By Jamie Nugent, PhD Candidate in History

In the aftermath of the Bristol protests against the Conservative government’s new Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, the Bristol Mayor Marvin Rees pinned the blame for the violence on what he called “revolutionary tourists” or “protest tourists” who had come in from the outside itching for a fight. Regardless of the truth of his claims, it is interesting to note how common this claim has become in an era of global mobilities and ever-more global protests. It has more of a whiff of the claim of “outside agitation” used since the 19th century to contrast ‘respectable’ locals with ‘troublesome’ outsiders. It also shows a shifting landscape in the meaning of protest itself – especially as authoritarian governments and even democratic states clamp down on street-based forms of expression as well as freedom of speech online.

In 2019 the blogger and Experiences Ambassador for AirBnB, Sebastian Nieto Milevcic, explored the concept of “Protest Tourism” in the context of the Chilean ‘Estallido Social’ (Social Outbreak) which erupted in response to corruption, privatisation, and widespread inequality in the South American nation. Milevcic noticed that the protestors were accompanied by a number of “mere observers, blog enthusiasts, and selfie explorers,” including Americans and Europeans who stood out from the crowd. He asked them why they were there, and they gave several responses:

“I wanted to see something real.”

”I just want to tell my friends I was here.”

“I was just too curious to watch what was going to happen.”

Milevcic mused as to whether this was ‘Dark Tourism’, which draws millions to Chernobyl, Fukushima and Ground Zero in Manhattan, as well as genocide sites such as Rwanda and Cambodia’s Killing Fields. He concludes “maybe it’s just Travel itself that is innately voyeuristic?” Although Milevcic’s observers were just that, observers, the distinction can often be blurred in a digital age where the camera and microphone can be effective weapons – both for and against injustice. As for voyeurism, Nick Cohen in The Guardian castigated “Radical tourists” who “trawl the world for revolutions to praise” as “no better than sex tourists” in search of exotic thrills they cannot get at home.

“Pleasures sated, the tourists fly away from the poverty and the corruption. The lies they have lived and paid others to live on their behalf don’t bother them,” Cohen wrote. He was referring specifically to supporters of the regime in Venezuela, whose own economic mismanagement and political crisis has led to a mobility crisis of a different kind, with over four million estimated to have left the country since 1999.

Though it might be called ‘voyeurism’, the practice of ‘outside interference’ in domestic or local disputes has a long history loosely connected to espionage or power politics. Take for example the poet Lord Byron, who went voluntarily to fight in the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire; or the scores of British (and Irish) volunteers who fought against Franco’s Falangists during the Spanish Civil War, not least George Orwell and the trade unionist Hans Beimler. Or with non-violent protests, take the example of Viola Liuzzo and James Reeb, white Americans who travelled from their homes in California and Kansas, respectively, in order to attend the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery (dramatised in the 2014 film Selma). Both Liuzzo and Reeb lost their lives during the marches.

Mobile protestors can often be the tool of, or victims of, international events and political manoeuvres. Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior, a commercial trawler which travelled around the world protesting against whaling, seal-hunting and nuclear tests, was infamously sunk by French agents near New Zealand as it was setting out to protest nuclear testing in French Polynesia. Just before the Soviet Union invaded and occupied the Baltic States in 1939, demonstrators appeared in major cities on 18 July calling for incorporation into the Soviet Union, and under the threat of Soviet invasion, this call was swiftly followed by the national parliaments of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia applying for membership and being annexed. A similar tactic is suspected in the eastern part of the Ukraine which has seceded – so-called “protest tourists” from Russia are often seen at rallies in Donetsk.

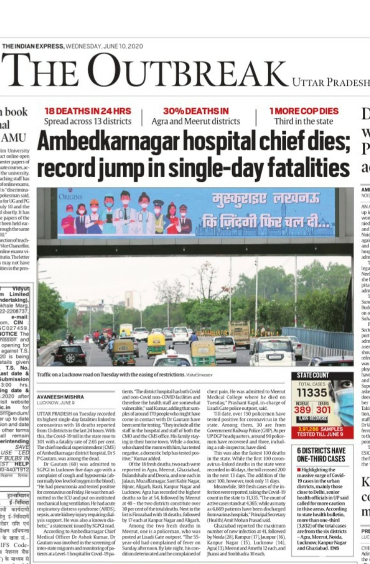

Such actors, whether in military conflicts or political issues, often receive short shrift from the powers-that-be. Alan Shatter, Irish Minister for Justice in 2011 accused members of the anti-gas group ‘Sea to Shell’ of being “self indulgent protest tourists,” much like Mayor Marvin Rees has accused the Bristol rioters. With the ever-increasing concerns to contain COVID-19, and public demonstrations in the firing line of public health restrictions on travel and assembly, it is impossible to say what impact the pandemic will have on “protest mobilities,” as I coin it.

Research suggests that there was “no evidence” of a spike in infections after the Black Lives Matter Protests in the US last summer. But YouGov polling suggests that the UK public emphatically support almost every public control measure (such as water cannon, tear gas and plastic bullets) except live ammunition. In a world of new, uncertain threats and an ongoing crisis of legitimacy in democratic nations, it can be expected that clampdowns on mobility (as seen during the pandemic) and public demonstrations (as seen with the new Bill) will be pursued by governments unable to admit that the situation is far from under control.