Learn by Doing? More Like, Learn by Failing

SEQUEL* and I agreed that the videos you put together didn’t match the brand aesthetic.

Christopher, Humanity Cosmetics CEO * PR Company

Practitioners and intelligentsia often claim that mistakes can be regarded as “a learning opportunity”. However, this maxim has not always proven obvious to me. Quite the perfectionist, I want my work to be the best it can be by taking constructive criticism into account. So how was I to respond when Humanity Cosmetics (HC) informed me that they did not approve of my first social media content batch for them?

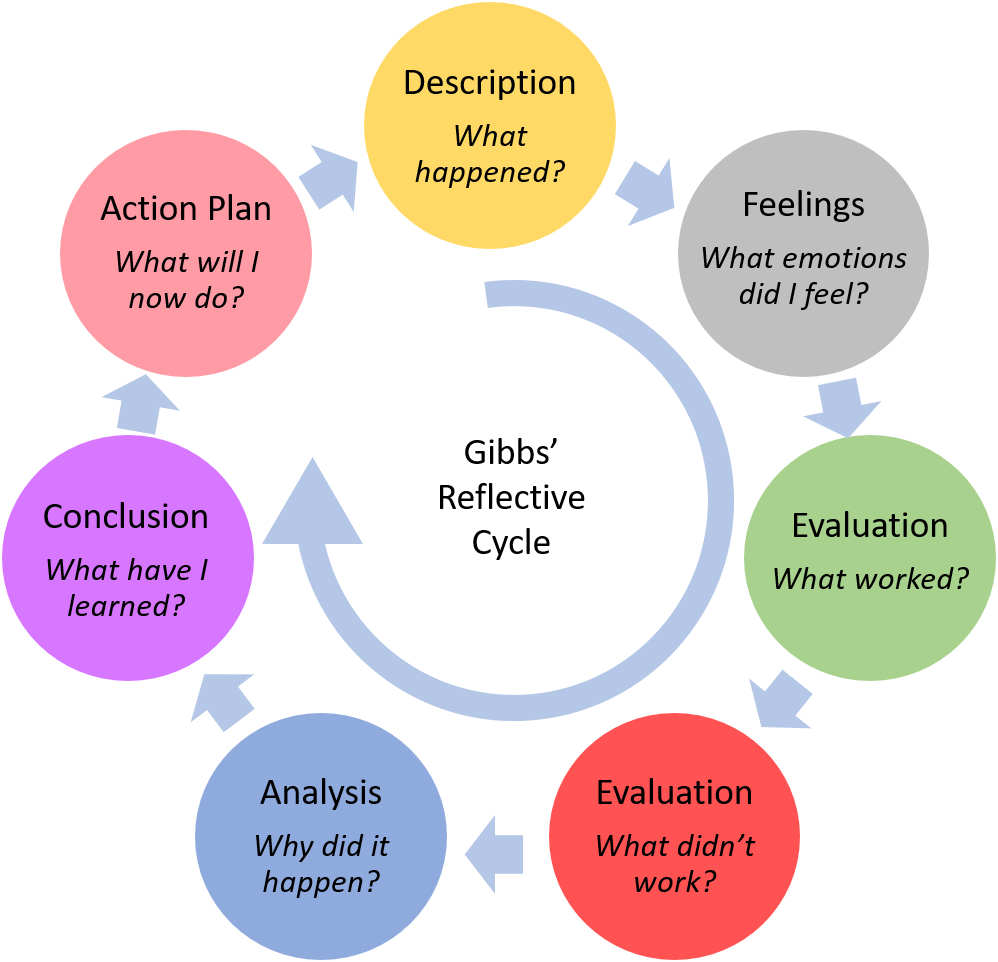

My third and final blog post continues using the six-step Gibbs’ reflective cycle (1988, p. 49), as taught in my Work-based Learning module, to critically analyse and evaluate my work placement performance.

