Run(ner) of the Mill

When applying for a post-production placement with Lamb Films, I imagined myself sitting alone in a dark room hacking away at footage for hours. However, it was through spending a day on a professional set for the first time that I learnt the most about post-production’s range. I will use Gibb’s Model (1988, p.49) to organise my reflection. Its clear structure lends itself to the chaos of my day on set and it will allow me to consider the day’s events, as well as my constantly changing feelings. The consideration of these against each other will encourage me to be explicit in my learning and action for the future.

Description:

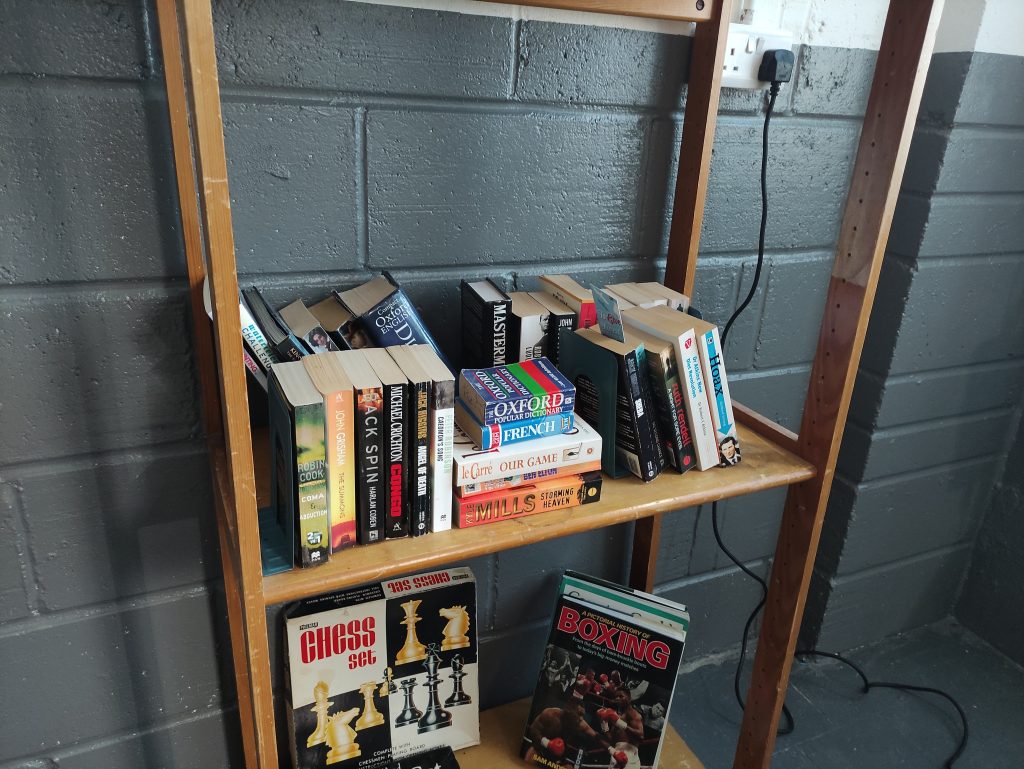

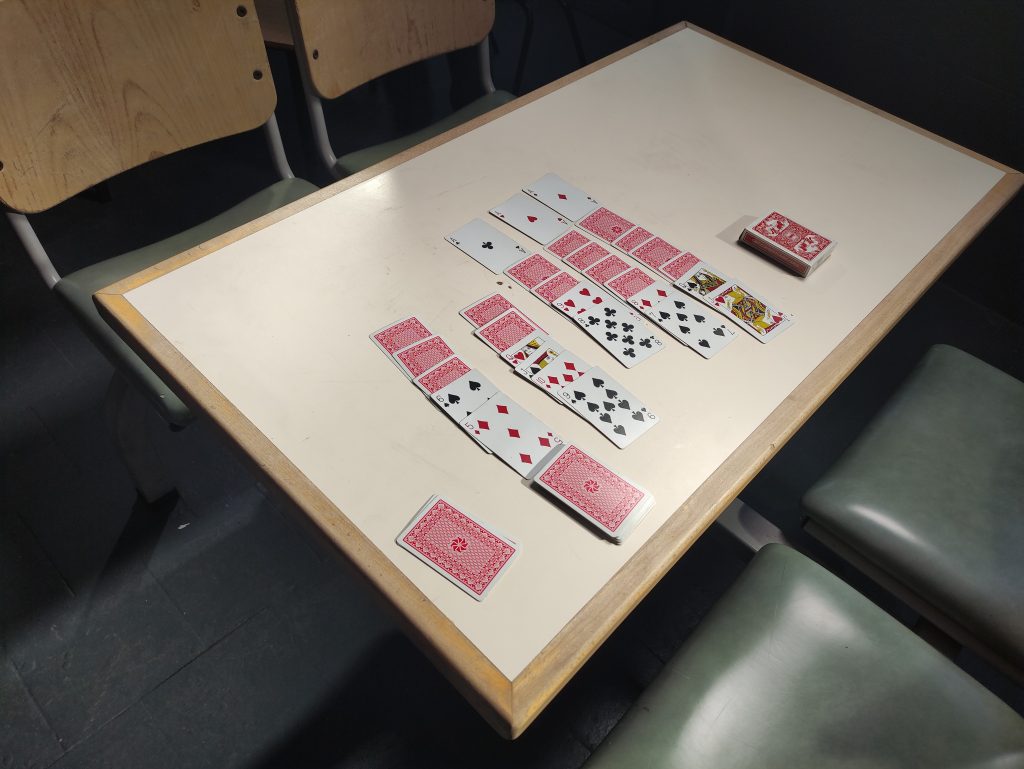

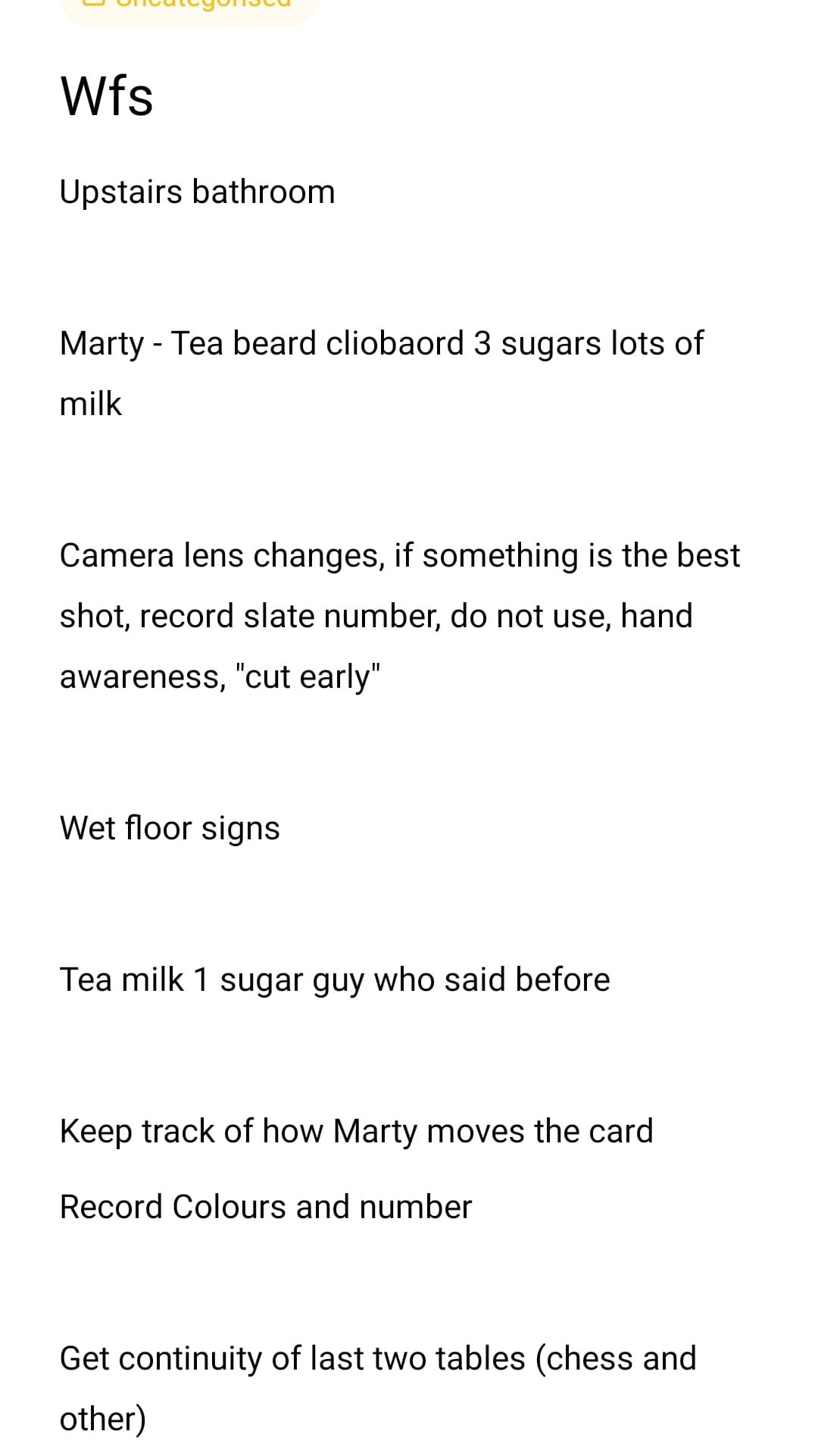

The set was a room in an old linen mill. The call time was 7am and shooting was to wrap at 5:30pm. Myself and another post-production placement student; Tori, were to alternate between a script supervisor role, and a runner role, as well as data wrangling when the camera’s cards were full. After borderline forcing the cast and crew to have a tea or coffee, I took to script supervising. Working closely with Alex; the production designer, I kept tabs on the set and the actors, taking photos to maintain continuity. After lunch I became a runner, perched down the hallway asking people to move through the busy mill quietly, and doing whatever else was required when we weren’t shooting. At 6pm, the actors and most of the crew headed home. The remainders of us finished at 7pm after hauling equipment through the mill.

Feelings:

I was picked up in the morning as anxious as if I were being conscripted to war. I had consoled myself by telling myself that as the day went on, I would go from being stressed to being bored. However, I found myself actually enjoying it. With my trusty notes page in my phone scattered with obscure tea and coffee orders, I felt more or less in control. We were coming up on 12 hours on set and it was just the dregs of us remaining. Being able to debrief with some of the crew members while taking equipment through the mill meant that I left feeling fulfilled and confident.

