Populism: will Britain succumb?

This blog will deliberate on how populism has begun to appear in British political discourse since the Brexit referendum, how it is manifesting, and reflect on the future of British politics, or as may be the case, British populism. While this blog will focus on Britain and the problems it is causing, the very ideology is rather infectious, and it is important to speak about this briefly. Naturally, populism is an ideology that pits ‘the people’ versus ‘the elite’, and is a thin centred ideology which is used almost as a specifier – it is attached to general political ideologies such as fascism, liberalism, socialism, etc (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017). It also focuses on the general will of the people, often through the lens that the elite are obstructionist to what the people want. However, populism is a threat merely because of illusion (Covington, 2018: 262). Many ‘populists’ are in fact well established, possibly even part of the elite. The illusion, therefore, is that they are ‘for the people’, when in reality, it is only that. An illusion. It is the face of loss that those inclined to support populists feel, and that this loss, e.g. poverty, can be remedied by being in and supporting these in-groups that populists construct (Covington, 2018). So, populism, remains a certain threat in Europe and across the world. Certainly, it is built on an illusion – a power play.

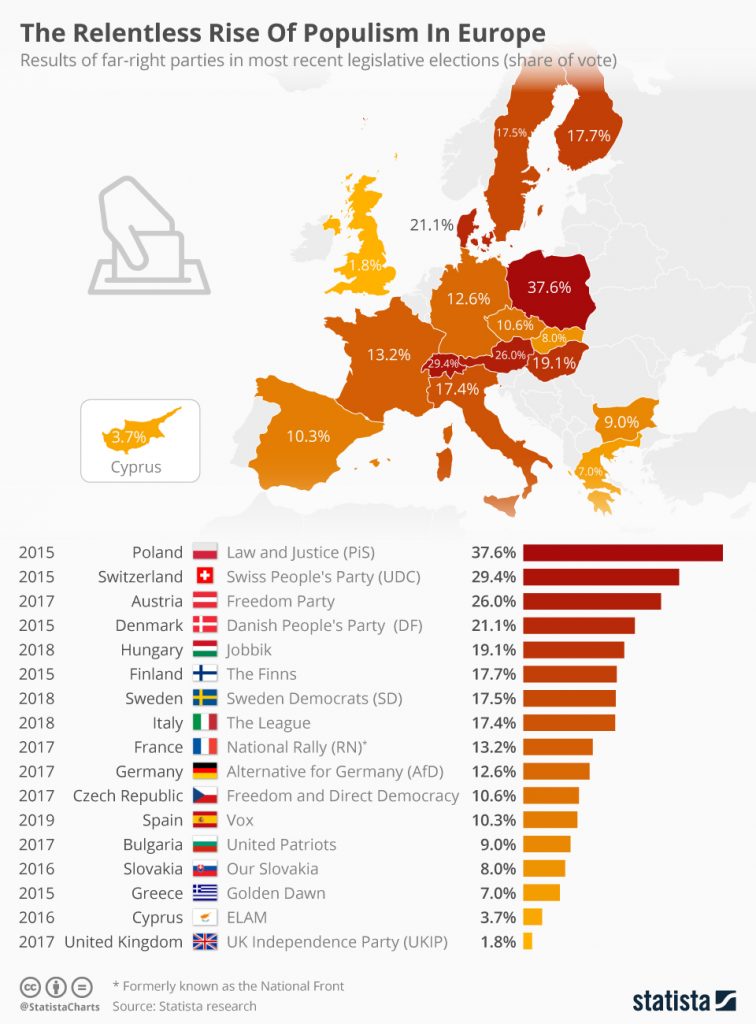

Figure 1, Statista 2019

Figure 1 explains that, so far as populism goes, the UK is the lowest. However, that is not to say it is sweeping Europe – certainly in authoritarian right-wing forms such as in Poland or Hungary. The UK is no excuse. We will delve into UK populism below.

