Reform: What is the point of the Lords?

The House of Lords

Historically, the House of Lords (the Lords) has been made up from aristocrats, church figures, and judges. There are 795 members within the House of Lords, and while this may seem like a lot, it is nothing compared to 1999 pre-reform membership totalling 1300 (Russell & Sciara 2007). The House of Lords Act, passed in 1999 under Labour Party reforms, removed most hereditary peers. Since then, Lords have been allowed to resign or retire (Russell & Sciara 2007).

The Party System in the House of Lords

In the Lords, at least up until 1999, it was dominated by the Conservative Party. As a result, often Labour governments would face defeats far more than Conservatives would. As previously aforementioned, however, now that hereditary peers were removed in 1999 Labour reforms, challenges by Lords were far more confident and took a much different shape. In fact, the largest disagreement since the early 20th century over the Commons and the Lords was the Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005 (Russell & Sciara 2007).

With these reforms, it now means that no party in the Lords can dominate. There are several groups in the House of Lords which include Conservative peers, Labour peers, independent Crossbench MPs, and Liberal Democratic peers – who have since gained better representation in the House of Lords (Russell & Sciara 2007).

Reform

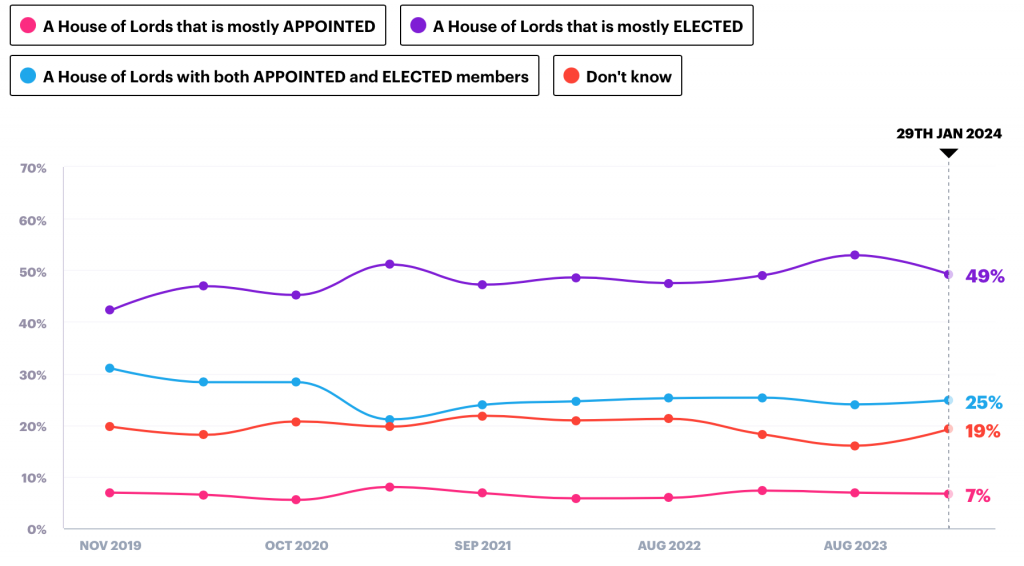

Figure 1 shows, in particular, the clear support for a mostly elected House of Lords amongst the public. It also shows the lack of support for the status quo, with only 7% of people supporting a wholly appointed House of Lords. It is important, however, to delve deeper into the reforms that have been suggested.

A report by the Lord Speaker, Lord Fowler, was released in October 2017 suggested the reduction in members of the Lords – that it should be capped at 600. To do this, there would have to be a “two-out, one-in” approach (Kelly 2023: 9), allowing for the reduction in members to 600. Once completed, it was then suggested that appointments should be limited to the number of vacancies arriving, thus keeping that 600 person membership (Kelly 2023). It was also suggested that members should serve a 15 year term that could not be renewed. Importantly, many of these changes may not require legislation, simply commitment and convention by the government.

It is important to note that the House of Lords were critical of Boris Johnson compared to Theresa May, who seemed to show no restraint in appointing peerages to the House of Lords and appointed Evgeny Lebedev, whom the Security Services showed discontent about (Kelly 2023). Professor Meg Russel also blogged discontent, particularly noting the problem that there are no formal restraints on Prime Ministers handing out peerages, and strikingly and most problematic, that there is a “lack of rational basis for its party balance [of these appointments]” (Kelly 2023: 12).

