The delight of stepping into a warm bath after a long, busy day. A sense of intense relaxation. Do all migrants feel like that when they open a book written in their own language? Words and phrases so familiar, echoes of childhood: ‘kloddertjes’, ‘klontjes’, ‘een spookachtig moment’.

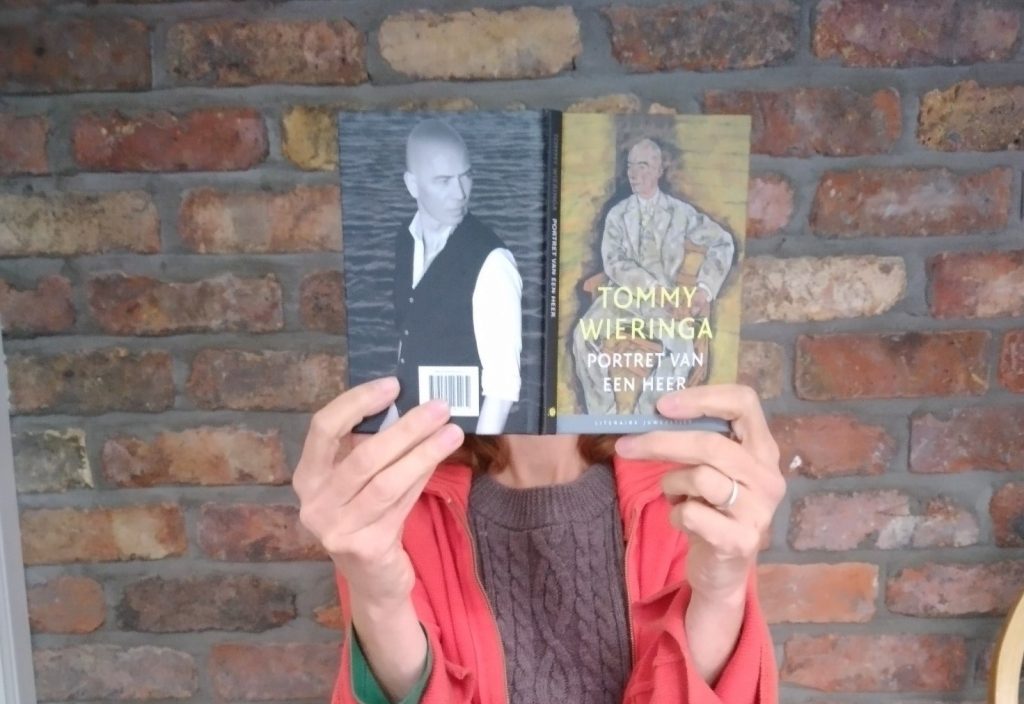

I hardly ever read Dutch literature these days, but find Portret van een heer (Portrait of a Gentleman), hidden behind another book on a top shelf in my office at home. Forgotten, dusty, waiting to be read. I grab it and study its design. The back cover presents a black-and-white picture of the author Tommy Wieringa. He looks over his left shoulder into the distance, a waterscape behind him. When I stretch the book far open, his painted likeness on the front cover stares at his photographed self.

But wait a minute, I recognise the style of the portrait. I’m sure, it must be by the Austrian artist Egon Schiele. I recently explored his life history when writing a chapter on a museum in Český Krumlov, the Egon Schiele Art Centrum, (Svašek 2019). I remember reading that Schiele died in 1918 of the Spanish Flu. As the Coronavirus pandemic was still ahead of us, I did not pay much attention to the cause of his death. But one thing is clear: the person depicted in the painting is not Tommy Wieringa, who is Dutch and was born in 1967.

Curious, I open the book and soon discover that the uncanny resemblance of writer and painter is the main focus of the first story. In the story, Wieringa recalls how he first learnt about the portrait when a friend, who had seen it displayed in Museum Belvedere in Vienna, sent him a postcard of the work, describing his encounter with an Austrian ‘Wieringa’ as ‘beangstigend’ (frightening). The author himself was also shocked, seeing his mirror image. ‘Zelfs het puntje op zijn schedel was identiek!’ (even the pointed shape of his skull was identical).

