Northern Ireland: the volatile younger sibling of the devolved United Kingdom?

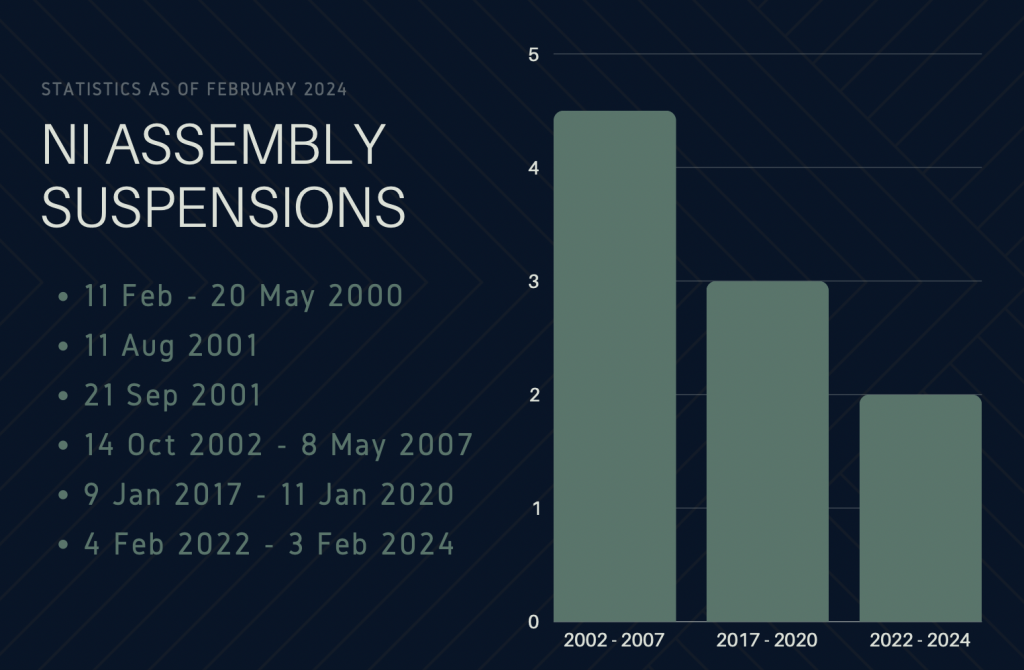

After just shy of two years, Northern Ireland’s devolved government has returned, but this return brings with it questions of the stability of government within Northern Ireland. The Northern Ireland Assembly and Northern Ireland Executive were formed in 1999, and have been amended in five agreements and suspended six separate times since then for a total time of almost ten years. Two of these suspensions came after ten years of uninterrupted power-sharing, which many believed would embed power-sharing fully, making collapse a much more remote possibility. Unfortunately, this proved not to be the case. This post aims to explore the institutions at hand to understand the underlying problems which cause Northern Ireland’s government to be so volatile and unstable.

Data: Torrance (2023), McCormack (2024)

Within the Northern Ireland Assembly, MLAs (Members of the Legislative Assembly) designate their community background as ‘unionist’, ‘nationalist’, or ‘other’. This allows for cross-community votes to take place on certain issues, ensuring a majority of the Assembly as well as a majority of unionist and nationalist MLAs vote in favour. However, as is immediately obvious, this excludes those who designate themselves as ‘other’, and arguably serves only to entrench and institutionalise the ‘culture war’ between unionists and nationalists; this leaves all policy positions to inevitably be viewed as one or the other, making progress that much more difficult. In turn, this limits the potential of small or more moderate parties, as those seen as more unionist or more nationalist are inevitably favoured by the public.

Image source: Gateley (2006)

The D’Hondt method ensures that all bigger parties receive ministries proportionate to their share of Assembly seats; the largest party gets first pick, then the next largest, and so on. This allows the Executive to reflect seat distribution within the Assembly, an important aspect of consociationalism (the system used in Northern Ireland, in which power is proportionally shared by rival cultures while allowing both necessary autonomy). While this is important, this mandatory coalition is arguably undemocratic due to having no formal coalition or alternating government. This formal coalition in combination with the aforementioned political ‘culture war’ means that there is a lack of co-operation between ministries, with politicians and parties being well-known to be extremely protective over their portfolios and refuse to work with other ministries, even on policy areas that require such collaboration. Understandably, this makes it much more difficult to bring bills into law.

