Briefing Paper: Drugs Use in English & Welsh Prisons

By Caoimhe O’Reilly

Year 3

Criminology and Sociology Undergraduate Student

Introduction

Research as early as 1997 has highlighted how drug addiction and the consequences thereof are causes for significant concerns for the welfare of those in prison, as well as members of the wider community (Cope, 2003; Edgar & O’Donnell, 1998; Keene, 1997). Such adverse consequences continue in today’s prisons, highlighting the shortcomings of previous and current attempts to curb this issue (Vaccaro et al, 2022; Haviv & Hasisi, 2019). Effects of prisoner drug use include: an enhanced hostile prison environment; violence; victimisation; self-harm; suicide; and countless health issues (Vaccaro et al, 2022; Michalski, 2017; Ralphs et al, 2017; Mitchell et al, 2009; Nutt et al, 2007; Dillon, 2001). Whilst the government currently have policies in place to deal with drug use, its levels are only increasing, and therefore it is necessary to update and improve these, as will be discussed in later sections. This briefing paper will first examine the extent and nature of the problem, provide a theoretical base for understanding this issue, investigate current policies that are in place, and finally provide policy makers with evidence-based recommendations for policy reform.

Defining the Extent and Nature of the Problem

New psychoactive substances (NPS) are seen to make up the largest group of drugs in prison (Norman, 2022; Jewkes et al, 2016). NPS are synthetic drugs, classed as either stimulants, cannabinoids, hallucinogens or depressants (Shafi et al, 2020). Synthetic cannabinoids (such as spice) are the most popular type of NPS used in English and Welsh prisons (Norman, 2022), and despite official statistics describing this as cannabis, it is evident that spice is growing in popularity (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2022; Duke, 2020; Ralphs et al, 2017; HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2015). Both those in prison and prison staff have asserted their belief that between 60%-90% of prisoners have experimented with NPS (Norman, 2022; Ralphs et al, 2017), and those in prison have reported spice being the “new drug of choice” (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2015: 35).

However, this trend is otherwise underrepresented in official statistics due to the difficulty in detecting spice’s use in prisoners through mandatory drug testing (MDT), and its stigmatised nature and increased consequences means self-reporting is unlikely (Duke, 2020; Kolind & Duke, 2016). NPS are more difficult to detect due to a lack of biochemical tests (known as immunoassays) available, and more traditional tests being unable to detect them due to their ever-changing chemical structure (Costantino et al, 2019). With the implementation of MDT, there has been a shift away from the use of more traditional drugs such as cannabis (HM Prison & Probation Service, 2019; Nutt, 2019; Tompkins, 2016). This is due to the higher likelihood of cannabis users being caught, as it stays in the human system for two weeks, in comparison to spice or other NPS, which are only detectable for approximately two days (Norman, 2022; Vaccaro et al, 2022; Ralphs et al, 2017). This makes NPS more appealing, convenient, and less risky for users, therefore increasing demand for them, and supply of them (Norman, 2022; Ralphs et al, 2017).

Many of those entering prison bring problems with drug abuse into prison. Research asserts that drug use in prison often reflects that of the community (Norman, 2022; Tompkins, 2016; HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2015). However, it is evident that those who use drugs before incarceration primarily use cocaine, cannabis or heroin, and upon entry into prison this then switches to spice and cannabis (HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2015). Most only first tried NPS in prison due to its easy access and higher potency (Norman, 2022; Vaccaro et al, 2022; Ralphs et al, 2017; HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2015).

Additionally, while the frequency of drug use may decrease in prison in comparison to the community, factors including poor availability and excessive cost of the drugs may result in more dangerous drug use with consequent enhanced risk of overdose and infection (such as HIV) (Hendrich et al, 2011; Dillon, 2001). In other words, lack of availability of drugs often means withdrawal symptoms have been experienced in the time that no drugs were available, and therefore stronger doses are used in order to return the drug user back to a normal state (Hendrich et al, 2011; Dillon, 2001). This greatly increases the risk of overdose and possible death from drug use, highlighting the severe adverse consequences of drug addiction (Norman, 2022; Hendrich et al, 2011).

