Early morning yawn

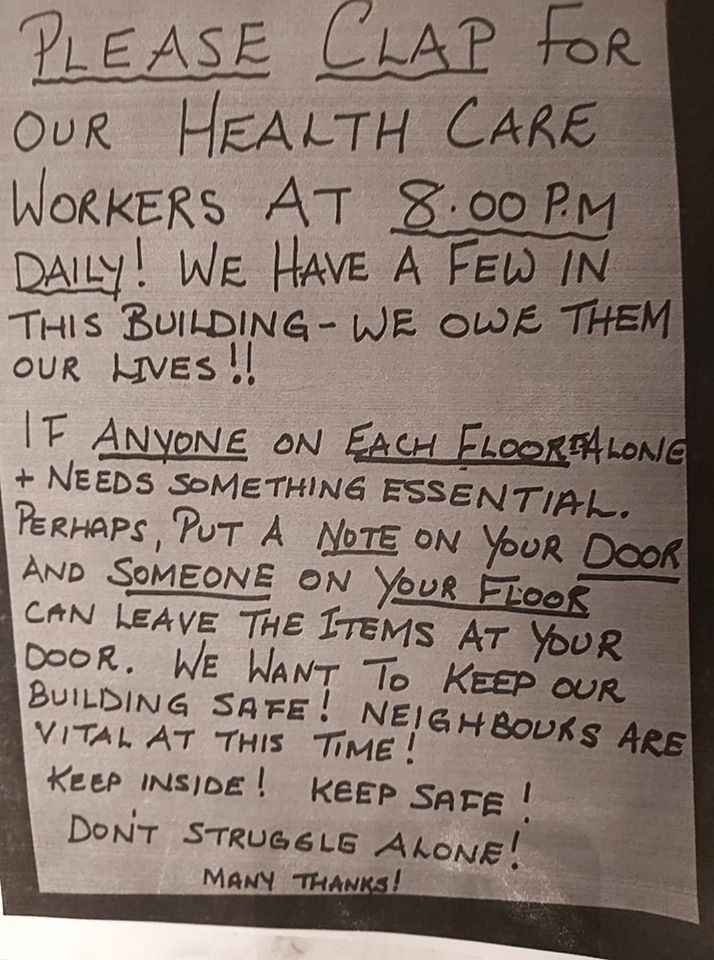

When was the last time you helped or were helped by a neighbour?

What does a rainbow mean to you?

I went to a Black Lives Matter protest and saw women in their late sixties protesting against police brutality, racial profiling, systematic abuse and mistreatment and I wondered how tiring and painful it must be for them as mothers and grandmothers to have to beg and protest just to be treated equality every day of their lives. I saw babies there no older than 1 or 2 and I wondered if they would have to spend their lives doing the same, filled with rage at how this was still happening, and then I went home.

I left with friends, planning on when we could meet up again, complaining about when we would ever return to “normality” after this pandemic, my anger shifting to the loss of holidays, nights out, and losing hours at work.

I went to the shop and bought snacks, holding my sign and then boarded a bus all while passing by police, vaguely aware of their presence, undisturbed by them.

At home, my mind already drifted onto online shopping, scrolling through fast fashion websites like Urban Outfitters and Pretty Little Thing with extreme right wing racist and trans-phobic CEOs, justifying abandoning my morals by clothing that was just too cute to not buy.

I listened to my friends’ excuses for not being involved, for not signing petitions, attending protests or speaking out, “I’m not really political” or “something came up” and I also listened to those who didn’t give any, brushing it off.

I listened to family members ‘slightly’ racist jokes, ignoring but not confronting them or my own innate ignorance and prejudice opinions.

I remembered how, as a child growing up in New York City, that if I was lost, I was instructed to go to the police, learning to see comfort in their presence at late nights alone and to cheer and praise my heroes for their work, angry at the few racist ‘bad apples’.

I listened to the news of the heightened charges against Derek Chauvin, now facing second degree murder, along with his colleagues now facing charges for accessory to murder, happy that justice was achieved, but then my phone lit up with the details of the murder of David McAtee, the African American man known for handing out free meals to police officers, shot by officers during these protests who had turned off their body cams, claiming to be only “returning fire”, whilst trying to protect his injured niece and other peaceful protesters rushing to take cover under the flurry of pepper balls and rubber bullets, his body lying in the street for 12 hours. Then I remembered all the names that hadn’t received justice, whose murders still walked free: Elijah McClain, Breonna Taylor, Toyin Salau, Eric Gardener, and all the names I didn’t remember and I wondered if we really achieved anything at all, if we were destined to continue to fight for the same things, five minutes, five days, years, centuries on, and why this was the case.

