Illegal Drug Use in Early Adolescence: A Quantitative Research Report – Chloe Carragher – 3rd Year Criminology with Quantitative Methods

I. Research Brief

This report explores how ‘social structures, individual circumstances, and traits each influence the lived experience of young people in Northern Ireland (N.I.)’, focusing on illegal drug use in adolescence. In the past, related studies have centred on young adults aged 15+ (Matthews et al., 2019), thus creating a disparity in the research of those aged 13-14. However, such analysis could be vital to early drug use intervention and used to inform policy change if required. Hence, this will be the target cohort for this report. Using Stata, the researcher aims to:

- Produce several logistic regression models to assess outcome variance

- Uncover potential sociological associations, and

- Address the key research question (R.Q.) –

2. Relevant Literature

Recent N.I. studies have centred on illicit substances in the context of political conflict or as a risk factor for other issues like prison misconduct, self-harm, and suicide (as explored by O’Connor et al., 2014; O’Neill & O’Connor, 2020; Butler et al., 2021a; 2021b). As a result, there is limited literature specific to area-level deprivation and criminal exposure (C.E.) without looking at other countries and studies that include adolescent drug use as a proxy indicator rather than an outcome. Hence, the researcher examines the following studies to establish a framework before analysis:

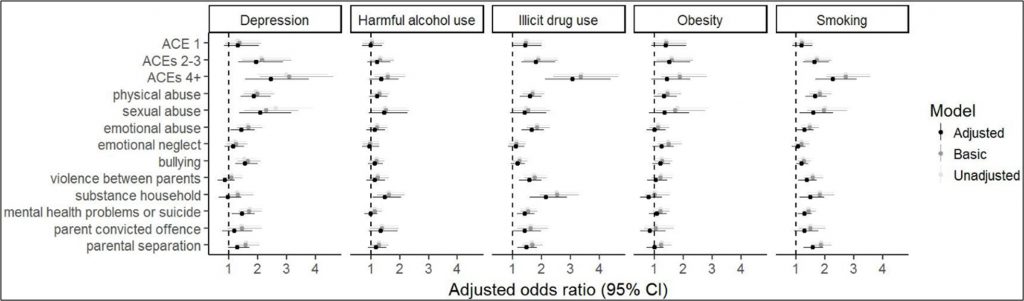

A study exploring associations between adverse childhood experiences (ACE), academic achievement, health, and other socioeconomic factors examined drug use as an outcome of health in adolescents aged 17 years (Houtepen et al., 2020). Logistic regression (see Appendix, Fig.1) showed that when compared to those without ACEs, respondents with 4+ACEs and lower academic achievement were 3.1 times more likely to report drug use (2.1–4.4, p < 0.001). Interactions between parental substance-use and respondent drug use were found cohort-wide but indicated greater associations for females with OR = 2.7 (1.8-4.0, p < 0.04) (males OR = 1.7 (1.1-2.6, p < 0.04) (Houtepen et al., 2020).

Researchers hypothesised that respondents in higher socioeconomic positions would display weaker associations between adverse outcomes (i.e., drug use) and ACEs, presuming their social circumstances may ‘mitigate the effects. However, no evidence was observed to support this. Furthermore, whilst this study provided a thorough analysis of the observed cohort, the generalisability of the findings is questionable due to location constraints, particularly because respondents were based in Southwest England (an area of low diversity and high socioeconomic status compared to the national average) (Houtepen et al., 2020).

A further study investigating adolescent substance use across 8 European countries found similar sociodemographic associations. While the primary focus surrounded drug use and sexuality, the analysis accounted for not only single-use responses (e.g., cannabis only) but also multiple-use (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis) and adjusted for gender, family affluence, and regionality, thus, held other overlapping areas of interest (Költő et al., 2019).