Evaluation:

I hadn’t printed off continuity sheets for my script supervising role. Hand-drawing sheets wasted time and made the information less clearly presented. This was at the start of the day where I could have been welcoming actors and extras and introducing myself. This also made me look unprofessional throughout the day, as I was carrying around a messy hand-drawn document.

Throughout the day, I became more engrossed in tasks that demanded my full attention, such as continuity. This appeals to me more than jumping from one task to another, as I did as a runner. Though I made an effort at the start of the day to ensure everyone was taken care of, by the afternoon, I was distracted by script supervising. It was to be a long day, as we were squeezing two days’ worth of filming into just one day, and people were getting tired quickly.

My focus on continuity did, however, mean that I performed my script supervisor role well. I felt comfortable doing this without getting distracted by other things on set. Script supervising also had more relevance to editing than my other tasks. I understand the practical necessity of ensuring that continuity is maintained between takes as I have been on the other end of dealing with problematic footage. It helped to know what to look out for.

Analysis:

My main issue was that practical, on-set work wasn’t what I had expected from my placement, and not what I have experience in. Resultingly, I had imposter syndrome (Mullangi, p. 403) where I felt pressure to do well. Being the least experienced on set meant that I neglected things that I know would have helped me to remain organised in favour of doing things how others were, such as memorising information rather than writing it down. I should have had the confidence to organise myself how I knew was best for me. As Eskritt (2014, p.240) concluded, some peoples’ memory improves from note-taking, while it diminishes others’.

Worrying leading up to the shooting day led me to underprepare, as I was avoiding addressing the day. This meant that I didn’t plan for my roles. This was particularly a problem when I was working with Alex, as the efficiency with which I carried out my role had a direct impact on how efficiently she was able to carry out hers.

