By Ross Allinson, MA Student in Violence, Terrorism and Security

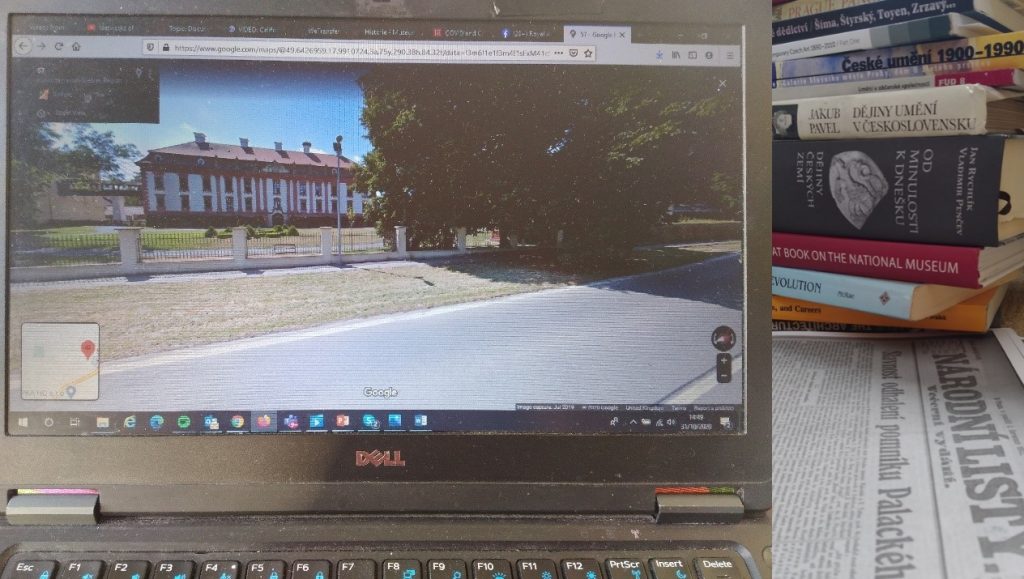

October and November are significant months in the German calendar. This year October 3rd marked the 30thanniversary of German Reunification (Deutsche Einheit); this November 9th, 31 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. This time of the year always gets me thinking about the lives of East Germans. As a 15-year-old who had been living in Germany for a year and half I finally got to go to the Hauptstadt of our Federal Republic in 2013. I was excited to see the Bundestag, Chancellor Merkel’s Office and Alexanderplatz. In my head the place I wanted to see most was the former Ministry of State Security’s (Stasi) Headquarters on Normannenstrasse, East Berlin.

This building was not only the headquarters of the East German intelligence agency; it was the place where Erich Mielke (The Minster) and his 91,000 strong work force, systematically shattered the lives of the enemies of socialism, including their own citizens. They called themselves the shield and sword of the party. The party being the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands). This party led the German Democratic Republic for 40 years.

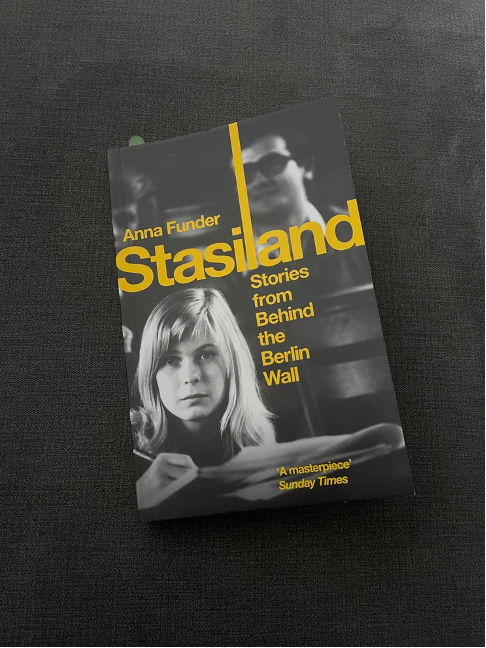

This Reading Week I decided to re-read an old favourite of mine: Stasiland – Stories from behind the Berlin Wall by Anna Funder.

It is a collection of tragic stories that were told to Funder during her time working in a reunified Berlin. Funder is an Australian author and investigates the lives of East Germans affected by the regime, and more specifically the Stasi. The book transports the reader to the centre of the oddities and cold systemic brutality of the regime in East Germany.

Funder gives voice to the stories of East Germans who dared to stand against the regime – some who didn’t even realise they were standing against it. Instead of going into the detail of the Stasi’s plans for the nation and their surveillance methods, Funder tells the human story, which is often lost in the discourse surrounding East Germany.

From the book we quickly discover that every East German has a story of some kind and the book gives us a glimpse into the new lives of the East Germans, who no longer have the republic that both repressed and hugged them at the same time. It exposes that German reunification was far from a perfect political goal; too many people were left vulnerable and left behind when the socialist republic began to draw its last breaths on 9th November 1989.

The book is a must-read for anyone interested in the human causalities of the socialist system and of the wounds that are only made deeper by the new reality in the ‘New’ Federal Republic of Germany. In 1986 ‘Deutschland ist grosser als die Bundesrepublik’ (Germany is bigger than the Federal Republic) was graffitied onto the Berlin Wall at Potsdamer Platz. After reading Stasiland you will see that this rings true even today.

If you want to know more about the German Democratic Republic, comment below and I will point you in the direction of some amazing podcasts, and resources.