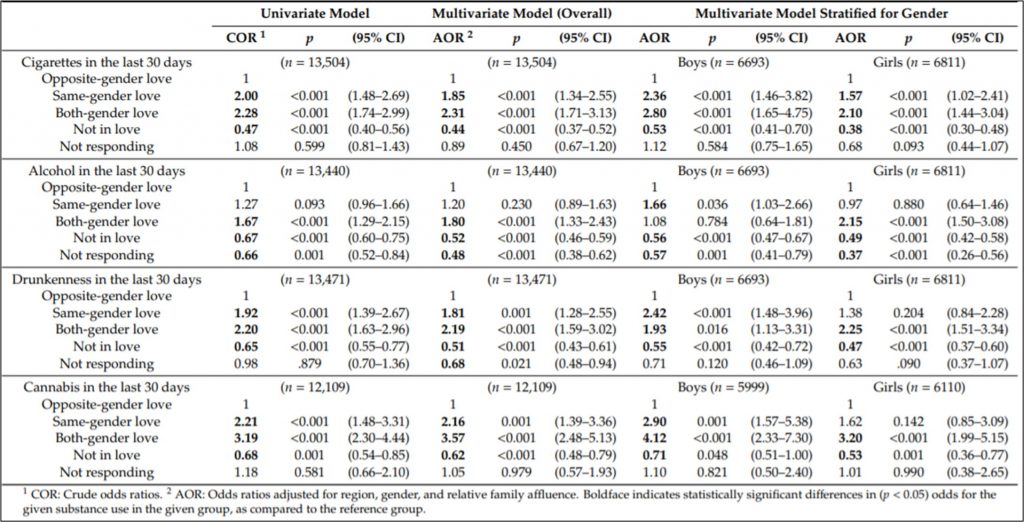

To obtain odds ratios for each outcome, both univariate and multivariate models were constructed with heterosexuality as a reference group (see Appendix, Fig.2). Interestingly, the gender-stratified model indicated that when compared to sexual minority females, sexual minority males were more likely to report drunkenness and alcohol, cigarette, and cannabis use in the last 30 days[1]. Although this suggests gender is a strong indicator even in groups with higher levels of drug use cohort-wide, as deprivation score is not measured, the researcher cannot say for certain that this may also be the case for those in high deprivation areas (Költő et al., 2019).

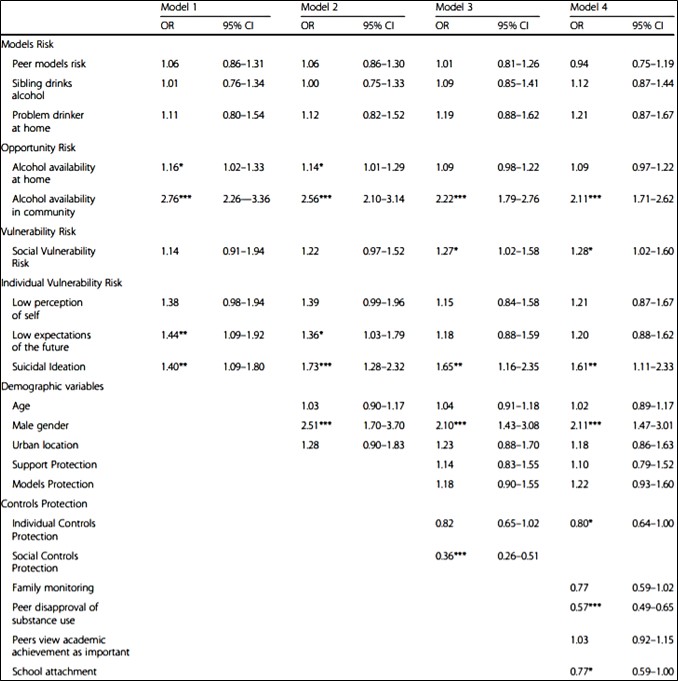

Another study examined associations between adolescent drug use and risk, protective, and demographic factors using 17 post-primary schools in Botswana (Riva et al., 2018). Using multivariate binomial logistic regression, researchers constructed four models which adjusted for clustered data (see Appendix, Fig.3). This revealed that compared to their female peers, males were 2.2 times more likely to report drug use (1.6-3.0, p ≤ 0.001) – suggesting an association between gender and drug use. However, from a sociological standpoint, this may be due to factors like gender roles and status expectations rather than an inherent predisposition to drug use that only males experience (Riva et al., 2018; Naeim et al., 2021). This study also found that when compared to respondents in ‘low-risk’ environments, those in ‘high-risk’ environments were 3.5 times more likely to report drug use (2.9-4.4, p ≤ 0.001); indicating that living in a neighbourhood with C.E./access to illicit substances may contribute to drug use. However, as participants only measure drug use through self-disclosure, the potential for socially desirable answers is likely[2]. Thus, all findings should be observed with this in mind (Riva et a., 2018).

3. Hypothesis

Considering the aforementioned, the researcher hypothesises that whilst area-level deprivation and C.E. may explain some variation in drug use, it will likely not explain it all. Instead, early-onset drug use is likely a combination of many interlocking ‘social structures, individual circumstances, and traits’.

II) Methodology

1. Dataset Breakdown

The Belfast Youth Development Study (BYDS) was created in response to research disparities in the ‘initiation, persistence, and resistance of substance use, alongside life course processes in adolescence and adulthood’ (Higgins et al., 2018, pp.1). It investigated substance use amongst N.I.’s post-primary students aged 10-15 and ‘emerging adults’ aged 16-21 from 2000-2011 through seven data collection waves.

