GORDON RAMSEY

LECTURER IN ANTHROPOLOGY

07/05/2020

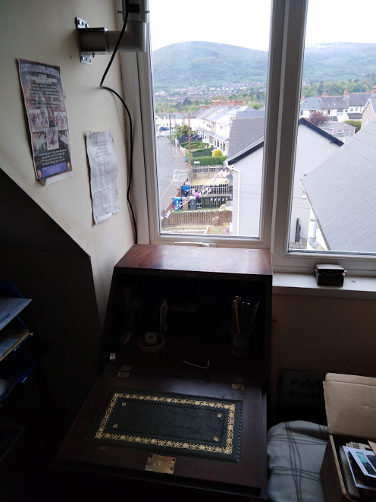

Thursday evening. Sitting at the desk in the small upstairs office which has been my workplace since Queen’s University was locked down, I see my north Belfast neighbours coming out of their houses to participate in the weekly applause for the NHS. I open the window and join in the applause. Many of the houses in the street have been decorated with bunting for this year’s VE Day commemoration, which has been widely publicised in the neighbourhood: two minutes silence at 11.00am; Churchill’s speech on TV at 3.00pm, “socially distant” family celebrations in front gardens at 4.00pm.

The thought of VE day turned my attention to an old cardboard box which has sat untouched on a shelf in the wee back room for at least ten years. I know it contains photographs of my mother’s wartime service as well as other family memories: I had meant to go through them any create albums, but had never found the time. I opened the box. It contained a jumble of photos and documents going back over a century. The first thing I pulled out, however, was my own military enlistment papers, dated August 1975. My mother must have kept them: I didn’t. A brochure for the Royal Anglian Regiment promises “good pay, excitement, comradeship, promotion and the opportunity to travel, drive, signal, learn other skills and further your education.” Looking back now, the army delivered on every one of those promises, but ironically, the same cannot be said for the society it was defending. I did indeed further my education, eventually going on to achieve a PhD, but in real terms, I was paid more as an eighteen year old infantry recruit in 1975 than I am now paid as a contracted university lecturer with 13 years of experience. I dug deeper into the box.

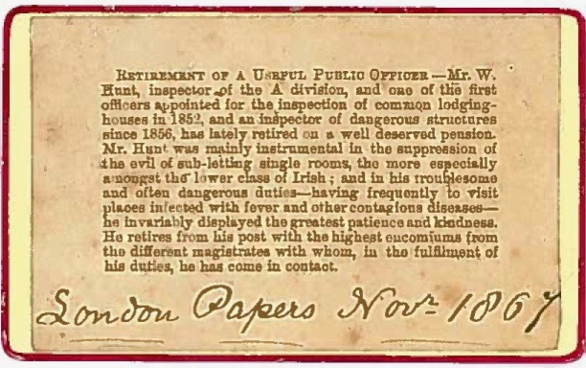

The oldest thing I found had immediate resonances with our current situation. It is a preserved newspaper clipping dated November 1867. It announces the retirement of my great-great-grandfather, William Hunt, from the Metropolitan Police, in which he served as the Inspector of Common Lodging Houses. Although he died long before I was born, I still have his truncheon and whistle, and the desk on which I am writing, a little battered now, but still beautiful, belonged to him.

The clipping says that “Mr. Hunt was mainly instrumental in the suppression of the evil of subletting single rooms, the more especially amongst the lower class of Irish; and in his troublesome and often dangerous duties – having frequently to visit places infected with fever and other contagious diseases – he invariably displayed the greatest patience and kindness.”

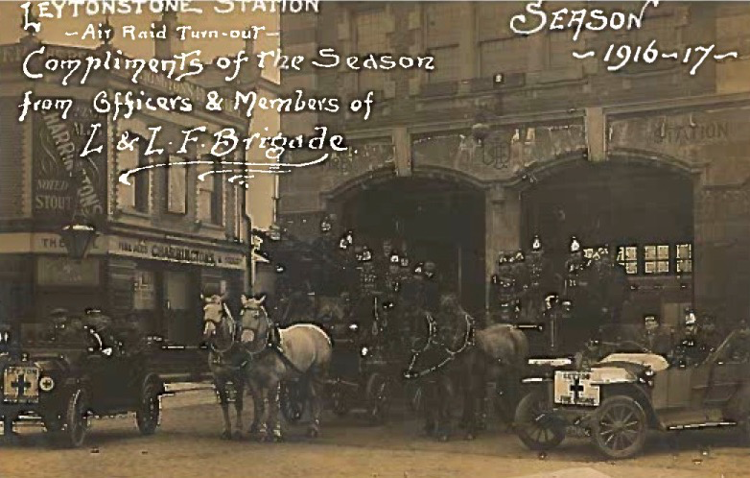

I am glad that my great-great-grandfather was kind. I wonder what he would have thought had he known his great-granddaughter, my mother, would marry one of the “lower class of Irish”? That was far in the future, but such class controversies entered the family in the next generation. In the cardboard box, I found a paper bag full of photographs and letters belonging to John Hunt, son of William Hunt, who had been the founder and Captain of a North London Fire Brigade.

