Dominic Bryan

Professor of Anthropology

22/05/2020

In Northern Ireland the Covid-19 lockdown started in the middle of March 2020 and by the 23rd we were officially social distancing. The fundamental reason for this strategy was to protect the National Health Service, the ‘front line’ for saving lives. At 8.00pm on 26th March people across the UK, most stuck in their homes, stepped out of their doors and leaned out of windows to acknowledge the NHS workers by clapping. This has been repeated every Thursday during the lockdown gaining widespread publicity. In addition, people have been displaying rainbows from windows also in support of the NHS.

For those of us studying anthropology, this immediate representation of our world through rituals, symbols and commemorations is not a surprise. People need to find ways of creating a sense of community, a sense of common activity, and doing so when restricted from the public sphere is an act of resistance as well as an affirmation of cohesion. And this has political ramifications.

We should not assume the meaning that participants are giving to these rituals. People have different reasons for participation. What I think can be suggested is the power of these events in terms of promoting cohesion in a neighbourhood and in support for the health service and the enhanced status given to its workers. The power of this apparent national consensus will play out in the politics that follows the lock down. The symbol of the rainbow has taken on new political meaning and this will be important.

The country was asked to observe a minute’s silence at 11.00am on 28th April for those key workers that have died. This was intended to coincide with International Workers’ Memorial Day on which people killed or injured at work are annually remembered. This commemoration was founded by trade unions in the US whilst in Canada, in 1984, a National Day of Mourning for workers was instituted. Since 2001 the United Nations has recognised it as The World Day for Safety and Health at Work. It is worth noting that whilst the Trade Union Congress cast this act of commemoration within this longer standing event this was lost in media coverage. I am willing to bet that British Prime minister, Boris Johnson, had not recognised this day in the past. But will he in the future?

The use of ‘11.00am’ and the minutes silence is also significant. In UK terms, it mimics the better know and better observed events on Remembrance or Armistice Day when a minute’s silence is also observed at 11.00am to remember those who lost their lives in the service of the military. We are of course well used to the way in which the monarchy and political elite line-up to be at the forefront of this event. But then this day is cast as of national remembrance enhanced by the idea that the conflicts the military serve in, are in all our interest: ‘The Died For Us’. This of course is not uncontested.

We might also note with concern that society sometimes appears better at commemorating the sacrifice of those who died in war than looking after those that ‘returned’. This would suggest that those in power find the act of commemoration easier (and cheaper) than the act of investing in the victims and survivors.

It is noticeable that this fits a common political discourse using war as a metaphor in dealing with the pandemic. As Costanza Musu has already cogently argued this war time imagery of the front line, soldiers, sacrifice, and an ‘army of workers’ (The Sun Newspaper) is compelling but also dangerous. It places the struggle within highly nationalistic tones marginalising the global nature of the problem. Already leaders around the world have attempted to depict it as an ‘invasion’ introduced by foreigners. It also casts those in caring and healing professions alongside the military.

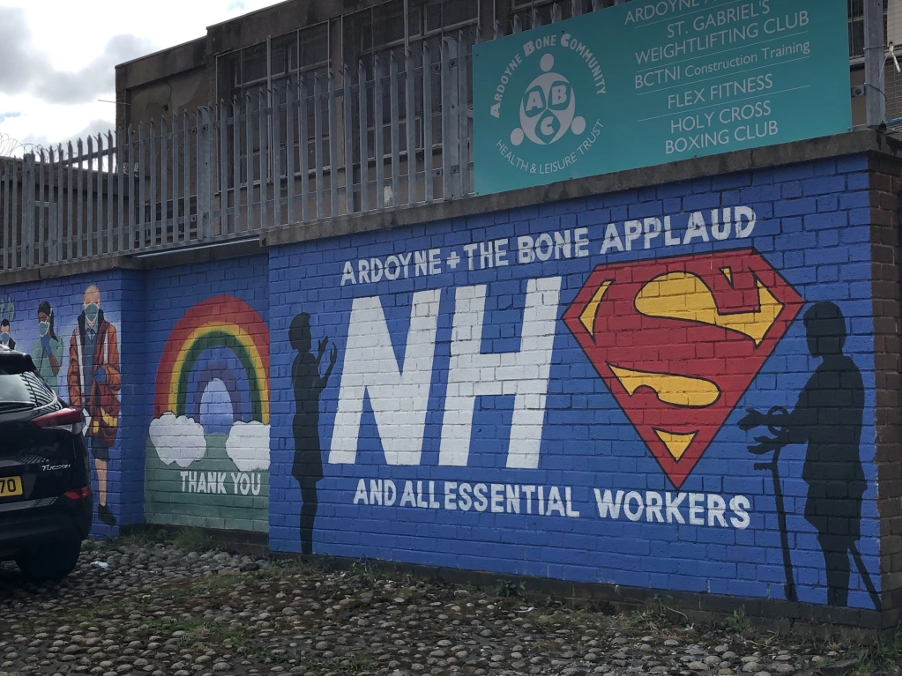

In Belfast there have been interesting local symbolic and ritual interpretations of the pandemic. There is evidence of common support for the institution of a public health service across the ethno-political boundaries that structure our society. As such, rainbows, which has become the symbol for supporting front-line workers, have appeared in windows across Belfast. The Thursday night doorstep clap has taken place regardless of the ethnic geography of the city. The NHS has been supported on murals on both sides of the ethno-political divide. Support for the NHS, popular with almost everyone, has been expressed in common public displays. Prior to March 2020 it was difficult to imagine a cause that could garner such universal backing.

Yet there are differences. The nationalistic approach to ‘combating’ the virus has been reflected in unionist areas of the city with the use of Union Jack flags, some with ‘Support the NHS’ and ‘Thank you to the NHS and all key workers’ written across them. Others have engaged with the militaristic analogy with banners saying ‘No Surrender to Covid-19’. The amazing exploits of 100 year old veteran, Tom Moore, who raised £30 million walking the length of his garden 100 times, was also depicted on a mural in Clonduff, East Belfast, along with his military medals and a rainbow (see above).

In Irish nationalist areas the narrative has been based on the rainbow and NHS staff as superheroes. Whilst I would not want to exaggerate these differences, as unionist areas have many representations that do not use the symbols of Britishness, there are nevertheless contrasts in commemorative symbols and narratives.

Why is this important? It is important because the financial and political implications of this, when the immediate crisis has past, will be enormous. The new symbolic status of the NHS and frontline workers will have a power that will be competed over by politicians. This will have massive ramifications for what gets publicly funded, and how. There is now competition with the military in the commemorative calendar. Consequently, who we depict as ‘defending’ the country will play out when government departments look at their budgets in years to come.