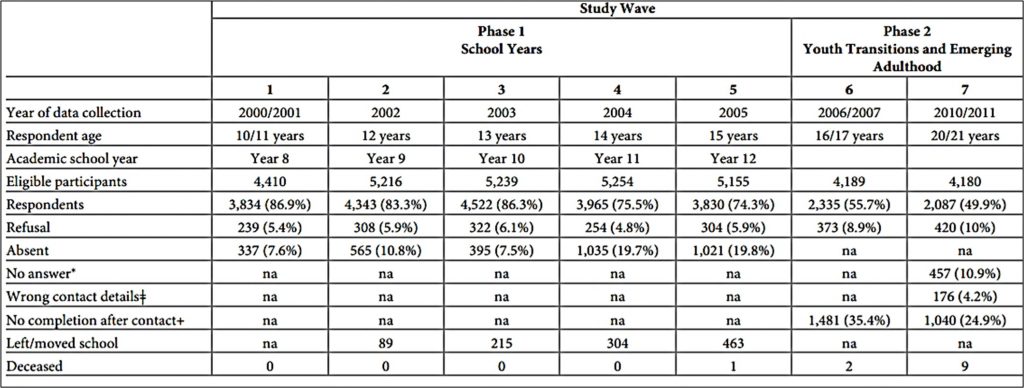

For this project, Wave 3 was employed in isolation as it exclusively observed substance use amongst the cohort of interest (aged 13-14) and held the largest number of respondents of all collection waves (see Appendix, Fig.4). This sample comprised 34 post-primary schools in Ballymena, Belfast, and Downpatrick and targeted all Year 10 students in participating schools. It had a high response rate of 86.3% (n=4,522), 6.1% refused to answer (n=322), and 7.5% were absent from school when the data was collected (n=395). This wave consisted of 85 variables and captured a range of sociodemographic measures, including family structure, socioeconomic status, and gender (which was almost equally distributed with 47.7% male respondents and 52.1% female, 0.2% did not respond[3]) (Higgins et al., 2018).

The researcher notes that whilst this dataset aligns with the R.Q.; it is not without limitations. As it was compiled in 2003, it will not accurately reflect drug use amongst early adolescents today, in addition; the sample may not reflect all of N.I. as participating schools were localised to just 2 (i.e., County Antrim and County Down) of the six counties in N.I. (Higgins et al., 2018).

2. Measures and Data Manipulation

Area-level deprivation: Deprivation theory suggests lack of services, support, and opportunity leads to substance use to escape, self-medicate, or rebel (Karriker-Jaffe, 2011); hence, it was utilised as a proxy. This was measured by one predictor (N.I. Multiple Deprivation Measure score), which combined weighted variables: income (25%), employment (25%), healthcare/disability (15%), education, skills, and training (15%), geographical access to services (10%), social environment (5%), and housing stress (5%), to create a standardised measure of area-level deprivation which can be compared (Nobel et al., 2001;2006). This was converted to a z-score to standardise the raw value of the normal distribution.

Criminal exposure: As previously stated, high neighbourhood crime levels may increase access to illegal substances (Riva et al., 2018; Engström, 2021). As a result, C.E. was used as a proxy measured by two predictor variables: 1. whether the respondent had/had not seen drug use or selling in their neighbourhood, and 2. whether the respondent stated there was/was not lots of crime where they live.

C.E. variable 1. originally had seven values: ‘almost never/never’ (1), ‘not very often (2), ‘sometimes’ (3), ‘often’ (4), ‘almost always/always’ (5), multiple answers (6), ‘no reply’ (7). This was recoded as ‘almost never/never’ (1=1), ‘not often/sometimes’ (2/3=2), ‘often/always’ (4/5/6=3), with ‘no reply’ recoded as missing (7=.). C.E. variable 2. was recoded as above but had no multiple answers to recode.

Drug use: This was measured by two variables: 1. self-disclosure of cannabis use in the last year and 2. self-disclosure of cocaine use in the last year. The original variables had four values: ‘yes’ (1), ‘no’ (2), ‘not sure’ (3), and ‘no reply’ (4). These were recoded to create two binary variables; ‘yes’ remained the same (1=1), and ‘No reply’ was recoded as missing (3=.). Observations of no disclosure of drug use and ‘not sure’ were combined and set as the reference group as it was presumed the respondent would be aware if they had used drugs. Subsequently, those unsure will likely have not (2/3=0).