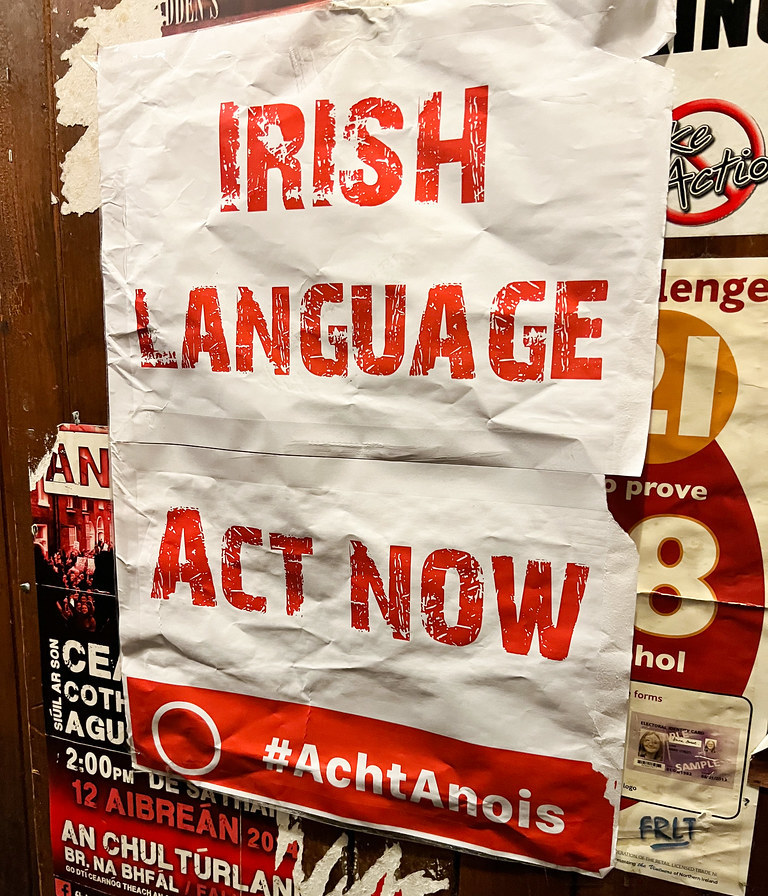

Image source: Quine (2022)

Bills are brought into law in the Northern Ireland Assembly much the same as in the UK Parliament, being introduced, debated, examined by a specialised committee, further debated, and finally voted on. Despite this fairly straightforward approach, many destabilising issues arise out of the creation and implementation of law, provoking political crises. Even when the Assembly and Executive are functioning as normal, the passage of law and progress are stalled by boycotts, walk-outs, and brinkmanship (the threat of violence or endangerment in order to gain an advantageous outcome). Minority veto rights also cause issues, allowing parties to essentially hold the Executive to ransom. Many long-term policy impasses cause frequent issues, such as the Irish Language Act, as do wider UK policies such as Brexit; Brexit affects Northern Ireland in particular as it is the only part of the UK to share a land border with the European Union. Here we also see another major issue brought about by the identification of policy position as being with one community or another: in the case of unexpected contentious issues, it means that the government lacks the strength to handle unanticipated challenges, as was the case with the Renewable Heating Initiative (which led to one of the most recent suspensions of the Assembly).

It seems clear that there is little appetite for compromise within the Northern Ireland Assembly, even if this means a years-long suspension. This raises many questions as to the commitment to devolution of larger parties, a worrying prospect in an already crumbling institution. While the Belfast / Good Friday Agreement (the agreement which brought peace to Northern Ireland and upon which its devolution was formed) brought an end to decades of conflict, it has also “reinstated this conflict as an organizing logic of governance in Northern Ireland” (p. 666). Without change, the Assembly and Executive will continue only to quasi-function as community divisions are continually deepened and progress struggles to be made.