And then I realized how little I had actually done.

I realized how easy it was for me to shed my sign, to walk home, to walk to the store, to complain about the ‘new normal,’ an ‘invisible’ privilege people of colour never have. Their lives have never felt my ‘normal’ of being able to ignore the police presence, or breathe a sigh of relief for police who have never been their heroes but enemies, being no such thing as a ‘bad apple’ if each cop represents a systemically racist system, only being worse apples among a horrific bunch, of mindlessly consuming and supporting racist and trans-phobic leaders who for them don’t just have ‘different views’ but a view that seems them as sub-humans, views which could kill. I realized they couldn’t indulge in the luxury of not being political, because their lives were at stake if they didn’t, because they had to keep fighting to make sure that they retained any equality whilst I was handed mine.

I realized that my half-assed allyship of attending rallies against racism or posting for a few days isn’t enough and that the reason this keeps happening is because for me, this is a trending event one so easy for me to forget about and ignore if it becomes too much. But for people of colour, these events are an unforgettable reminder, every new victim serving as a harrowing example of who they could be, what they face.

I will never be in the same position as these victims, as my friends. I understand that I will never understand their pain or fear. My white skin is a shield from the brutality they face and that’s exactly why I must do better and use my enormous privilege to make change. To stand in solidarity with my peers of colour and amplify their voices and call out myself and my white peers’ ignorance. To risk cutting off friends, family and opportunities to stand against racism. To even risk not shopping at ‘trendy stores’ and to be consistently pushing for change for systematic racism inherent in every corner of our societies that have granted me my privilege, not just for a few minutes or hours but forever. Without doing so, these issues are destined to permanency.

Why study an MA in Irish Studies at Queen’s? Hear more about this unique interdisciplinary programme from academics and students.

What’s it like to study an MA in Public History at Queen’s? The course director, Dr Leonie Hannan, recently held a webinar on this unique programme. You can watch it below to find out more.

What’s it like to study an MA in Conflict Transformation and Social Justice at Queen’s? The course director, Dr Fiona Murphy, recently held a webinar on this unique programme. You can watch it below to find out more.

In this short video, political scientists at Queen’s University Belfast – Dr Muiris MacCarthaigh, Dr Elodie Fabre, Dr Andrew Thomson, and Dr Stefan Andreasson – share their perspectives on COVID-19’s impact on the study of politics.

