Progressive or Performative? How FPTP Reinforces Under-Representation of Minorities

The United Kingdom’s (UK) voting system First Past The Post (FPTP), is a winner-takes all majoritarian voting system in which a candidate only needs to obtain a simple majority of the votes, to take away essentially all of the power in Parliament. Due to the fact that FPTP is not a proportional voting system, parties representing minority parties and also minority groups in society are often underrepresented by the way in which power is distributed. This is an ever-increasing problem as British citizens from minority backgrounds and members of the LGBTQ+ for example, are continuously increasing in numbers.

(Wingate, 2023)

A huge issue with FPTP is that women, people of colour and members of the LGBTQ+ are continuously underrepresented by the major parties and then when voting for smaller parties, the power is not distributed proportionately. Therefore, the voting system leaves voters with little choice and arguably increases voter apathy.

(Wikipedia Contributors, 2020)

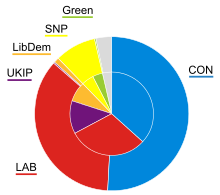

The diagram above is showing two different things. The inner circle is the popular vote, so the actual vote count from each voter at the election. Whereas the outer circle is how the power was distributed at the 2015 general election.

Incoming: The FPTP Snowball Effect – FPTP being an electoral system that favours major parties, often leads to an imbalance of minority voice, as smaller parties with niche platforms struggle to win seats. In turn, this means Parliament have less incentive to employ members of these minority groups into their workspace and politics in general. This leads to an underrepresentation and disproportion of demographics from society into the political scope. Finally, this leads to minority communities lacking change in decision making as their voices are not being heard. This can be an extremely damaging thing for politics as it can lead to a stagnancy.

There is also a geographical concern with FPTP because it can often dilute the impact of minority votes by only assigning 1 Member of Parliament (MP) to a constituency. For example, in the UK, if a minority group had a considerable backing in a particular constituency, but it did not quite reach the number of votes to be a majority, it would receive no power in that constituency. A real example of when this happened in the UK elections was during the 2019 election when the Green Party received over 850’000 votes yet only one seat in Parliament. This a disgrace to democracy and a completely outdated form of politics that must be dispelled immediately.

Moreover, MPs in recent times have attempted to silence the voters who want fair representation by placing performative minority representatives in Parliament. For example, Suella Braverman is a woman of colour and was arguably strategically placed into the Conservative Cabinet as a representative of women and people of colour, despite the fact she was undoubtedly unpopular according to the opinion polls. According to YouGov, 41% of the population actively dislike Suella Braverman, but yet her presence remains in Parliament – this is not democracy, this is performative activism.

What’s the Solution?

Proportional Representation –

Proportional Representation, more specifically the Additional Member System (AMS), is a system in which voters will have two things to vote for. A candidate to represent them and a party. Candidates will be sent out prior to the election for voters to gain opinions on and this way, more voters will see their candidates representing their parties, making voters feel more seen than in FPTP.

Using proportional representation means no vote has more value than another. Under FPTP, votes have different values. Here are some examples from the 2019 election (Ivorson, 2024):

- In the last election it took 26,000 votes for the SNP to win a seat compared with over 800,000 for the Green Party.

- Over 600,000 votes for the Brexit Party won absolutely nothing.

- Labour had to gain over 50,000 votes to elect each MP, while the Conservatives needed only 38,000.

With the use of a proportional representation system such as AMS, Parliament would feel obliged to put people of colour, women and members of the LGBTQ+ society forward and voters who feel strongly about these policies will have a place where their vote will be heard and decision making will follow.

Proportional Representation is not an unrealistic goal for the UK with this type of voting system being the most popular in the world. Arguably, FPTP is outdated with society and there has to be a relative change in political voting system.

In conclusion, FPTP continues to perpetuate systemic inequalities by marginalising smaller voices and favouring majority groups. Transitioning to a system of proportional representation system would offer a more equitable solution in the UK, to ensure a fair representation of all demographics.

The author discusses the proportion issues which arise from First past the Post and the uneven distribution of power which disadvantages minority groups in the United Kingdom. The role of smaller parties is underestimated as they typically focus on the interests of minority groups which in turn causes the minority groups to remain underrepresented which leads to these groups being side-lined by government. The author suggests installation of proportional representation as a means to resolve this issue. Overall, a great and interesting analysis.

The author provides a strong argument for proportional representation based on the under representation of small parties with the current first past the post system. However, there are examples of proportional representation that have led to less minority representation in elected bodies. For example, in the Scottish Parliament, which uses an additional member system, only 4.5% of the representatives are from an ethnic minority group. In comparison, in the House of Commons, 10% of the members are from ethnic minority groups. This comparison would indicate that there are other factors involved in the level of representation of minority groups in government. While the author makes a compelling argument that electoral systems affect the level of representation, it is necessary to consider alternative explanations or additional factors that may contribute to this trend.

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01156/