Changing voting behaviour in Northern Ireland: A ‘third way’?

In most of the UK, voting behaviour is determined by things like class, education, and economic issues. In Northern Ireland, these variables are not absent, but they do not dominate in shaping voting behaviour. As a deeply divided society, politics has long been dominated by the contest between unionists and nationalists, tied up with religion and sectarian segregation (Tilley et al., 2019). However, the impact of consociational power-sharing, Brexit and changing attitudes to identity have complicated this picture (Murphy, 2023). This blog post will examine the rise of middle ground or ‘third way’ parties and will consider possible impacts on Northern Ireland’s political and constitutional future.

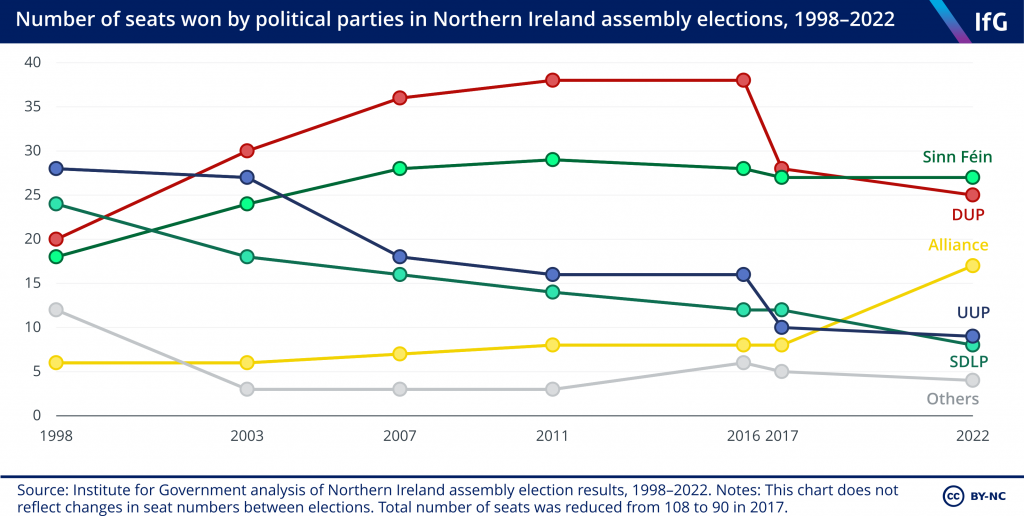

Figure 1: Northern Ireland election results 1998-2022, Institute for Government

Cleavages and matters of salience in electoral politics usually reflect divisions in society, often serving to reinforce those divisions (Tilley et al, 2019). As a result, in deeply divided societies, political parties often manipulate divisive societal divisions for political gain (Tilley et al, 2019). This has long been the case in Northern Ireland. During times of insecurity for the two communities, such as the Troubles or the first years of power-sharing, some unionist and nationalist parties adopt narrow ethno-national approaches to garnering support from their respective voting bases (Murphy, 2023). During the Troubles, voter behaviour was directed by the intensification of ethno-national division; elections became little more than ‘sectarian head-counts’ of each community (Murphy, 2023). With power-sharing under the 1998 Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, it was hoped that the institutions would facilitate cooperation, moderate party positions, and allow competition on other, non ethno-national issues (Tilley et al, 2021).

As figure 1 illustrates, the question of Northern Ireland’s constitutional future continues to be consequential in shaping voting behaviour (Murphy 2022). Yet, it also shows how the middle ground, largely represented by the Alliance Party, is gaining momentum. At the 2022 Assembly election, the pro-European Union (EU), neither nationalist nor unionist Alliance Party won the biggest gain in vote share, from 9.1% in 2017 to 13.5% in 2022 (O Dochartaigh, 2022; ARK, 2023). This was enough to make the party Northern Ireland’s third largest, ahead of the historically dominant Ulster Unionist Party (O Dochartaigh, 2022). Three events or changes can be interpreted as altering voting behaviour in Northern Ireland away from the dominance of orange and green politics, to a landscape where the middle or third way is growing. These are the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, Brexit and changing identity cleavages.

The 1998 peace agreement created the institutions of cross-community power-sharing that governs Northern Ireland today. It was hoped that, under a system that required cooperation across the traditional orange and green divide, the respective parties would be incentivised to moderate their positions and compete on left-right, ‘bread and butter’ economic issues (Tilley et al., 2019). According to Tilley et al, the main unionist and nationalist parties have moderated their positions, but ‘bread and butter’ politics have not replaced the constitutional question in terms of salience (2019). However, the often competing interests of the unionist and nationalist bloc has served to frustrate the work of devolution, leading some voters to search for a non-sectarian party with ‘bread and butter’ politics as a priority.

Brexit has shaken politics in Northern Ireland, with the middle ground Alliance Party benefitting from increased representation at Stormont. In the backdrop of most people rejecting Brexit in Northern Ireland, the pro-EU Alliance Party supported the softest possible version of withdrawal to avoid a hard border in Ireland (O Dochartaigh, 2022). This position attracted support from nationalists and liberal unionists, both of whom were opposed to Brexit, especially any form of withdrawal that would damage Northern Ireland’s relations with the Republic of Ireland and EU (O Dochartaigh, 2022). This is an example of voting behavious shaped by practical and economic concerns, rather than the ethno-nationalism of traditional orange and green politics.