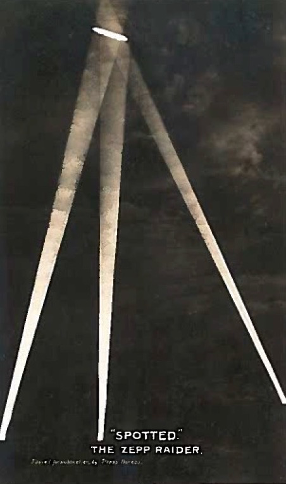

John had clearly been held in respect by his fire brigade comrades, but when he entered business after leaving the fire service, things went downhill. According to my mother, he not only lost all his own money, but married a rich heiress and lost all her money too. Nevertheless, he retained Diadora Lodge, the large family home with its extensive grounds in suburban North London, and he clearly retained his pride and class consciousness, for when his daughter, Ada, my grandmother, fell in love with Walter Larkin, a lowly carpenter, he refused to allow the marriage. When Walter was conscripted into the Royal Engineers during the Great War and posted to a searchlight unit in northern England, John hoped the romance was over. But the couple wrote to each other throughout the separation, and thirteen years after they first met, John finally relented and allowed the marriage. A postcard I found in the box reflected Walter’s wartime role.

My mother, Margaret, was born in 1917 and eventually, Ada and Walter inherited Diadora Lodge. I found photos of the house in the box too. Ada had to learn that shopping on a carpenter’s wage could not include ordering deliveries from Harrods, and Walter converted the large gardens, once a bourgeois playground, into extensive vegetable plots. I remember shelling peas and gathering walnuts there when I was a child, as well as playing in the wilder corners that remained uncultivated. I found a photo in the box, showing my grandad in his leather armchair with my sister on his lap, me in the arms of my grandmother, and my parents standing behind.

Now I came to the material that had first drawn me to the box. My mother, Margaret, had joined the RAF in 1941, largely to escape her over-protective mother. She had already lived through the Blitz, and was posted first to Wales, and then overseas to Egypt. A small autograph book I found in the box contained good wishes from her RAF friends, including this poem, dated June 1946, by her close friend, Marjorie:

There is sunshine here in Cairo,

Such as England rarely sees,

Though its fierce full heat is tempered

By the balmy winter breeze.

In the gardens at Gezira

Rose and antirhinnum smile

And the gleaming white fellucas

Sweep superbly down the Nile.

But I’d gladly give the river,

And the flowers and the sun,

For of shower of sleet,

In a London street,

Where the old red buses run.

My mother was demobbed from the RAF later that year, but she did not return to London for long, rather accompanying her closest airforce friend, Margaret Ramsey, back to her home in Ireland, where she met and married her best friend’s brother, my father, Bob Ramsey. My father had left school at fourteen and begun a seven year apprenticeship as a steam locomotive fitter. During the war, he moved to Short Brothers in Belfast, the city his mother was originally from. At Short’s, he maintained and repaired the aircraft which fought the Battle of the Atlantic. During the Belfast Blitz of 1941, nine members of his mother’s family were killed when a bomb struck the communal air-raid shelter in which they had taken shelter. When my father went to the house to check on them in the morning, he found the house intact and the dog, which was not allowed in the air-raid shelter, safe and sound, but the family gone. The box contained a photo of my father, with his workmates, their attention focused on something ahead of them. A union meeting? He was a committed member of the TGWU. A religious service? He was a Presbyterian but not an overly observant one. Or a football match? He played when he was young and always followed the game. It is one of the few photos I have of him without a cigarette hanging nonchalantly from the side of his mouth. Eventually, a combination of the cigarettes and locomotive boiler soot destroyed his lungs, and he died at the age of 63 – the same age I am now.

At the bottom of the box, I found a pamphlet which brought me back to VE Day. It was the order of service for a religious ceremony marking my mother’s departure from the RAF. The front cover, which showed two quotes from Churchill’s 1940 speeches, was headed, “Your Finest Hour”.

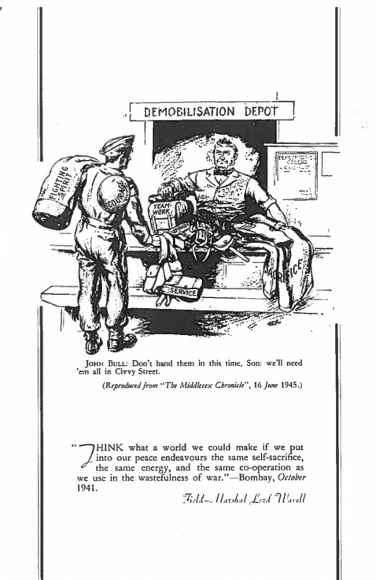

The back cover conveyed a message with a very different tone, including a cartoon, showing a soldier attempting to hand in his kit at the Demob Centre. The kitbags he carried are labeled, “Fighting Spirit”, “Service”, “Teamwork”, “Courage”, and “Sacrifice”. “Don’t hand them in this time, Son”, the storeman says to him: “We’ll need ‘em all in civvy street”.

Below the cartoon is another quote, this time from Field Marshall Wavell: “Think what a world we could make if we put into our peace endeavours the same self-sacrifice, the same energy, and the same cooperation as we use in the wastefulness of war”.

These were the word which accompanied every servicewoman and man when they returned to “civvy street”, and they are a reminder that my parents’ generation were not just the generation that defeated fascism: they were also determined to build a better, fairer and more humane society than the one which had led to the growth of fascism in the first place. Right at the centre of the society they built in the post-war years was the institution on which we all depend today: the National Health Service. Just like my parents’ generation in World War Two, NHS staff never wanted to be heroes. But this is their Finest Hour. And as we applaud them, we must remember that our task is not just to beat COVID-19, but to build a better society than the one which allowed us to become vulnerable to it in the first place. That is what true Victory means.