Trials & Tribulations

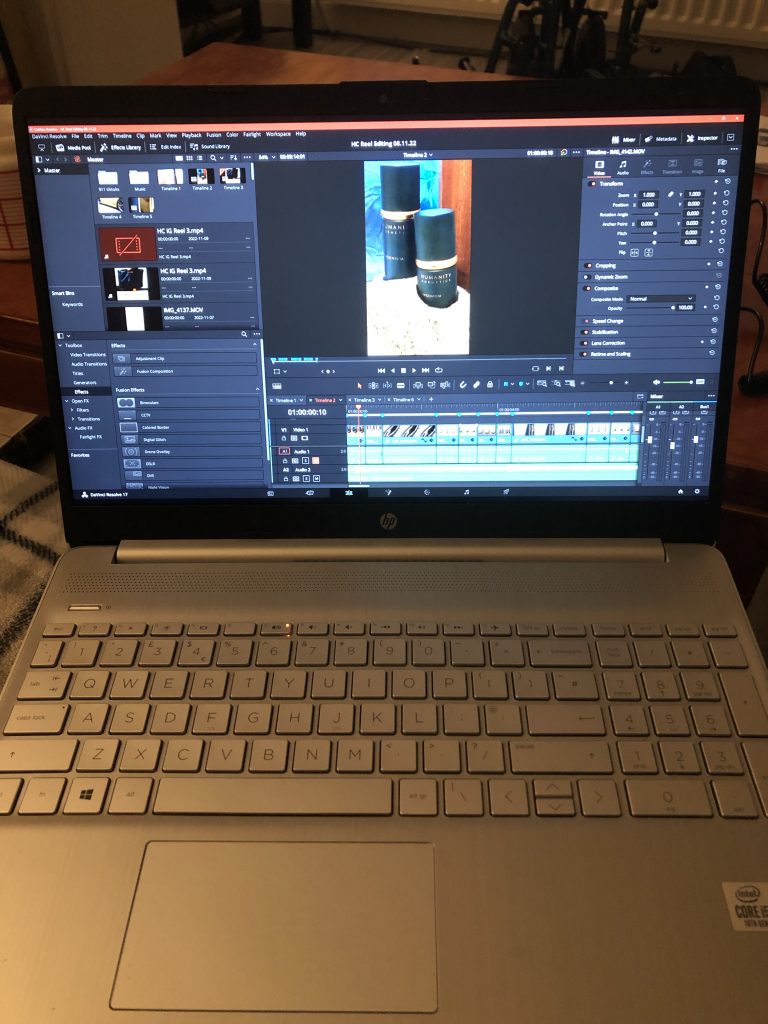

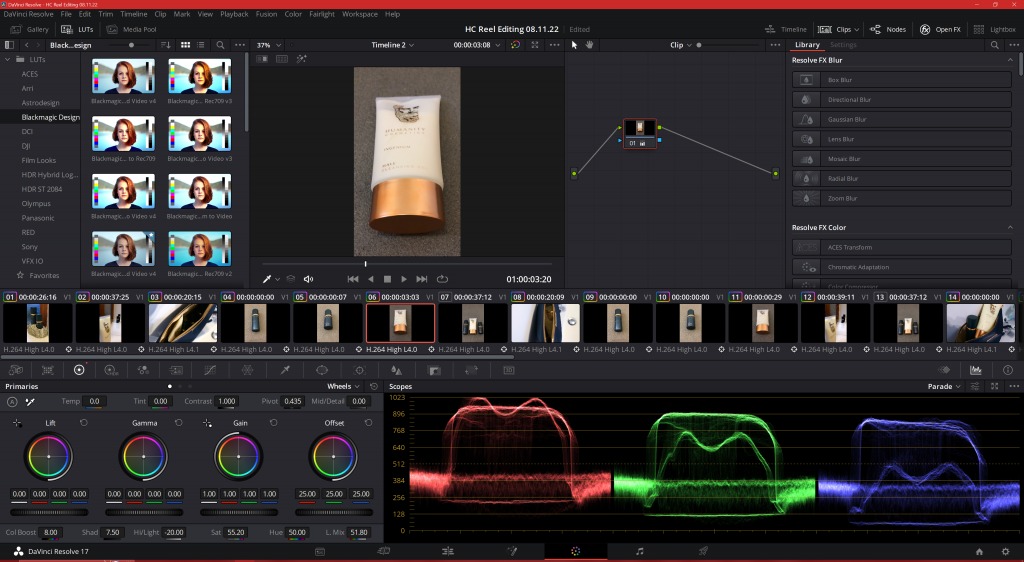

In early December, Teams feedback was received from HC concerning the first content batch produced for the company. The minute-long videos mostly consisted of posing and filming HC products in ways seen in skincare advertisements (but without a studio setting), before cutting footage together with music. In short, HC simply could not accept the content for use online. It was criticised as cheap-looking and did not match the brand aesthetic of luxury and masculinity. Fortunately, HC provided good advice on how to amend future productions. Efforts were to be refocused towards shorter duration TikTok content, better suiting production value limitations, with music evoking a more epic sense of awe and luxury.

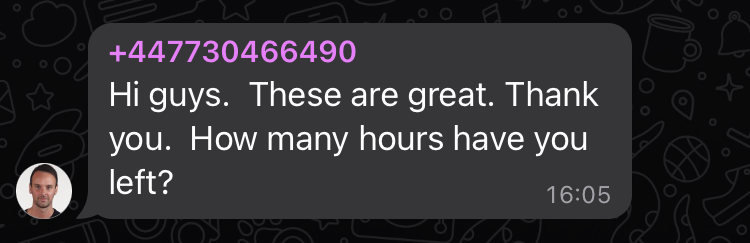

Prior to the Teams meeting occurring, I was informed in a WhatsApp text had the first content been rejected. This invoked feelings of dejection, with a nagging sense that the HC work placement was perhaps out of my depth. Initially, there was some confusion as to what had gone wrong. I couldn’t help but wonder if HC maybe regretted recruiting three inexperienced film students. However, as the meeting progressed, new advice brought insight for improving future content and matching the brand aesthetic. This temporarily eased the stress factor. Nevertheless, some nervousness and anxiety remained until the more positive feedback was received for the second content batch.

