By Hue Dang

When I first started learning about machine learning and deep learning, I often followed project tutorials, coding along with the steps the author had outlined, using the same inputs and algorithms. However, sometimes my model would perform worse than the tutorial author’s model. Maybe you’ve been in a similar situation, too. Another scenario where we might care about the perfect reproducibility is when we want to share an experiment with our colleagues, ensuring they can achieve the same results. Yet, they may not reproduce the high performance you did. So, what causes these differences? In this post, we will explore the factors affecting the reproducibility of machine learning and deep learning models in such situations and discuss what we can do to address them.

Numerical Errors: A Challenge to Reproducibility

You may wonder, what exactly does reproducibility mean in deep learning? Reproducibility in machine learning means being able to repeatedly run your algorithm on specific datasets and obtain the same or similar results for a given project.

Recently, applications of deep neural networks (DNNs) have grown rapidly, as they are able to solve computationally hard problems. A recent report by McKinsey estimates that AI-based applications have the potential market values ranging from $3.5 and $5.8 trillion annually[1]. These technologies are increasingly used in safety-critical applications such as medical imaging [2] and self-driving cars [3], where user safety and information security are paramount. Unlike traditional software systems, which are programmed based on deterministic rules (e.g., if/else), the deep learning (DL) models within AI-based systems are constructed in a stochastic way due to the underlying DL algorithms, whose behaviour may not be reproducible and trustworthy [4].

Though significant research effort has been made in verifying the behaviour of machine learning systems and developing tailored training techniques, most of these methods developed so far do not account for slight behavioural differences arising from different numerical implementations. Unfortunately, these small differences after propagating hundreds of neurons and dozens of layers cause significant changes in system outputs and have been identified as causes of differences in the behaviour of neural networks. For instance, Sun et al. [5] showed that instabilities arising from floating-point arithmetic errors during training, even at the lowest precision, can significantly amplify, leading to variances in test accuracy comparable to those caused by stochastic gradient descent (SGD).

Sources of numerical errors

Let’s look into primary sources that cause numerical instabilities in deep learning and why it matters for the reproducibility in deep learning systems.

Different software implementations

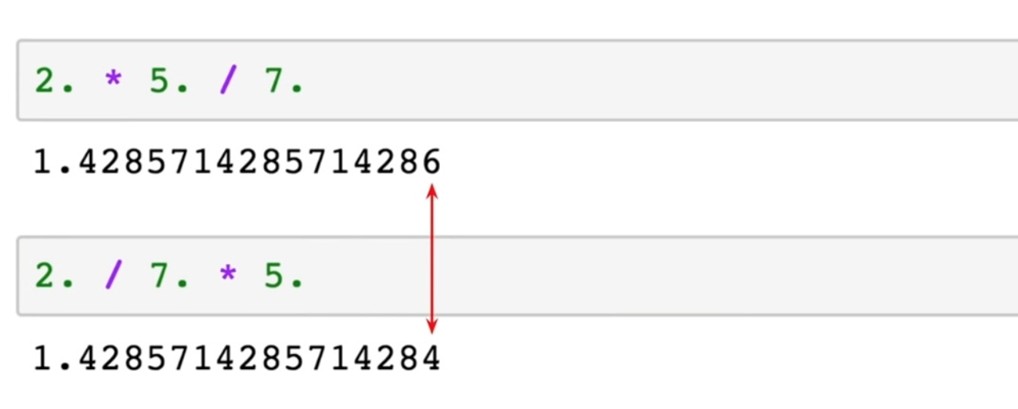

The first source that affects numerical accuracy and causes numerical differences between neural networks is the differences originating from different software implementations [6]. For example, operation orders are changed when implementing the algorithms. In some cases, we might think that the order doesn’t matter, because mathematically the result should be the same. But when we are using float with limited precision, we do not get the exact same results, as shown in the example below. During training, these tiny differences will accumulate and we may end up with significantly different outputs in the end.

Figure 1: Different operation orders lead to different results.

Different numerical precision

Using different representations for continuous numbers across different hardware and software platforms is a popular source that leads to variances in the performance of neural networks [7]. Often, neural networks are trained using servers with high computational capacities, but then deployed in personal devices without the same computational capabilities. The trick is often done by reducing the precision size, or pruning neural networks; however, in most cases the loss of precision comes without any guarantees on the resulting neural network’s behaviour.

Different hardware specifications

Deploying neural networks on hardware with different specifications (e.g., those with higher soft-error rates) may yield differences in the behaviour of deep learning systems [8].

Figure 2: A single bit-flip error leads to misclassification of image by the DNN [8]

Next steps

These situations motivate the development of new methods that ensure the reliability and robustness of deep learning systems against numerical errors in different scenarios. This is also the problem defined in my project. We aim to understand what happens in a deep learning system when the network is deployed in different hardware, has different software implementations, or encounters perturbations in inputs, weights and architectures.

Below are some future directions to address the problem of numerical errors in deep learning systems:

- Developing new methods, algorithms and related software implementations for analysing the numerical accuracy and reproducibility of deep learning training and inference tools across different software and hardware platforms.

- Developing new methods for training models to be more robust and provably robust against possible numerical errors.

- Proposing techniques to detect and avoid errors, and mitigate the instabilities caused by errors.

Conclusion

In this blog, we examined the issue of reproducibility in deep learning, which is affected by numerical accuracy problems. By addressing the sources of numerical errors, we can develop more reliable and robust deep learning models, thereby improving their trustworthiness and effectiveness across various applications.

Stay tuned for the next blog post, where we will explore some of the methods that have been developed to tackle this issue. See you next time!