Although observed in the dataset, alcohol, tobacco, and solvent use were not analysed – the researcher opted to focus on Class A and B drugs as less socially acceptable and ‘harder to access’ substances (Blanco et al., 2018).

Other traits of interest:

Gender: As the literature suggests, females are less likely to use drugs (relative to their male peers). This was included as a control. This was measured through the respondent’s self-defined gender when asked, ‘Are you a boy or a girl?’. The original variable had three values: ‘boy’ (1), ‘girl’ (2), and ‘no reply’ (3). A dummy was created with ‘boy’ as the reference group (1=0), ‘girl’ was given a new value (2=1), and ‘no reply’ was recoded as missing (3=.). The new dummy variable was labelled ‘female’.

Free school meal (FSM) eligibility: Eligibility indicates low household income; according to deprivation theory, this may increase drug use (Allen, 2016; Meshesha et al., 2018). The original variable had four values: ‘yes’ (1), ‘no’ (2), ‘don’t know’ (3), and ‘no reply’ (4). When recoded, ‘yes’ remained the same (1=1), ‘no’ and ‘don’t know’ were combined (again presuming the respondent would be aware if they were eligible); this was set as the reference group (2/3=0). Finally, ‘No reply’ was recoded as missing (3=.).

3. Analytical Procedure

After recoding, descriptive statistics were carried out. This showed that whilst 90% of respondents did not disclose cocaine use (n=2,138), 3% reported use in the last year (n=77). Similarly, most respondents did not disclose cannabis use (n=1,686). However, almost a quarter reported use in the last year (n=524). There was a high number of missing responses for both (n=153, n=158), potentially due to the sensitive nature of the topic and a reluctance to self-disclose use (Hardland et al., 2021).

Logistic regression was performed to create three different models for cocaine use (Table 1) and cannabis use (Table 2), which could assess the statistical significance and association strength of all variables of interest. Model 1 adjusts for deprivation, model 2 adjusts for C.E., and model 3 adjusts for both. All models include gender and FSM eligibility as controls.

III) Research Findings

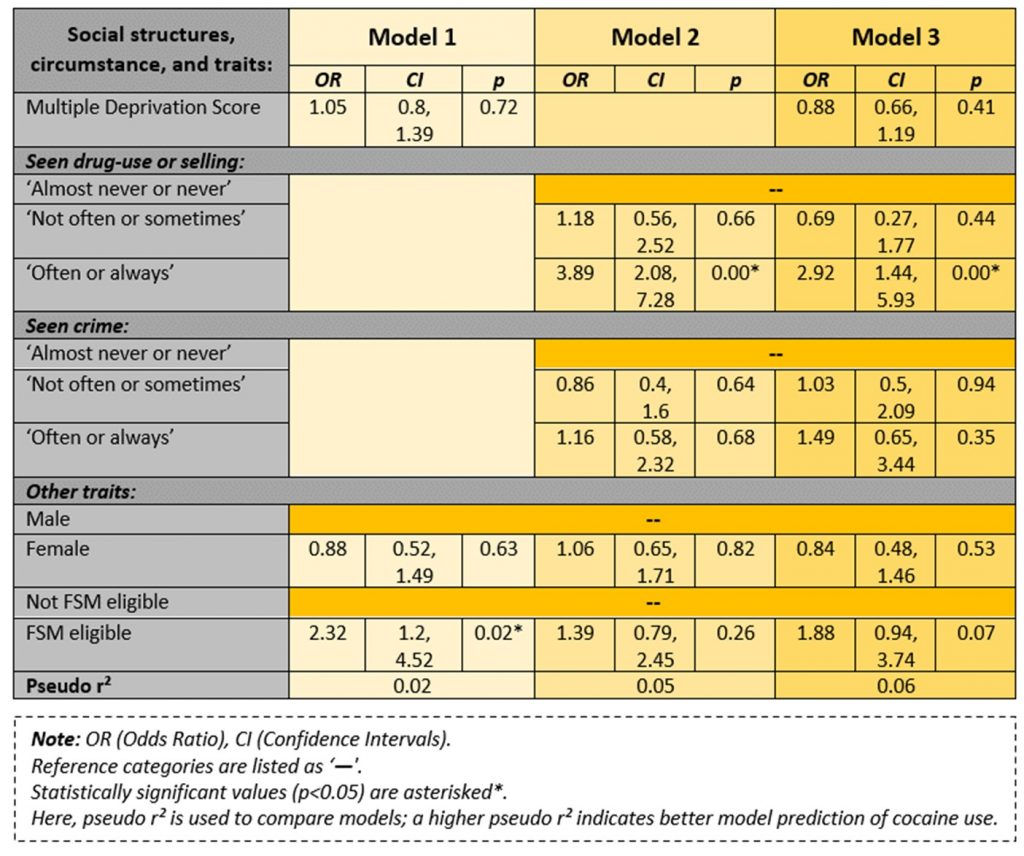

Table 1: Cocaine use when controlling for social structures, circumstances, and traits.

