Out of the ruins

DIVIDED, WAR-WEARY communities; deaths of innocents; the psychological trauma of living with bomb attacks, security checkpoints and constant foreign military presence: the citiesof Belfast and Nicosia share a bleak history of civil conflict. Yet it is just such parallels that are now sparking an extraordinary experiment in creative imagination and hope, that aims to build a more positive future for the Cyprus capital.

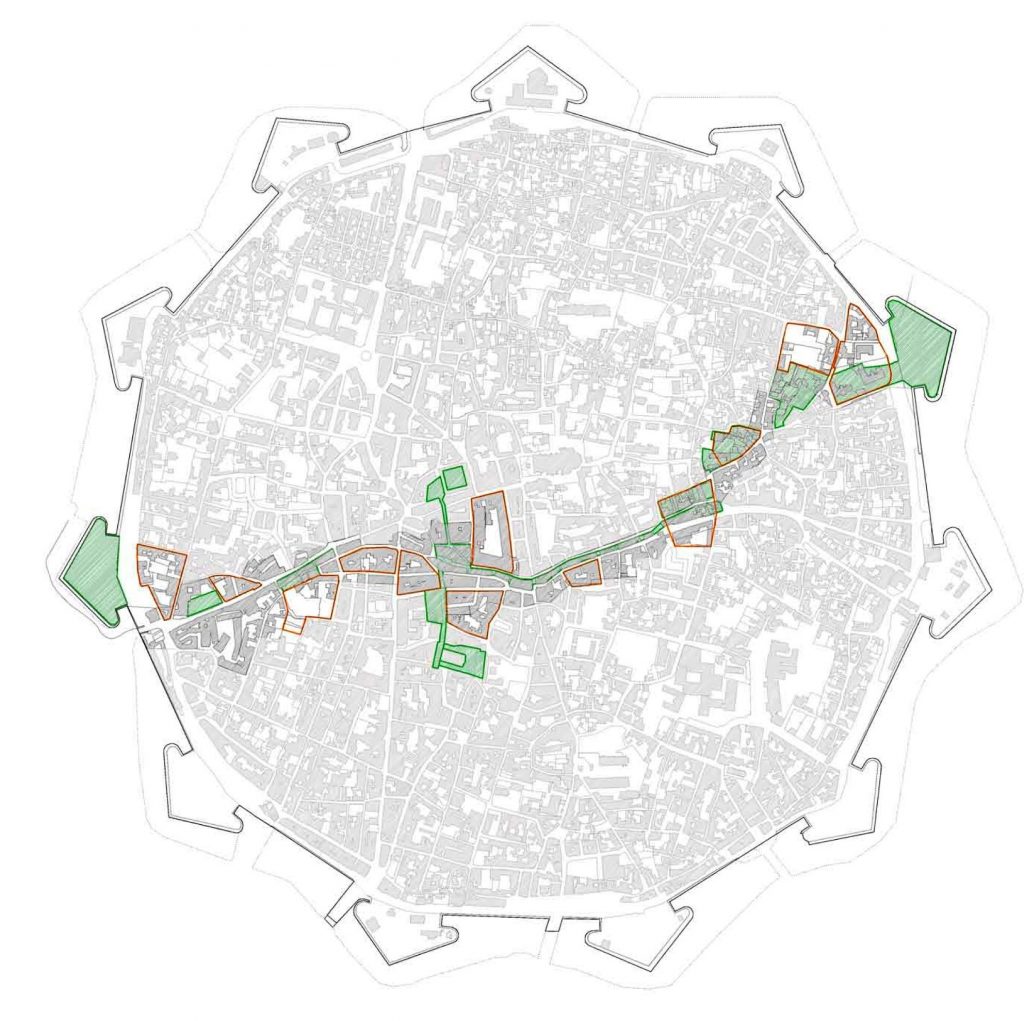

Fault line: Nicosia’s buffer zone inside the old walled city

Twelve architectural students from Queen’s University Belfast have been working on a visionary design project for Nicosia, looking at how architecture and planning can help to ‘glue’ together communities divided for more than thirty years. The students’ designs are for imaginary buildings; but their ideas – and their idealism – are helping the city to reshape its political and psychological landscape.

