PLAN, PRACTICE, PERFORM: SIMULATED JOB INTERVIEWS

“Can you tell us a bit about yourself?”

Fluttering stomachs, sweaty palms, and scattered thoughts are common symptoms experienced by job interview candidates. However, failure to plan and practice dramatically exacerbates such anxiety. Since “interviews are one of the most widely used hiring methods” (Brosy, Bangerter and Mayor 2016: 373), I jumped at the opportunity to put my interview skills to the test during simulated job interviews at university. Interview skills can be of “utmost importance” for university students since many “find such occasions intimidating and unfamiliar” (Walker 1993: 74).

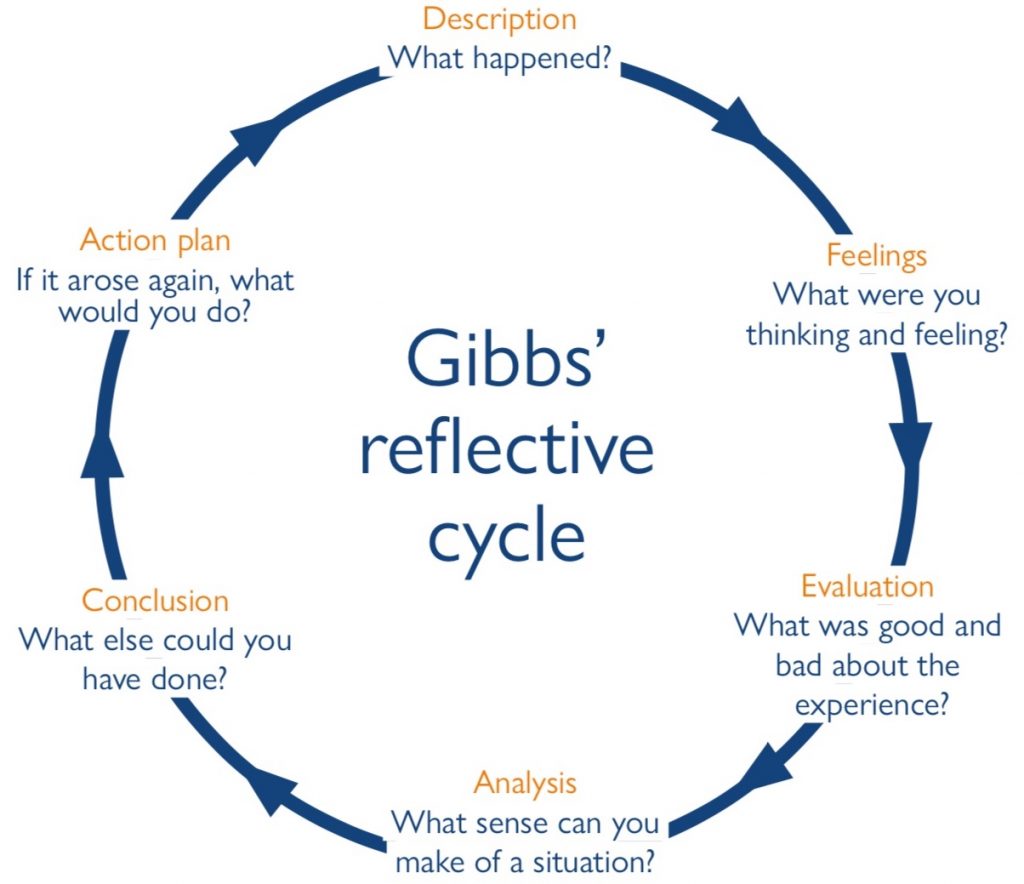

By employing Gibbs’ reflective cycle, this blog post reflects upon my experience as an interviewee during a simulated job interview at university.

Reflection: feat or fiasco?