Model 1 indicates that deprivation (when controlling for other listed traits) alone is not a statistically significant predictor of cocaine use as p>0.05 (0.8-1.39). Whilst gender differences do not indicate any significant association, respondents eligible for FSM do (p<0.05, 1.2-4.52) – they have a higher likelihood (x2.3) of reporting cocaine use when compared to ineligible respondents.

Model 2 shows CE (when controlling for other listed traits) is overall not a strong predictor; however, those who report seeing drug use/selling ‘often or always have a higher likelihood (x3.89) of reporting cocaine use themselves (p<0.05, 2.08-7.28).

Model 3 is adjusted for all variables of interest; it indicates a slight change from Model 2, but again only those who report seeing drug use/selling ‘often or always’ show a statistically significant association with self-reported cocaine use (x2.92 greater than those who reported ‘rarely/never, p<0.05, 1.44-5.93). Pseudo r² indicates a narrow difference between all models, with model 3 being the best predictor of cocaine use overall but only accounting for minute variation.

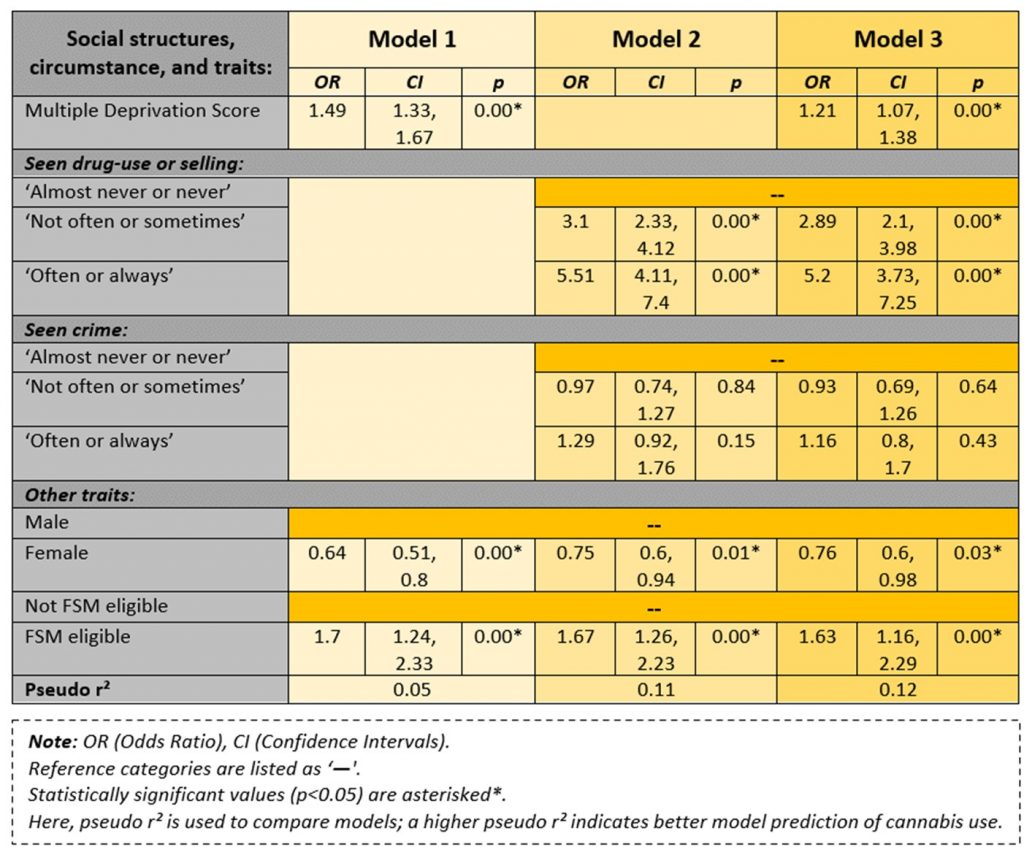

Table 2: Cannabis use when controlling for social structures, circumstances, and traits.