The adverse consequences of drug addiction, combined with the actual health complications (risk of HIV, infections, overdose, withdrawal symptoms, psychological issues, impaired cardiac and respiratory functions), highlight the need for robust policies to be implemented so that prisons become a safer environment (Mitchell et al, 2009; Nutt et al, 2007). Violent behaviour in the prison setting has been connected to general substance abuse, but especially NPS (Mason et al, 2022; Rocheleau, 2015). Additionally, more vulnerable populations in prison can be targeted by drug users and dealers to smuggle drugs in, be bullied out of their medication, or be given free drugs to get them addicted (Page, 2017; Tompkins, 2016; Watson, 2016). Finally, Opitz-Welke et al (2016) discuss how suicide and self-harm are other risk factors which are present in a high number of those in prison with a drug addiction. As such, it could be asserted that dealing with drug abuse is likely to reduce the rates of suicide and self-harm among inmates. One method of dealing with drug use in prison is limiting the routes by which they make their ways into the establishment, through smuggling routes.

Smuggling

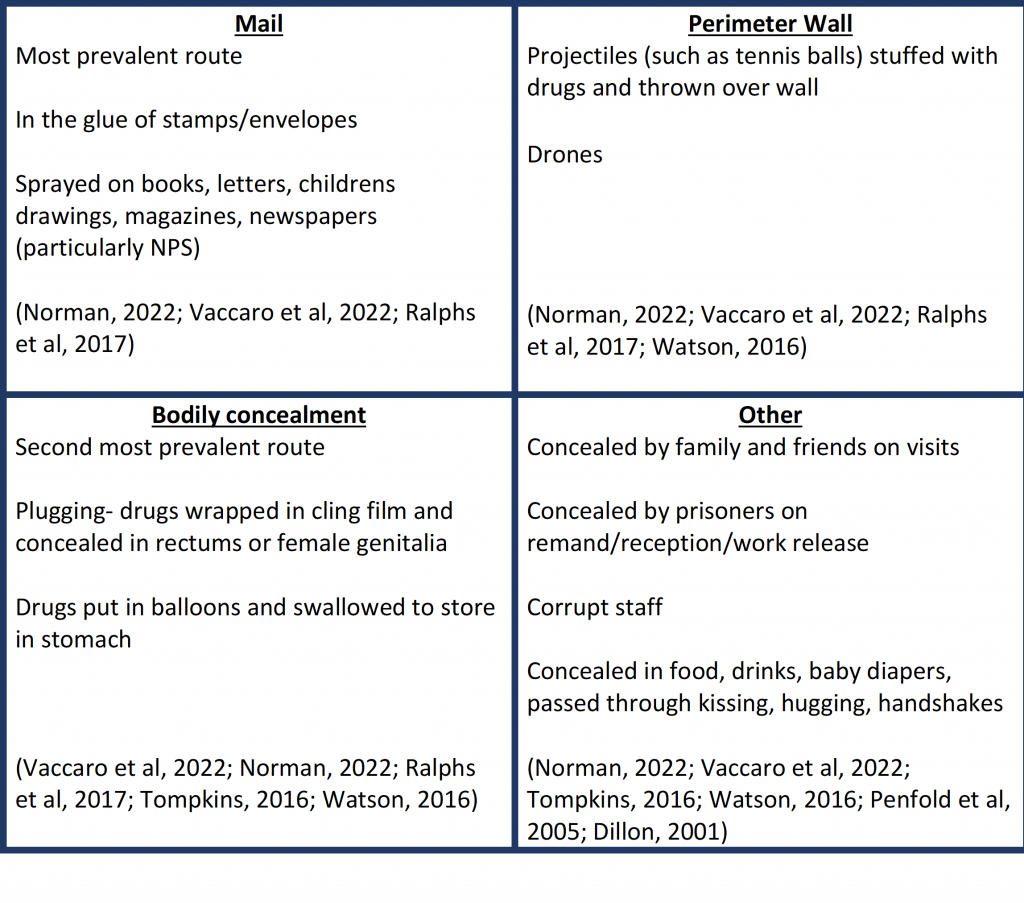

To tackle the problem of drugs in prison, one needs to understand the different ways in which the drugs themselves are smuggled into the prison. The primary routes used are explained below:

Individuals smuggle drugs into prison for a myriad of reasons. The first, and primary reason, is for lucrative payment opportunities (Norman, 2022). Both prison staff and prisoners themselves are involved in smuggling, due to the much higher value of drugs in prison than in general society (Norman, 2022). Additionally, individuals can be coerced or threatened by those in prison into smuggling drugs into the establishment (Colvin, 2007). Other theories can similarly be used in order to understand the need for drugs and drug smuggling for those in prison, as will be discussed in the following section.