References

Birrell, D. and Heenan, D. (2017) The Continuing Volatility of Devolution in Northern Ireland: The Shadow of Direct Rule. The Political Quarterly, 88(3) pp. 473-479. Available from https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12391 [accessed 8 February 2024].

Jenkins, S. (2024) Northern Ireland will leave the union, and Scotland could too. True devolution is the only way to save it. The Guardian, 2 February. Available from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/feb/02/cardiff-edinburgh-devolved-labour-leadership-union [accessed 6 February 2024].

Knox, C. (2015) Sharing power and fragmenting public services: complex government in Northern Ireland. Public Money & Management, 35(1) pp. 25-30. Available from https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2015.986861 [accessed 8 February 2024].

McCormack, J. (2024) NI’s government has returned Stormont – what you need to know. London, UK: BBC. Available from https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-67726389 [accessed 10 February 2024].

McCrudden, C., McGarry, J., O’Leary, B., and Schwartz, A. (2016) Why Northern Ireland’s Institutions Need Stability. Government and Opposition, 51(1) pp. 30-58. Available from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26349792 [accessed 8 February 2024].

Murphy, M. C. and Evershed, J. (2022) Contesting sovereignty and borders: Northern Ireland, devolution and the Union. Territory, Politics, Governance, 10(5) pp. 661-677. Available from https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1892518[accessed 8 February 2024].

Torrance, D. (2023) Devolution in Northern Ireland. London, UK: The Stationery Office. Available from https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8439/CBP-8439.pdf [accessed 8 February 2024].

Image Sources (Licensed under Creative Commons 2.0)

Gateley, L. (2006) DSC01766, Belfast Parliament, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/lyng883/245153987/in/album-72157594287026917/ [accessed 10 February 2024].

Quine, T. (2022) Irish Language Act Now. Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/quinet/52384575731/in/album-72177720299689261/ [accessed 11 February 2024].

This article discusses many interesting points surrounding devolution in the instance of Northern Ireland – and how its devolved government faces numerous issues that Scotland and Wales do not have to deal with on a daily basis. Of particular interest to me is how the author discusses that MLA’s must designate their community background as Unionist, Nationalist or Other and how this serves to continually determine how citizens vote and respond to certain people in power. It would be interesting to delve more into whether this is something that is still necessary in 2024 – or whether it is an outdated system that was more fitting to Northern Ireland 20 years ago. Many politicians within Northern Ireland view these identities as crucial to themselves and for the party they stand to represent, as well as the voters who engage. However, the fact that somebody who is designated as ‘other’ can never be First Minister for example, allows for these divisions to remain deeply rooted in our society. The First Minister role’s are designed to be ‘equal’ in which to allow one Unionist and one Nationalist, however there is still the standing that one is a Deputy. The opening of Stormont for the first time since 2020 has seen the first Nationalist First Minister for the country, as has been met with apprehensiveness from the Unionist community. In the opening speeches of the new First Minister and Deputy – there remained a focus on the backgrounds they come from. Generally the points made referred back to the troubles and how this has affected and led to their political positions. I would be curious to see whether this is something that allows for Stormont to be seen as a ‘tug of war’ between Nationalist and Unionist parties rather than a government for all in Northern Ireland with a focus on the everyday issues that affect citizens. Overall, this is a really interesting article which touches on many important factors that play into the complicated devolved governance in the country.

This article was particularly informative in discussing issues caused by the layout of the Northern Irish Assembly. As the blog writes Northern Ireland works under a consociationalism system, despite consociationalism being essential to maintain peace and stability in Northern Ireland by ensuring all major groups are represented in government, it is clear that it further entrenches the separation of the two communities, opposed to a government working for all. I found the implications of the system particularly interesting. As someone who was unfamiliar with the set-up of Stormont, this blog provided a clear outline of why no formal coalition having has allowed a serious lack of cooperation between ministries and causes significant delays in passing bills. Perhaps the blog could of gone further and provided some possible reforms or discussions surrounding the future of the NI assembly, possibly highlighting arguments of it being an outdated system.

