In at the Deep End: Recording an Orchestra

My first hours on work placement were some of the most densely packed learning experiences I have had in music production so far. I assisted a recording of the Ulster Orchestra in the Ulster Hall with Start Together studios. The whole session was videoed with a full camera crew for use on their social media platforms.

This session gave me an insight into orchestral recording that is exceedingly difficult to get. There were two key areas of development I took from this experience. Below I have used the Gibbs Reflective Cycle [1] to review what I learned:

- The Scale of Orchestral Recording

An orchestral recording is an enormous undertaking, especially in a venue as large as the Ulster Hall. We recorded 60 players, using 32 microphones. There were 3 audio crew (myself assisting, the producer and a recording engineer), 6 video crew, the venue technician and 2 Orchestra crew. For one, 7 minute recording, the session lasted two days – load-in, stage set-up, technical adjustments (during rehearsal), the recording itself and full tear-down. This practice of recording short pieces was new to me, although I had read an interesting summary beforehand of the differences between pop and classical recording industries by Donald Passman. [2]

Initially this seemed daunting, especially given my inexperience working with an orchestra. It certainly proved to be physically tiring, especially given the 8:30 AM start on the day of recording. As with so much in music, however, the scale and difficulty of the project made it all the more rewarding – the moment of bated breath after the final take was captured was sufficient payoff! I also felt enormously privileged to be able to work in the Ulster Hall, such a significant venue in Northern Ireland. And, of course, the orchestra are so impressive in their professionalism and skill that I felt very lucky to have been able to be a part of the production.

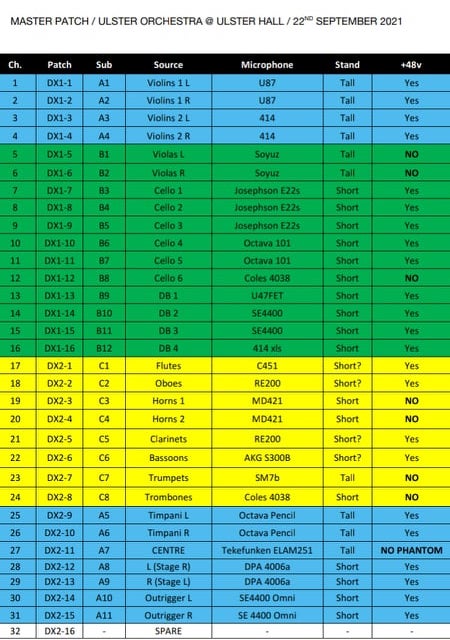

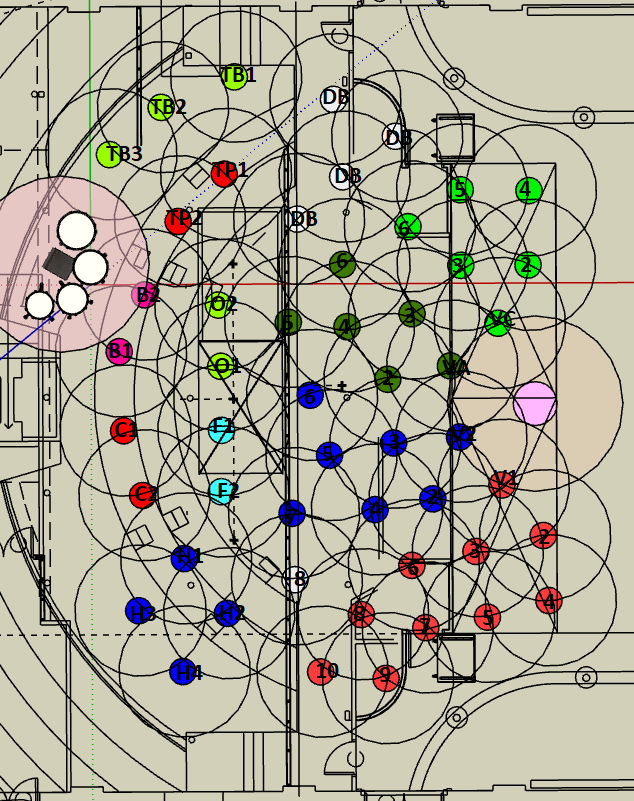

What I learned from the scale of this session was the importance of pre-production. In previous recording experiences, both shadowing and in my own work, pre-production has always served to maximise productivity, or a good way to expedite technical decision-making mid-session. In this session, however, it was absolutely essential – the work would not have been possible without incredibly detailed planning. I have included the channel-list and stage plot for reference.