Theoretical Approaches to Understand the Problem

Drug use in prison can be examined through the theoretical lens of the mixed model approach, which encompasses both the importation and deprivation models. The importation model focuses on how one’s own personal background (ie: trauma, previous experiences) can influence their behaviours and coping (Sykes, 1958). The deprivation model highlights how a depraved environment, such as a prison, can aggravate individuals, once again resulting in unhealthy coping mechanisms (Sykes, 1958). The mixed model combines both of these and focuses on how one’s own personal history and experiences can be exacerbated by the difficulties of the prison environment to influence behaviour and coping (Abderhalden, 2022; DeLisi et al, 2011; Hochstetler & DeLisi, 2005; Cao et al, 1997; Sykes, 1958). The majority of those entering prison have had problems with drug abuse prior to their incarceration, with opioid use disorders being present in 61% of men and 69% of women on entry to prison (Norman, 2022; Komalasari et al, 2021; Ralphs et al, 2017; Mjaland, 2016; Dillon, 2001). Additionally, many prisoners have comorbid disorders, such as mental health and drug abuse (Linhorst et al, 2012; Sacks et al, 2007). When met with the difficulties of living in prison (ie: loss of freedom, goods, and services, forced celibacy, and living with other prisoners (Sykes, 1958)), these imported problems can lead to the development of unhealthy coping mechanisms (Ralphs et al, 2017; Kolind & Duke, 2016; Liebling & Maruna, 2011; Dillon, 2001). Drugs can be used in this regard to deal with prison life through escaping reality, alleviating stress, curing boredom, passing time quicker, and sleeping (Vaccaro et al, 2022; Ralphs et al, 2017).

The status model can also be used to investigate the use of drugs in prison (Kanato, 2008). This model shows how those in prison seize the opportunity to take drugs, because in doing so, they strengthen their status and position within the prison social hierarchy (Jewkes et al, 2016; McLaughlin & Muncie, 2001). Drug use can be used as a form of protest against the perceived injustice within the prison system, and this behaviour can earn the respect of fellow prisoners (Michalski, 2017; Mjaland, 2016). Certain research suggests that obtaining status is the primary reason why those in prison take drugs (Mjaland, 2016), and therefore one recommendation, which will be discussed further in later sections, is to create a better prison environment, so the need to gain status is not necessary. This would also aid in reducing the impact of the prison environment, ie: the deprivation model, on drug use, further reducing it and its impact on those in prison (Mjaland, 2016; Sykes, 1958). These theories are key in the development and implementation of government policies for tackling the drug epidemic in prisons (Abderhalden, 2022; DeLisi et al, 2011; Hochstetler & DeLisi, 2005). As such, it is necessary to investigate current policies in order to reveal where these policies are lacking in their theoretical base, and how they can be updated and improved.

