Public Apologies on Weibo: A Study of Language, Culture, and Platform Dynamics by Kong Qiuyu

MSc TESOL and Applied Linguistics

The Search Story

Introduction to the topic

As Brooks observes, we live in the “age of apology” (Brooks, 1999, p. 3), and the only thing that has changed significantly over the years is the human ability to say “I am sorry” (Brooks, 1999). Before the advent of the Internet, people expressed their apologies verbally and privately. However, with the development of the Internet and Weibo becoming one of the most influential social media platforms for news exchange in China (Zhang, 2020), more and more people choose to make public apologies on Weibo. Public apologies are also critical to social interplay and are a mechanism for addressing grievances, restoring trust, and rebuilding reputations (Austin, 1962; Goffman, 1982).

In China, public apologies typically occur on Weibo. Similar apologies are made through various platforms and methods in other countries and cultures. For example, celebrities or companies in the U.S. and the U.K. often apologize on X or Instagram (Cerulo and Ruane, 2014; Jegede, 2024). And in Japan and South Korea, it’s still common to hold press conferences to apologize, usually accompanied by a deep bow or handwritten letter (Hatfield and Hahn, 2011; Jaohari and Ariestafuri, 2020). These examples illustrate that similar practices exist worldwide out of a need to save face, rebuild credibility, and maintain public order, despite the different social media platforms used. They also demonstrate the intertwining of technological means and cultural values in shaping how public apologies are made everywhere.

Hook and Personal Curiosity

According to Weibo’s financial report (Weibo Corporation, 2024), Weibo has 587 million monthly active users and 257 million daily active users as of September 2024. Consequently, I was intrigued by observing the large user base of Weibo and the growing number of cases of public apologies made on Weibo. Public apologies on Weibo come from various groups, including celebrities, corporations, governments, and individuals. At the same time, these groups will get different results from using Weibo to apologize. Some groups respond quickly to wrongdoing, apologize promptly, and offer appropriate remedies, and they will be recognized and appreciated by the mass community. In contrast, under pressure from public opinion, other groups choose to make excuses or exaggerate the heat to maintain their commercial value; they will be massively mocked and belittled. These aroused my keen interest: What are the effects of public apologies on Weibo? How do language choices, cultural values, and platform-specific features shape these apologies? Do apologies come in a way that elicits public understanding and forgiveness?

What I Knew Before Starting

Before I began this paper, I had discovered the impact of apology as a linguistic characteristic in the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom and that an apology is taking duty for an offense and expressing remorse for the offense committed (Fraser, 1981); however, I knew little or not approximately the idea of public apologies. Moreover, a way to integrate public apologies with Weibo, a platform specializing in disseminating cutting-edge activities and interaction, aroused my interest. Guided by Macrorie (1988), I-Search paper is a qualitative methodology prioritizing the researcher’s reflexive journey through three phases: pre-existing knowledge documentation (What I Knew), transparent process narration (The Search), and critical synthesis (What I Learned), I aim to systematically discover the linguistic features, cultural effects, and technological dynamics of public apologies on Weibo and their effectiveness in assembling target market expectations.

The Research Process

Based on my interests and my research topic, I carried out my research in an organized manner. First, I extensively reviewed the Chinese and foreign literature on public apologies to support my theoretical framework. Among other things, I focused on analysing and studying Limberg’s (2016) definition of apology, the strategies he articulated for apologizing, and the differences in the implementation of apologies; I explored Austin’s (1962) Speech Act theory, Goffman’s (1982) Face Theory, and Xu and Li (2020), scholars from China, analysing the Chinese celebrities’ public apologies on Weibo. These literatures gave me in-depth insights into apologizing as a linguistic feature and social effect. Next, I collected and analysed several examples of typical Weibo apologies, a process that once again inspired me to further my understanding of the topic.

In the process of writing my I-search paper, I searched and organized the articles I needed, referenced them in Canvas Core Reading, Google Scholar, Queen’s University of Belfast’s online library, and China Knowledge Network, and downloaded them to my computer for my ongoing study; I also organized them in Zotero to make them easier to cite in my paper.