The authors introduction includes interesting information regarding the boycotts of Stormont, and highlights a valid point that Northern Irelands government is unstable and volatile in comparison with the rest of its UK counterparts. Since devolution in 1999, the Executive has not been functioning for more than 40% of the time.

20220901-Pivotal-briefing-Governing-Northern-Ireland-without-an-Executive.pdf (pivotalppf.org)

The author also successfully highlights how due to MLAs having to designate their community backgrounds, policy positions often can be viewed as either unionist or nationalist, often overshadowing the actual issues being dealt with, something that is a very salient problem in Northern Irish politics.

The issue of competing interests of unionist vs nationalist, could perhaps explain why there has been an increase in voters for the more moderate parties as time has progressed. Since 1998, votes for the Alliance party as first preference have increased from 3.7% in 2003 to 13.5% in 2022, up 8 seats since 2017. The author also successfully highlights the issues of how there is a limiting potential for the more moderate parties like Alliance, as the NI institutions traditionally are biased towards nationalist/unionist parties.

The author provides a good description of how the D’Hondt method is used to appoint ministers. It is also important to note that the Minister of Justice is the only Northern Ireland Executive minister elected by cross-community vote. Policing and justice powers were not devolved until 2010, but when these powers were granted to the NI executive, the DUP did not want a Sinn Féin minister to be able to hold the post. It was then agreed that any justice minister would require a cross-community vote. This also displays the importance of the smaller more moderate parties, as Alliance has held the role of Justice Minister every year of devolution apart from 2016-2017. The leader of Alliance Naomi Long is the current holder of the post.

The author also puts forth valid opinions about the change required for the NI institutions. If the trends continue towards increased votes for the more moderate “other” parties, further changes will have to be made in a review of the NI institutions. Reviews of the NI institutions may more salient than ever in light of the most recent boycott of Stormont, as there has appeared to be an increasing disenfranchisement from the public with the NI institutions, with protests demanding that politicians end the boycott and “get back to work”, (Stormont: Protesters tell politicians to ‘get back to work’ – BBC News) displaying that there is an ever increasing pressure for change in NI as time goes on.

The author analyses the context of the formation and ongoing suspensions by providing a historical overview of the Northern Ireland Assembly in a straightforward read and remains concise to help maintain the attention of the reader. The author helps the reader by providing a supplementary graph showcasing the statistics on the historical and ongoing suspensions in Northern Ireland’s Assembly. Helping to emphasise the deep-rooted issues of the historical ‘culture war’ within the government. The author perfects the structure of analysis by following the historical context by delving into the mechanisms and electoral system set up to further entrench the ‘cultural war’. Which helps readers who are not from Northern Ireland become aware of the structural set up that upholds the divisions. The author uses nuanced policy impacts like Brexit and the Irish Language act that have progressed the long-standing ‘cultural war’ that affects the ongoing suspensions in the Northern Ireland Assembly. Adding depth by using real-world examples. The author’s post critically examines limitations of the current system maintaining an impartial view allowing for trust to transcend the post. The author also uses very relevant and up-to-date sources adding credibility to the author’s analysis, while demonstrating engagement with the ongoing situations within Northern Ireland. Overall, providing a very deep outline of the challenges that are ongoing within the state, however, the blog post would benefit by adding further analysis by highlighting possible areas for reform in the future.

This analysis provides a detailed examination of the challenges facing Northern Ireland’s devolved government, highlighting key institutional and political factors contributing to its instability.

The D’Hondt method for distributing ministries and the naming of MLAs are only two examples of the structural elements of the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive that are examined in detail. The research shed lights on how these institutional structures influence political dynamics and exacerbate governance issues by looking at them.

The piece points to several policy areas as points of difficulty for the devolved government, including Brexit and the Irish Language Act. The research illustrates how these policy disagreements worsen political tensions and impede the advancement of government by bringing attention to them.

Although the research highlights important obstacles, it may expand on its discussion by suggesting possible reforms or policy proposals. It would be more helpful to analyse governance challenges constructively and to encourage discussions of political remedies if specific recommendations were made, such as improving cross-community collaboration or changing the D’Hondt process.