Analysis of Current Practices

Currently, English and Welsh prisons are implementing a ten-year drug scheme published in 2021, focused on disrupting supply, shifting demand, and providing treatment and recovery programs (Holland et al, 2022). Searches of prisoners and visitors entering the prison, metal detectors, and drug dogs are the primary methods used to disrupt the supply of drugs in prison (HM Prison and Probation Service, 2019). However, it has been shown that such supply interventions are not particularly efficient at reducing drug use in UK prisons (Bacon & Spicer, 2022). Firstly, the drug market is skilled at adapting to adverse circumstances to stay alive, as evidenced in the structure of NPS being constantly altered to avoid detection (Norman, 2022). Secondly, English and Welsh prisons have certain restrictions on searches that can be conducted on prisoners due to the potential for physical and psychological trauma (Ralphs et al, 2017). This means that without the use of more advanced body scanners, up to £28,000 worth of drugs can be smuggled in by a single prisoner through the plugging method, as mentioned above (Norman, 2022). Thirdly, as previously stated, the chemical structure of NPS are constantly changed to bypass drug dogs and MDT, thus making these an inaccurate tool for measuring drug use (Vaccaro et al, 2022), which could subsequently affect policy-making and practice. Finally, this supply-side strategy fails to consider the violent effects of removing drugs from prison and fails to provide any legal alternative, such as tobacco or herbal cannabis that would curb these effects (Bacon & Spicer, 2022; Nutt, 2019; Dillon, 2001). Such alternative options have previously been rejected by policy makers, likely due to stigmatisation and reluctance to use drug-centered treatments (Komalasari et al, 2021; Nutt, 2019). This abrupt removal of drugs from prison, without any alternative, leaves those addicted with severe withdrawal symptoms, and often causes high tensions between prisoners, which can lead to violence (Komalasari et al, 2021; Bacon & Spicer, 2022).

On the demand side, English and Welsh prisons are currently attempting to reduce the demand for drugs in prison through more severe consequences for those caught, as well as providing those in prison with education on the effects of drug use to encourage deterrence (Holland et al, 2022; Watson, 2016). One could argue that punishments (such as losing certain privileges) could add to the deprivation that is already experienced by prisoners, and therefore increase their likelihood of coping through drug use (Ralphs et al, 2017; Kolind & Duke, 2016; Liebling & Maruna, 2011; Dillon, 2001). Alternatives to this method of deterrence are discussed in further sections.

Drug treatment programs in English and Welsh prisons are either pharmacologically or psychosocially informed. Pharmacological interventions include prescribing opioid agonist drugs such as methadone or buprenorphine to wean individuals off illicit drugs (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2022; Komalasari et al, 2021; Doyle et al, 2019; Kolind & Duke, 2016; Hendrich et al, 2011; Dillon, 2001). On the other hand, psychosocial treatments are more therapeutic interventions which focus on changing the cognitions of those with an addiction, for example through engagement in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Sondhi et al, 2020). Between 2022 and 2023, 80% of opiate abusers in English and Welsh prisons received pharmacological treatment, while 44% received both pharmacological and psychosocial treatments (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, 2022). This treatment lasts between 112-154 days (Page, 2017) in keeping with research recommendations that drug treatment should last between 90-150 days (Haviv & Hasisi, 2019; Linhorst et al, 2012). However, Komalasari et al (2021) show that the use of dual intervention strategies (pharmacological and psychosocial together) is more efficient at preventing relapse and recidivism than one of these strategies alone. They highlight how dual intervention services are efficient at reducing drug use, improving feelings of safety amongst staff and prisoners, and increasing participation in other prison programs, such as education and sports. Therefore, it is essential to make this treatment available to more who need it.

Lastly, there are also some drug-free wings in English and Welsh prisons, which are areas not separated from the rest of the prison, but where non-drug-using prisoners stay to decrease the potential for drug use (Page, 2017; Tompkins, 2016; Dillon, 2001). In these wings, there is more security, MDT, and narcotics anonymous meetings than in other standard areas of the prison (Page, 2017). Despite this increased security, drug dealers are more than capable of infiltrating, and providing these prisoners with free samples, to obtain continued sales (Page, 2017; Tompkins, 2016; Watson, 2016). This therefore provides them with a group of especially vulnerable people, all in the same place, that can be exploited (Tompkins, 2016). Therapeutic communities are one solution that could be implemented in the replacement of these wings. These are more isolated and closed off areas of the prison where those with drug addictions can go through treatment, separate from the rest of the prison (Doyle et al, 2019; Alsan, 2018; Mitchell et al, 2012). These differ from drug free wings in their implementation of effective treatment plan (both pharmacological and psychosocial), and their closed off nature, while drug free wings only ensure a lack of drug supply, not necessarily treatment (Doyle et al, 2019; Alsan, 2018, Tompkins, 2016). As such, it is necessary to upgrade current policies in order to effectively deal with drug use in prison, as will be discussed below.