Changing identity cleavages have also increased among voters the salience of the middle ground. As Murphy states, support for the middle ground Alliance Party is more than short-term disillusionment with the Democratic Unionist Party’s handling of Brexit, or the fact that Sinn Fein’s first priority is constitutional change (2023). Rather, over recent years, the identity of people in Northern Ireland has been changing, with discernible impacts on voting behaviour (Murphy, 2023). Although not a majority, an increasing number of people do not identify as either unionist or nationalist; many people also don’t subscribe to the Protestant or Catholic religious labels (Murphy, 2023). Instead, many people now consider themselves Northern Irish, do not claim to be just British or just Irish, and are not interested in tribal politics. This growing cohort of voters explains the continued increase in the middle ground’s electoral fortunes.

The type of issues that influence voting behaviour in the rest of the UK, while not irrelevant in Northern Ireland, have often been subjugated under the dominance of the orange and green agenda. Throughout Northern Ireland’s history as a deeply divided society, voting behaviour was marshalled into a tribal form of politics, a contest of strength between the unionist and nationalist communities. In recent decades this has changed. The Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, Brexit and liberalising changes in identity cleavages have enticed voters to change long-established behaviour and vote for non-sectarian parties. If this continues in the years to come, a review of the Assembly and Executive, which favour unionist and nationalist parties, will become both necessary and urgent.

Bibliography:

ARK. (2023). ‘Who won what when and where’, ARK Northern Ireland Elections. Available at: https://www.ark.ac.uk/elections/ (Accessed: 8 April 2024)

Murphy, M.C. (2023). ‘The rise of the middle ground in Northern Ireland: What does it mean?, in The Political Quarterly, 94 (1).

O Dochartaigh, N. (2022). ‘The rise and rise of a new majority in Northern Ireland’, in UK in a changing Europe. Available at: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/the-rise-and-rise-of-a-new-majority-in-northern-ireland/ (Accessed: 8 April 2024).

Sargeant, J. and Rycroft, L. (2022). ‘Northern Ireland assembly’, Institute for Government. Available at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/northern-ireland-assembly (Accessed: 8 April 2024).

Tilley, T. et al. (2019). ‘The evolution of party policy and cleavage voting under power-sharing in Northern Ireland’, in Government and Opposition, 56, pp. 226-244.

The introduction of this blog is very strong. It provides great context behind voting behaviour in Northern Ireland and affirms to the reader that in the Northern Irish context, voting behaviour is less impacted by traditional cleavages like class or economic issues, but instead is largely influenced by ethno-nationalism and sectarian segregation. The author also provides a succinct overview of why this is.

Moreover, the author conveys how the Alliance Party have rose to prominence in NI in recent years as much of the electorate has moved away from sectarian divides and has opted for a third option in the form of the Alliance Party who designate as ‘other’. The author successfully utilises graphs and statistics to highlight this and attempts to provide some explanations, citing Brexit and changing identity cleavages.

However, I think the analysis regarding the reasons for the growth of the Alliance Party could be developed. For example, the author claims that Brexit is one of the reasons for the Alliance Party’s newfound growth and contends that Alliance’s pro-EU stance has ‘attracted support from nationalists and liberal unionists, both of whom were opposed to Brexit’. Yet, the SDLP and UUP are moderate nationalist and unionist parties respectively who also supported remain and yet, they have not enjoyed this same growth in success and have instead experienced a steady decline over the last decade. In fact, the SDLP and UUP have largely suffered at the hands of the Alliance party as many of their voters have switched allegiance to Alliance. Although the author attributes this to Alliance’s ‘Remain’ position, since all three parties took a pro-EU stance, there must be further explanations for why Alliance has enjoyed the votes of more moderate nationalists/unionists since 2019, which the author should develop.

The SDLP and UUP are notably absent from this blog in its entirety, and it would be favourable if the author provided some commentary on why many moderate nationalists and unionists have turned away from these parties in favour of the Alliance party, and this would further strengthen the blog’s analysis on the growth on the Alliance Party.

Overall, this is a concise blog that shows a good-grasp of the main issues regarding voting cleavages in Northern Ireland.

This post offers a comprehensive analysis of the evolving voting behaviour in Northern Ireland, particularly focusing on the rise of middle ground or ‘third way’ parties like the Alliance Party. While the impact of consociational power-sharing, Brexit, and changing attitudes towards identity is well-addressed, something else to consider and add to the discussion may be the role of generational shifts in shaping voting patterns. Generational differences in attitudes towards identity and politics could be contributing to the growing support for middle ground parties. Younger voters, in particular, often exhibit more progressive and inclusive views on identity, preferring to transcend traditional sectarian divides and prioritise issues such as environmental sustainability, social justice, and economic equality. This generational shift is evident in recent surveys and polling data, which indicate that younger voters in Northern Ireland are more likely to identify as Northern Irish rather than exclusively unionist or nationalist. Moreover, the advent of social media and digital communication platforms has facilitated greater political engagement among younger demographics, providing them with alternative sources of information and avenues for activism beyond traditional party politics. Middle ground parties like the Alliance Party have effectively leveraged digital campaigning strategies to connect with younger voters and mobilise support around issues that resonate with this demographic, such as climate change and LGBTQ+ rights. By acknowledging the influence of generational dynamics on voting behaviour, we gain a deeper understanding of the shifting political landscape in Northern Ireland and the potential for further growth of middle ground parties.

Dear qub.ac.uk administrator, Thanks for the well written post!

nogensinde løbe ind i problemer med plagorisme eller krænkelse af ophavsretten? Mit websted har en masse unikt indhold, jeg har