Between going into the meeting, and the subsequent changes to my future HC content, this period had both its positives and negatives. Nobody wants or likes their work being rejected. For me, this induced stress in needing to quickly fix the issues that had the potential to threaten the whole placement. Jasper (2013, p. 108) states that “initially, entering work … as a student can be very daunting” so experiencing anxiety is to be expected. To accommodate for our limitations as students, e.g., reliance on student housing for sets, HC accepted that the content looked cheap because it had been made on the cheap. This allowed a new focus on shorter duration content on the better-suited TikTok platform. Originally, before production began, HC had its interns research their branding aesthetics, those of competitors, and how male lifestyle influencers marketed the products. While I thought this groundwork went well at the time, it became apparent that more research would have laid stronger foundations for the video production. According to Beach and Vyas (1998, cited in Griffiths and Guile, 2001, p. 118-119), “students need to learn in ways different to those in which they learn in school or college.” My time with HC has resulted in real-world experiences beneficial to rectifying the mistakes of the first batch. Overall, my early content was received negatively, but the experience set me up to do a much better job for the next deadline.

There is more to analyse regarding the learning process between the first and second batches. Summarising Kolb and Fry’s (1975, p. 33) experiential learning model, my first-hand participation in and reflection on what occurred provided knowledge of improvement for future efforts. Retrospectively, the first batch can be viewed as a test shoot and edit. Then, for the second batch, applying the feedback with my practiced knowledge allowed for improved results through shortening and better pacing. Akin to pre-production, researching the brand should perhaps be treated with more intensity, as in hindsight, it provides vital understanding for content aesthetics. Additionally, Murakami et al. (2008, p. 17) describe “learning as a change process”, showing how one failure serves the overall learning process in a work placement. Generally-speaking, my responses to the early failure were effective, as evidenced by the HC acceptance of the lately produced content.

Conclusions

Each stage of the Gibbs’ cycle shaped a renewed appreciation of my capabilities, specifically in relation to how I interpret employer demands. The first content batch did not meet client expectations due to a fuzzy understanding of how to produce what was actually wanted. After further consultation with HC, key changes were made to future content. Moreover, a better understanding of what was required to meet the HC brand aesthetic could have avoided the issues of the first batch. Also, stronger brand research and better communication with the client beforehand could have minimised the risk of misunderstanding. However, despite some mistakes, my skills and knowledge regarding the video production process for online platforms certainly has received enhancement through the opportunity to learn.

After all, Candy et al. (2005, p. 101) define ‘learning to learn’ as subconsciously attributing meaning learnt from different encounters across life, then consciously reviewing them. My HC experiences have exemplified some of the challenges I can expect with future remote-working content creation. The initial problems resulted from a lack of understanding of what was wanted, and how to use the resources on hand to fulfil the employer’s requirements. Since further clarification, I have learned from my mistakes, recycling the original longer videos into ones more befitting of the HC-branded luxury model. A more careful approach to researching a brand and its rivals, coupled with a better comprehension of the marketing strategies behind them, will also be a benefit. If I ever find myself in a content creator role again, I now know what to do differently in producing more suitable client-focussed results.

Bibliography

Beach, K. and Vyas, S. (1998) Light Pickles and Heavy Mustard: Horizontal Development among Students Negotiating How to Learn in a Production Activity, paper presented at the Fourth Conference of the International Society for Cultural research and Activity Theory, University of Aarhus, Denmark.

Candy, P., Harri-Augstein, S. and Thomas, L. (2005) ‘Reflection and the Self-organised Learner: A Model of Learning Conversations,’ in David Boud, Rosemary Keogh, and David Walker (eds.), Reflection: Turning Experience Into Learning, London: Routledge Falmer, pp. 100-116.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Oxford: Oxford Polytechnic.

Griffiths, T. and Guile, D. (2001) ‘Learning Through Work Experience’ Journal of Education and Work, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 113-131.

Jasper, M. (2013) Beginning Reflective Practice. Melbourne & London: Cengage Learning.

Kolb, D. and Fry, R. (1975) ‘Towards an Applied Theory of Experiential Learning,’ in C. Cooper (ed.), Theories of Group Processes, New York City: John Wiley & Sons pp. 33-57.

Murakami, K., Murray, L., Sims, D., and Chedzey, K. (2008) ‘Learning on Work Placement: The Narrative Development of Social Competence’ Journal of Adult Development, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 13-24.

Orchestrated Chaos.

You May Also Like

Keep On Keeping On – Bouncing Back From Disappointment

14 April 2023

I Was Just… A Voice.

7 April 2023