If the future of work involves effective AI use; how can we prepare students to perform at critical levels? The longstanding politically conservative argument is that colleges and universities fail to provide students with critical thinking skills; instead, they argue that higher education institutions provide students with skills to ‘critically observe‘ and follow a mold. This thinking has deep roots in critical feminist, queer, and decolonial networks.

If students are prohibited from engaging with AI in their assessments, they miss critical opportunities to be assessed on their AI skills. How can they demonstrate that they can effectively engage or use AI for writing, research, professional/self-development or otherwise, if the academy says that they cannot be assessed on their AI-use? Formative and summative assessments are designed to track students’ progress, ensure that they are performing aligned with pre-set expectations, and that they are ‘future ready’. In what universe is a student prepared for ‘future ready’ if they are instructed to not use AI, not assessed on AI use, prohibited from demonstrating to their tutors a high degree of AI proficiency and readiness, and if they are trained to fear AI altogether?

This is counterintuitive. Universities have a legal and moral obligation to students and taxpayers. If AI is the future of work (and the world) – statistics from Microsoft (US) suggest that “75% of knowledge workers use AI at work today” – then educators’ failure to incorporate AI in assessment is dereliction of duty. (It is worth noting that, according to McKinsey, “48% of employees rank training as the most important factor for Gen AI adoption”.)

Academia is losing. By some academics’ definition, AI is acceptable everywhere except the classroom, the lab, and the library. In those individuals’ vision, admissions departments, student support units, and administrative units would all be entitled to use AI to direct an institution’s daily operations, including the operational impact that academics and their scholars rely on; however, the institution’s scholars would be wholly prohibited from engaging with AI altogether.

Effectively navigating a complex set of theories and engaging with philosophical concepts, designing PowerPoint presentations, and producing a set of flash cards with AI all require a high competence in prompting and interactivity with machines. If we accept that AI is now a permanent tool of public and private sector operations, surely academics appreciate that prompting is itself a skill beyond copy/paste? Good prompting is not dissimilar from navigating a library, a data archive, or even a dialogue with an academic mentor. The idea that the academy should dig its heels in and reject a tool that has already transformed global society is remarkably dumbfounded, unethical, and seriously irresponsible.

That said, some academics have begun to soften their stance on the use of AI for certain purposes, such as by ESL scholars for translation assistance – which is an accessibility accommodation. However, one must ask about support and accommodations for their other pupils: the dyslexic, neurodivergent, disabled, and students from nontraditional backgrounds.

Many of those nontraditional and neurodivergent learners will find themselves beneficiaries of the cognitive offloading and scaffolding that machines provide today; uses which require solid prompt engineering and AI literacy skills, which can further aid learners in their own thinking, and introduce a new level of interactivity and reflectivity to learners’ scholarship. Academics’ failure to acknowledge this reveals a deep gap between the academy and its scholar community; as well as between institutions and the communities they serve at-large. Developing a method to assess this use is vital to produce thinkers, workers, and social contributors of tomorrow.

One of the arguments that many academics now make is a defense rooted in the concept of ‘academic freedom’; the very notion which has long been used against Black and Indigenous people of color and women in the academy. Historically, for example, Black academics have had their Black Studies or Africana Studies departments decimated and dismissed altogether whilst their theories or ideas are extensively coopted by their history, sociology, and political science peers. (This point was raised by Professor Christine Sharpe.) These Black academics’ ‘freedom’ has long been ignored or violated altogether. However, scholars and learners’ freedom to develop in a world in which digital tools, technological literacy, and machine learning is ridiculed as a violation of integrity. Whose integrity? There is, indeed, an argument to be had about teaching students and learners to think – to develop their own ideas and to explore and criticize the world – to teach students the skills to measure, design, and critique – and to theorize (sociologists Patricia Hill Collins and Corey Miles write that all Black people are theorists; and bell hooks laments that theory can be affirming in helping one understand and explain the world). If used effectively – and, most certainly, if taught to use effectively for the purpose of learning and developing – AI can be a valuable tool in helping learners engage with the world and the scholarship around them.

Academics express their frustration with extra work, pastoral care, their own research projects, and family life balance; in classes of 100+ students, academic staff do not have the time of providing bespoke, individualized attention to their fees-paying students. So, why would they oppose their students’ use of AI to further research into their learnings or to act as a bespoke private tutor? A student can be relegated to an overworked private tutor who lacks context in their assignment, interests or needs; or, a student can use an AI agent to support their learning and their curiosity, and act as a learning partner. An AI agent can act and respond to a custom set of prompts, which might include a syllabus, module rubric, key learning outcomes, and students’ desired objectives. Further, considering the reality that many students now work near full-time hours and have less support to pursue higher education– made even worse by inflation and low wages — the reality of an accessible, personal learning helper should bring educators great relief. In the UK, waiting lists for clinical diagnoses for neurodivergent conditions can extend beyond three years; surely educators would be more interested in helping their students effectively learn better, not disadvantage them over fears around machine learning.

Academic speak – academic prose, academic writing, academic publishing – have long been critiqued as tools of Whiteness. Students have long been told that they must sacrifice their mother dialect and their mother tongue in exchange for the acceptance of the academy. The sacrifice was never communicated as a tool for standardization; instead, it was communicated as a tool of subjugation. ‘You must learn to think, theorize, write, and speak in this way in order to be deemed acceptable,’ is what the academy has told scholars. Code-switching becomes forced code-speak. What about those individuals who see their roles and their future in their community? Imagine a universe whereby scholars – competent, experienced in both the academy and the workforce – use machine learning (as experts of the machine) to refine their speak in the form that the academy has demanded. Where is their academic ‘freedom’? Where is the applicability of their skillset for the ‘real world’?