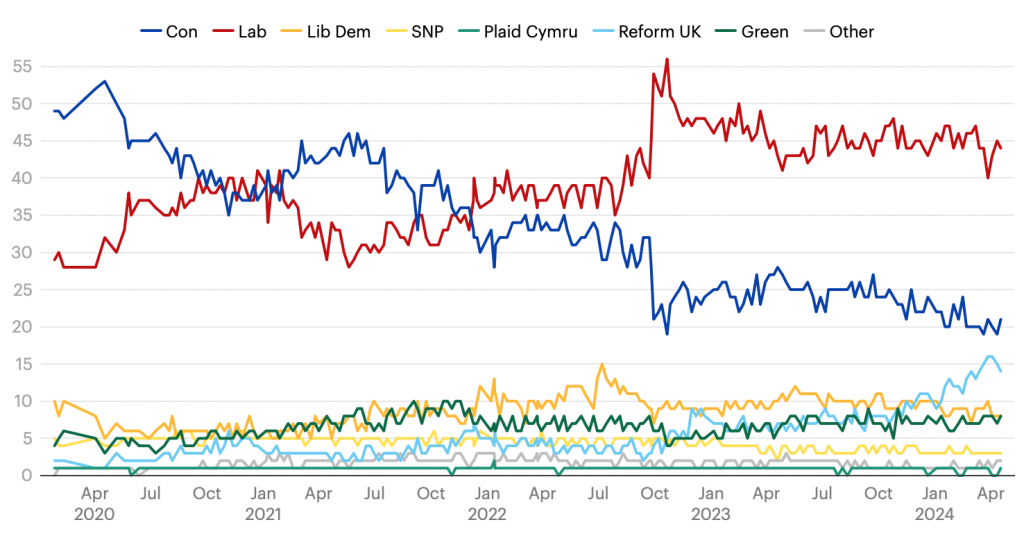

Figure 2, Westminster voting intentions, YouGov

Figure 2 explains the growth of Reform UK, a party that heavily uses populist rhetoric particularly on woke culture, net zero and immigration. Even before this party existed, this kind of rhetoric was exemplified by Nigel Farage and his UKIP party, using the disaffected voters concerned with ethnocentrism/immigration, and this went on to scare the Tory party under Cameron during the 2015 election (Ford & Sobolewska, 2020). Figure 2 shows concerning polling that Britain is becoming more polarised, between a more centrist labour but that Reform is growing and polling closer to the Conservative party, itself shifting right.

Brexit has been the eurosceptic force in Britain that has caused the rise of populism, Eurosceptics have mobilised this populist rhetoric into a national movement – using immigrants and the EU as ‘the other’ allowing for the growth of these parties and implementing a national ‘rage’ for some who are indeed susceptible to this populist rhetoric (Ford & Sobolewska, 2020; Clarke & Newman, 2017).

Since the Brexit referendum, and the resignations of David Cameron and Theresa May, Britain certainly took a turn from centrist politics to left- and right- wing populism (Foster & Feldman, 2021). From the fortnight since the Brexit referendum was held, hate crimes rose by 40% (Foster & Feldman, 2021), explaining the rise of right wing populism and hate that documents this politics and anger. It is indeed believe that this kind of hatred was not ‘defensive racism’, that may arise, for example, due to Islamist extremism but ‘celebratory’ (Foster & Feldman, 2021: 121), explaining that people are celebrating leaving the EU and the post-Brexit eurosceptic racism and anti-immigration.

Class has a rather odd relationship to this problem. It is often that radical right politicians, such a Trump, Farage, etc, who weaponise the working class votes in order to gain votes for their own populist gain. However, it has been studied that the working class votes that were involved in the Brexit referendum was insignificant, and that middle-class voters may have been more important in swinging the referendum (Mondon & Winter, 2019). This also speaks to the first paragraph, that populism is often caused by those who are actually members of the elites, and that it is an illusion. Mondon and Winter also conclude that focusing on this weaponisation of the working class as vulnerable to populism is a fair case, but that it also neglects elite driven racism and populism.

The growth of populism is difficult to counter – it is, ingenious and clandestine in the way it manifests – it brings a cult of personality that those who may be considered populist are ‘for the people’, when in reality, they simply are vying for power like any other. It is this cult of personality and rhetoric that polarises people and brings them into an emotive political space, which can be difficult to shake. The final reflection here, is that Britain may well be at a crossroads between a polarised society, and a more rational one.

References

Clarke, J. & Newman, J., 2017. ‘People in this courty have had enough of experts’: Brexit and the paradoxes of Populism. Critical Policy Studies, 11(1), pp. 101-116.

Covington, C., 2018. Populism and The Danger of Illusion. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 54(2), pp. 250-265.

Ford, R. & Sobolewska, M., 2020. Brexit and Britain’s Culture Wars. Political Insight, 11(1), pp. 4-7.

Foster, R. & Feldman, M., 2021. From ‘Brexhaustion’ to ‘Covidiots’: The United Kingdom and the Populist Future. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 17(2), pp. 116-127.

Mondon, A. & Winter, A., 2019. ‘Whiteness, Populism and the radicalisation of the working-class in the United Kingdom and the United States’. Indentities > Global Studies in Culture and Power, 26(5), pp. 510-528.

Mudde, C. & Kaltwasser, M., 2017. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. 1st ed. s.l.:OUP.

Statista, 2019. The Relentless Rise Of Populism In Europe. [Online]

Available at: https://www.statista.com/chart/17860/results-of-far-right-parties-in-the-most-recent-legislave-elections/

[Accessed 18 April 2019].

The author of this blog post highlights a very relevant topic in the UK today. The start of the blog post is well laid out as they explain what populism is and how it seems to be growing all across Europe. They then focus on how the Reform party seems to be growing in popularity. I would however make sure to include the title of the graph in the future just to make the point even clearer to the reader.

I especially found the idea of the illusion of populism and how many involved are actually quite well of or even part of the elite. This idea can especially be seen with people like Nigel Farage in the UK and Donald Trump in the US, both people with large amounts of money. Populism can also be seen not just in right-wing politics but also left-wing politics as people such as Jeremy Corbyn was view by some as a left-wing populist. However, in the UK the worry is more so that it is right-wing populism which is becoming more popular in the public. Especially, with the Conservative Party getting the Rwanda bill passed, the fear that populist views are spilling into everyday politics is very apparent. This blog post highlights why it may be becoming a more popular view.