Black History Month 2020 : Black History online : Irish historical newspapers

Online historical archives present challenges as well as opportunities for the researcher. On the one hand, what is there not to like about having content spanning hundreds of years from numerous publications at the click of a mouse? On the other, searching through such vast quantities of material can be a daunting experience. How do you find what you are looking for? How do you be sure not to miss anything? How can you do all of this without feeling overwhelmed?

To mark Black History Month 2020 we are going to consider how to get best use out of online archives. In the first of two blog posts we shall first consider historical newspapers, with a particular focus on Irish Newspaper Archives.

Irish Newspaper Archives is a multi-title platform offering subscription access to Irish newspaper content from 1738 to the present day. The database can be searched across all titles, or particular titles and searches may be limited by date. Full text is viewable in search results and is further enhanced by the ability to view retrieved results within the context of the whole publication.1. Irish Newspaper Archives is available to Queen’s staff and students via the Library Catalogue.2.

Finding material on black lives in Ireland is challenging. We know that small numbers of Africans did live in Ireland from the eighteenth century. Casual references to ‘blacks’ and ‘negroes’ for example, in contemporary Irish newspapers testify to the fact that black people did exist in Ireland at this time. 3 However black lives are not immediately evident in these sources, and when we find them they refer mainly to places outside Ireland. Furthermore, we need to keep in mind the type of resource we are using. Newspapers reflect prejudices, practices and expectations of their publishers and their readership. So while we are looking for black lives we will need to step through opinions and interests of this readership to get to any historical facts.

When searching newspaper archives it is easier to locate references to particular individuals or specific groups of people. What do you know about black lives in Ireland? Searching for key names will often yield results. Our first approach to finding references to black lives in this type of resources is therefore to search for specific people. The most famous black visitor to Ireland in the nineteenth century was Frederick Douglass, and his mid-nineteenth century tour of Ireland was well documented at the time, revealing much about Douglass, the reception he received, anti-slavery movement in Ireland and the opposing support for the southern states in America in Belfast.

When Douglass visited Ireland in 1845 and 1846 his touring lecture series stopped in Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick before he reached Belfast in December 1845. Douglass reportedly had misgivings about visiting Belfast, regarding it as a “hotbed of Presbyterianism and Free Churchism”. Indeed, his reception was mixed: Douglass had been travelling around Ireland for four months and had presented over fifty lectures on slavery and temperance but “it was not until reached Belfast that I had even been asked for credentials” 4

Douglass gave multiple lectures on American slavery at the Presbyterian Church in Donegall Street in December 1845.5 Local newspaper coverage at the time gives us some insight into the the reception given to an escaped slave and active abolitionist in 1840s Belfast by those whose interests aligned with slave owners in the American South. He recounted the accusations that he was an imposter as one example of of the obstacles he encountered on his first visit when he returned to Belfast in June 1846:

“ I came to this town, six months ago, under considerable embarrassment. I brought with me documentary evidence of my being what I represent myself to – an American slave. I was met upon the threshold, by insinuations from high places, that I was not the person I represented myself to be, and you may recollect our first meeting – you recollect the under-current of influence which was directed against me—the whisperings in corners, which were prevalent. You recollect what cautions were given – “Beware of this Douglass doubtful character.” (Hear, and laughter.) I feel a degree of pleasure, therefore, in appearing here this evening, after having stood the ordeal of a five months conflict with men as sagacious and as powerful as any in the three kingdoms, and after having come out of it unscathed. (Cheers.) Since I last addressed an audience in Belfast, all Britain has become convinced that whatever else may be false with me, I am truly an American slave.”

Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938, Friday, June 19, 1846; Page: 1

Douglass’s lecture tour was reported in some detail in the Irish press at the time. Sometimes controversial depending on the audience, his events were always well attended. This snapshot of a famous anti-slavery campaigner touring Ireland takes in the associated transatlantic connections between that movement in Ireland and in Boston and Philadelphia, further details of who was involved in that movement and activities undertaken, An address from the Committee of the Belfast Ladies Anti-Slavery Association in 1845, which includes a list of members and some detail on money raised, called on the “pious women of Ulster, who delight in promoting missions, [ how can they] remain inactive whilst the adopted home of so many of their countrymen presents such a revolting anomaly as slavery in a country calling itself Christian?” 6

The impact Douglass had on Ireland continues and this public history of black lives in Ireland is also recorded in the archives. To mark the place where he had spoken in Waterford, a blue plaque was unveiled at Waterford City Hall in 2013. 7 In 2008 Irish broadcaster TG4 aired a documentary Frederick Douglass agus na Negroes Bána (Frederick Douglass and the White Negro) about the escaped American slave who found freedom during the Irish famine. 8

Our second approach to searching online historical archives is structured browsing using a broad keyword along with dates. When browsing by keyword for material on black lives, think about how these were likely to have been reported. How and where were black people living in Britain and Ireland at this time? Service was a common employment, although specifically Irish results are not easy to come by. These results therefore reveal more about attitudes towards black servants reported in Ireland than actual black lives in Ireland. Having a black servant was evidently a fashionable accessory in some quarters. Search for “black servant” and a report from 1764 notes how the black servant of the Prince of Lichtenstein was regally attired in “sky-blue edged with silver”.9. Kudos for the moral mission of employers is also evident in a 1765 report that a “negro black servant was baptised in the Parish of St Nicholas. without”.10

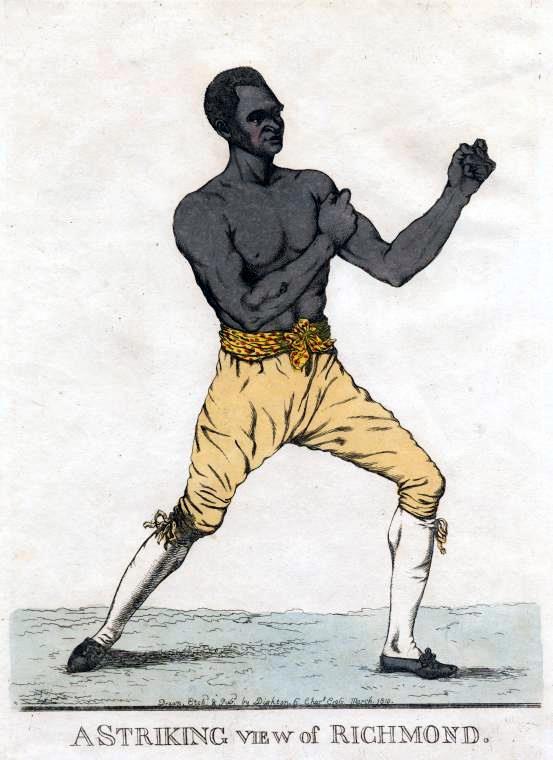

Searching for servants can also reveal other details. The same search reports a boxing match between “George the black servant of Captain Smith and Sam Arnold a noted wrestler and boxer from Gloustershire” in London, 1819. The match, initially halted by two constables until they were “blue ruined until they forgot their errand” lasted six rounds and a full match report was provided before Arnold “although a winner, could not walk”11 . The reporting of this event is a useful indication of how the sport of boxing was regarded as a legitimate platform for black lives at this time. Context to this must come from the most famous black boxer at this time, Bill Richmond, a former slave who arrived in England from the American colonies following the war with General Hugh Percey, 2nd Duke of Northumberland.12

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Richmond#/media/File:Bill_Richmond_1810.jpg

Other keywords reflect usage at the time: a search for “negro” reveals reports on a “negro duel” in Louisiana 13 and and “a negro marriage” custom in Angola. 14 These reports reached Ireland via news sources in England, the United States and Canada. Alongside the racial stereotypes and prejudice at their heart, such reports give some insight into the fascination with difference in Irish news and the nineteenth-century news trail between America, England and Ireland from which much of it derived.