One of the most painful aspects of my academic career to-date (my doctoral journey primarily) is rooted in the sad reality that the academy rejects non-academic speak from scholars but praises it – relishes in it – from social and cultural influencers — those women and men who have carved their way through the academy but never up. Besides that, academics preach of the ‘soul’ that is academic-writing and academic-speak yet ignore the reality that the ‘soul’ they speak of ignores or has violated many of the people they claim to care about.

The academy never viewed them as human; and, yet demands they write or speak in a language that is foreign to them and their community and their goals. The academy demands that their theories and their conceptualizations of the world be delegitimized in order to gain acceptance – and, yet, it never reflects internally to shift or change itself. The system within the system can critique the system but never itself; all views are illegitimate except for its own – the terms academic ‘freedom’ and literacy apply only to the academy’s definitions; Innovation or theory be-damned.

But, where does that leave us?

More hyperbole surrounding concerns about environmental impact? If departments are going to take sharp approaches against AI-use on the basis of environmental concerns, surely they will also begin to curtail their carbon footprint (international student recruitment and admissions; international flights to conferences; staff investment plans in fossil fuel industries)? Long distance academic conferences are both costly and leave a significant carbon footprint; especially, when virtual engagements can be as effective (if not more effective) than in-person conference engagements.

More hyperbole related to critical thinking? Despite the short-term studies whose preliminary findings have been released much to the pleasure of anti-AI academics, effective AI-use enhances critical thinking and makes the classroom and learning experience more accessible and inclusive. (See below resources for further reading on this.)

Machine learning (including Gen AI) are here to stay. We have a moral obligation to teach with purpose and a solemn duty of care to students, colleagues, local communities, and society at large to ensure that our students are AI literate and confident. Academics must not allow personal prejudices to dictate their commitment to educating and preparing their learners for the future of work and full participation in society. Improved accessibility, significant cost-benefits, renewed excitement and interactivity in the classroom, and practical skills to perform in society are just a few of the benefits that AI brings to learning.

Perhaps a solution is for government to develop AI literacy mandates in exchange for funding or research grants. As public and private sector decision makers begin to implement more machine-led automation into their operations, so too will taxpayers begin to expect the same of our academic institutions. This is a vital opportunity for faculty to partner with a transformative tool; a soon-to-be trillion-dollar industry that is projected to have a massive net-positive impact on communities around the world.

Further info for educators:

- An academic, Tom van Woensel at Technische Universiteit Eindhoven released a very comprehensive “White Paper on AI and Education“. You can read that [here].

- Russell Group Principles on Generative AI in Education. Accessible [here].

- HEPI Report: AI and the Future of Universities. “[higher] education’s role is not merely to adapt to AI, but to leverage it as a catalyst for cultivating uniquely human capabilities – critical thinking, creativity, emotional intelligence, metacognition (the ability to understand and regulate one’s own thinking) and contextual adaptation.” Accessible [here].

- American Historical Association Guiding Principles on AI Use in Higher Education (includes a table resource and a template for AI-use considerations with colleagues and students). Accessible [here].

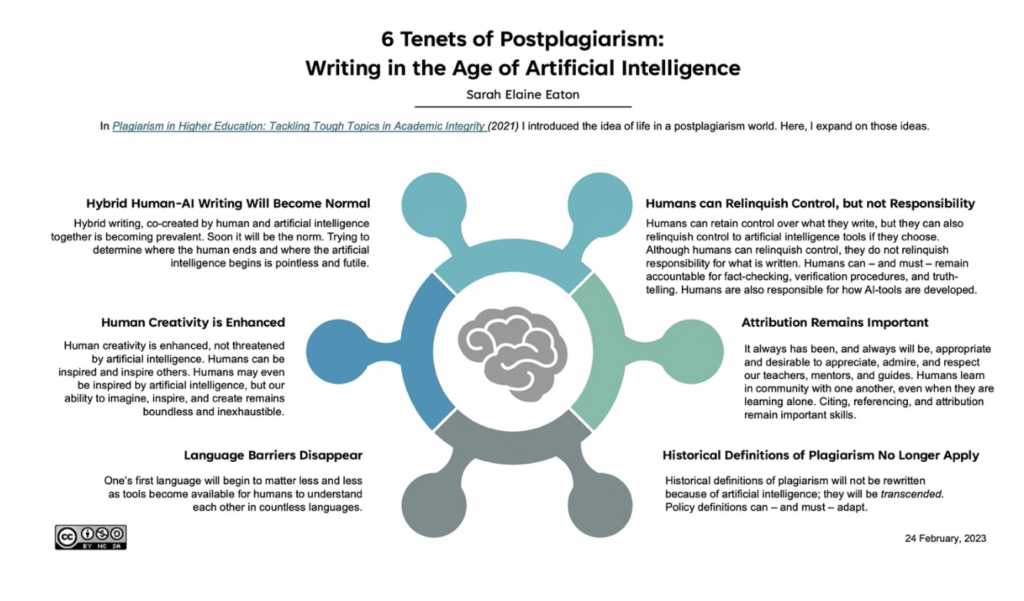

- Eaton, S.E. (2023). Six Tenets of Postplagiarism: Writing in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. University of Calgary.