Recommendations for Improvement

This paper recommends the upgrade from body searches and metal detectors to transmission X-ray machines in all English and Welsh prisons. This upgrade allows one to view if someone entering the prison has used the plugging method to smuggle contraband in body cavities, as mentioned above (Sinclair & Hertzog, 2017; Mehta & Smith-Bindman, 2011). Other body scanning technology is also available, such as the backscatter x-ray and the millimeter wave, however, these both simply generate an image of the body itself, not what is potentially concealed inside of it (Sinclaire & Hertzog, 2017; Mehta & Smith-Bindman, 2011). While these do come at a high cost, certain research argues that the time it saves staff from having to search for people saves money in the long run (Norman, 2022; Sinclair & Hertzog, 2017). Additionally, it spares the prisoners themselves from any risk of psychological trauma, as there is no need to undress to facilitate searching (Norman, 2022; Sinclair & Hertzog, 2017).

Furthermore, this paper recommends a switch from drug free wings to therapeutic communities (TC) in English and Welsh prisons. As aforementioned, TC’s are an area of the prison where drug-free prisoners live, separately from all other prisoners (Doyle et al, 2019; Alsan, 2018; Mitchell et al, 2012). Living with other drug-free prisoners provides peer support and a sense of community, therefore improving the prison environment and aiding recovery and rehabilitation (Alsan, 2018). Improving the prison environment would reduce the deprivations experienced by prisoners, and subsequently the need for drugs to be used as a coping mechanism (Ralphs et al, 2017; Kolind & Duke, 2016; Liebling & Maruna, 2011; Dillon, 2001; Sykes, 1958). Reducing such deprivations through increased support would reduce the need for unhealthy coping mechanisms, through drug use (Ralphs et al, 2017; Kolind & Duke, 2016).

This paper recommends that these TCs provide prisoners with CBT or similar psychosocial interventions and opioid agonist treatment (OAT) (Alsan, 2018; Azbel et al, 2017). OAT involves the use of transition drugs, such as methadone and buprenorphine for aiding individuals with an addiction in no longer being dependent on illicit drugs (Komalasari et al, 2021). This ensures reduced withdrawal symptoms and a decrease in relapse after release from prison (Komalasari et al, 2021).

CBT focuses on changing one’s cognitions surrounding their addiction, their emotions and the way they cope with these feelings and cognitions (Haviv & Hasisi, 2019; Davis et al, 2014). This involves counselling for past or current mental health issues, and the development of healthier coping mechanisms, so they no longer use drugs to fulfil this function (Doyle et al, 2019; Davis et al, 2014). This would clearly improve issues that prisoners import into the prison, therefore reducing the likelihood that prisoners will turn to drug use (Doyle et al, 2019; Davis et al, 2014). OAT involves the regular administration of opioid agonist drugs, such as methadone or buprenorphine to aid withdrawals from drugs, and gradually reduce prisoners’ dependence on them (Komalasari et al, 2021). One could argue that this gradual reduction in use can limit the adverse consequences that would usually be seen in the complete removal of drugs from prisons as investigated by Dillon (2001). While there can be a certain stigma around OAT in prisons, it is hoped that by providing this treatment in the TCs themselves, that drug using prisoners will not have the ability to stigmatise or bully others that avail of this (Komalasari et al, 2021).

The use of this dual drug strategy focusing on both increasing security and increasing treatment availability has been shown to achieve positive results (Duke, 2003). Additionally, research has shown that implementing a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments is far more effective at reducing recidivism and aiding recovery than simply using one or the other (Sondhi et al, 2020). Completion of these interventions in TCs mixed with continuity of treatment post-release in the community is more successful at reducing reoffending and relapse than any other program (Komalasari et al, 2021; Haviv & Hasisi, 2019; Alsan, 2018; Mitchell et al, 2012).

Further Security Measures

- Slight reduction in the use of drug dogs due to their ineffectiveness in detecting NPS, owing to their constantly changing nature (Vaccaro et al, 2022; Ralphs et al, 2017).

- Potential for these saved funds to be allocated towards new transmission x-ray machines.