Literature Review

A public apology is often considered a performative speech act that acknowledges mistakes and restores social relationships (Austin, 1962; Goffman, 1982). In other words, the role an apology plays in a given situation is as important as its content. The notion of face work, developed by Goffman (1982), emphasizes that apologizing is a means of coping with a reputational crisis by negotiating self-image in a public setting. While these classic theories are valuable for understanding the basic mechanisms of apologizing, they do not fully explain the phenomenon in the digital age. Today’s apologies are influenced not only by the rules of interpersonal relationships but also by the characteristics of social media platforms and changing cultural logics.

The rise of social media has revolutionized the way people apologize, making it more public, strategic, and even performative. According to Page (2014), apologies on X, particularly those from brands or celebrities, are frequently influenced by platform limitations such as word limits, fragmented audiences, and algorithm-driven communication mechanisms. Boyd (2010) and Marwick and Boyd (2011) refer to such platforms as networked publics, where apologists’ identities and responsibilities are constantly renegotiated before a dispersed and elusive audience. However, most of these studies focus on Western contexts. To put it differently, they don’t thoroughly consider environments like China’s Weibo. In China, apologies on Weibo have been influenced by viral dissemination, high levels of user interaction, and the platform’s functional design (Sullivan, 2014; Xu and Li, 2020). However, they have also been profoundly affected by state regulation, collectivist culture, and a dominant ideology emphasizing moral rectitude.

Public Apologies by Celebrities

On China’s Weibo platform, celebrity apologies tend to be high-stakes performances. They usually combine emotional language with symbolic gestures. According to Xu and Li (2020), celebrities in China often apologize by using emotional words such as shame or by writing handwritten letters that subtly express mistakes. These practices actually reflect collectivist culture and the need to save face. This is also consistent with Kadar, Ning, and Ran’s (2018) and Maddux et al.’s (2011) argument that apologizing in East Asian popular culture is not only an expression of remorse but also a ritual that demonstrates respect for the public. However, this kind of apology is not always effective. Ancarno (2015) points out that if an apology seems insincere, comes too late, or gives the impression that the apologizer is shirking responsibility, the public may strongly resent it. Furthermore, Zhang (2020) argues that if an apology is overly performative, it can easily be imitated and mocked by netizens, failing to achieve the desired effect.

Corporate Apologies and Strategic Image Repair

In the context of Weibo, enterprises’ public apologies are often reduced to strategic performances. While it appears to be a crisis response, it is essentially a means of controlling public opinion. Although Benoit’s (1995) image repair theory shows how corporations can reduce liability through apologies, it overlooks that apologies in the digital age are subject to politics and emotions. In China, apologies are no longer just a way of responding to mistakes; they are a ritual demonstrating loyalty and obedience to a particular ideology. According to Zheng and Wu (2021), the public increasingly judges corporate apologies based on political correctness and emotional performances rather than on a factual basis and responsibility.

In this situation, companies are more focused on saying sorry quickly and using the right words than taking responsibility or thinking about the bigger problems. Consequently, the apology loses its proper social repair function and becomes a mere attempt to conform to public opinion.

Government Apologies and Institutional Legitimacy

Government apologies are more closely associated with authority, responsibility, and national image than are celebrity or corporate apologies. However, such apologies are often not made to accept responsibility, but rather to maintain institutional authority. Li, Ni and Wang (2021) points out that the Chinese government frequently uses vague, technical language in its apologies to downplay the problem and avoid blame. These statements seem to be responses to the public but are actually performances of we will improve, intended to demonstrate rational governance rather than admit fault. This strategic ambiguity is no accident. Instead, it exemplifies Cels’s (2015) claim that discourse is used to create the illusion of responsiveness while maintaining the legitimacy of the bureaucracy.

Apologies become tools for calming emotions rather than processes for initiating accountability and reflection. This practice diminishes the ethical significance of apologies, transforming public communication into a discursive operation that maintains a responsive posture while avoiding real accountability.

Ordinary Users and Relational Repair

On Weibo, celebrities and corporations publicly apologize, and ordinary users do as well, often because of emotional disputes, online conflicts, or public pressure. Though not much academic attention has been given to these kinds of apologies, they are very telling: the platform is turning emotional expression into a prescribed performance. Then, Ahn and Lin (2019) and Xu and Li (2020) found that many users mimicked celebrity apologies, such as handwritten letters and kneeling videos. This is not a coincidence but a result of the platform’s culture instilling performance templates.

As Ho (2007) points out, apologizing serves as a social signal during a crisis of trust. It can help restore damaged relationships and trust. But why does it have to be public? Why must private emotions be displayed publicly? Ultimately, the platform encourages visibility and promotes performance over genuine emotional expression. Sincerity becomes tainted, apologies become performances expected by the public, and individuals lose their freedom to speak.

Platform Dynamics and Cultural Mediation

The emergence of social platforms like Weibo has broadened the types and scope of apologies. At the same time, the interactive nature of Weibo and its large user base have increased the speed of disseminating and discussing apologies. Apologizing on social media is becoming increasingly crucial for celebrities, corporations, governments, and individuals’ image management (Xu and Li, 2020). However, this also makes public image crisis management complex and challenging to control.

In addition, like other social media platforms, Weibo has its structural limitations; for example, the Weibo platform is also limited by the number of words, images, and other factors. People usually use concise language or simple photos to express their apologies (Van Dijck, 2013). However, in recent years, Weibo has adhered to meeting users’ needs, but it has also added more and more features to optimize the platform.

The Search Results

Based on my searches, I have concluded that a public apology is essentially based on the following steps.

- Acknowledgement of fault

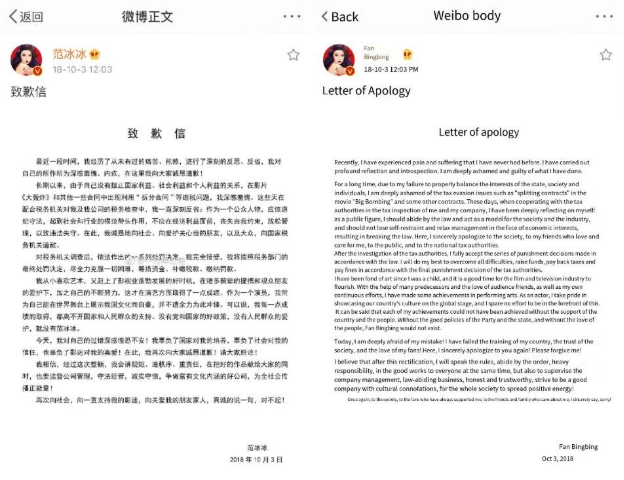

A public apology starts with acknowledging your faults. Ms. Fan, a famous Chinese actress, was reportedly fined for tax evasion in 2018. In her apology Weibo post, she said: “I am humiliated and guilty of what I have done, and here I sincerely apologize to everyone!” as shown in Appendix 1, Item 1. She begins by admitting her mistake to gain sympathy and repair her image (Benoit, 1995). This contrasts with Austin’s (1962) view of the apology as a performative speech to address grievances.

2. Explain reasons

The second step in a public apology is usually an explanation of the reason for the apology.

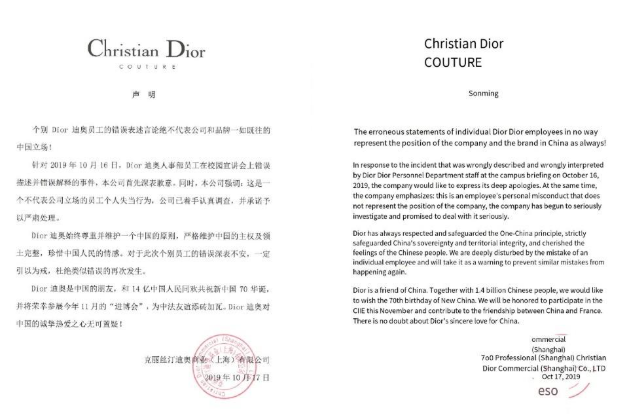

On October 16, 2019, Dior sparked a public outcry when they displayed a map of China that did not include Taiwan during a presentation at a Chinese university. Forced by the pressure of public opinion and brand image issues, Dior issued a Weibo public apology; in the Weibo text, Dior explains the reason for this: “This is an employee’s misconduct that does not represent the position of the company, the company has begun to investigate seriously and promised to deal with it seriously.” (See Appendix 1, Item 2). Dior targeted its employees for this incident, attempting to preserve Dior’s collective interests at the expense of the individual. This aligns with Goffman’s (1982) point that a public apology would help maintain group harmony and social order. This reflects a collectivist mindset, which aims to repair individual relationships and restore group harmony.

3. Proposing solutions

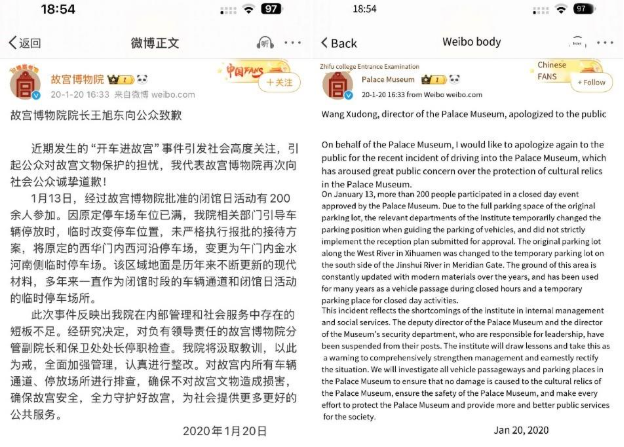

The third step in a public apology is to propose a solution. On January 17, 2020, Weibo user “Lu Xiaobao LL” posted a photo showing her driving a black Mercedes-Benz SUV into the Taihemen Square of the Palace Museum in Beijing. Motorized vehicles have been banned from the Palace Museum since 2013, sparking a public outcry.

Later that day, the Palace Museum responded via its official Weibo, confirming the incident was actual and sincerely apologizing to the public. The Palace Museum mentioned in a Weibo post: “The deputy director of the Palace Museum and the director of the Museum’s security department, who are responsible for leadership, have been suspended from their posts.” Refer to Appendix 1, Item 3 for a screenshot. This incident resulted in the punishment of the person in charge of the Forbidden City and was resolved. Most Internet users accepted the apology because the sentence was intense, and the Palace responded quickly and apologized sincerely without damaging cultural relics. This is consistent with Clyde Ancarno’s (2015) point that a successful apology takes responsibility.

4. Obsecrate excuse

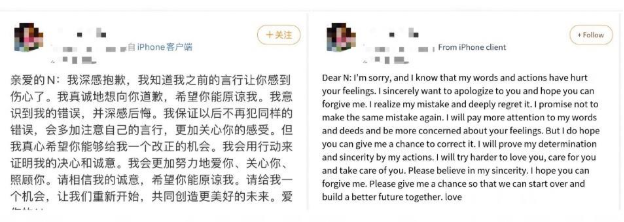

Asking for forgiveness is often used as the final step in a public apology. In addition to celebrities, corporations, and governments that use Weibo to apologize publicly, individual users also use Weibo to make public apologies. Since it concerns the user’s privacy, I will not repeat the cause of the incident here and only briefly list some of the contents of his Weibo: “I will prove my determination and sincerity by my actions. I will try harder to love, care for, and care for you. Please believe in my sincerity. I hope you can forgive me.” (Appendix 1, Item 4) This user displays sincere words to ask their loved one to forgive them and try to save the relationship. At the same time, due to the Weibo platform’s fast deliverability and large user base (Sullivan, 2014), it is not limited only to public apologies. Weibo also affects the speed of its reception and delivery. Meanwhile, due to the limitations of the Weibo platform (Benoit, 1995), in earlier years, Weibo only had a 140-character limit, so many people used handwritten letters, apology videos, etc., to post their apologies on Weibo to show the sincerity of their apology. Although it is now possible to post 1,800-word Weibo posts, people are still using all sorts of novel ways to generate heat and expand the reach of their public apologies.

In summary, Weibo’s public apologies combine linguistic strategies, cultural norms, and platform features to resonate with audiences. The structure and expression of these apologies—acknowledgments, explanations, corrective measures, and requests for forgiveness—play a crucial role in their effectiveness. In addition, Weibo’s digital environment amplifies these apologies, ensuring rapid dissemination and extensive influence.

Search Reflections

Insights Gained

By analysing and searching for public apologies on Weibo, I have learned that effective apologies on Weibo must consider linguistic strategies (Limberg, 2016), the limitations of the Weibo platform and its specific dynamics (Zhanghong and Yanan, 2020), and complexities such as China’s cultural norms of face-saving (Goffman, 1982). In addition, the four steps of a public apology also have a significant impact. The interplay of these factors determines whether an apology will resonate with the listener or backfire.

Challenges and Adaptations

I also faced many challenges in conducting this search. At first, identifying representative cases from the vast number of apology-related posts on Weibo was challenging. However, combining the theoretical framework of public apologies with real-life examples gradually helped me clarify my thoughts and draw meaningful conclusions. Secondly, finding the literature that I wanted to correspond to my research topic was also one of the challenges. However, Queen’s University’s colossal library and well-developed Internet helped me immensely to have enough theoretical support for this search and to complete it successfully.

Broader Implications

Through this search, I feel that the definition of a public apology has expanded and highlights the ever-evolving nature of online communication in the digital age. A public apology is no longer just an expression of regret (Limberg, 2016); it can be a performance tailored to the needs of a multifaceted, diverse, and interactive audience. At the same time, although the Weibo platform has its limitations, it is strong enough to become a platform for people to apologize, save their image, and communicate and interact with each other. Weibo’s digital environment amplifies these apologies, ensuring rapid delivery and broad reach.

References List

Ancarno, C. (2015) ‘When Are Public Apologies “Successful”? Focus on British and French Apology Press Uptakes’, Journal of Pragmatics, 84, pp. 139–153. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.04.015.

Austin, J.L. (1962) How to Do Things with Words. Oxford University Press.

Benoit, W.L. (1995) Accounts, Excuses, and Apologies: A Theory of Image Restoration Strategies. State University of New York Press.

Brooks, R.L. (1999) When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy Over Apologies and Reparations for Human Injustice. NYU Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg0xt (Accessed: 10 December 2024).

Goffman, E. (1982) Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior. New York: Pantheon Books. Available at: http://archive.org/details/interactionritua0000goff_r9e2 (Accessed: 10 December 2024).

Limberg, H. (2016) ‘Teaching How to Apologize: EFL Textbooks and Pragmatic Input’, Language Teaching Research, 20(6), pp. 700–718.

Macrorie, K. (1988) The I-Search Paper-Revised Edition of ‘Searching Writing.’ Heinemann Educational Books Inc.

Sullivan, J. (2014) ‘China’s Weibo: Is Faster Different?’, New media & society, 16(1), pp. 24–37. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812472966.

Van Dijck, J. (2013) The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media Oxford Academic. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/book/9914 (Accessed: 12 December 2024).

Weibo Corporation W.C. (2024) ‘Weibo Financial Report: Q3 2024 Total Revenue Reaches 3.294 billion CNY’, 20 November. Available at: //www.199it.com/archives/1727712.html (Accessed: 23 February 2025).

Yang, W. X. (2017) A Study of the Image Restoration Discourse on Micro-blog Apologies Posted by Entertainment Celebrities. Fujian Normal University, China

Zhang, S.I. (2020) ‘China’s Social Media Platforms: Weibo’, in Media and Conflict in the Social Media Era in China. Singapore: Springer, pp. 21–40. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7635-5_2.

Zhanghong, X. and Yanan, L. (2020) ‘A Pragmatic Study of Apologies Posted on Weibo by Chinese Celebrities’, International Journal of Literature and Arts, 8(2), p. 52. Available at: https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijla.20200802.14.

Appendices

Appendix 1-Visual Examples of Public Apologies on Weibo

- Fan Bingbing’s Apology Post (October 3, 2018)

Type: Celebrity Apology

Context: Tax evasion scandal

Note: This post includes direct acknowledgment of wrongdoing and expressions of guilt. It demonstrates the use of emotional language and indirect face-saving typical in celebrity apologies on Weibo.

- Dior’s Apology Post (October 16, 2019)

Type: Corporate Apology

Context: Territorial integrity controversy (China map without Taiwan)

Note: This apology demonstrates a strategic shift of responsibility to an individual employee, in line with Benoit’s (1995) theory of image restoration.

- Palace Museum’s Apology Post (January 17, 2020)

Type: Institutional Apology

Context: Vehicle entry into a restricted cultural site

Note: The apology focuses on swift administrative action and institutional accountability.

- Anonymous Weibo User Apology (Date unspecified)

Type: Individual Apology

Context: Romantic conflict

Note: The apology reflects a highly emotional and personal tone, representing ordinary users navigating relational repair in public.