Model 1 indicates a statistically significant positive association between deprivation (when controlling for other listed traits) and cannabis use (p<0.05, 1.33-1.67). In addition, both controls show significant influence, with females being 36% less likely (OR=0.64, p<0.05, 0.51-0.8) to report cannabis use than their male peers, and FSM eligible respondents being 70% more likely (OR=1.7, p<0.05, 1.24-2.33) than their peers who are not eligible.

Model 2 indicates that associations differ depending on the type of C.E. Seeing any degree of drug use/selling in their area, i.e., ‘not often…’ (p<0.05, 2.33-4.12) to ‘…always’ (p<0.05, 4.11-7.4) increases the likelihood of disclosing cannabis use by up to 5.51 times when compared to those who reported ‘almost never/never’ seeing drug use/selling. However, there was no significant association between the general area crime variable and the personal use of cannabis, regardless of frequency. Both controls remain significant but show females as 25% less likely (OR=0.75, p<0.05, 0.6-0.94) and FSM eligible respondents as 67% more likely (OR=1.67, p<0.05, 1.26-2.23) to report cannabis use.

Model 3 is fully adjusted for all variables of interest but displays figures similar to model 2. As expected, the ‘seen crime’ measure is the only non-significant value (p>0.05). Those who reported seeing drug use/selling were 2.89-5.2 times more likely to report cannabis use depending on sighting frequency (p<0.05), and again, those with higher levels of deprivation were also more likely (OR=1.21, p<0.05, 1.07-1.38). Pseudo r² shows the minimal difference between models 2 and 3. However, the larger difference between models 1 and 2 suggests C.E. explains more variation than deprivation score.

IV) Discussion

IV. I | Interpreting the Findings

From the results, it is clear that ‘social structures, individual circumstances, and traits each influence the lived experience of young people in N.I.’. The initial hypothesis is supported: whilst some variation can be explained by deprivation, C.E., and the controls, the extent fluctuates according to drug type.

All observed factors appear to have stronger associations with cannabis than cocaine, partly due to the small figure of cocaine disclosure (3%) within the sample. However, the gateway theory could provide a partial explanation, suggesting that most users start with recreational substances and move to more serious use in later adolescence (Kandel et al., 1992). This may coincide with other arguments of drug accessibility, which state that some drugs are not associated with high deprivation in early adolescence because they are too expensive for individuals with very little (if any) flexible income. Subsequently, it is perhaps unsurprising that cannabis user levels are higher (22%) in a cohort aged 13-14 (Jorgensen & Wells, 2021). The drug-accessibility argument is further supported as respondents who reported high levels of seeing drug use or selling in their area were the only group to display a statistically significant greater likelihood of taking cocaine and cannabis. Interestingly, for both cocaine and cannabis users, the frequency of general crime in their area appeared to have no significant association. Whilst this may be an accurate reflection of the Ballymena, Belfast, and Downpatrick areas, it may be in part due to the subjectivity of the question and how each respondent defines ‘crime’ (Gadd & Farrall, 2008).

Like other studies (see I.2), the findings indicate females were less likely to report drug use. There are conflicting theories as to why this might be; it has been suggested that males hold a pro-drug stance that is not reciprocated by their female peers (Chan, 2021). However, this is heavily critiqued by behavioural-focused scholars who assert that mannerisms associated with drug use (i.e., impulsivity, high risk) overlap with what is considered masculine traits/gendered expectations for men. As a result, it is argued that this deters women and encourages men to use illegal substances (Chan, 2021).

Although this study produced valid results comparable to other literature, it was not without limitations. In addition to the potential for socially desirable answers, the high number of missing responses may impact the reliability of the findings (Denman et al., 2018). Similarly, location constraints may impact results generalisability (Riva et al., 2018) and may not reflect border/ rural areas. Lastly, as previously stated, the dataset used is almost two decades old and may not be entirely representative of young adolescents currently living in N.I.

Nevertheless, due to the continuance of socioeconomic inequalities coupled with the glacial speed of changes to policy and practice for those in the most vulnerable areas with the greatest need, it is likely that both deprivation and C.E. influence drug use (Bywaters et al., 2020). Though this claim cannot be fully supported without further investigation – thus, the researcher proposes that this study should not only be repeated using more recent data but also using variables that encompass other illicit drugs on the rise in N.I., for example, novel psychoactive substances (Gittins et al., 2018; Darke et al., 2021).

