Trisha Forbes and John Moriarty describe their collaborative project with AWARE-NI and Queen’s and Ulster Universities to develop an online training platform aimed at improving workplace wellbeing via improved ‘Mental Health literacy’

AWARE is the depression charity for Northern Ireland, with a stated mission of achieving “A future where people can talk about their mental health openly, access services appropriate to their needs and have the skills and knowledge to maintain positive mental health.” Through the delivery of its Mood Matters programme in diverse workplaces across Northern Ireland, AWARE has recognised the importance of the world of work to one day declaring that mission accomplished.

iAmAWARE is an online stress reduction programme which introduces participants to signs and symptoms of depression and anxiety and offers suggestions for potential coping strategies and stress reduction techniques based on the principals of self-help strategies and cognitive behavioural therapy. Our team of organisational and mental health researchers from across Queen’s University Belfast and Ulster University were privileged when AWARE approached us with their vision for iAmAWARE and a proposal to partner and use our research skills to complement their existing wealth of expertise.

Why target workplaces?

People’s jobs are often where they access key information, like which fire extinguisher to use for electrical equipment versus a kitchen fire, or their statutory entitlements to different types of leave and welfare support. Some of that occurs through formal organisational policy and provision, though the togetherness of work also generates informal information networks. So a poster in the tea room can be doubly effective in directing someone to information about mental health, while also starting a conversation among colleagues.

(This civic role of employers has been underscored during the pandemic, where government has effectively relied on employers to administer welfare as well as administer public health advice and enforce guidelines.)

Additionally, work itself can be a key part of the story of why someone experiences good or poor mental health. Work can be a source of identity, pride, friendship and purpose. It can also be stressful and energy sapping if the work conditions are poor and support is low. Furthermore, stressors from across different areas of life can come to a head in the workplace. Someone who successfully puts on a brave face for family members or tries to act the happy warrior for friends could be pushed to their limit by a work scenario. Therefore the idea of mental health literacy is to help people recognise signs of strain both in themselves and in others.

From in the room to on the screen

Mood Matters was AWARE’s original face-to-face intervention delivered through interactive group sessions, usually within or near people’s place of work. Even prior to the pandemic, there were always hard-to-reach employers and employee groups, such as those working outside normal office hours, or travelling a lot as part of a work routine, pointing to a need for iAmAWARE. Through a grant from the Wellcome Trust, we have been able to engage design experts to adapt that material to an online platform incorporating infographics, video, reading, opportunities for reflection and signposting to support.

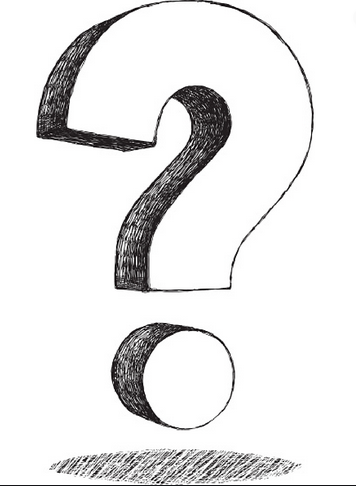

The real-life examples AWARE provide are drawn from years of experience of talking to workers about the challenges they face. In a short video clip, Training Officer Marina McCully introduces participants to a scheme for recognising ways to break down a common workplace sensation of being overwhelmed, by taking a step back and observing our thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and behaviours.

This can then lead us to see how these different experiences interact and form our coping response to stressful events, sometimes creating a vicious cycle where one negative area spills into the next and so on. Recognising this pattern in ourselves or our colleagues can be crucial to moving towards a more ‘virtuous circle’.

The role of the researchers has been to amplify the voices of the people who will be the end users of the programme. This has involved in-depth conversations with volunteers from two organisations, PwC and the McAvoy Group. We held focus group discussions with three groups of employees (“frontline” or client facing staff, human resources and senior management) to understand participants’ views on mental health generally, as well as challenges faced by participants regarding their mental well-being in the workplace. This gave us a breadth of perspectives on what is already being done by employers to address these challenges, and what might be done in the future.

Participants were then given access to the iAmAWARE online platform for verbal feedback, which has significantly guided subsequent re-design and refinement. At present, a wider group of employees are being given the chance to take the latest version of the training and in-built surveys are capturing further feedback as well as information about those employees’ well-being at work, knowledge of, and attitudes towards, mental health and ill-health.

The pandemic has presented a challenge for the research and for the interpretation of the data and one which we continue to confront. However, it has also been an event which has underscored and strengthened the need for high-quality accessible training which (a) is not dependent on being at a certain place and time and (b) enables workers to reflect on the implications for their wellbeing of curtailed schedules, work from home and work-life balance in this changed work landscape. We have been able to capture some of these early reflections through our survey and it is clear the delivery of the programme will have to evolve and be adaptable to a range of possible scenarios over the coming years.

Research Team

Queen’s University Belfast: Dr Trisha Forbes, Dr John Moriarty, Dr Karen Galway, Dr Paul Best and Dr Heike Schroder

Ulster University: Dr Paula McFadden, Dr Patricia Gillen and Prof Mark Tully

The design work on iAmAWARE programme is thanks to Creative Three Media (@wecreativ3). 2020 has been an unbelievably tough year for small businesses, so please support yours!