- Reduced numbers of drug dogs used still detect the less common, more traditional drugs or other items smuggled in (Jezierski et al, 2014).

- Increase security and observation at the perimeter of prisons, to prevent perimeter breaches (Tompkins, 2016).

- Inspect and/or photocopy mail, so that prisoners do not receive the original, which could be sprayed with NPS (Norman, 2022).

References

Abderhalden, FP., (2022), ‘Environmental and Psychological Correlates of Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors among Jail Detainees’, Corrections, Oxfordshire: Routledge, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23774657.2021.2023339 Accessed on the 23rd of November, 2023.

Alsan, L., (2018), ‘Doing time on a TC: how effective are drug-free therapeutic communities in prison? A review of the literature’, Therapeutic communities: The international journal of therapeutic communities, vol. 39(1), pp.26-34, Leeds: Emerald Publishing.

Azbel, L., Rozanova, J., Michels, I., Altice, FL., and Stover, H., (2017), ‘A qualitative assessment of an abstinence-oriented therapeutic community for prisoners with substance use disorders in Kyrgyzstan’, Harm Reduction Journal, vol. 14(43), London: Biomed Central.

Bacon, M., and Spicer, J., (2022), ‘‘Breaking supply chains’. A commentary on the new UK Drug Strategy’, International Journal of Drug Policy, vol. 109(0), pp. 1-11, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cao, L., Zhao, J., and Van Dine, S., (1997), ‘Prison Disciplinary Tickets: A Test of the Deprivation and Importation Models’, Journal of Criminal Justice, vol. 25(2), pp. 103-113, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Colvin, M., (2007), ‘Applying Differential Coercion and Social Support Theory to Prison Organisations: The Case of the Penitentiary of New Mexico’, The Prison Journal, vol. 87(3), pp. 367-387, London: Sage.

Cope, N., (2003), ‘’It’s No Time or High Time’: Young Offenders’ Experiences of Time and Drug Use in Prison’, The Howard Journal, vol. 42(2), pp. 158-175, USA: Blackwell Publishing.

Costantino, AG., Altomare, C., and Stella, A., (2019), ‘Chapter 16- Issues of false negative results in toxicology: difficult in detecting certain drugs and issues with detection of synthetic cathinone (bath salts), synthetic cannabinoids (spice), and other new psychoactive substances’, Accurate Results in the Clinical Laboratory: A Guide to Error Detection and Correction, second edition, pp. 257-270, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Davis, CG., Doherty, S., and Moser, AE., (2014), ‘Social Desirability and Change Following Substance Abuse Treatment in Male Offenders’, Psychology of Addictive Behaviours, vol. 28(3), pp. 872-879, Washington: American Psychological Association.

DeLisi, M., Trulson, CR., Marquart, JW., Drury, AJ., and Kosloski, AE., (2011), ‘Inside the Prison Black Box: Toward a Life Course Importation Model of Inmate Behavior’, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, vol. 55(8), pp. 1186-1207, London: Sage.

Dillon, L., (2001), Drug use among prisoners: an exploratory study, Dublin: Health Research Board.

Doyle, MF., Shakeshaft, A., Guthrie, J., Snijder, M., and Butler, T., (2019), ‘A systematic review of evaluations of prison-based alcohol and other drug use behavioural treatment for men’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, vol. 43(2), pp.120-130, Australia: The Public Health Association of Australia.

Duke, K., (2003), Drugs, Prisons and Policy Making, New York: Springer.

Duke, K., (2020), ‘Producing the ‘problem’ of new psychoactive substances (NPS) in English prisons’, International Journal of Drug Policy, vol. 80(0), pp. 1-8, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Edgar, K., and O’Donnell, I., (1998), Mandatory drug testing in prisons: An evaluation, research findings, no. 75, London: Home Office.

Haviv, N., and Hasisi, B., (2019), ‘Prison Addiction Program and the Role of Integrative Treatment and Program Completion on Recidivism’, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, vol. 63(15-16), pp. 2471-2770, London: Sage.

Hendrich, D., Alves, P., Farrell, M., Stover, H., Moller, L., and Mayet, S., (2011), ‘The effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment in prison settings: a systematic review’, Addiction, vol. 107(0), pp. 501-517, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

HM Inspectorate of Prisons., (2015), Changing patterns of substance misuse in adult prisons and service responses, London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons.