Bibliography

Allen, C. (2016). Crime, Drugs and Social Theory: A Phenomenological Approach (online ed.). Routledge. Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.4324/9781315258959 [Accessed on 14.12.21]

Blanco, C., Flórez-Salamanca, L., Secades-Villa, R., Wang, S., & Hasin, D.S. (2018). ‘Predictors of initiation of nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine use: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)’, The American Journal on Addictions, 27(6), pp.477-484. Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1111/ajad.12764 [Accessed on 14.12.21]

Butler, M., McNamee, C.B., & Kelly, D. (2021a). ‘Exploring Prison Misconduct and the Factors Influencing Rule Infraction in Northern Ireland’, European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 27(4), pp. 1-20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-021-09491-6 [Accessed on 11.12.21]

Butler, M., McNamee, C.B., & Kelly, D. (2021b). ‘Risk Factors for Interpersonal Violence in Prison: Evidence From Longitudinal Administrative Prison Data in Northern Ireland’, The British Journal of Interpersonal Violence, [Online]. Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1177%2F08862605211006363 [Accessed on 11.12.21]

Bywaters, P., Scourfield, J., Jones, C., Sparks, T., Elliott, M., Hooper, J., McCartan, C., Shapira, M., Bunting, L., & Daniel, B. (2020). ‘Child welfare inequalities in the four nations of the U.K.’, Journal of Social Work, 20(2), pp. 193–215. Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1177%2F1468017318793479 [Accessed on 16.12.21]

Chan, C. (2021). ‘Investigating Attitudes Towards Drug Use; Age and Gender Differences’, Undergraduate thesis, Dublin: National College of Ireland. Available at: http://norma.ncirl.ie/id/eprint/4939 [Accessed on 16.12.21]

Darke, S., Banister, S., Farrell, M., Duflou, J., & Lappin, J., (2021) ‘“Synthetic cannabis”: A dangerous misnomer’, International Journal of Drug Policy, 98(1). Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103396 [Accessed: 20.12.21].

Denman, D.C., Baldwin, A.S., Betts, A.C., McQueen, A., & Tiro, J.A.(2018). ‘Reducing “I Don’t Know” Responses and Missing Survey Data: Implications for Measurement’, Medical Decision Making, 38(6), pp.673-682. Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1177/0272989X18785159 [Accessed on 13.12.21]

Gadd, D., & Farrall, S. (2008). Crime, Criminal Justice and Masculinities (online ed.). Routledge. Available at: https://www-taylorfrancis-com.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315095295-13/criminal-careers-desistance-subjectivity-david-gadd-stephen-farrall [Accessed on 16.12.21]

Gittins, R., Guirguis, A., Schifano, F., & Maidment, I. (2018). ‘Exploration of the Use of New Psychoactive Substances by Individuals in Treatment for Substance Misuse in the U.K.’, Brain Sciences. MDPI AG, 8(4), pp. 58. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8040058 [Accessed on: 20.12.21].

Harland J., Henry-Edwards S., Gowing L., & Ali, R. (2021). ‘Brief Intervention for Illicit Drug Use’, In: el-Guebaly N., Carrà G., Galanter M., Baldacchino A.M. (eds) Textbook of Addiction Treatment. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36391-8_45 [Accessed on 13.12.21]

Higgins, K., McLaughlin, A., Perra, O., McCartan, C., McCann, M., Percy, A., & Jordan, J-A. (2018). ‘The Belfast Youth Development Study (BYDS): A prospective cohort study of the initiation, persistence, and desistance of substance use from adolescence to adulthood in Northern Ireland’, PLoS ONE, 13(5). Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0195192 [Accessed on 10.12.21]

Houtepen, L.C., Heron, J., Suderman, M.J., Fraser, A., Chittleborough, C.R., & Howe, L.D. (2020). ‘Associations of adverse childhood experiences with educational attainment and adolescent health and the role of family and socioeconomic factors: A prospective cohort study in the U.K.’, PLoS MEDICINE, 17 (3). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003031 [Accessed on 11.12.21]

Jorgensen, C., & Wells, J. (2021). ‘Is marijuana really a gateway drug? A nationally representative test of the marijuana gateway hypothesis using a propensity score matching design’, Journal of Experimental Criminology, pp.1-18. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09464-z [Accessed on 16.12.21]

Kandel, D.B., Yamaguchi, K., & Chen, K. (1992). ‘Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the gateway theory’, Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53(5), pp.447-457. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1992.53.447 [Accessed on 16.12.21]

Karriker-Jaffe, K.J. (2011). ‘Areas of disadvantage: A systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes’, Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(1), pp. 84-95. Available at: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x [Accessed on 11.12.21]

Költő, A., Cosma, A., Young, H., Moreau, N., Pavlova, D., Tesler, R., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Vieno, A., Saewyc, E. M., & Nic Gabhainn, S. (2019). ‘Romantic Attraction and Substance Use in 15-Year-Old Adolescents from Eight European Countries’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. MDPI AG, 16(17). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173063 [Accessed on 12.12.21]

Matthews, T., Danese, A., Caspi, A., Fisher, H. L., Goldman-Mellor, S., Kepa, A., Moffitt, T. E., Odgers, C. L., & Arseneault, L. (2019). “Lonely young adults in modern Britain: findings from an epidemiological cohort study,” Psychological Medicine. Cambridge University Press, 49(2), pp. 268–277. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/lonely-young-adults-in-modern-britain-findings-from-an-epidemiological-cohort-study/2AD2B6E4613435CDF85BC4359DD51A1B# Accessed on: 20.12.21].