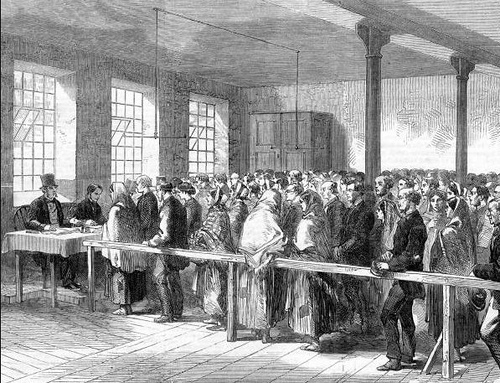

Exploring black lives can also usefully include events directly impacting upon black lives across the ocean and the impact these events had in Ireland. The American Civil War (1861-65) was well reported in Ireland. A keyword search for “civil war” and American for the years 1861-1865 reveals public lectures on the event advertised at the time reflecting some general interest in events, as well as particular concern about the impact of the Union blockade on cotton exports from the southern states. This blockade of cotton exports impacted on English towns such as Lancaster and “subscriptions received for the relief of the distressed cotton operatives of England” are listed in The Belfast Newsletter in 1862 15

The blockade also threatened to directly effect cotton imports in Ireland, most notably in Belfast which imported two-thirds of cotton supplies directly from America.16 In January 1861, the Belfast Newsletter reported it’s sense of alarm about the impact of cotton shortages in Belfast muslin trade chiefly among chiefly female employees “scattered throughout Ulster”.17

That a perilous crisis is impending over the greatest manufacture of the British Islands few will have the hardihood to deny. At present, before a single life has been lost, or a single skirmish has occurred, the secession of the Southern States has created excitement in the market for the staple production of America, and among those who are most interested in the greatest trade of England … The anticipated deficiency of the raw material must have an effect, greater or less, upon the two great sources of industry which this country still possesses. Belfast is the centre of the sewed muslin trade, which employs about 300,000 persons, chiefly females, scattered through all the counties of Ulster. The employment is wholesome, cheerful, and remunerative one, and a diminution of it would materially decrease the comforts of a large number of families. If cotton be scarce, muslin must become dear—not merely in proportion to the greater price of the raw material. When the embroidered articles become dear, according to a universal law there is less employment. We are deeply interested, then in this cotton-producing question.

Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938,Saturday, January 26, 1861, p. 2

The American Civil War was therefore closely followed in Ireland, and especially in Belfast where reports on cotton supplies continued throughout the conflict.

- https://www.irishnewsarchive.com/about-us

- Irish Newspaper Archive: https://encore.qub.ac.uk/iii/encore/record/C__Re1000058

- Hart, W. A. “Africans in Eighteenth-Century Ireland.” Irish Historical Studies 33, no. 129 (2002): 19-32. Accessed October 26, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30006953.

- The Liberator, March 20 1846 quoted in Maclear, J. F. “Thomas Smyth, Frederick Douglass, and the Belfast Antislavery Campaign.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 80, no. 4 (1979): 286-97. Accessed October 19, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27567581.

- Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938, Friday, December 26, 1845; p. 3

- Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938, Tuesday, September 29, 1846. p. 4

- American slavery abolitionist Frederick Douglass honoured. Munster Express, October 11, 2013, p.20

- TG4 tells story of slave who found freedom in famine. Connacht Tribune, March 28, 2008, p. 23

- Freemans Journal 1763-1924, Saturday, March 03, 1764, p. 2

- Freemans Journal 1763-1924, Thursday, May 21, 1772. p. 2

- Boxing. Freemans Journal, Tuesday, October 26, 1819; p.4

- Obi, T.J. Desch. “Black Terror: Bill Richmond’s Revolutionary Boxing.” Journal of Sport History 36, no. 1 (2009): 99-114. Accessed October 26, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26405256 ; David Olusoga presenter and writer, “Black and British: a forgotten history”, BBC. Accessed 25/10/2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episodes/b082x0h6/black-and-british-a-forgotten-history

- A negro duel. Waterford News, Friday, August 24, 1849, p.4

- A negro marriage. Saturday, December 20, 1845, p.4

- Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938, Friday, June 19, 1846; p. 1

- Bielenberg, Andy, and Peter M. Solar. “The Irish Cotton Industry from the Industrial Revolution to Partition.” Irish Economic and Social History 34 (2007): 1-28. Accessed October 26, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24338852.

- Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938,Saturday, January 26, 1861. p.2