Conclusion:

If I had this experience again, I would do more research on the roles I was to undertake. Doing this would have made me aware that I needed continuity sheets, and I would have emailed Larry (the producer) to organise this. I would use a more organised method of tracking the tasks that I had to do as a runner, for example, using a spreadsheet for tea and coffee orders. I could organise my notes in several ways, such as by importance, chronologically or by immediacy. Any of these, combined with what role a task relates to, would be the most useful method, as I was switching roles so frequently.

Action plan:

To follow through with this, I need to build my confidence by starting preparations well in advance of shooting. This will mean I’ll be able to create enough distance between myself and shooting that I will be able to engage fully with my preparations without it being clouded by worry. As I gain more experience in post-production, and particularly the on-set role of an editor, I am becoming more aware of how keen everyone is to help each other out, regardless of experience. Being engaged on set will be beneficial for me in getting future work. This was evidenced as members of the crew expressed interest in working with me again.

Bibliography

Eskritt, M. and Ma, S. (2013). Intentional forgetting: Note-taking as a naturalistic example. Memory & Cognition, 42(2), pp.237–246. doi:10.3758/s13421-013-0362-1.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by Doing, a Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. [online] Oxford Brookes University. Oxford Brookes University. Available at: https://thoughtsmostlyaboutlearning.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/learning-by-doing-graham-gibbs.pdf.

Mullangi, S. and Jagsi, R. (2019). Imposter Syndrome. JAMA, 322(5), p.403. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.9788.

You May Also Like

Interview a New You! – Becoming an Interview Guru

24 February 2023

The World of Theatre upon Reflection

30 November 2022