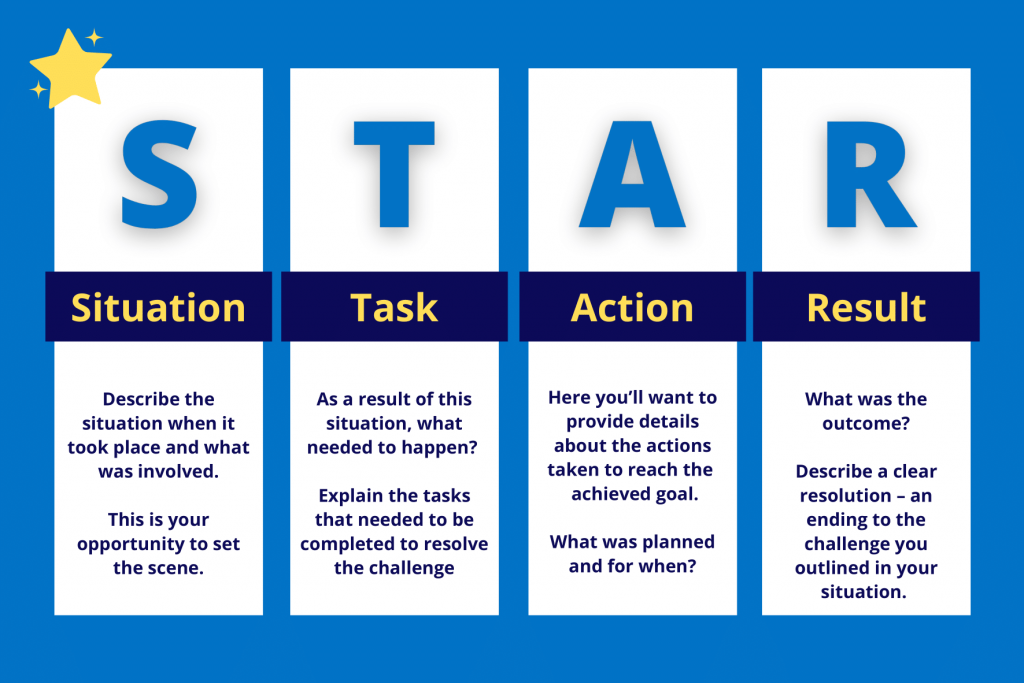

My chosen job description was for a primary school teaching assistant. As an aspiring teacher, I knew that I would greatly “benefit from opportunities to practice communicating [my] skills and abilities as a teacher and colleague” (Juchniewicz 2016: 66). The desired criteria listed in the job description significantly informed my preparation and model answers, alongside the robust STAR technique that is frequently used by job interview candidates.

I have chosen Gibb’s reflective cycle (Gibbs 1988) since it has proven to be “a helpful aid for teaching staff when reflecting on their feelings, thoughts, and actions related to challenging situations” (Markkanen et al. 2020: 46). Unlike other reflective models, “Gibbs adds an emotional dimension” (Husebø and O’Regan 2015: 373), helping to “focus reflective learning” (Markkanen et al. 2020: 46) towards internal feelings as well as external actions. This is particularly relevant for the highly pressurised mental stress of job interviews.

Description:

Before the interview, I tried to recall my model answers. However, adrenaline hindered this and caused me to experience rising anxiety and bodily tension. After a seemingly interminable wait before the interview, my interviewers asked six questions, one of which I had not prepared for:

“Can you give us an example of when you have been in a position of leadership?”

I answered the five anticipated questions considerably better than this anomaly. I ensured that I spoke at a steady pace and referred to the criteria of the job description. My interviewers recognised this and commented on my feedback form that I did not rush or use filler words. However, I was so apprehensive that I failed to recall the STAR technique coherently. Fortunately, due to my extensive written and oral practice, I seemingly ingrained the STAR technique into my answer style subconsciously since my interviewers praised me for using this method in my feedback form. Nonetheless, they did propose that I could have been more concise, suggesting that my nerves triggered rambling and unnecessarily lengthy responses.

I forgot all my preparation for the unexpected question. In shock, I made up a situation that never happened! I tried to keep my composure, but my panicking mind meant I could not think straight.

Feelings:

Before the interview, the butterflies in my stomach rapidly grew, increasing my nerves and apprehension. Unhelpful anxious thoughts raced around my head, including: “What if I stutter and forget things?”

During the interview, these feelings of anxiety slightly eased since I was subconsciously distracting myself with the interview questions. However, some remaining mental tension made me feel unsettled and edgy. I thought I was rambling and answering the questions poorly without a concise structure.

I felt a surge of anxiety and guilt at the unrehearsed question because I invented an untrue answer. Despite trying to make my answer coherent, I kept having disastrous thoughts like “How could you cope with this in a real interview with real consequences?”

