown, L., Dominelli, L., Callahan, M., & Walmsley, C. (2008). “Connecting father absence and mother blame in child welfare policies and practice”. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(7), Pp. 705–716.

Stover, C. S. (2005). “Domestic Violence Research: What Have We Learned and Where Do We Go From Here?” Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(4), Pp. 448–454.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2018). Child Soldiers. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-violence/explore-issues/child-soldiers (Accessed: June 2, 2023)

Wessells, M. G. (2009). “Child soldiers: From violence to protection”. Harvard University Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1dv0trf (Accessed May 28, 2023)

Wessells, M. G. (2016). “Children and armed conflict: Introduction and overview”. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 22(3), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000176

Appendix