These two documents allowed for smooth delegation of roles within the audio crew. I confidently place microphones on-stage using these documents while the producer and engineer organised the overall recording infrastructure and set-up communications for the whole team. Then the producer could come across the stage and refine the mic positioning, with them already being cabled and roughly placed, saving significant time. The channel list also meant microphones could be added or changed with confidence that it would not disturb what was already in use. An example of this is how we discovered, once the orchestra’s were set, that there was a position laid out for a tuba that was not accounted for. This was easily rectified as we has a spare mic in the inventory, and we could quickly find the spare input channel and where it was located on stage to have a mic placed by the time the players took their seats. This also gave me a chance to see, in action, the necessary technical knowledge Michael Zager describes in his book Music Production. [3]

This approach to thorough session preparation will stay with me. I will keep full channel lists and stage/studio plots for all of my own recording projects in the future. This will help me maximise my productive time and allow the artists the space to be creative without being encroached on by technical time-wasting. I am very appreciative to Niall (producer) for sharing all of his pre-production with me in advance, this gave me a template off which to base my own prep in the future.

- Etiquette when working with the Orchestra

The second lesson I took from this session, which was surprising to me, was the etiquette around working with an Orchestra. There is a marked difference from working with rock and pop artists in a recording studio environment. The orchestra are very particular about their set-up and their space: their own technicians lay out seats and instruments to a specification and once they are in place they are not to be moved. This is for a combination of sound, comfort of the musicians, and a strict 2m social distancing rule. This presented a steep learning curve for me. In my previous experience it has always been acceptable to ask musicians to manoeuvre themselves or adjust their playing in order to maximise the sonic quality of the recording… not in this case. At one stage we were having a problem with mic bleed from the timpani into the bassoon mic so I suggested to Niall that we move the Bassoon position slightly to improve this. Niall explained to me that it is a big ‘no-no’ to ask any orchestral musician to alter their position for the sake of the recording.

At one point, without realising, I moved the stool of one of the double bass positions in order to lay an XLR cable. Immediately Niall noticed and explained that I had to go back to the stage plot and measure to get it back to the exact position laid out by the orchestra technicians. Learning from this for the future I will pay careful attention to the way in which performing one task may disturb the work done beforehand.

In this type of recording communication is key. The three teams orchestral, audio, and visual all had to contribute to the same recording but with consideration to the needs of the others; and always in the way that gave the orchestra the purest experience of music-making and preserved the quality of the final project. To fit into this structure I had to make sure that every task I did, even as small as tidying up a cable run on stage, was approved by the relevant team so as to not disturb the other facets of the production. After this session I found an interesting article on the factors that contribute to successful teamwork in the creative industries, which articulates the teamwork I observed at placement. [4]

[1] Gibbs, Graham. Learning By Doing: A Guide To Teaching And Learning Methods. Oxford Further Education Unit, 1988.

[2] Passman, Donald S. All You Need To Know About The Music Business. 10th ed., Simon & Schuster, Incorporated, 2019, p. 423.

[3] Zager, Michael. Music Production: For Producers, Composers, Arrangers And Students. 2nd ed., The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2011, p. 171.

[4] Černevičiūtė, Jūratė, and Rolandas Strazdas. “Teamwork Management In Creative Industries: Factors Influencing Productivity”. Entrepreneurship And Sustainability Issues, vol 6, no. 2, 2018, p. 512. Entrepreneurship And Sustainability Center, https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2018.6.2(3). Accessed 5 Nov 2021.

You May Also Like

AAAH or (Why Tom sucks at selling himself)

25 November 2021

Breaking into the Film Industry: What You Know or Who You Know?

24 November 2021