Evaluation:

Despite intense anxiety, my extensive preparation meant that I had subconsciously embedded the STAR technique into my mind and could structure coherent answers naturally. The feedback form from my interviewers praised my communication skills, enthusiasm, and ability to talk confidently without rushing. I gave detailed answers that referred to specific skills from the job description. However, since I became so distressed and overwrought before the interview, I could not focus and think clearly. Consequently, I hastily jumped into a difficult question with an untruthful answer that could have been truthful and more concise. Moreover, my interviewers noted that I should avoid fiddling with my chair. My intense mental unease would have caused this signal of anxiety.

Analysis:

Extensive written and oral preparation meant I could habitually articulate detailed answers with the STAR structure. My mental anxiety and scattered thoughts were likely due to the tense apprehension I felt preceding the interview. Such anxiety may be categorised as “communication anxiety [which] reflects feelings of nervousness or apprehension about one’s verbal communication skills” (McCarthy and Goffin 2004: 611-612). However, research highlights that even if candidates “anticipate questions they may get asked (…), they typically do not prepare and practice each utterance” (Brosy, Bangerter and Mayor 2016: 373). On reflection, I only told family members to ask questions I had prepared rather than formulating other unexpected questions that I had not considered. Rehearsing unfamiliar practice questions would have resulted in less panic, fidgeting and verbosity.

Conclusion:

Job candidates often experience “feelings of anxiety, frustration, and distress” during employment interviews (McCarthy and Goffin 2004: 607). Thus, I should have practised calming techniques (e.g., mindful breathing) that I could have implemented before the interview to avoid spiralling panicked thoughts. Furthermore, it is important to practice answering unfamiliar questions before an interview to become comfortable in coping with unexpected shocks. However, if you encounter an unforeseen question, you must think carefully about your response without launching into a rambling spiel of verbose nonsense.

Action Plan:

In future job interviews, I will ensure that I am more secure in my abilities and avoid spiralling into an anxious frenzy by implementing pre-interview calming techniques. In preparation for the interview, I will record myself answering practice questions (familiar and unfamiliar) to monitor my nervous fidgeting and assess whether my responses are articulated effectively with honesty, clarity and succinctness. These solutions will significantly improve my confidence and mental clarity when communicating my skills, qualities, and relevant experience to future employers.

New realities

Evidence suggests that “[job] interview anxiety is negatively related to interview performance” (Schneider, Powell and Bonaccio 2019: 328). Yet, new graduates are faced with the reality that “successful interviews are pivotal in transitioning from education to employment” (Lord, Lorimer and Babraj 2019: 1). Since my time at university will soon come to an end, job interviews are imminently approaching. Therefore, by refining and reflecting upon my interview technique and preparatory approaches, I aim to grow in confidence, clarity, and efficiency.

Bibliography

Brosy, J., A. Bangerter, and E. Mayor. 2016. Disfluent Responses to Job Interview Questions and What They Entail. Discourse Processes, 53.5-6: 371-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2016.1150769.

Gibbs, G. 1988. Learning by Doing. A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. London: Further Education Unit at Oxford Polytechnic.

Husebø, S. E., and S. O’Regan. 2015. Reflective Practice and Its Role in Simulation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 11.8: 368-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2015.04.005.

Juchniewicz, J. 2016. An Examination of Music Teacher Job Interview Questions. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 26.1: 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083715613590.

Lord, R., R. Lorimer, J. Babraj, and A. Richardson. 2019. The role of mock job interviews in enhancing sport students’ employability skills: An example from the UK. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 25: 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.04.001.

Markkanen, P., Välimäki, M., Anttila, M., and Kuuskorpi M. 2020. A reflective cycle: Understanding challenging situations in a school setting. Educational Research, 62.1: 46-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1711790 (accessed 23 October 2022).

McCarthy, J., and R. Goffin. 2004. Measuring Job Interview Anxiety: Beyond weak knees and sweaty palms. Personnel Psychology, 57.3: 607-637. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.00002.x.

Schneider, L., D. M. Powell, S. Bonaccio. 2019. Does interview anxiety predict job performance and does it influence the predictive validity of interviews? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 27.4: 328-336. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12263.

Walker, G. 1993. Mock job interviews and the teaching of oral skills. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 17.1: 73-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098269308709209.

Be Prepared!!

You May Also Like

To Be Or Not To Be – That Is The Interview Question

23 February 2023

BE A S.T.A.R 🌟

14 February 2023