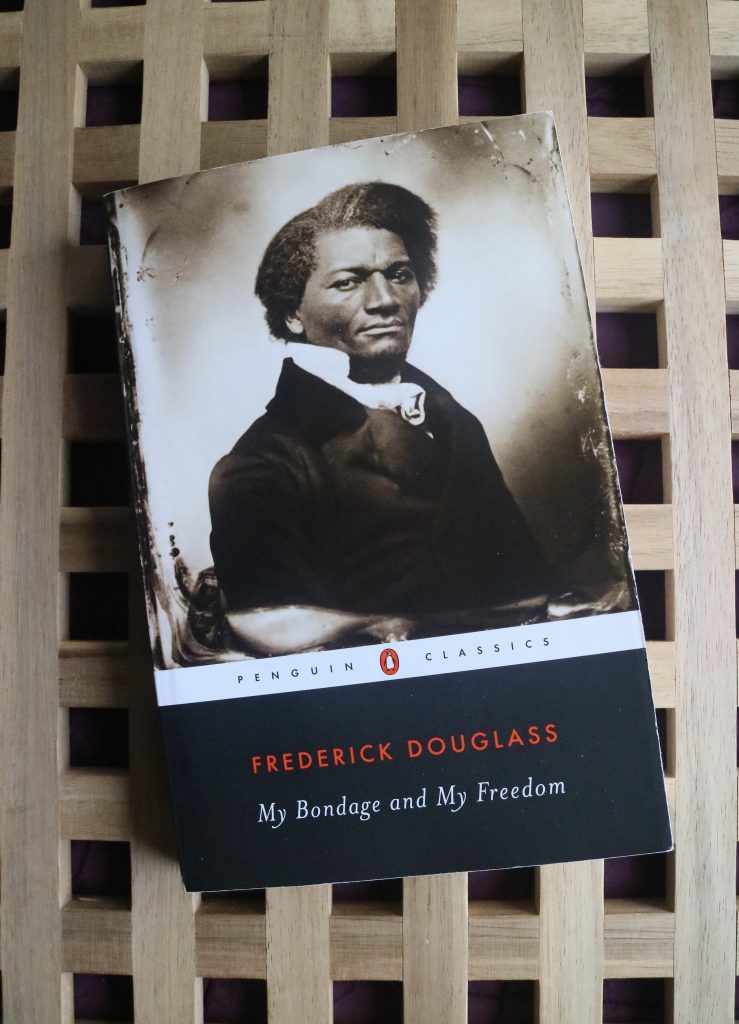

‘The first work of slavery is to mar and deface those characteristics of its victims which distinguish men from things, and persons from property’. These are the words of Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery in Maryland to become a leading campaigner for the abolition of slavery and for the rights of Black people. Besides his work as a public speaker, journalist and newspaper editor, Douglass also wrote a biography – publishing three versions of it in his lifetime – reflecting on his life in slavery and his subsequent emancipation, of which My Bondage and My Freedom was the second version.

I became interested in the experiences of figures like Douglass and his contemporary, Booker T. Washington, former slave and noted educationalist, when researching questions of recognition and respect. I was especially interested is the way in which people subject to the most extremely harsh and degrading treatment could nonetheless retain their self-respect in such conditions. While others were unable to resist the relentless humiliations heaped on them by their captors, some people nevertheless managed to hold onto their sense that they were entitled to be treated as equals. Primo Levi, writing about his own experiences in Auschwitz, distinguished these two groups as the drowned and the saved.

Douglass recounts the harshness of the slave life, both the physical hardship of work in the fields (which he himself largely escaped, as it happened) and the hunger and cold (which he did not). Beatings and whippings were a common feature of this life, whether for any of a host of minor infractions, or purely on a whim. One slave owner in Baltimore would strike out at her slaves as a matter of course, whenever they passed by. While other slave holders disapproved of this excessive behaviour, none, Douglass noted, would have questioned her right to beat her slaves.

The violence of slave life is amply represented in popular culture, from 12 Years a Slave to the cartoonish Django, but Douglass also emphasizes the way that slaves were denied a family life, not only denied the option of legal marriage, but regularly split up and sold to different parts of the country. Douglass was raised by his grandmother and scarcely met his own mother. He was surprised to find, on moving to the main plantation as a boy that he had brothers and sisters, although, unsurprisingly, they were never to become close. Sociologist, Orlando Patterson, described this as a sort of ‘social death’ experienced by slaves, whose relationships could be ended at any moment by their masters and who were compelled to live with this possibility hanging over their heads.

The essence of slavery, Douglass points out, does not lie in the harsh treatment to which slaves were regularly subjected, but rather in the status of being a slave. Douglass himself was fortunate enough to be sent away to the city rather than to the fields. There he managed to learn to read and write and life was comparatively comfortable. However, a ‘slaveholder, kind or cruel, is a slaveholder still‘ – it makes no difference to one’s slave status. To be dominated, i.e. in the power of a master, a dominus, is, in the words of political philosopher, Philip Pettit, to be exposed to the possibility of uncontrolled interference in one’s life. It is this persistent vulnerability to others who may mistreat you with impunity, that is central to domination rather than individual incidents of brutality. A kind master is preferable to a cruel one, but both have the same power over the slave and nothing compels them, if they happen to be kind, to remain so.

Living with this vulnerability can take a heavy toll on those concerned. This is not simply a matter of damaging one’s well-being, but of potentially warping one’s relation to oneself, diminishing one’s sense of self-worth and self-respect. Douglass reflects that slaves commonly adopted a servile attitude in the hope of deflecting the attention of the master. In time, however, servility can become a role from which one cannot escape. The ancient Stoic philosopher, Epictetus, himself a former slave, recommended reflecting on the transience of this life, not simply as an aid to enduring its hardships, but to enduring them with one’s dignity intact. Maintaining one’s dignity might sound like a rather rarified concern, but for Douglass, as for so many others, it was a matter of life and death. In the most dramatic passage of Douglass’ narrative, he recounts how he refused to accept a beating from an especially brutal overseer, even though in doing so he risked his life. Victorious in the struggle, Douglass says that, ‘I had reached the point at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact, while I remained a slave in form.’

Douglass always insisted, with good reason, that chattel slavery, in which one is legally nothing more than a piece of property, is the most intense form of domination. The end of the slave system which sustained these relationships, however, did not simply eliminate race-based domination. The end of slavery proper did not, as Douglass found, securely establish the equal status of black people. Securing people against domination is a complex matter, requiring the restructuring of laws, institutions, and social attitudes. Alongside more subtle and insidious forms of oppression and inequality, we continue to see the persistence of unusually intense forms of domination, as George Floyd’s recent death has shown yet again. The bare minimum that a decent society can provide is security against this sort of treatment and yet it appears that this still cannot be guaranteed, 155 years after slavery itself was abolished in the US.