In the rest of the story, the Dutch author writes about his journey to Austria and the Czech Republic, in search for the man in the portrait. The model turns out to be Victor Ritter von Bauer, a once wealthy landowner who was born in 1876 and inherited many acres of land and a lucrative sugar refinery from his ancestors. He was an energetic aristocrat, one of the first Austrians to fly a plane and a keen traveller who wrote about his travels to the Pacific in Eine Reise auf der Insel Sawaii. After the break-up of the Habsburg Empire in 1918, he lost most of his properties due to land reforms and Masaryk’s nationalisation policy. He died in 1939 and was buried in the chapel near Kunín Palace, an impressive eighteenth century baroque building still in his ownership at the time of his death.

In Portret van een heer, Wieringa visits the Palace, today a museum. Tellingly, he is welcomed by a soft-spoken caretaker who, in awe of Wieringa’s familiar physique, welcomes him with the solemn words: ‘the lord of the castle has returned’.

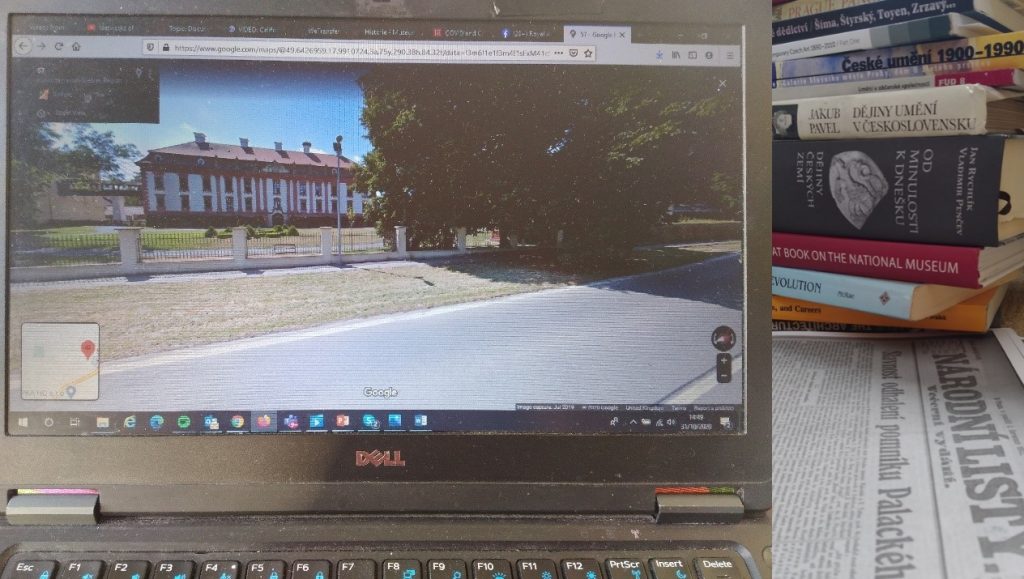

Unable to travel to the Czech Republic, I find Kunín Palace after I’ve landed the tiny dangling Google figure on the digital map. I do this a lot, these days of lockdown, grabbing the little person by her collar and dropping her to either start an adventure, or investigate some local details for my research. So, I’m in – a few virtual steps, and there it is. Indeed impressive.

I also visit the Palace’s website, and read about its history, it was built in Habsburg times. This reminds me of that pile of research materials in the corner of my office: numerous books and copies of nineteen-century newspapers that I made in historical archives in Prague last year. One of the newspapers is Národní Listy, a Czech nationalist daily newspaper that propagated Czech cultural revival. One is from 1 July 1912, and reports the unveiling of a monument in Prague, a huge statue of the historian and political thinker František Palacký. Palacký’s vision of Czech nationhood inspired generations of nineteenth and twentieth century artists and intellectuals. He is often called ‘the father of the nation’.

I wonder what Victor Ritter von Bauer would have thought about Palacký’s revolutionary ideas. In Portret van een Heer, I read that toward the end of his life, von Bauer gave lectures in Vienna, London and Paris about history and politics, and published Zentraleuropa: Ein lebendiger Organismus in 1936. In the book, he reflects on the cultural histories of Central European nations, and the title refers to the region as ‘a lively organism’. I should try to get my hands on the book.

So here we go, unexpectedly the Dutch travel story has taken me back to work, just when Reading week ends.