Another, much more radical report was released by the Labour Party. It was named ‘A New Britain: Renewing Democracy and Rebuilding our Economy’. It was lead by Former Prime Minister Gordon Brown (Kelly 2023). It argued for a democratically legitimate upper chamber and that it is “indefensible” that there is still an unelected House of Lords in this day and age (Kelly 2023). It thus supported replacing the House of Lords with an ‘Assembly of the Nations and Regions’, which purpose would be to safeguard the constitution of the United Kingdom, where its powers would be limited to a range of constitutional issues, that would be first consulted on, and tied to the Supreme Court (Kelly 2023).

There is general convention, commented by William Gladstone, that in the parliamentary process it must be assumed that people will act in ‘good faith’ and have ‘good sense’ (Wheeler-Booth 2001) the in those that work in it. Scholars writing in 2001, namely Michael Wheeler-Booth, concluded that it remains to be seen whether the ancient procedures of the House of Lords will remain, but also explained the prospect that parties may control both Houses of Parliament, and not just one (Wheeler-Booth 2001). This is an important point – what would it entail for the British constitution, if the party system is more pronounced in the House of Lords – will there be proper scrutiny of legislation?

Many of the reforms that have been highlighted in this blog steer well away from a party majority system in the Lords. Some, such as the Labour report, provide an outlet for discussion on representing the regions and devolved nations of the UK, while other reforms control the membership and composition of the Lords and look to reduce its size.

The arching point remains. Polling suggests that the public wish for an elected House of Lords, that the political climate in modern British politics, and contemporary politics in Western nations as a whole, much prefer democratic legitimacy. If that legitimacy in the Lords cannot be obtained, then the point in the Lords may become futile. Radical reforms or dissolution of the Lords will eventually change that. The pressing question is: can we ensure non-partisan scrutiny of government legislation and their actions with a democratic house? Or will we end up with two houses, with a party majority, that can do as it may – is that really democratic?

Bibliography

Kelly, R., 2023. House of Lords Reform in the 2019 Parliament, London: House of Commons Library.

Russell, M. & Sciara, M., 2007. Why Does the Government get Defeated in the House of Lords?: The Lords, the Party System and British Politics. British Politics, Volume 2, pp. 299-322.

Wheeler-Booth, M., 2001. Procedure: A Case Study of the House of Lords. Journal of Legislative Studies, 7(1), pp. 77-92.

The author has demonstrated key understanding of the topic area, utilising it to set the stage for their introduction. While the article is titled ‘What is the point of the Lords’, it has not addressed the primary function of the Lords, such as their scrutiny role of Parliamentary bills. This may have been useful for context when explaining with the HOL was critical of Boris Johnson. The author has displayed critical analysis in regard to renewing democracy, namely the replacement of a HOL with an Assembly of the Nations and Regions, due to the overall desire for an elected HOL to encourage democratic legitimacy or the process of reduction of members and hereditary peers. In summary, the author has addressed many examples of the HOL in regards to reform in recent years, explaining the recent function of the HOL demonstrating key understanding. However, I believe it may have been useful to address the role and primary functions, in order to use examples as supporting information when describing what the role or point, of the House of Lords is

The author demonstrates clearly extensive knowledge of the United Kingdoms Upper chamber, the House of Lords (HoL). This knowledge is exemplified through the acknowledgement of the reductions to membership in the HoL and its historically makeup. The author precedes to discuss potential reforms to the HoL including a ‘’reduction in members to 600’’ which was recommended by Lord Speaker, Lord Fowler. The two examples chosen of potential reform are excellent as they are headed by Lord Fowler who has a plethora of knowledge of the interior workings of the HoL due to his time as Lord Speaker. While the other example is heading by former PM Gordon Brown, who would have had substantial experience in dealing with the HoL. These factors make these examples very commendable. While this Blog post is very well written and researched, it could have been beneficial to comment on any positives of the current model of the HoL. For Example the expertise which appointments can offer, this paired with the fact that the HoL provides a secondary filter of scrutiny for Parliamentary Bills, which is a wholly positive factor.