Meshesha, L. Z., Utzelmann, B., Dennhardt, A. A., & Murphy, J. G. (2018). ‘A behavioral economic analysis of marijuana and other drug use among heavy drinking young adults’, Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(1), pp.65–75. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000144 [Accessed on 14.12.21]

Naeim, M., Rezaeisharif, A., & Kamran, A. (2021) ‘The Role of Impulsivity and Cognitive Emotion Regulation in the Tendency Toward Addiction in Male Students’, Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment, 20 (4) pp. 278-287. Available at: https://journals.lww.com/addictiondisorders/Abstract/2021/12000/The_Role_of_Impulsivity_and_Cognitive_Emotion.9.aspx [Accessed on 12.12.21]

Noble, M., Lloyd, M., Wright, G., Dibben, C., & Smith, G. (2001). ‘Developing deprivation measures for Northern Ireland’, Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, 31(1), pp. 1-25. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2262/1517 [Accessed on 11.12.21

Noble, M., Wright, G., Smith, G., & Dibben, C. (2006). ‘Measuring multiple derivation at the small-area level’, Environment and Planning, 38(1), pp. 169-185. Available at: https://journals-sagepub-com.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1068/a37168 [Accessed on 11.12.21]

O’Connor, R.C., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2014). ‘Adolescent self-harm: A school-based study in Northern Ireland’, Journal of Affective Disorders, 159, pp. 46-52. Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.015 [Accessed on 11.12.21]

O’Neill, S., & O’Connor, R.C. (2020). ‘Suicide in Northern Ireland: epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention’, The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), pp. 538-546. Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30525-5 [Accessed on 11.12.21]

Riva, K., Allen-Taylor, L., Schupmann, W.D., Mphele, S., Moshashane, N., & Lowenthal, E.D. (2018). ‘Prevalence and predictors of alcohol and drug use among secondary school students in Botswana: a cross-sectional study’, BMC Public Health, 18 (1396), pp. 1-14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6263-2 [Accessed on 12.12.21]

Shafi, A., Gallagher, P., Stewart, N., Martinotti, G., & Corazza, O., (2017). ‘The risk of violence associated with novel psychoactive substance misuse in patients presenting to acute mental health services’, Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 32(3). Available at: https://doi-org.queens.ezp1.qub.ac.uk/10.1002/hup.2606 [Accessed on: 20.12.21].

Appendix

Fig. 1: ‘Forest plots for the associations of the ACE score and separate ACEs with poor health outcomes’ (Houtepen et al., 2020).

***’The reference category for each category of the ACE score (1, 2–3, and 4+) is experiencing 0 ACEs. The basic model is adjusted for sex. The adjusted model additionally includes home ownership, maternal and partner education, household social class, parity, ethnicity, maternal age, maternal marital status, and maternal and partner depression during pregnancy. ACE, adverse childhood experience; CI, confidence interval’***

Fig. 2: ‘Crude and adjusted odds for the four types of substance use, overall and by gender’ (Költő et al., 2019).

Fig. 3: ‘Binominal logit models of risk and protective factors predicting drug use among secondary school students in Botswana’ (Riva et al., 2018).

Statistically significant values are asterisked (***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05).

Fig. 4: Number of participants per wave (Higgins et al., 2018).

***‘Percentages are based on eligible participants. Eligible participants were all students enrolled in their schools participating year group including all recently enrolled students (even if they had not participated in previous waves). Students who had left a school were removed from the list of eligible participants. The eligible participant list also includes those who were unable to take part due to industrial action. Eligible participants total includes respondents, refusal, absent, no answer, wrong contact details, and no completion after contact. The source of these numbers was the student registry at each school. Total number of respondents = 5,809’***

[1] With the exception of alcohol consumption in bisexual females.

[2] As this method is also used for this project (see II.1), the researcher notes this as a potential limitation.

[3] Potentially due to lack of gender-inclusive answers (i.e., no option for gender-fluid, transgender individuals, etc.)