HM Prison & Probation Service., (2019), Prison Drugs Strategy, Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5ca4844b40f0b625e7f496aa/prison-drugs-strategy.pdf Accessed on the 2nd of December 2023.

Hochstetler, A., and DeLisi, M., (2005), ‘Importation, deprivation and varieties of serving time: An integrated-lifestyle-exposure model of prison offending’, Journal of Criminal Justice, vol. 33(0), pp. 257-266, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Holland, A., Stevens, A., Harris, M., Lewer, D., Sumnall, H., Stewart, D., Gilvarry, E., Wiseman, A., Howkins, J., McManus, J., Shorter, GW., Nicholls, J., Scott, J., Thomas, K., Reid, L., Day, E., Horsley, J., Measham, F., Rae, M., Fenton, K., and Hickman, M., (2022), ‘Analysis of the UK Government’s 10-Year Drugs Strategy- a resource for practitioners and policymakers’, Journal of Public Health, vol. 45(2), pp. 215-224, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jewkes, Y., Bennett, J., and Crewe, B., (2016), Handbook on Prisons, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Jezierski, T., Adamkiewicz, E., Walczak, M., Sobcynka, M., Gorecka-Bruzda, A., Ensminger, J., and Papet, E., (2014), ‘Efficacy of drug detection by fully trained police dogs varies by breed, training level, type of drug and search environment’, Forensic Science International, vol. 237(0), pp. 112-118, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Kanato, M., (2008), ‘Drug use and health among prison inmates’, Current Opinion in Psychiatry, vol. 21(3), pp. 252-254, Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer.

Keene, J., (1997), ‘Drug Use Among Prisoners Before, During and After Custody’, Addiction Research, vol. 4(4), pp. 343-353, Amsterdam: Hardwood Academic Publishers.

Kolind, T., and Duke, K., (2016), ‘Drugs in prisons: Exploring use, control, treatment and policy’, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, vol. 23(2), pp.89-92, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis.

Komalasari, R., Wilson, S., and Haw, S., (2021), ‘A systematic review of qualitative evidence on barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of opioid agonist treatment (OAT) programmes in prisons’, International Journal of Drug Policy, vol. 87(0), pp. 1-9, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Liebling, A., and Maruna, S., (2011), The Effects of Imprisonment, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Linhorst, DM., Dirks-Linhorst, PA., and Groom, R., (2012), ‘Rearrest and Probation Violation Outcomes Among Probationers Participating in a Jail-Based Substance-Abuse Treatment Used as an Intermediate’, Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, vol. 51(0), pp. 519-540, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Mason, R., Smith, M., Onwuegbusi, T., and Roberts, A., (2022), ‘New Psychoactive Substances and Violence within a UK Prison Setting’, Substance Use & Misuse, vol. 57(14), pp. 2146-2150, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis.

McLaughlin, E., and Muncie, J., (2001), The Sage Dictionary of Criminology, London: Sage.

Mehta, P., and Smith-Bindman, R., (2011), ‘Airport Full-Body Screening: What is the Risk?’, Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 171 (12), pp. 112-115, Chicago: American Medical Association.

Michalski, JH., (2017), ‘Status Hierarchies and Hegemonic Masculinity: A General Theory of Prison Violence’, British Journal of Criminology, vol. 57(0), pp. 40-60, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, SG., Kelly, SM., Brown, BS., Reisinger, HS., Peterson, JA., Ruhf, A., Agar, MH., and Schwartz, MD., (2009), Incarceration and opioid withdrawal: The experiences of methadone patients and out-of-treatment heroin users’, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, vol. 41(2), pp. 145-152, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Mitchell, O., Wilson, DB., and MacKenzie, DL., (2012), ‘The Effectiveness of Incarceration-Based Drug Treatment on Criminal Behaviour: A Systematic Review’, Campbell Systematic Reviews, vol. 8(1), pp. 1-76, New Jersey: Wiley.

