In a ESRC Festival of Social Science event, we presented some of the findings of the study to an audience mostly comprised of educational professionals, as well as parents and governors of rural schools. We also published a report of the findings so far, which you can download from here.

The event, entitled ‘The future of small rural schools in Northern Ireland’, involved a panel discussion after our presentation. The seven panellists included representatives from the Education Authority, the Department of Education, the Rural Community Network, the Integrated Education Fund and the Independent Review of Education, a University of Ulster academic, and a retired ETI inspector and principal. After the panellists introduced themselves, the audience were able to ask questions.

The study data collection has not been fully finalised yet. However, after selecting five schools to take part in our case studies, we have already interviewed and talked to their principals, teaching and non-teaching staff, parents, pupils and Governors. Thus, some analysis of these data revealed a range of findings as listed in our Slugger O’Toole blog piece.

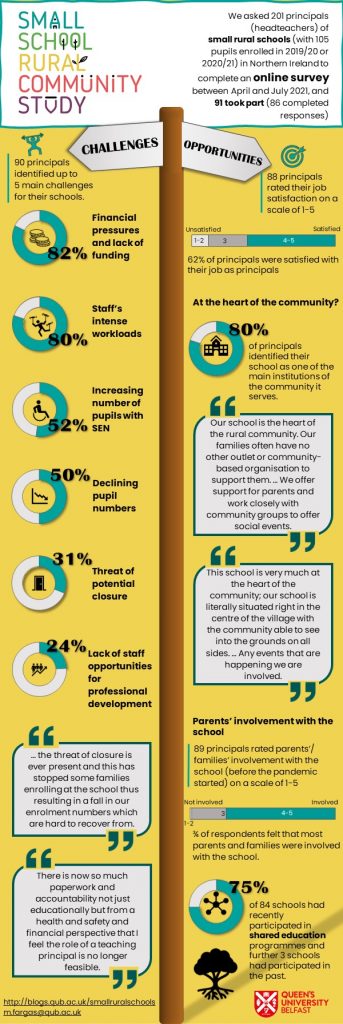

Despite their diversity and in line with some of the findings from international research, small rural schools in Northern Ireland face similar challenges, most common being financial pressures and staff’s intense workloads (including teaching principals’ dual/multiple role). For many of these schools, particularly those with smaller pupil numbers, falling pupil numbers and the threat of closure is especially significant and (judging by the survey findings) negatively affects principals’ job satisfaction. Partly because of the policy context of area planning, the smaller schools appear particularly susceptible to rumour and speculation notably around closure, with parents in the community less likely to enroll their children when imagining that they will not be able to continue in the same school.

Small rural schools are also perceived to have similar strengths, most common being their strong relationship with the community, the low pupil-to-teacher ratio (ideal to meet children’s individual needs), and the family-like environment where everybody knows and supports each other.

Small rural schools are a big part of their rural communities. Some are perceived to be ‘at the heart of the community’. This can mean different things depending on the school, but they often are a ‘meeting point’ where people come together. Schools organise community events, share resources with different groups, and contribute to the economy of the area, among many other things.

sLUGGER O’TOOLE, 2022/10/22

Our research has also featured in the BBC local news and the Irish News.