In 1974, following years of inter-communal violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, a permanent ceasefire partitioned the Republic of Cyprus into two geographical areas: the southern part inhabited by the Greek Cypriot community and the northern third of the island occupied by Turkish Cypriots. The ‘Green Line’ separating the two split the island from east to west, a meandering division that also cut through the heart of the old walled city of Nicosia. Twenty thousand Greek and Turkish Cypriots were displaced in addition to the thousands killed in the preceding conflict; an impenetrable buffer zone, administered by the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), has kept the Green Line in place, freezing the conflict without ever resolving it.

Dr Karim Hadjri, a senior lecturer in the School of Planning, Architecture and Civil Engineering at Queen’s and a former resident of Cyprus, set the design project for twelve of his final-year architectural students. He explains:

“Nicosia was selected by us because of its ongoing physical division and similarities with Belfast. It is referred to as the ‘last divided city in Europe’. We felt that our students, due to their background and experience of division in Northern Ireland, would relate to the local issues and could offer bi-communal and integrated solutions through architecture.”

The cross-cultural theme is reflected in the team’s backgrounds and life experiences: except for one Canadian, the group is a fairly even mix of students from Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, and the project is being run in conjunction with a Greek Cypriot and a Turkish Cypriot lecturer from universities in Cyprus.

In an unusual move, the Queen’s students were allowed access to the buffer zone by the UNFICYP, placing them amongst only a handful of people (mostly diplomats) who have been admitted since the zone was first sealed. Paul Toal, one of the Belfast students, wrote of the experience:

Entering the UN-controlled Buffer Zone, sandbags and collapsed ruins are testament to a distant life torn brutally from reality and existence. This place of memories is littered with the remnants of everyday life, dust and dense vegetation … Although life is gone, I was being watched – by two armies. The abandoned houses, shops and streets that once formed the backdrop for social activity now portray a theatre of death and decay.

The imaginary projects are focused on the buffer zone within the old walled city of Nicosia, a ring of eleven bastions joined by 16th-century Venetian walls. This part of the buffer zone ranges from 50m wide to a mere 4m in some places, and is only navigable at one north-south checkpoint.

Dr Hadjri describes the existing buildings – which include neoclassical, Turkish Ottoman and Venetian style architecture – as of historic value. He stresses the importance of preserving the ruins with repairs or extensions in a sustainable and appropriate fashion.

He explains: “We are not interfering with the footprint of the Buffer Zone – if everything were to be started from scratch it would give a false impression. The students are designing a diverse range of schemes, all neutral buildings, to prevent either side being able to say ‘That’s mine’. The project is truly about bringing communities together; gluing not just north and south but creating a linear link along the promenade.”

The projects are impressive in their scope, and sensitive to the city’s social and physical contexts: designs range from civic buildings, to educational buildings, to community centres. Many of the projects focus on drawing the two communities together through shared interests, such as dramatic and visual art, sports and crafts, often drawing on their sensitive location for creative energy. Others – a National Archive, and a National ‘Theatre of Memory’ – focus on honest documentation of the past as a way to build a united future; bi-communal education of young people is stressed heavily, with designs for an integrated primary school and a Language and Cultural Centre. Often the main need seems to be for a community meeting place and forum for dialogue, however difficult that dialogue may prove.

The final two projects address more immediate concerns: a Thalassaemia Treatment and Research Centre to focus on the genetic disease that affects 16% of the Cypriot population – of both Greek and Turkish ethnicity; and an Academy for Applied Environmental Research, exploring the island’s shared concerns of water shortage, energy consumption and environmental conservation.

This is the first attempt to turn dreams for the Buffer Zone into buildings, and hopes are high that some of these proposals may one day materialise. The project will conclude in May with an exhibition of all the students’ work in Nicosia, presented to a bi-communal audience of Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots and representatives of the resident UN force.

Grace Boyle