Mjaland, K., (2016), ‘Exploring prison drug use in the context of prison-based drug rehabilitation’, Drugs, Education, Prevention and Policy, vol. 23(2), pp. 154-162, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis.

Norman, C., (2022), ‘A global review of prison drug smuggling routes and trends in the usage of drugs in prisons’, Wires Forensic Science, vol. 5(2), Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/wfs2.1473 Accessed on the 22nd of November, 2023.

Nutt, D., (2019), ‘New psychoactive substances: Pharmacology influencing UK practice, policy and the law’, British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 86(0), pp. 445-451, New Jersey: Wiley.

Nutt, D., King, LA., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C., (2007), ‘Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse’, Health Policy, vol. 369(1), pp. 1047-1053, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities., (2022), Alcohol and drug treatment in secure settings 2020 to 2021: Report, Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/substance-misuse-treatment-in-secure-settings-2020-to-2021/alcohol-and-drug-treatment-in-secure-settings-2020-to-2021-report Accessed on the 23rd of November, 2023.

Opitz-Welke, A., Bennefeldt-Kersten, K., Konrad, N., and Welke, J., (2016), ‘Prison suicide in female detainees in Germany 2000-2013′, Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, vol. 44(0), pp. 68-71, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Page, G., (2017), ‘Rapid Review: Drug treatment in UK prisons. Treatment need, and treatment effectiveness’, Ex-Prisoners Recovering from Addiction (EPRA), Available at: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/spru/EPRA.%20Supporting%20paper%201.%20Review%20of%20Drug%20Treatment%20Need%20and%20Effectiveness%20in%20UK%20Prisons.%209.2.2017.pdf Accessed on the 27th of November 2023.

Penfold, C., Turnbull, PJ., and Webster, R., (2005) ‘Tackling Prison Drug Markets: An exploratory qualitative study’, Home Office Online Report 39/05, London: Home Office, Available at: http://www.antoniocasella.eu/archila/Tackling_39_05.pdf Accessed on the 23rd of November, 2023.

Ralphs, R., Williams, L., Askew, R., and Norton, A., (2017), ‘Adding Spice to the Porridge: The development of a synthetic cannabinoid market in an English prison’, International Journal of Drug Policy, vol. 40(0), pp. 57-69, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Rocheleau, AM., (2015), ‘Ways of Coping and Involvement in Prison Violence’, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, vol. 59(4), pp. 359-383, London: Sage.

Sacks, S., Melnick, G., Coen, C., Banks, S., Friedmann, PD., Grella, C., and Knight, K., (2007), ‘CJDATS Co-Occurring Disorders Screening Instrument for Mental Disorders (CODSI-MD)’, The Prison Journal, vol. 87(1), pp. 86-110, London, Sage.

Shafi, A., Berry, AJ., Sumnall, H., Wood, DM., and Tracy, DK., (2020), ‘New psychoactive substances: a review and updates’, Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, vol. 10(0), pp. 1-21, London: Sage.

Sinclair, S., and Hertzog, R., (2017), ‘A Review of Full Body Scanners: An Alternative to Strip Searches of Incarcerated Individuals: 2017 Report to the Legislature’, Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/300856.pdf Accessed on the 27th of November, 2023.

Sondhi, A., Leidi, A., and Best, D., (2020), ‘Estimating a treatment effect on recidivism for correctional multiple component treatment for people in prison with an alcohol use disorder in England’, Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, vol. 15(81), pp. 1-12, New York: Springer Nature.

Sykes, G., (1958), The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum-Security Prison, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Tompkins, CNE., (2016), ‘There’s that many people selling it”: Exploring the nature, organisation and maintenance of prison drug markets in England’, Drugs, Education, Prevention and Policy, vol. 23(2), pp. 144-153, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis.

Vaccaro, G., Massariol, A., Guirguis, A., Kirton, SB., and Stair, JL., (2022), ‘NPS detection in prison: A systematic literature review of use, drug form, and analytical approaches’, Drug Testing and Analysis, vol. 14(8), pp. 1350-1367, New Jersey: Wiley.

Watson, TM., (2016), ‘The Elusive Goal of Drug-Free Prisons’, Substance Use & Misuse, vol. 51(1), pp. 91-103, Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis.